Key Points

-

Details the relative indications for a common space-gaining procedure increasingly used during adult orthodontics.

-

Highlights the pitfalls of inter-proximal reduction allied to diagnostic considerations and technical approaches promoting successful outcomes.

-

Presents and appraises a plethora of available armamentarium to carry out safe and precise inter-proximal reduction.

Abstract

Inter-proximal enamel reduction has gained increasing prominence in recent years being advocated to provide space for orthodontic alignment, to refine contact points and to potentially improve long-term stability. An array of techniques and products are available ranging from hand-held abrasive strips to handpiece mounted burs and discs. The indications for inter-proximal enamel reduction and the importance of formal space analysis, together with the various techniques and armamentarium which may be used to perform it safely in both the labial and buccal segments are outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inter-proximal reduction (IPR), reproximation, slenderisation or air-rotor stripping is an adjunctive orthodontic treatment procedure that may be used in both the labial and buccal segments to gain space.1,2In view of the current emphasis on non-extraction based orthodontics, alternative space-gaining procedures including arch expansion, non-compliance molar distalisation,3 such as the use of fixed mini implant-supported adjuncts, and preservation of the leeway space are increasingly being explored.4 Furthermore, IPR has gained increasing popularity due to the growing acceptance of adult orthodontics coupled with the difficulty associated with space closure in older patients, reticence of some patients to undergo extractions, the ability to create a more precise and appropriate amount of space in selected cases, and the risk of reopening of extraction spaces following appliance removal.

Inter-proximal reduction is typically indicated in the resolution of mild to moderate crowding (up to 8 mm),5 the correction of Bolton tooth size discrepancies,6 and in the enhancement of dental aesthetics. There is also limited evidence alluding to the potential for improved long-term stability with contact point reshaping.7,8,9IPR may be exploited in conjunction with fixed appliance therapy, although its application with removable appliance therapy such as proprietary clear aligners including Invisalign is commonplace.

The concept of IPR is based on the findings of Begg10 who studied aboriginal groups and noted an absence of dental crowding in combination with natural occlusal and interproximal wear attributed to non-refined abrasive diets. Subsequently, IPR was popularised by Sheridan1,11who described its potential remit as an alternative to extraction or expansion in selected cases. This paper aims to outline considerations underpinning safe and effective IPR as well as highlighting the various techniques and armamentarium available.

General principles

While the use of inter-proximal reduction has become more widespread, clearly acceptable oral hygiene, absence of dental disease, and lack of previous proximal reduction are prerequisites. IPR is typically undertaken in adult patients rather than adolescents as the contact points tend to be more accessible and adequate gingival retraction and visualisation of contacts is more difficult in adolescents. Moreover, poorly performed IPR can produce irreversible enamel furrows, scratches and ledges, predisposing to plaque retention. There is also a risk of sensitivity if the underlying dentine is exposed. The production of a smooth enamel surface and sparing excessive removal of enamel are therefore imperatives. Long-term evidence, however, suggests that IPR is safe with no increased risk of caries or periodontal disease ten years subsequent to IPR with diamond disks.12 Similar findings have been reported following air-rotor stripping in the buccal segments up to six years later.13,14

Considerations during planning

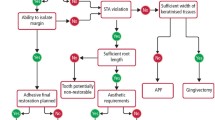

A thorough space analysis should be carried out to calculate the exact amount of space required. A decision as to whether sufficient space may be generated with IPR in order to achieve treatment objectives is essential. Moreover, IPR does carry demonstrable albeit limited associated risk. As such it should only be planned when necessary. Accepted formal approaches to space planning are recommended in order to select the appropriate mode of space creation.15,16,17

Enamel thickness

Before deciding how much enamel can be safely removed, an appreciation of the volume of available enamel is important. In general, enamel is slightly thicker in the region of the contact point and gradually decreases towards the cemento-enamel junction. It appears that the amount of enamel is unaffected by gender18 although there is some racial variation.19

In the lower labial segment, enamel is slightly thicker on the distal surfaces, with thicker enamel on both surfaces of the lateral incisors (Table 1).19 Similarly, in the anterior region the enamel is slightly thicker on the distal surfaces of both the lateral and central incisors, with a mean difference of 0.1 mm.20 In the lower buccal segments, enamel is also significantly thicker on the distal surfaces, with the second molars having thicker enamel than the premolars by the order of 0.3–0.4 mm.18

It has been widely suggested that up to 50% of proximal enamel can be removed by IPR without any deleterious effects.1,12,21Tuverson22 recommends removal of 0.3 mm on each lower incisor proximal surface and 0.4 mm on the canine proximal surfaces. However, Sheridan23 suggests 0.25 mm reduction of enamel in the anterior region and a more radical 0.8 mm on each proximal surface of the posterior teeth resulting in a potential space gain of almost 9 mm. The magnitude of possible IPR is also affected by the amount of pre-existing interproximal wear. Although standardised radiographs may be useful in quantifying the amount of enamel present, these should be used with caution as they risk overestimating the amount of enamel present.24

Contact point location

In general, contact points are rounded and are more occlusal in the anterior region and become more apical posteriorly. The process of enamel reduction flattens the contact area leading to apical movement of the contact point. It is suggested that the interproximal contact remains 4.5 to 5 mm from the upper border of the alveolar crest to ensure that 'black triangles' are not visible.25 In a healthy periodontium, the alveolar crest is 1.5–2 mm apical to the cemento-enamel junction. It is important to restore the normal anatomy of the contact point and area following reduction. An apical contact point may be physically difficult to reduce; apical relocation of the contact point may also impinge on the biological width of the periodontium.

Mesio-distal tip

Ideally, mesio-distal tip should be corrected before carrying out IPR in order to allow even enamel reduction across the contact point. In addition, reduction should be carried out perpendicular to the interdental papillae to avoid introducing a tipped appearance to the teeth.

Shape and size of teeth

Bennett26 described three main incisor crown shapes (Fig. 1) – rectangular, triangular and barrel shaped, although there is not necessarily a correlation between tooth shape and enamel thickness. Rectangular teeth have broad contact points with no visible spaces. Triangular teeth commonly have incisal contact points with visible 'black triangles' (Fig. 2). Due to the shape of these teeth, even minimal enamel reduction can generate significant space within the arch. Barrel shaped teeth tend to have contact points in the middle of the tooth with apparent space at the incisal edges. Enamel reduction may approximate the incisal edges, but may relocate the contact point apically. The size of teeth must also be considered as microdont teeth, for example, peg laterals, may not be amenable to IPR whereas anatomically larger teeth may have more favourable morphology (Fig. 3).

Rotations

The presence of rotations may preclude adequate access to reduce the interproximal enamel evenly. Therefore, enamel reduction may need to be carried out in stages as it may be necessary to align the teeth first. If the contact point of a tooth is completely excluded then it can be reduced prior to alignment depending on its accessibility.

Restorations

The presence of restorations poses a number of considerations for IPR. In particular, the contact point anatomy may have been altered when the restoration was placed and thus may need replacement following reduction. However, the presence of large interproximal restorations may facilitate larger increments of IPR and therefore more space gain.

Procedure

Armamentarium

Numerous materials are available to perform IPR. These approaches encompass two main categories: manual or mechanical. When deciding on the preferred armamentarium, patient safety is paramount in ensuring adequate protection of the soft tissues and prevention of overheating of tooth tissue. Some of the more recognised commercially available IPR armamentarium are outlined in Table 2. Each has unique advantages, disadvantages and relative indications.

Inter-proximal strips

Hand-held abrasive strips are manufactured in different sizes and varying grit. They allow easy access to the interproximal area and can also be used for finishing or recontouring of proximal surfaces. The strips can be hand-held or mounted on a handle. Access can be challenging in the posterior region, they are time-consuming to use, and can lead to discomfort. They can be useful in removing enamel very sparingly with increasing grades permitting progressive increase in the magnitude of enamel removal. The strips are available colour-coded with varying widths and grits. They can be single or double-sided to allow selection of specific surfaces for reduction.

Rotary discs

Rotary diamond discs can effectively facilitate IPR and may be less time-consuming to use compared to hand strips. As is the case with hand strips, they are available in various thicknesses and grits. They require mounting on a handpiece and should be used with a safety guard to protect the soft tissues. Anterior segment contact points are more accessible compared to posterior segments where access to allow use of discs can be technically more difficult.

Oscillating strips

Oscillating strips or discs are quick to use and allow for precise enamel reduction (Fig. 6). The segmented disc systems promote enhanced visualisation and access when compared to 360 degree rotary discs. They are also handpiece-mounted, are available in various widths and are colour-coded. They can be single or double-sided, offering control of specific contact point reduction. IPR using this technique should be carried out incrementally, progressing through increasing widths to the desired amount rather than selecting the thickest width first. This modality is particularly useful in the anterior segments due to ease of access. Care must be taken to avoid excessive pressure, as this will risk fracture of the strip and ledging of the enamel surface.

This was undertaken with oscillating mounted strips with increasing widths (Fig. 5c). Smooth interproximal surfaces are produced without ledges. The finger-rest position ensures maximum stability and control

Burs

Chudasama and Sheridan5 advocate the use of safe-tipped air-rotor stripping (STARS) burs which have non-cutting areas designed to prevent notching of proximal walls whilst removing a precise amount of enamel. It does, however, require subsequent finishing with fine rotary discs or hand-held strips (Fig. 7).

Many of the modalities discussed are commercially available in kits and some use autoclavable components affording re-use. When performing IPR a conservative approach with sequential removal of the desired amount of enamel is recommended. Finishing with extra fine grit materials to produce smooth surfaces is also advisable; this is essential to prevent plaque accumulation and demineralisation. Dental floss can be used to confirm smooth surfaces are present occluso-gingivally. During the procedure the magnitude of enamel removed can be gauged incrementally using bespoke gauges (Fig. 5f) or orthodontic wires of known dimensions. These may also serve a dual purpose of protecting the underlying soft tissues during mechanical removal of the enamel. Enamel reduction procedures generate frictional heat28 which may have an adverse effect on the pulp. A critical temperature rise of 5.5 °C has been shown to cause pulpal irritation.29 Therefore, air or water-cooling is imperative during mechanical IPR and may require the assistance of a nurse.

Conclusion

IPR is a valid treatment modality as part of comprehensive orthodontic treatment. It has gained popularity in view of the increasing trend towards non-extraction based treatment and the increasingly popularity of adult orthodontics. As with any orthodontic procedure, case selection is paramount and the selection of IPR over and above other space-generating procedures should be informed by formal space planning and thorough planning in relation to the final occlusal and facial treatment objectives. A varied armamentarium is available to facilitate safe and precise IPR.

References

Sheridan J J . Air-rotor stripping. J Clin Orthod 1985; 19: 43–59.

Rossouw P E, Tortorella A . Enamel reduction procedures in orthodontic treatment. J Can Dent Assoc 2003; 69: 378–383.

Sugawara J, Daimaruya T, Umemori M et al. Distal movement of mandibular molars in adult patients with the skeletal anchorage system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004; 125: 130–138.

Brennan M M, Gianelly A A . The use of the lingual arch in the mixed dentition to resolve incisor crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 117: 81–85.

Chudasama D, Sheridan J J . Guidelines for contemporary air-rotor stripping. J Clin Orthod. 2007; 41: 315–320.

Bolton W A . Disharmony in tooth size and its relationship to the analysis and treatment of malocclusion. Angle Orthod 1958; 28: 113–130.

Boese L R . Fiberotomy and reproximation without lower retention, nine years in retrospect: part I. Angle Orthod 1980; 50: 88–97.

Boese L R . Fiberotomy and reproximation without lower retention, nine years in retrospect: part II. Angle Orthod 1980; 50: 169–178.

Aasen T O, Espeland L . An approach to maintain orthodontic alignment of lower incisors without the use of retainers. Eur J Orthod 2005; 27: 209–214.

Begg P R . Stone age man's dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1954; 40: 517–531.

Sheridan J J . Air-rotor stripping update. J Clin Orthod 1987; 21: 781–787.

Zachrisson B U, Nyøygaard L, Mobarak K . Dental health assessed more than 10 years after interproximal enamel reduction of mandibular anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 131: 162–169.

Crain G, Sheridan J J . Susceptibility to caries and periodontal disease after posterior air-rotor stripping. J Clin Orthod 1990; 24: 84–85.

Jarjoura K, Gagnon G, Nielberg L . Caries risk after interproximal reduction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006; 130: 26–30.

Kirschen RH, O'Higgins E A, Lee R T . The Royal London Space Planning: an integration of space analysis and treatment planning: Part II: The effect of other treatment procedures on space. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 118: 456–461.

Kirschen RH, O'higgins EA, Lee R T . The Royal London Space Planning: an integration of space analysis and treatment planning: Part I: Assessing the space required to meet treatment objectives. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 118: 448–455.

Fleming P S, Springate S D, Chate R A . Myths and realities in orthodontics. Br Dent J 2015; 218: 105–110.

Stroud J L, English J, Buschang P H . Enamel thickness of the posterior dentition: its implications for nonextraction treatment. Angle Orthod 1998; 68: 141–146.

Hall N E, Lindauer S J, Tüfekçi E et al. Predictors of variation in mandibular incisor enamel thickness. J Am Dent Assoc 2007; 138: 809–815.

Harris E F, Hicks J D . A Radiographic assessment of enamel thickness in human maxillary incisors. Arch Oral Biol 1998; 43: 825–831.

Pinheiro M . Interproximal enamel reduction. World J Orthod 2002; 3: 223–232.

Tuverson D L . Anterior interocclusal relations. Part I. Am J Orthod 1980; 78: 361–370.

Sheridan J J, Ledoux P M . Air-rotor stripping and proximal sealants. An SEM evaluation. J Clin Orthod 1989; 23: 790–794.

Grine F E, Stevens N J, Jungers W L . An evaluation of dental radiograph accuracy in the measurement of enamel thickness. Arch Oral Biol 2001; 46: 17–1125.

Tarnow D P, Magner A W, Fletcher P . The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. J Periodontol 1992; 63: 995–996.

Bennett J C . The future of clinical orthodontics: importance of incisor crown form and size. In Carels C, Willems G (editors) The future of orthodontics. pp 213–224 Belgium: Leuven University Press, 1998.

El-Mangoury N H, Moussa M M, Mostafa Y A, Girgis A S . In-vivo remineralization after air-rotor stripping. J Clin Orthod 1991; 25: 75–78.

Baysal A, Uysal T, Usumez S . Temperature rise in the pulp chamber during different stripping procedures. Angle Orthod 2007; 77: 478–482.

Zach L, Cohen G . Pulp response to externally applied heat. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1965; 19: 515–530.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pindoria, J., Fleming, P. & Sharma, P. Inter-proximal enamel reduction in contemporary orthodontics. Br Dent J 221, 757–763 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.945

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.945

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of interproximal reduction in individual teeth, and full arch assessment in clear aligner therapy: digital planning versus 3D model analysis after reduction

Progress in Orthodontics (2022)

-

Enamel interproximal reduction during treatment with clear aligners: digital planning versus OrthoCAD analysis

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

The rationale for orthodontic retention: piecing together the jigsaw

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Accuracy of interproximal enamel reduction during clear aligner treatment

Progress in Orthodontics (2020)