Key Points

-

Highlights the judicial use of antibiotics to minimise bacterial resistance.

-

Demonstrates the increasing awareness of appropriateness of prescribing.

-

Stresses the increase in awareness of prescription accuracy.

-

Shows the value in governance activities in improving patient care.

Abstract

Background Odontogenic infections are frequently treated with antimicrobials. The inappropriate use of these medications has led to bacterial resistance and the development of species which are resistant to the antimicrobials currently available. This has serious implications for global public health.

Aim A multicycle clinical audit was carried out to compare the prescribing practices of three paediatric dental departments in the North of England.

Results Results revealed deficiencies in prescribing practices in all three centres. Following education and the provision of an aide-memoire in subsequent cycles, improvements were seen in appropriateness of prescribing, increasing from 28% in the first cycle, to 71% in the third cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Odontogenic infections are a frequent presentation in clinical dental practice, with antimicrobials often prescribed to manage these infections. Antimicrobials account for the vast majority of medicines prescribed by dentists, and, in the UK, dental prescriptions account for 7% of all community prescriptions of antimicrobials.1 A survey of over 6,000 general dental practitioners in the UK revealed that 40% of dentists were prescribing antimicrobials on at least three occasions every week, with 15% of practitioners prescribing antimicrobials on a daily basis.2 Although effective at treating many infections, common side-effects exist and range from gastrointestinal upset to fatal anaphylactic shock.3 It is estimated that approximately one-third of all outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in the US are unnecessary4 with a similar situation being reported in the UK.5 A disturbing consequence of the over-use of these medications is bacterial resistance to the drugs that once eliminated them, allergy and reduced effectiveness, creating a risk to public health.

There are several sources of guidance that can aid appropriate and accurate prescribing. The Faculty of General Dental Practitioners has published guidance for use of antibiotics in the UK for adult dental patients.6 No UK guidance is available regarding the treatment of children, however; the American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (AAPD)7 has produced guidance for use of antimicrobials in paediatric dental patients. These recommend that they should only be provided under the following circumstances:

-

Acute facial swelling of dental origin

-

Dental trauma

-

The management of oral wounds contaminated with extrinsic bacteria

-

Paediatric periodontal disease (for example, neutropenias, Papillon-Lefevre syndrome, leucocyte adhesion deficiency).

To ensure appropriate dispensing of drugs, prescriptions should contain clear and accurate information regarding dose, frequency and duration. The British National Formulary (BNF) provides advice relating to the completion of prescriptions (Table 1).8

Finally, the Department of Health's Delivering Better Oral Health document recommends that children should receive sugar-free medicines where possible to reduce caries-risk.9

The aim of this audit was to evaluate the prescribing practices in three dental hospitals and evaluate improvements following educational interventions. The specific objectives were to identify which antibiotics were prescribed, assess appropriate use of antibiotic therapy in paediatric dental patients and to assess prescription accuracy.

A standard was set that all prescriptions issued should be in accordance with the AAPD clinical guidelines, BNF recommendations, and should stipulate 'sugar-free' where these were not routinely dispensed.

Method

Approval for the project was gained from the relevant Clinical Effectiveness Units. A retrospective case-note evaluation of 30 patients who were issued with a prescription from each centre was carried out over an eight month period. The first cycle was carried out from February to August 2009, cycle two from February to August 2010 and the final cycle from February to August 2012. Figure 1 highlights the stages involved in this multicentre audit.

Data was collected using a data collection sheet which was piloted on five patients in Sheffield in February 2009. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel 2007.

Results

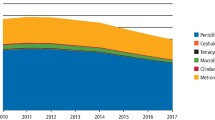

In the first cycle of this multicentre audit, 90 paediatric dental patients were identified, of which 89 were issued with a prescription for an antibiotic. One prescription was dispensed for an antiviral preparation and was excluded from further analysis. The most commonly prescribed antibiotic was amoxicillin (72%) of which 64 scripts were issued, followed by 13 scripts for metronidizole (15%), seven for a combination of amoxicillin and metronidizole (8%), three for phenoxymethylpenicillin (3%) and two for erythromycin (2%). The second and third cycle of the audit revealed similar results with small variation between the three centres.

The total number of prescriptions dispensed over the same time period in the third cycle had declined from 89 prescriptions in the first cycle to 68 in the third cycle, with 30, 22 and 16 prescriptions available from Liverpool, Manchester and Sheffield, respectively, over the same period, demonstrating a significant decline in the numbers of prescriptions being issued.

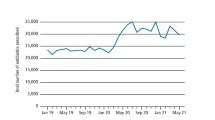

Appropriate prescribing

Of the prescriptions issued, only 25 scripts were deemed appropriate (28%) in the first cycle. These included 17 scripts for diffuse swelling (19%) and six for management of an open wound (7%). In the second audit cycle 46 prescriptions (51%) were given in accordance with the AAPD guidelines. A further improvement was noted in the third cycle with 48 (71%) appropriate prescriptions issued. A statistically significant improvement in the number of appropriate prescriptions was found between each of the cycles (p<0.05). Local swelling was the most common reason for prescriptions to be issued inappropriately in 23 (26%) cases in cycle 1, 10 (11.1%) instances in cycle 2 and 8 (12%) cases in cycle 3. Pain or pulpitis accounted for five (6%), seven (8%) and three (4%) in cycles 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Two (2%) prescriptions were issued as the patient was going on holiday in cycle 2 only. The proportion of prescriptions issued inappropriately in each cycle is shown in Figure 2.

Prescription accuracy

A total of 29 (43%) prescriptions contained errors in the third cycle. This was not statistically significantly different to the first two cycles (p >0.05), with 45 (51%) and 49 (54%) prescriptions completed inaccurately in cycles 1 and 2 respectively. Omission of the quantity of the drug (that is, stating the number of tablets or volume of liquid to be prescribed) was the most common error, accounting for 23 (26%), 30 (33%) and 14 (21%) in cycles 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The maximum number of errors per prescription was five in cycle 1, two in cycle 2 and three in cycle 3. Of the scripts highlighted in the third cycle, ten (15%) contained two or more errors which were consistent with previous cycles. One prescription was not signed (1%), seven (10%) did not state the duration, 14 (20%) did not stipulate quantity, two scripts had an incorrect dose (3%) and one script was not dated (1%) in the final cycle. These findings were similar to those found in the first two cycles (Table 2).

Sugar-free prescriptions

As Manchester Dental Hospital routinely dispenses sugar-free elixirs, only prescriptions from Sheffield and Liverpool were analysed for the omission of 'sugar-free'. This was not specified in 28 (47%) prescriptions in the first cycle but significantly improved over the audit cycle to 13 (28%) prescriptions in the last cycle.

Action plan

Between each of the three cycles an action plan was formulated (Fig. 1). Following the first cycle the results were disseminated at a regional audit meeting by the lead author and educational sessions were given in each of the three centres by the audit lead in each of the units. These sessions included presentation of the findings and reiteration of the BNF and AAPD guidance. Following the second cycle, the results were again disseminated to each of the three centres and an aide memoire was produced to be attached to the prescription pad in each unit (Fig. 3). After completion of the third cycle, the guidance from the AAPD and BNF were summarised and distributed with induction materials along with the aide-memoire. It is hoped this will ensure that all staff have received the appropriate guidance.

Discussion

Improvements were noted in prescription accuracy and appropriateness over the three cycles of this audit, however, these were not as great as expected and our standards were not reached. After each cycle, deficiencies were highlighted locally and collectively, findings were discussed and disseminated at local and regional audit meetings and action plans put into effect. These included an educational session and the provision of an aide-memoire attached to the prescription pad (Fig. 3), which aimed to encourage staff to reflect while prescribing and inclusion of current guidance in induction packs. Between cycles, there was a time lapse of several months, where staff may have forgotten their 'educational input' and relapsed into their old ways. A Cochrane systematic review concluded that feedback is more effective when provided more than once and is given in both written and verbal format, which may account for the decrease in prescription accuracy and appropriateness seen in cycle 2 and the subsequent improvement in cycle 3.10

The most common antibiotic prescribed was amoxicillin with nine scripts (13.2%) issued for a combination of amoxicillin and metronidizole. Amoxicillin has been reported to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic in general dental practice, followed by metronidazole and a combination of amoxilcillin and metronidizole.11 Accurate diagnosis and local measures in combination with narrow spectrum antimicrobials minimise disturbance to commensal flora. Costelloe and colleagues12 recommend that the fewest number of antibiotic courses should be prescribed for the shortest period possible and to avoid the use of more powerful broad spectrum antimicrobials wherever possible. Studies in medicine have shown that, when clinicians were more judicious and selective in prescribing for patients with urinary tract infections, a reduced incidence of resistant strains was observed.2 This same beneficial effect would be seen if dentists modified their prescribing behaviours.

Only 28% of prescriptions issued in the first cycle were deemed clinically appropriate. This has improved significantly to 51.5% in the third cycle. The most common reasons for inappropriate prescribing were 'local swelling', 'pain', and 'failed anaesthesia'. There is no evidence to support the use of antibiotics in these situations.13 Similar findings were reported by Chate and colleagues14 in their audit of GDP's, where only 29% of prescriptions were issued appropriately; however, this improved to 49% following an educational session for those involved. Another audit by Palmer and co-workers15 also found significant improvements in appropriate prescribing following an educational input. Realising the need for better prescribing practices, NHS Education for Scotland25 has recently launched an educational toolkit (ScRAP) to help prescribers reduce unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics. An on-line course is provided in association with a structured DVD presentation with all key clinical evidence, as well as gathering data for the individual practitioner. The results allow practitioners to compare their own prescribing decisions with local guidance and support areas for quality improvement. A randomised controlled trial26 is also currently being conducted in NHS General Dental Practices in Scotland assessing prescriber behaviours and compliance with current guidance to reduce antibiotic prescription. These results will be available early next year.

Anecdotally, the general public have become accustomed to receiving an antibiotic for any medical condition; clinicians may feel pressured to prescribe these. The expectation of patients is such that antibiotics are routinely dispensed for reasons such as 'going on holiday' and 'pain', which occurred in 2.2% and 17.6% of cases in the second cycle of this audit. A recent publication by McNulty and Francis16 suggests that patients should receive clear information, ideally reinforced with leaflets, about the likely duration of symptoms, self-care and the likely benefits and harms of antibiotics. However, it remains a challenge, to raise public and professional awareness on the risks of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and the long term implications of their misuse.

Approximately 43% of prescriptions in this audit contained errors, with almost 15% containing two or more errors. Unfortunately, there was no significant improvement in prescription accuracy over the three cycles of the audit. Failure to stipulate 'sugar-free' was the most common inaccuracy in the first cycle. It is important to stipulate this to prevent the prescription of cariogenic medicines when others are available. This promotes a culture of sugar-free prescribing to benefit those on long-term medications. This is supported by the Department of Health's 'Delivering Better Oral Health'9 which contains information regarding sugar-free medicines for children. However, this guidance may be contrary to current medical thinking. A recent paper by Sundar17 suggests that sugar in medicines makes them palatable and that bitter solutions inevitably affect compliance with prescribed treatment. However, it may be that if sugar-free medications are administered early in a child's life or given at mealtimes, this will surely improve compliance rates and palatability. It is essential that doctors and dentists take the lead by prescribing sugar-free preparations wherever possible.18

Other omissions over all cycles included date, signature, quantity and frequency with inaccuracies in dosage also noted. This finding is consistent with earlier studies also highlighting deficiencies in frequency and dose.14,15 They state that this is of major concern as antibiotics should be prescribed at the correct frequency, dose and duration so that the minimum inhibitory concentration is exceeded, and side effects and the selection of resistant bacteria are prevented. Previous studies reported improvements in this aspect in successive audit cycles; however despite the introduction of an aide memoire (Fig. 3) in all three departments in the second cycle of this audit, no significant improvement was noted. This is difficult to explain, given the educational input was targeted specifically to include discussion of the most common errors. However, as the most common error, with the exception of omission of 'sugar-free', was that of quantity, it may be that prescribers have omitted to state the volume or number of tablets required if they have already stipulated the dosage and duration of treatment.

New developments in health-care innovations present a constant promise of more effective patient experiences and outcomes. Although the dental profession advocates the importance of evidence-based dental disease prevention and treatment, the success in transferring research findings have been slow.19,20 Research from general medical practice also highlights similar difficulties. As a consequence, many patients do not receive appropriate care, or receive unnecessary or harmful care.23 While many studies offer solutions, inertia still exists. Recognised barriers to adopting new findings include lack of interest, lack of involvement, lack of time, lack of remuneration, and inadequate training.11,21 Traditional approaches to improve uptake of research findings such as reviews in clinical journals, clinical guidelines, access to electronic sources of information, continuing medical education courses and conferences have improved access and availability of current guidance, however its impact is limited. A systematic review of current literature by Grol and Grimshaw23 into the effectiveness of different approaches into changing professional behaviour, found that educational interventions (training sessions, newsletters, classes, and videos) seemed to have only a short-term effect; reminders (posters, coloured signs, labels with messages, patients reminding staff) have a modest but sustained effect; performance feedback (personal and non-personalised, oral and written) can improve practice, but the effect stops if feedback is not continued. In contrast, multifaceted interventions, with programmes combining, for instance, education, written materials, feedback, and reminders had a pronounced and sustained effect. They conclude that no specific interventions are superior for all changes in all situations. This view is also supported by a systematic review by Murthy and co-workers24 who also conclude that a multifaceted intervention is required to improve professional uptake of available evidence among health care providers and policy makers, however, there is insufficient evidence to support this approach. It also should be considered that inertia to change may not only come from the professional viewpoint but other agencies such as the patient, healthcare organisations, resources, leadership and the political environment. Despite these obstacles, it should be remembered that governing bodies require health professionals to keep abreast of the latest evidence-based guidelines and apply these to their everyday clinical practice to ensure patients receive the best care possible.22

Conclusion

This audit demonstrated significant improvements in appropriate prescribing and inappropriate use following an educational input and a substantial decline in the number of prescriptions issued over the audit cycles. However, this multicycle, multicentre audit highlighted deficiencies in prescribing in all three departments. Accuracy of prescribing and the judicial use of antibiotics are important to minimise bacterial resistance and to ensure patient safety. These results compare well with previous studies carried out in dental practice and ongoing education will be provided to ensure continued improvements are made in this aspect of patient care.

References

Sweeney L C, Dave J, Chambers P A, Heritage J . Antibiotic resistance in general practice-a cause for concern? J Antimicrob Chemother 2004; 53: 567–576.

Lewis M A . Why we must reduce dental prescriptions of antibiotics. European Union antibiotic awareness day. Br Dent J. 2008; 205: 537–538.

Dar-Odeh N S, Abu-Hammad O A, Al-Omiri M K, Khraisat A S, Shehabi A A . Antibiotic prescribing practices by dentists: a review. Therap Clin Risk Manag 2010; 6: 301–306.

Swift J Q, Gulden W S . Antibiotic therapy-managing odontogenic infections. Dent Clin N Am. 2002; 46: 623–633.

Dailey Y M, Martin M V . Are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency treatment? Br Dent J 2001; 191: 391–393.

Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (UK). Adult antimicrobial prescribing in primary care for general dental practitioners. Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (UK). London: Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2006.

American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry. Guidelines on the use of antibiotic therapy for paediatric dental patients. 2001. Revised 2009. Online information available at http://www.aapd.org/assets/1/7/G_Antibiotictherapy.pdf (accessed November 2014).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary: Prescription writing. http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current/guidance-on-prescribing/prescription-writing (accessed June 2015)

Department of Health/British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2009. Online information available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100810041346/http://dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_102982.pdf (accessed November 2014).

Freemantle N, Harvey EL, Wolf F et al. Printed educational material: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2007; 2: CD000172.

Palmer N O A, Martin M V, Pealing R, Ireland R S . An analysis of antibiotic prescriptions from general dental practitioners in England. J. Antimicrob Chemother 2000; 46: 1033–1035.

Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay A D . Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 2010; 340: c2096.

Fedorowicz Z, Keenan J V, Farman A G, Newton T . Antibiotic use for irreversible pulpitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2: CD004969.

Chate R A C, White S, Hale L et al. The impact of clinical audit on antibiotic prescribing in general practice. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 635–641.

Palmer N A O, Dailey Y M, Martin M V . Can audit improve antibiotic prescribing in general practice. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 253–255.

McNulty C A, Francis N A . Optimising antibiotic prescribing in primary care settings in the UK: findings of a BSAC multi-disciplinary workshop 2009. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65: 2278–2284.

Sundar S . Sugar-free medicines are counterproductive. Br Dent J. 2012; 213: 207–208.

Mackie I C . Children's dental health and medicines that contain sugar. Br Dent J 1995; 311: 141–142.

Clarkson J E . Getting research into clinical practice-barriers and solutions. Caries Res 2004; 38: 321–324.

Clarkson J E, Turner S, Grimshaw J M et al. Changing clinicians' behaviour: a randomized controlled trial of fees and education. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 640–644.

Rindal D B, Rush W A, Boyle R G . Clinical Inertia in dentistry: a review of the phenomenon. J Contemp Dental Pract 2008; 9: 113–121.

Kao R T . The challenges of transferring evidence-based dentistry into practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2006; 6: 125–128.

Grol R, Grimshaw J . From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patient's care. Lancet 2003; 362: 1225–1230.

Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke M J et al. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policy makers and clinicians. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2012; 9: CD009401.

NHS Education for Scotland. Scottish reduction in antimicrobial prescribing (ScRAP) programme. 2013. Online information available at http://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-discipline/pharmacy/about-nes-pharmacy/educational-resources/resources-by-topic/infectious-diseases/antibiotics/scottish-reduction-in-antimicrobial-prescribing-(scrap)-programme.aspx (accessed November 2014).

NHS Education for Scotland. Reducing antibiotic prescribing in dentistry (RAPiD). 2014. Online information available at www.sdpbrn.org.uk/index.aspx?o=3376 (accessed November 2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yesudian, G., Gilchrist, F., Bebb, K. et al. A multicentre, multicycle audit of the prescribing practices of three paediatric dental departments in the North of England. Br Dent J 218, 681–685 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.440

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.440

This article is cited by

-

Why do they do it? A grounded theory study of the use of low-value care among primary health care physicians

Implementation Science (2020)

-

Antimicrobial prescribing by dentists in Wales, UK: findings of the first cycle of a clinical audit

British Dental Journal (2016)