Key Points

-

Suggests that science can tell us much, but literature sometimes gives a deeper understanding.

-

Proposes that dentists 'do' a lot, but may ignore the effect of their treatment on the patient as a whole.

-

Uses the work of two modern English writers to highlight these issues.

Abstract

The heavily restored, failing dentition, often associated with older patients, is one of the clinical challenges of our time. Patients tend to have high hopes for definitive, comfortable solutions and dentists may struggle to meet those expectations. In his autobiographical work, Experience, Martin Amis describes his failing dentition and its emotional consequences. His reflections have much to teach us as a profession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Like father...

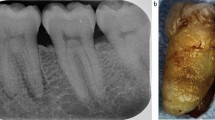

Kingsley Amis was a twentieth century English novelist, perhaps best known for his first novel, Lucky Jim, a humourous and satirical story of the academic life. He later won the Booker prize with his novel The Old Devils.1 In this, he describes the travails of Malcolm, who is retired and dentally at least, typical of his generation, with a heavily restored dentition (multiple crowns and a denture, of varying shades and contour) and periodontal disease (loose teeth). Despite much past treatment, Malcolm still fears both extractions and the consequent future inevitability of the bland whiteness of complete dentures ('snappers'). The snappers would come 'some day, but not now.' Inserting his current denture 'was always a tense moment; bending his knees and moving them in and out seemed to help.'

Kingsley Amis himself had been a 'tooth sufferer all his life,' according to his son,2 the author Martin Amis. The fictional Malcolm perhaps represents a little of the father's dental history.

Like son...

Martin Amis believes that he inherited his 'wreck' of a mouth from both his parents and his dental problems began young at the hands of (one of his many) dentists, a projectile poker chip and the elbow of his brother. In his autobiographical work Experience,2 he describes at length and in detail, his decades of dental travail and treatment.

He begins with the shame he felt at the poor appearance of his own teeth. In 1974, in his twenties, he describes how 'he hadn't smiled unreservedly for at least five years.' He feels at home in Spain, where many outwardly beautiful faces would smile to reveal 'a bag of mixed nuts, or more typically in Andalucia, a bag of mixed nuts and raisins.' Clearly Malcolm's 'colour atlas' of crowns would be an improvement on that situation. Later, Amis enviously admires one girlfriend's dentition for its 'prettiness' and describes another's 'crystal battlements.' Unsurprisingly, there appear to be no publicly available photographs of a young, smiling Martin Amis.

Appearance was not his only difficulty. Function was also a problem. On one weekend he recalls that eating was particularly difficult. Each time his top teeth met the lowers, he experienced 'a kind of electrical repulsion that made my head jolt.' He explains that his teeth always 'just felt wrong' because 'when I clenched my teeth, they didn't fit' and he experienced a 'resilient twang' every time they did meet. The mouth, he says, is 'uniquely vulnerable to obsession [...] if there's anything going wrong in there, then that's where you live: in your mouth.' It is possible, he seems to be saying, to disassociate oneself from stomach ache or a sore knee, in a way that is not possible with oral dysfunction.

Pain was another of Amis's problems. He describes sleepless nights, followed by spectacular swelling, leading to 'penny farthing nostrils [...] the right side of my face was telling the left side of my face what it would look like when it was very fat.' Few of our patients would be able to match the pain history he recites, being 'an expert on the musicianship of toothaches,' using, metaphorically, all the sections of a symphony orchestra, playing 'staccato, glissando, accelerando, prestissimo, and above all fortissimo.' Toothache is not only represented by classical music though. It can do 'rock, blues and soul [...] doo-wop and bebop [...] heavy metal, rap, punk and funk' and above it all, 'the tragic keening of the castrato.'

It wasn't for want of treatment that Amis's teeth eventually fail. Fifteen years on a hygiene regime that meant that he had 'used up something like eight thousand hours cleaning my teeth: the picks, of wood and water, the interproximal, the floss, the electric brush.'

However, after a five year period of non-attendance in his forties his condition was reaching a climax of need. He has a 'bridge which extends from ear to ear,' retained 'only by habit.' He could only chew on 8% of his mouth, he says. Yet when it is suggested that he should go to see a dentist, he prevaricates, an echo of Malcolm's 'not now.' I'll finish the novel, he says, then I'll get into the chair.

Eventually, as he considers his treatment (which appears to be initially an upper clearance and immediate denture) in New York, he returns to the idea of living in your mouth. As he contemplates the dental appointment, very nervously and apparently coping with Valium, coffee and cigarettes, he says he will be 'saying goodbye to myself. I would be different hereafter.' How different, he didn't know. But he would be 'different: a changed proposition.' You can almost hear the raised heart rate and fear in the tense, staccato phrases. Post-treatment, with the first look in the mirror, having been used to the convexities of his face, he expects to see concavities and maybe the 'squidgy compression of an Albert Steptoe.' Instead he sees 'a darkness, a void, a tunnel that leads all the way to my extinction.' He also believes that no teeth means no love – the inheritance of the keening castrato. He would have to sign up for an 'amatory crisis centre, where we would all sit around in a fug of peppermints and fixatives, with various mouthfuls of pottery clacking like castanets...'

The immediate denture, however, brings hope of a future life and future lives – a 'ticket to good looks and fine dining, to the head thrown back in vivid laughter, to nuzzling and honeying, to goopy kisses.' The reality, inevitably, is different – taste has gone, waterfalls of saliva have arrived, both eating and smoking he found extremely difficult, gagging was a problem, as was swearing. He goes to a bookshop to enquire for the astronomy section and is sent to astrology.

The denture he names 'The Clamp'. Never quite owning it as part of himself, it sits, not in his mouth, but in the clichéd glass, confronting him 'with its snarl or sneer.' The necessary purchase of Steradent reminds him of his youth and the embarrassment of buying condoms for the first time, a moment of 'potent arrival' and initiation. The equally embarrassing need for denture cleanser signifies, he says, the onward movement of time into old age.

Eventually, after further scans and scares, further surgery with 'irrigator, vacuum cleaner and two pairs of hands in my mouth, all at the same time ...' and some bone grafting to his lower jaw, Martin Amis concludes his dental saga. Presumably, implants followed at some point but he chooses not to describe anything restorative. In later photographs, he still does not smile.

Sixty pages – 15% of the book – are given to these dental traumas at the hands of dentists – hands Amis later describes as warm, strong, 'aromatic' and having a 'godly cleanliness.' In a book primarily telling of his relationship with his father, it becomes a volume about loss and separation – the death of his father, loss of his friendship with Julian Barnes, the murder of his niece (a victim of mass murderer Fred West), the death of his brother-in-law from AIDS, his father's divorce and separations and his own divorce. In giving so much emphasis to his dental traumas and tragedies, Amis powerfully equates his tooth loss with the grief of separation and death.

Like dentists...

Dental research confirms that patients who struggle to accept the loss of their teeth are less likely to enjoy eating and more likely to have difficulties forming close relationships.3 But, however much science can inform us, there can be few better personal descriptions of the traumas of oral pain, tooth loss and the discomforts of treatment than Martin Amis's Experience.2

Amis's memoir tells us that, as dentists: we do teach patients how to use floss and interdental brushes; we can pick up a handpiece and provide some restorative dentistry when prevention fails; we can use those warm, strong hands to manipulate luxators, elevators and forceps to extract teeth when the restorations fail; we can fill trays and mouths with sodium alginate in order construct acrylic replacements; we can insert bone and titanium and build pretty, porcelain battlements.

However, I believe Amis unintentionally reminds us that as a profession, hour by hour, week by busy week, we care for people: people with past hopes and present fears; people concerned about lost youth and approaching old age; people who worry about a loss of love and the end of life; people who have both immediate needs and a 'not now'; people who will have current expectations and later disappointments; people, like Malcolm, who need the reassurance that it is perfectly all right to jiggle their knees in and out when inserting their dentures.

References

Amis K . The Old Devils. London: Vintage, 2004.

Amis M . Experience. London: Vintage, 2001.

Davis D M, Fiske J, Scott B, Radford D R . The emotional effects of tooth loss in a group of partially dentate people: a quantitative study. Euro J Prosthodontics Restor Dent 2001, 2: 53–57.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hellyer, P. Experiencing the failing dentition: what dentists do. Br Dent J 220, 479–480 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.335

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.335