Key Points

-

The first double blind randomised controlled trial of transmucosal midazolam premedication in children undergoing a short ambulatory general anaesthesic (GA) for dental extractions.

-

The findings do not support the routine introduction of premedication of this dose of midazolam for children undergoing GA extraction.

-

Highlights the poor postoperative dental attendance record in this patient cohort.

Abstract

Background The project aims were to evaluate the benefit of transmucosal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg pre-medication on anxiety, induction behaviour and psychological morbidity in children undergoing general anaesthesia (GA) extractions.

Method One hundred and seventy-nine children aged 5–10 years (mean 6.53 years) participated in this randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ninety children had midazolam placed in the buccal pouch. Dental anxiety was recorded preoperatively and 48 hours later using a child reported MCDAS-FIS scale. Behaviour at anaesthetic induction was recorded and psychological morbidity was scored by the parent using the Rutter Scale preoperatively and again one week later. Subsequent dental attendance was recorded at one, three and six months after GA.

Results While levels of dental anxiety did not reduce overall, the most anxious patients demonstrated a reduction in anxiety after receiving midazolam premedication (p = 0.01). Neither induction behaviour nor psychological morbidity improved. Irrespective of group, parents reported less hyperactive (p = 0.002) and more pro-social behaviour (p = 0.002) after the procedure; older children improved most (p = 0.048). Post-GA dental attendance was poor and unaffected by premedication.

Conclusion 0.2 mg/kg buccal midazolam provided some evidence for reducing anxiety in the most dentally anxious patients. However, induction behaviour, psychological morbidity and subsequent dental attendance were not found to alter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The referral for dental general anaesthetic (DGA) is now deemed to be a treatment of 'last resort'1 for children in advanced stages of dental disease who are too anxious, or too immature, to undergo dental treatment by other means.2 The prospect of the DGA event has been found to provoke anxiety in 56–66% of children.3 These children are more dentally anxious than their peers, and their anxiety is also associated with greater distress at anaesthetic induction and increased postoperative morbidity.4 Psychological morbidity such as attention-seeking, tantrums, crying and nightmares is well recognised5,6 and is more likely in children who are younger, have pre-existing behavioural problems and pre-existing dental anxiety.3,4

Midazolam is a common premedicant at anaesthetic induction and might reduce post-anaesthesia behaviour disturbance. However, the evidence for efficacy varies between study populations and there is a balance between optimal therapeutic effect and delay of postoperative recovery.7,8,9

The authors have already reported that the children in this trial experienced significant cognitive deficit due to midazolam premedication when compared with placebo.10 This paper presents the data that evaluates the benefit of 0.2 mg/kg midazolam premedication on dental anxiety, anaesthetic induction distress, psychological morbidity and subsequent dental attendance.

Aims

To evaluate the benefit of midazolam 0.2 mg/kg deposited in the buccal pouch as a premedication upon child-reported dental anxiety, the observed behaviour of children at anaesthetic induction, postoperative psychological morbidity and continued dental attendance.

Method

A prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled, double blind clinical trial (registration number ISRCTN: 12026431; CTA 8000/13014) was conducted. Ethical approval was granted by the Area Ethics Committee (LREC DENTAL23; R&D Ref 03DN023).

Patients and recruitment

Children aged 5 to 10 years attending Glasgow Dental Hospital and School (GDH&S) for extractions were invited to participate after the need for DGA had been determined at a previous assessment visit. Following appropriate written consent, sampling was consecutive but limited by the capacity of the service and the availability of the research assistant (RA). Exclusion criteria included: patients who were not ASA I or II, those with learning disabilities, psychiatric disorder, non-fluency in English, or where the family had no telephone for follow-up.

Recruitment took place between October 2004 and January 2006, during which time 2,495 children (aged 3–10 years) attended the service.

Randomisation and blinding

The randomisation occurred at the time of the DGA visit using an automated computerised system. The research nurse (RN) telephoned a dedicated line and obtained a treatment code for each subject. The general anaesthetic staff and the RA remained blind until the code was broken following the completion of data collection and input.

Premedication administration

The RN placed the medicine in the buccal sulcus using a needle-less syringe. The midazolam subjects each received 0.2 mg/kg ('Epistat' preparation) while the placebo subjects received a similar volume prepared by the hospital pharmacy. The placebo premedication was designed to have a similar taste, texture and colour as the Epistat preparation. Children were encouraged to try not to swallow the medication but to allow mucosal absorption to occur. Approximately 30 minutes later, anaesthesia was induced by inhalation of sevoflurane, nitrous oxide and 40% oxygen and maintained with a similar mixture using a nasal mask or, occasionally though not routinely, a laryngeal mask. While asleep, an intravenous cannula was inserted into the child's hand. The children were monitored using ECG and pulse oximeter. Before the extractions, lignocaine with adrenaline infiltrations were routinely injected into the buccal mucosa adjacent to the extraction site to reduce bleeding and to provide postoperative pain relief. The RN remained with the child throughout the procedure and until the child was fully recovered and assessed as fit to discharge.

Data collection

All data were collected by the RA.

Demographic

Demographic information was collected from the parent at the time of recruitment. This included the level of social deprivation – 'DEPCAT'.11

Dental anxiety

Preoperative: dental anxiety was assessed before the administration of the premedicament, using the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS) augmented by the Facial Image Scale (FIS). The MCDAS has eight dental anxiety items. The score in each question may vary from 1 (relaxed) to 5 (extremely worried), thus the total score may range from 5 to 40 and is well validated.12,13 In order to help the child confirm their response on the MCDAS, they were asked to indicate which facial expression on the FIS also corresponded to their answer (facial expressions on the FIS range from smiling/relaxed through neutral to worried/sad).

Due to the young age of the present participants, however, it was inevitable that many of the children lacked experience of some of the dental procedures referred to in the MCDAS. Items for which the child had no experience were therefore omitted completely. Then, in order to render the scores comparable across children who answered different numbers of items, the average score was calculated for each child (that is, the sum of the scores for each of the individual answers, divided by the total number of answers). The resultant average scores (ranging from 0–5) were used to allow group comparisons.

It was also necessary to carry out a transformation of the MCDAS threshold scores for dental anxiety to equate them with the revised scoring procedure described above. The MCDAS norms classify scores of 8.8 as 'normal', scores of over 19 as 'anxious' and scores of over 31 as 'highly fearful'.12,13,15 Transformation of these scores to a scale range of 0 to 5 results a score of 8.8 being equal to 1.1, a score of 19 being equal to 2.4, and a score of 31 being equal to 3.9.

The MCDAS-FIS was repeated, using the same method outlined above, 48 hours later at a home visit.

Observed behaviour at anaesthetic induction

Observed behaviour at induction was recorded using the 'Houpt' scale16,17 as shown in Table 1, and was augmented with further criteria relating directly to the anaesthetic induction such as mask acceptance.

Pre- and postoperative emotional and behavioural assessment

The well validated and reliable Revised Rutter Scale for School-Age Children18,19,20,21 was completed by parents before premedication and at one week postoperatively by telephone. This scale describes parental ratings of their children's behavioural and emotional difficulties and provides both a total score and a score for pro-social behaviours. In addition, the Rutter Scale has sub-scores for a range of behaviours including hyperactivity [range = 0–6], conduct difficulties [range = 0–6] and emotional disturbances [range = 0–10]. With the exception of the pro-social behaviour score, lower scores indicate better behaviour.

Dental attendance

Dental appointments were arranged via the local community dental service clinic at one, three and six-months after discharge.

Statistical analysis

Database preparation and analysis was conducted by the University of Glasgow Department of Statistics. The behaviour at induction was tabulated by group. The Rutter Scale data were analysed using the R statistics package. This included analysis of covariance, with linear models to examine the effects of further covariates. ANCOVA was also used to assess the MCDAS-FIS scores. Significance was set at the 5% level.

The original power calculation was based on the estimated effect of midazolam upon cognitive performance, and is reported elsewhere.10

Results

One hundred and eighty-one subjects aged 5 to 10 years (mean 6.53 years) were recruited. Two patients were removed from the analysis when their study codes were found to have been reversed, leaving 179 subjects. The CONSORT flow chart (Fig. 1) shows patient recruitment and throughput. One subject from the placebo group was found to have contact dermatitis immediately following the DGA visit. This was unrelated to the premedication but she was withdrawn from postoperative follow-up. One subject did not receive a general anaesthetic following premedication. Table 2, showing demographic and clinical patient information, confirms that the midazolam and placebo groups were well matched.

Dental anxiety

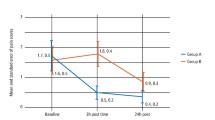

One hundred and thirty-eight children (n = 71 midazolam) provided data preoperatively and 48 hours after GA. Means (and standard deviations and ranges) were as follows. Preoperative dental anxiety: midazolam: 2.3 (0.78, 1.0–4.5) vs placebo: 2.26 (0.78, 1.0–4.6). Postoperative dental anxiety: midazolam: 2.4 (0.69, 1.29–4.5) vs placebo: 2.52 (0.78, 1.0–4.4).

An ANCOVA was conducted to explore the difference in dental anxiety between midazolam and placebo groups, with preoperative scores used as a co-variant. It was evident that many children had relatively low levels of preoperative anxiety which would not be reduced further by midazolam. Therefore, analysis was restricted to children scoring high in preoperative anxiety (MCDAS baseline score >2). These results demonstrated that midazolam premedication was then shown to be associated with a statistically significant reduction in dental anxiety at 48 hours relative to placebo [estimated difference 0.31, standard error 0.12, p = 0.001].

Observed behaviour at anaesthetic induction

One hundred and seventy-eight children provided data at anaesthetic induction. There was missing data for one child regarding mask acceptance; for another the general anaesthetic was cancelled following the premed for reasons unrelated to the study. When the results were tabulated (Table 1) and no observable differences were shown between the midazolam and placebo groups, no further statistical analysis was undertaken.

Pre- and postoperative emotional and behavioural assessment

Revised Rutter Scale for School Age Children: ANCOVA using age as a covariate was used. There were complete data for 153 participants (midazolam n = 81, placebo n = 72).

Total Rutter score: a significant effect (p = 0.048) was observed overall whereby children of 8 years of age and over showed a slight decrease in Rutter total score (that is, improvement) at one week compared to preoperative baseline score: midazolam (n = 13) change from baseline −2.3 (5.3); placebo (n = 12) change from baseline −1.7 (6.6). There were no significant differences, however, as a function of premedication.

Emotional and conduct Rutter sub-scales scores: there were no significant changes from baseline to one week in either the emotional or conduct behaviours (p = 0.071 and p = 0.214 respectively), and there was no effect of age.

Hyperactive Rutter sub-scale score: the midazolam and placebo groups both showed a significant, though clinically small, decrease in hyperactivity from the preoperative to the one week assessments: midazolam p = 0.04, placebo p = 0.02, pooled data p = 0.002 [midazolam baseline 2.03 (1.74), one week 1.68 (1.85); placebo baseline 2.20 (1.61), one week 1.64 (1.84)]. However, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups, nor was there a significant effect of age.

Pro-social Rutter score: there was a significant improvement in pro-social behaviours from preoperative to week one assessments (p = 0.002) [midazolam baseline 15.5 (3.37), one week 16.51 (3.12); placebo baseline 14.76 (4.04), one week 15.69 (3.25)], but, again, there were neither significant between-group differences nor any significant effect of age.

Dental attendance

Table 3 shows the parents' stated intention that their child would attend the community dental service for one, three and six-month follow-up compared to their actual attendance at the clinic. No differences were observed between the groups.

Discussion

The present study shows that 0.2 mg/kg of transmucosal midazolam did not improve children's behaviour at anaesthetic induction or reduce postoperative morbidity. However, midazolam premedication was shown to reduce dental anxiety in the most dentally anxious children. While the difference was statistically significant, it is unclear whether so small a change relative to placebo would have clinical significance.

The low dose of midazolam may be the reason for these largely negative results, further exacerbated by the fact that some of the midazolam might have been swallowed rather than absorbed transmucosally. The dose of 0.2 mg/kg is lower than the normal oral dosage of 0.3 mg/kg up to 1.0 mg/kg. However, while a higher dose of midazolam might have exerted more beneficial effects,22 Ko et al. have shown 0.2 mg/kg to be effective in reducing emergence agitation and postoperative analgesic requirements.23 Moreover, Erlandsson et al. have reported this dose to be effective for conscious sedation of uncooperative paediatric dental patients.24 Nevertheless, Calipel et al. reported that even 0.5 mg/kg oral midazolam premedication was not an effective premedicant, even when compared to non-pharmacological approaches.25

The authors had intended to administer a midazolam dose of 0.3 mg/kg but this was amended to 0.2 mg/kg on the insistence of the ethics committee, whose rationale was to reduce the risks of respiratory depression and disinhibited behaviour, given the very short interval between anaesthesia and discharge in this type of ambulatory service. As such, any benefit to the child of a 0.3 mg/kg dose for this ultra-short procedure might have been outweighed by the known adverse cognitive side effects on discharge.26 Interestingly, our cognitive function data confirmed significant short-term impairment even at this low dose.10

The subjects in the present study reflect the type of child referred for dental extractions under general anaesthesia in Scotland in general and in this unit in particular.27,28,30 Few recruits dropped out of the study and there was little missing data, and, surprisingly, only one child refused the premed – from the placebo group. On reflection, the results may have been influenced by the fact that both the RA and RN were in constant and emotionally supportive contact with the child and parent throughout. This might have been an unwitting confounding factor that is, nevertheless, well recognised in the literature.29,30 Thus, the supportive environment may in itself have achieved an effective level of preparation,31,32 to which the low dose of midazolam might have had little further to add. A 'placebo-effect' was clearly evident in that almost half of the control group was observed to be drowsy, disorientated or asleep before anaesthetic induction.

It is possible that the reduction in postoperative anxiety may be attributed to the amnesic effect of midazolam. A previous controlled study, on the same population though different recruits, confirmed that children self-reported significantly higher levels of dental anxiety postoperatively6 and so this finding is important. However, collecting self-reported child anxiety data using with the MCDAS was a challenge in the present study. The subjects were young and found to have little prior knowledge of local analgesia and sedation, and so their comprehension of some parts of the MCDAS was poor. Therefore, it was necessary for us to compute new MCDAS threshold values denoting 'anxiety'. Data were thus converted into mean scores and similar cut-off points for dental anxiety were determined using previously published literature.12,13,15 While sound methods were used to translate the scores, as this is not yet validated, even though it was derived in a logical way, our results should be interpreted with some caution.

For the sample as a whole, the behaviour of children appeared to improve after the DGA visit, with less hyperactivity and more positive engagement with their parents. The reason for such a positive behaviour change is unclear and it must be borne in mind that these improvements were clinically small in that the magnitude of the improvement was less than 10%. The fact that postoperative emotional behaviour was better in the few children who were aged 8 years and above probably reflects their more advanced developmental level, which confers greater understanding of the procedure and its effects with consequent benefits to their coping. This result is also consistent with evidence of a negative relationship between children's age and disturbed behaviour and non-cooperation33,34 and crying and restless behaviour after general anaesthesia.35 One might also speculate that perhaps the children felt better now that their toothache was alleviated; an alternative proposal might be that the children were concerned that if they misbehaved they would be sent for repeat treatment. It could also be possible that children were relieved that the GA process was behind them.

It could be argued that screening to exclude non-anxious subjects should have been performed before administration of a premedicant.36 However, the children in this sample were not undergoing ordinary elective surgical procedures; instead they had been referred for this radical treatment on account of their poor dental condition, toothache and likely pre-existing dental anxiety.6,37 The fact that the population in the present study had preoperative total Rutter scores approaching the previously validated indicator for clinically significant 'disturbance' is evidence of their poor preoperative behavioural and emotional state.

Despite parental agreement to continue to attend for dental follow-up, the results in this regard were disappointing, though not surprising given the previous dental history and social deprivation scores of the sample. It is possible that some parents preferred to attend their general dental practitioner. However, it is common for children to have lapsed registration following the DGA event.

Overall, this randomised placebo-controlled trial in children undergoing general anaesthesia for dental extractions has shown that 0.2 mg/kg midazolam placed in the buccal pouch did not benefit dental anxiety generally; however, the most dentally anxious children experienced a reduction postoperatively. Behaviour at anaesthetic induction, postoperative psychological morbidity and subsequent dental attendance were not found to differ between the premedication groups.

References

Rayner J, Holt R, Blinkhorn F, Duncan K ; British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on oral health care in preschool children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2003; 13: 279–285.

Macpherson L M, Pine C M, Tochel C, Burnside G, Hosey M T, Adair P . Factors influencing referral of children for dental extractions under general and local anaesthesia. Community Dent Health 2005; 22 : 282–288.

Lumley M A, Melamed B G, Abeles L A . Predicting children's pre-surgical anxiety and subsequent behaviour changes. J Pediatr Psychol 1993; 18: 481–497.

Hosey M T, Macpherson L M D, Adair P, Tochel C, Burnside G, Pine C . Dental anxiety, distress at induction, and postoperative morbidity in children undergoing tooth extraction using general anaesthesia. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 39–43.

Bridgman C M, Ashby D, Holloway P J . An investigation of the effects on children of tooth extraction under general anaesthesia in general dental practice. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 244–247.

Millar K, Asbury A J, Bowman A W, Hosey M T, Musiello T . The effects of brief sevoflurane-nitrous oxide anaesthesia upon children's postoperative cognition and behaviour. Anaesthesia 2006; 61: 541–547.

Lonnqvist P A, Habre W . Midazolam as a premedication: is the emperor naked or just half dressed? Paediatr Anaesth 2005; 15: 263–265.

Howell T K, Smith S, Rushman S G, Walker R W, Radivan F . A comparison of oral transmucosal fentanyl and oral midazolam for premedication in children. Anaesthesia 2002; 57: 798–805.

Johnson T N, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Goddard J M, Tanner M S, Tucker G T . Contribution of midazolam and its 1-hydroxy metabolite to preoperative sedation in children: a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis. Br J Anaesth 2002; 89: 428–437.

Millar K, Asbury A J, Bowman A W et al. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of the effects of Midazolam premedication on children's postoperative cognition. Anaesthesia 2007; 62: 923–930.

Carstairs V, Morris R . Deprivation: explaining differences in mortality between Scotland and England and Wales. BMJ 1989; 299: 886–889.

Humphris G M, Morrison T, Lindsay S J E . The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health 1995; 12: 143–150.

Wong H M, Humphris G M, Lee G T R . Preliminary validation and reliability of the Modified Child Anxiety Scale. Psychol Rep 1998; 83: 1179–1186.

Buchanan H, Niven N . Validation of a Facial Image Scale to access child dental anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent 2002; 12: 47–52.

Campbell C, Hosey M T, McHugh S . Facilitating coping behaviour in children before dental general anaesthesia: a randomised controlled trial. Paediatr Anaesth 2005; 15: 831–838.

Hosey M T, Blinkhorn A S . An evaluation of four methods of quantifying the behaviour of anxious child dental patients. Int J Paediatr Dent 1995; 5: 87–95.

Houpt M I, Kupietzky A, Tofsky N S, Koenigsberg S R . Effects of nitrous oxide on diazepam sedation of young children. Pediatr Dent 1996; 18: 236–241.

Rutter M . Rutter Scales. In Child psychology portfolio. Berkshire: NFER-Nelson, 1993.

Hogg C, Richman N, Rutter M . Revised Rutter Scales. In Child psychology portfolio. London: Nelson, 2004.

Elander J, Rutter M . An update on the status of the Rutter Parents' and Teachers' Scales. Child Psychol Psychiatry Rev 1996; 1: 31–35.

Elander J, Rutter M . Use and development of the Rutter Parents' and Teachers' Scales. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1996; 6: 63–78.

Horiuchi T, Kawaguchi M, Kurehara K, Kawaraguchi Y, Sasaoka N, Furuya H . Evaluation of low dose ketamine premedication in children: a comparison with midazolam. Paediatr Anaesth 2005; 15: 643–647.

Ko Y P, Huang C J, Hung Y C et al. Premedication with low-dose oral midazolam reduces the incidence and severity of emergence agitation in paediatric patients following sevoflurane anaesthesia. Acta Anaesth Sinica 2001; 39: 169–177.

Erlandsson A L, Backman, B, Stenstrom A, Stecksen-Blicks C. Conscious sedation by oral administration of midazolam in paediatric dental treatment. Swed Dent J 2001; 25: 97–104.

Calipel S, Lucas-Polomeni M M, Wodey E, Ecoffey C . Premedication in children: hypnosis versus midazolam. Paediatr Anaesth 2005; 15: 275–281.

Girdler N M, Fairbrother K J, Lyne J P et al. A randomised crossover trial of postoperative cognitive and psychomotor recovery from benzodiazepine sedation. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 335–339.

Hosey M T, Bryce J, Harris P, McHugh S, Campbell C . The behaviour, social status and number of teeth extracted in children under general anaesthesia: a referral centre revisited. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 331–334.

A national audit to determine the reasons for the choice of anaesthesia in dental extractions for children across Scotland. Clinical Resource and Audit Group of the Scottish Executive Health Department, Project number 99/42. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2002.

Turkington D, McKenna P J . Is cognitive-behavioural therapy a worthwhile treatment for psychosis? Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182: 477–479.

Parsons H M . What happened at Hawthorne? New evidence suggests the Hawthorne effect resulted from operant reinforcement contingencies. Science 1974; 18 3: 922–932.

Schmidt C K . Preoperative preparation effects on immediate preoperative behaviour, postoperative behaviour and recovery in children having same-day surgery. Matern Child Nurs J 1990; 19: 321–330.

Bates T A, Broome M . Preparation of children for hospitalization and surgery: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Nurs 1986; 1: 230–239.

Keaney A, Diviney D, Harte S, Lyons B . Postoperative behavioural changes following anaesthesia with sevoflurane. Paediatr Anaesth 2004; 14: 866–870.

Seed R, Boardman C, Davies M . Cooperation with preoperative cardiovascular monitoring among children for chair dental general anaesthesia. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006; 88: 207–209.

Cole J W, Murray D J, McAllister J D, Hirshberg G E . Emergence behaviour in children: defining the incidence of excitement and agitation following anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth 2002; 12: 42–447.

Holn-Knudsen R, McKenzie C . Distress at induction of anaesthesia in children. A survey of incidence, associated factors and recovery characteristics Paediatr Anaesth 1998; 18: 383–392.

Department of Health. A conscious decision: a review of the use of general anaesthesia and conscious sedation in primary dental care. Report chaired by the Chief Medical Officer and Chief Dental Officer. London: Department of Health, 2000.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to express their thanks to the staff of the general anaesthetic extraction service at Glasgow Dental Hospital and School (now relocated to the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Yorkhill), with particular thanks to Sister Alison Anderson. The research was supported by grant CZH/4/139 from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive Health Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hosey, M., Asbury, A., Bowman, A. et al. The effect of transmucosal 0.2 mg/kg midazolam premedication on dental anxiety, anaesthetic induction and psychological morbidity in children undergoing general anaesthesia for tooth extraction. Br Dent J 207, E2 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.570

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.570

This article is cited by

-

Interrater agreement between children’s self-reported and their mothers’ proxy-reported dental anxiety: a Chinese cross-sectional study

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Providing sealants at the general anaesthetic assessment visit for children requiring caries-related dental extractions under general anaesthetic: a pilot randomised controlled trial

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Prevention in the context of caries-related extractions under general anaesthesia: an evaluation of the use of sealants and other preventive care by referring dentists

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Lessons learned on recruitment and retention in hard-to-reach families in a phase III randomised controlled trial of preparatory information for children undergoing general anaesthesia

BMC Oral Health (2017)

-

Comparing the profile of child patients attending dental general anaesthesia and conscious sedation services

British Dental Journal (2017)