Key Points

-

Updates and clarifies the law relating to gaining valid consent for the benefit of dental healthcare professionals.

-

Illustrates the audit performance of hospital consultant orthodontists in their knowledge and understanding of informed consent against which future comparisons can be made.

-

Provides a means to replicate and extend the audit to other branches of dental practice.

Abstract

Objective To determine the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists.

Design A questionnaire which covered a range of legal issues on informed consent as it pertains to clinical practice in three of the four nations of the United Kingdom.

Setting Hospital orthodontic departments in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Subjects and methods A questionnaire was initially issued to 14 consultant orthodontists working in the East of England as a regional audit project on informed consent in 2005. After the completion of the audit in 2006, the pilot data were used to refine the questionnaire for wider circulation. The project was then submitted to the British Orthodontic Society (BOS) clinical effectiveness committee which subsequently gave its endorsement for national circulation. The questionnaire was then sent to 216 other consultants in June 2007, with two further postings to non-responders before the survey was closed four months later. The standard required for clinical practice to be lawful is that all of the questions should be answered correctly.

Results Of the 233 consultant orthodontists who were invited to participate, 183 complied (78.5%) and 50 did not (21.5%). Of those who responded, 179 answered the questionnaire (76.8%) while four had either resigned or retired (1.7%). Out of the 21 answers to the 11 questions that were posed, the mean, median and mode correct response rates were 12 (57%), 11 (52%), and 10 (48%) respectively. The areas which were found to have the poorest level of understanding included what explanations patients need from clinicians in order for them to give consent, how to fully judge if a patient is capable of giving consent, how to manage a patient deemed incapable of giving consent, the legal status of fathers consenting on behalf of their children, whether consent forms have to be re-signed if the start of treatment is delayed by six months or more, and that dentists referring a patient for treatment requiring a general anaesthetic have the same duty to receive consent for the anaesthesia as do the clinicians who will be performing the surgical procedure.

Conclusions The results of this audit indicate certain key areas of deficiency in the knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists. The findings provide an opportunity for all clinicians to improve their education and therefore their potential to comply with both the ethical obligation and the legal requirement of gaining valid consent before the start of any treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2000, the publication of the National Health Service (NHS) plan recognised the importance of each patient's right to be able to give informed consent,1 and in the same year, the British Dental Association issued a comprehensive advice sheet on consent.2

A year later the Department of Health published a guide to consent for the examination or treatment of a patient,3 together with guidance on its implementation4 as well as the key legal points of consent as it pertains to clinical practice in England.5 These same principles and guidance were then published in a suitably modified form for practice in Northern Ireland two years later.6,7 All of them are based on case law and are meant to provide clinicians with unequivocal guidance as to how valid consent can be gained from those patients who are capable of giving it, as well as how treatment may be lawfully delivered to those who are not, both of which are mandatory legal requirements.3

Yet a proportion of healthcare professionals have either not read or cannot reliably recall these guidelines, so much so that the full legalities of obtaining valid consent are incompletely understood by most medical staff.8 Equally, there is reportedly some evidence that dentists may not always understand the process of consent nor when it should be applied,9 with additional anecdotal evidence that sometimes it is also completely omitted.10

Nevertheless, it has been acknowledged that these deficiencies can be remedied through appropriate education,8 and for this reason it was decided to undertake a regional audit on informed consent amongst a small number of consultant and training grade group (TGG) orthodontists, before subsequently extending the survey nationally.

Subjects and method

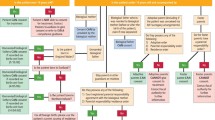

In June 2005, a questionnaire on informed consent was issued to 14 consultant and 16 TGG orthodontists who worked in the East of England to answer as a survey prior to a subsequent regional audit (Fig. 1). It was based in part on one that had been used to test both the knowledge and understanding of this topic amongst doctors and healthcare professionals in Bristol.8 The questions covered areas of fundamental importance, difficult clinical situations and common consent dilemmas. As with those questions that were replicated from the previous publication,8 the answers to this survey's new additional questions were also based on the Department of Health's guidelines as well as those of the General Dental Council (GDC), and they were similarly validated by an independent medico-legal expert.

After reviewing the responses and agreeing the audit standards to be met, the questionnaire was re-issued the following year and completed in September 2006. These data were then used to refine the questionnaire for possible national circulation and for this the project was first submitted to the British Orthodontic Society (BOS) clinical standards committee in November 2006 for its endorsement. This was given in March 2007, after some minor alterations that had been suggested by three of the committee members who had answered the questionnaire had been incorporated.

Because the law in Scotland differs substantially in relation to consent by children and by adults with incapacity,11,12,13 it was decided that the subsequent survey should be limited to the principality of Wales and the other two nations which comprise the United Kingdom. Therefore in June 2007 it was circulated to 216 consultant orthodontists and 207 TGGs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, using an address list supplied by the BOS. The questionnaire that was used can be seen in Appendix 1.

All participants were asked to denominate their returns using their name and GDC number so that it would be possible to identify non-responders in order to facilitate repeat mailings to them and so reduce bias. Nevertheless, an identifiable code was also included on the return envelopes in the event of any responders who, despite this request, still returned an unidentifiable completed questionnaire. However, assurances were given that the data would be kept confidential and the results would be rendered anonymous.

Re-contact was made with non responders on two further occasions in July and September 2007, using personalised letters, stamped addressed envelopes and when necessary, different addresses to those initially supplied by the BOS, as derived from the GDC register. The survey was then closed at the end of 2007.

The data were collected and entered onto Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond WA, USA). While the results of this study solely relate to the performance of the consultant orthodontists, the information on the separate performance of the TGGs may be found elsewhere.14

Results

Figure 1 illustrates that of the 233 consultant orthodontists who were approached to complete the survey, 183 complied (78.5%) and 50 did not (21.5%). Of those who responded, 179 answered the questionnaire (76.8%) while four had either resigned or retired (1.7%).

Overall, out of the 21 potential answers to the 11 questions that were posed in the questionnaire, the mean, median and mode correct response rates were 12 (57%), 11 (52%), and 10 (48%) respectively. In particular, the performance of the consultants for each question was as follows:

Question 1

For a patient to be able to consent to a course of treatment, what must the clinician explain to them?

Table 1 shows that all of the consultants knew this would involve explaining the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment, but 40% did not realise that this should also include the risks and benefits of any alternative treatment, and 70% did not know that the potential consequences of remaining untreated should be outlined as well (Chapter 1: 'Seeking consent', paragraph 4 and 5.3).3

Question 2

For a clinician to judge whether a patient has the capacity to give informed consent, what must the patient be able to demonstrate after all explanations have been given?

Table 2 illustrates that nearly all of the consultants appreciated this would involve the patient in both understanding and recalling the information they had been given, but 80% of them had not realised they also had to judge whether the patient could use and weigh this information when they came to decide what they wanted to do (Chapter 1: 'Seeking consent', paragraph 2).3

Question 3

In the case of a conscious adult deemed incapable of giving consent for a course of treatment that cannot be delayed, explain how best to proceed.

Table 3 shows that apart from involving the carers and relatives in the discussion of the patient's potential management (Chapter 2: 'Adults without capacity', paragraph 6.1),3 one half or more of the consultants were unsure of what else to do, namely to ascertain whether any advance directives had been made by the patient about their healthcare management if and when they were previously competent (Chapter 1: 'Seeking consent', paragraph 19),3 to seek the support of a second professional opinion (Consent form 4. For adults who are unable to consent),4 and to only carry out treatment deemed to be in the patient's best interest (Chapter 2: 'Adults without capacity', paragraphs 3 and 6).3

Question 4

(a) In the case of a patient aged between 16 and 18 who is deemed incapable of giving consent, can the patient's mother legally give consent? and,

(b) Once the same patient reaches the age of 18, can his next of kin sign a consent form on his behalf?

Table 4 shows that overall, 146 consultants (82%) answered correctly in the affirmative for the first part of the question (Chapter 3: 'Children and young people', paragraph 9),3 while 111 (62%) answered correctly in the negative for the second part (Chapter 2: 'Adults without capacity', paragraph 1).3

However, out of the four possible ways of answering yes or no to this paired question, Table 4 also shows that only 80 consultants (45%) answered both parts correctly (combination 2), with 66 (37%) just answering the first part correctly (combination 1) and 31 (17%) just answering the second part correctly (combination 3). Only two consultants (1%) answered both parts incorrectly (combination 4).

Question 5

If a competent child under 16 years of age consents to undergo a course of treatment, can the child's mother legally override that consent?

One hundred and twenty-seven consultants (71%) answered this correctly that in the case of a 'Gillick competent' child she cannot (Chapter 3: 'Children and young people', paragraphs 5 and 6).3

Question 6

If a competent child under 16 years of age refuses to undergo a course of treatment, can the child's father legally consent instead? (The answer needs to be qualified by two conditions).

Table 5 shows that overall 134 consultants (75%) answered yes to this question. In addition, a total of 80 consultants (45%) gave the first correct qualifier to the question, namely that this should, however, be restricted to when the child is otherwise at risk of grave or irreversible mental or physical harm (Chapter 3: 'Children and young people', paragraphs 8 and 8.1),3 while 70 consultants (39%) gave the second correct qualifier, namely that the father could only do so if he had been married to the mother at the time of either the child's conception or birth, or if not, if he had been given parental responsibility by a court order, or if subsequently he married the mother (Chapter 3: 'Children and young people', paragraph 10).3

However, Table 5 also shows that of the consultants who answered affirmatively, only 26 (14%) qualified their answer by correctly citing both of the required conditions (combination 3), with 54 (30%) just citing the first qualifying condition (combination 2), 44 (25%) just the second (combination 4), and 10 (6%) citing neither of them (combination 1). In addition, 45 consultants (25%) mistakenly believed that a father could not override his child's refusal to receive treatment under any circumstances, nor did they give either the required exception or condition (combination 5).

Question 7

Is a signed consent form essential before non-urgent treatment?

One hundred and twenty-nine consultants (72%) correctly answered that it was not (Chapter 1: 'Seeking consent,' paragraphs 11 and 11.1).3

Question 8

According to current Department of Health guidelines, can all major treatment complications with an incidence of less than 1% be omitted from being discussed during the process of obtaining consent?

Ninety-eight consultants (55%) correctly answered no they cannot. Rather, it is advisable to inform the patient of any material or significant risks in the treatment, as well as the alternatives of doing nothing (Chapter 1: 'Seeking consent,' paragraph 5.3).3

Question 9

According to current Department of Health guidelines, if a patient has signed a consent form more than six months prior to the treatment starting, must the patient re-sign the form for validity?

Forty-three consultants (24%) correctly answered no they need not. If a patient gives valid consent, it remains valid for an indefinite duration unless the patient withdraws it. Reconfirmation of consent is only necessary if the patient's condition changes, or if new information regarding the previously proposed treatment comes to light (Chapter 1: 'Seeking consent', paragraph 16).3

Question 10

In those cases where some aspect of the patient's dental treatment cannot be performed without a general anaesthetic, who has responsibility for obtaining the anaesthetic consent?

While 154 consultants (86%) responded that a dentist who was to provide treatment under a general anaesthetic (GA) would need to obtain consent for the anaesthetic from the patient or parent, only 30 consultants (17%) also knew that if a clinician was to refer a patient for treatment under a GA they would have the same ethical obligation.

Otherwise, 138 consultants (77%) listed the anaesthetist as being a person with responsibility for the anaesthetic consent in such circumstances.

Question 11

According to the General Dental Council's May 2005 standards guidance, whenever a patient returns to start a course of treatment following an examination or assessment, must they be given a written treatment plan?

One hundred and eight (60%) of the consultants correctly answered that they must (paragraph 1.6).15

Discussion

While consultant and specialist orthodontists have been surveyed before on how they obtain consent in practice,16,17 this is the first study to audit the level of knowledge and understanding of the law as it pertains to gaining valid patient consent amongst a consultant sub-group of dental surgeons. As such, despite being given the assurance that the results would be rendered anonymous and the data would be kept confidential, the fact that the performance of named individuals was being scrutinised could perhaps explain why the response rate of 78.5% was lower than the 90% that had been found in a previous, less challenging consultant orthodontist survey.16

Nevertheless, it was higher than the 69% response rate that had occurred in the informed consent investigation of orthodontic specialist practitioners.17 However, because just over a fifth of the consultant orthodontists did not participate, there is a possibility that the results of this audit could have been biased towards a more favourable consultant performance. This would be based on the assumption that perhaps those consultants who had taken part had kept themselves better informed on consent publications and so had felt less threatened to respond compared to those who had not.

However, out of the 21 answers to the 11 questions that were posed, on average they correctly provided only 12 of them (57%), and yet to fulfill their ethical obligation and legal requirement of being in a position to gain valid consent, the only acceptable 'audit' standard would have been for all of them to have been answered correctly. In this respect, the only question where this was achieved was in the first answer to question one, namely that for a patient to be able to consent to a course of treatment, the clinician must explain to them the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment. A similar overall level of proficiency amongst 50 doctors has also been found in an earlier report from which some of this study's questions were replicated, namely that their average score for answering their twelve questions was only 53.7%.8

With further regard to question one and what explanations patients need from clinicians in order to consent to treatment, 60% of the consultants also knew that this should additionally include the risks and benefits of any alternative treatments. In comparison, the explanation of alternative options by only 25% of junior medical staff has been found to be much poorer for patients who are consented for surgery.18

While the four answers to question three on how best to manage an incapable adult who needs treatment were valid at the time the audit began, towards the end of the study the full force of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 200519 had come into effect by October 2007.20 Although much of the Department of Health's former 2001 guidance in this area still remains pertinent, there are now some notable changes which clinicians need to take account of in order to continue practising lawfully under such circumstances. Indeed, as case law continues to evolve and as further legal developments occur, health professionals have a duty to keep themselves informed of such developments which may have a bearing on their practice (Introduction, paragraph 4).3

In particular, the majority of the MCA 2005 applies to those aged 16 years and over (section 2 {5}) and under its provisions, capable adults aged 18 years and above are able to make binding 'advance decisions' refusing certain treatments should they lose capacity at some future date. Nevertheless, these are only applicable if the future treatment in question is the treatment specified in the advance decision, and so long as the circumstances that are also specified therein are not absent (Part 1. Persons who lack capacity. 'Validity and applicability of advance decisions', paragraph 25).19

Similarly, adults can delegate decisions about health and financial matters to a designated person called a donee, under a 'lasting power of attorney', so that person can make decisions in their stead should they lose capacity in later life.20

However, the Act still specifies that if an adult lacks capacity, no one else can give or withhold consent for that person and any subsequent treatment must remain in the person's best interest. Clinicians must have a 'reasonable belief' that capacity is lacking before treatment can be lawfully carried out without a patient's consent. Under the Act, assessments of capacity still require discussions with those directly involved in the patient's care, namely family members, lay and professional carers, but where treatments may be complex or have long-term effects, or where capacity is in dispute, referral to a consultant psychiatrist or psychologist for a capacity assessment may be appropriate. Ultimately though, it is the treating dentist who has to determine capacity, with all of the others cited above merely acting in an advisory role.20

To determine what treatment is in the patient's best interests, the dentist should take into account and, if appropriate, consult anyone named by the patient as a person to be consulted, any carer or person interested in their welfare, any donee of a lasting power of attorney, any court 'deputy' appointed by the Court of Protection, and any independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) who would be appointed by an NHS body where serious treatment is being considered and where there is no other person other than the paid carer to determine what would be in the patient's best interests. Nevertheless, where disputes between clinicians and, for example, a donee of lasting power of attorney arise as to what treatment does constitute a patient's best interests, referral to the Court of Protection may be required to resolve the conflict.20

On the same subject, in the first part of question four as to whether a mother can legally consent on behalf of her 16 to 17 year old incapable child, there is a degree of overlap between the provisions of the MCA 2005 which applies to over 16 year olds, and the exercise of parental responsibility under the Children Act 1989, which applies to under 18 year olds.21

This overlap is recognised under section 21 of the MCA 2005, where the Lord Chancellor may 'by order make provision as to the transfer of proceedings relating to a person under 18, from the Court of Protection to a court having jurisdiction under the Children Act 1989 and vice versa.' This is particularly relevant where a dispute exists between the mother and the clinician as to what constitutes treatment that is in the young person's best interests. Where no such conflict exists, then under the provision of the Children Act 1989, the mother can legally give consent on behalf of her 16 to 17 year old incapable child.

In the second part of question four as to whether the next of kin of an 18 year old adult who is incapable of giving consent can sign a consent form for treatment on their behalf, 111 (62%) of the consultants answered this part in isolation correctly (Table 4). An identical percentage level of knowledge that no one else can consent on behalf of an incapable adult has also been found amongst doctors.8

However, out of the four possible ways of answering yes or no to the pair of questions in question four, Table 4 shows that only 80 (45%) consultants answered both parts correctly (combination 2). This means that out of the 146 consultants who answered the first part of the question in isolation correctly, and out of the 111 who answered the second part of the question in isolation correctly, 66 (37%) and 31 (17%) of them respectively were perhaps more the fortunate product of chance, rather than the existence of a complete understanding, being a reflection instead of the mistaken presumptions these consultants had that regardless of the incapable patient's age, their next of kin could either always or never consent on their behalf.

Since one of the acknowledged roles of the NHS consultant orthodontist service is to provide advice and treatment for patients with special needs,22 a complete comprehension of consent in this area is essential if consultants are to discharge this duty lawfully.

With regard to the answer for question five, that a mother cannot override the consent of a Gillick competent child who is under 16 years of age, 71% of the consultant orthodontists gave the correct response, which was slightly better than the 68% of doctors who similarly responded to the same question in a previous report.8

In question six, overall 134 (75%) of the consultant orthodontists answered affirmatively that a father could legally consent to treatment that his competent child was refusing to undergo (Table 5), and this was noticeably better than the 50% combined performance of doctors in general or than the 30% performance of senior doctors in particular who had answered the same question previously.8

However, disappointingly just 26 (14%) of the consultants correctly knew that this could only be done on those occasions when the child would otherwise be at risk of grave or irreversible mental or physical harm, and then only if the father had been married to the mother at the time of the child's birth, or if not, if he had been given parental responsibility by a court order,21 or if he had become registered as the child's father, or if he and the mother had made a parental responsibility agreement which provided him with responsibility for the child.23

For a dental specialty that is predominantly involved in treating young people, the correct answers to questions five and six are important to know, because there are occasions when what a child will or will not consent to undergo comes into conflict with the wishes of their parent. Equally, while the majority of orthodontic patients are usually accompanied by their mothers, on occasions their fathers will attend instead, and for the purposes of gaining valid consent, the legal conditions that are placed upon them must be known by the clinicians if the child's subsequent treatment is to be lawful. Indeed, previous studies have shown that 4% of children who have undergone surgery have been operated on without valid consent because their fathers had signed the consent form when they did not have legal parental responsibility,24 and a similar situation has also been found in the case of 20% of those children who have attended for dental treatment with their father.25

With regard to question seven as to whether a signed consent form is essential before non-urgent treatment, 129 (72%) of the consultants correctly answered that it is not, and this is considerably better than the understanding amongst doctors where 70% incorrectly believed the opposite was true.8

Question eight asked if the Department of Health guidelines permitted the non-disclosure of any major treatment complications with an incidence of less than 1% during an informed consent discussion, and 98 (55%) of the consultants correctly answered that they did not. This is markedly better than the understanding of other medical healthcare professionals, where only 8.5% of them knew that this statement was false.8 However, this figure of a 1% major treatment risk has become deep rooted in healthcare professionals belief of consent, but it has no legal basis,8 and so the concept of only telling patients about major complications with a greater than 1% risk, or indeed about any minor complications with a greater than 10% risk are both untenable.26

This is because the test of liability in relation to the clinician's duty to warn a patient of the risks of the proposed treatment is the same as the test applicable to diagnosis and treatment, as set out in the House of Lords decision of Sidaway.27 In this regard the clinician has to act in accordance not only with a practice accepted at the time as proper by a responsible body of medical opinion (the Bolam test),28 but also with the Bolitho modification,29 that the body of opinion should be reasonable and responsible and the opinion should be logical.30 Indeed, the Court of Appeal has ruled that it is the responsibility of clinicians to divulge any significant risk which would affect the judgement of a reasonable patient.31 Lord Steyn in Chester has also stated that 'In modern law, medical paternalism no longer rules and a patient has a prima facie right to be informed by a surgeon of a small, but well established, risk of serious injury as a result of surgery.'32 The problem is that there is a huge variation in the risks which judges deem to be acceptable, and so the standard of informing patients about risks is evolving as it shifts from those which are considered to be relevant to a responsible dentist to those of a reasonable patient.33

The answer to question nine, that a patient does not need to re-sign a consent form at any subsequent stage unless either their condition has since changed or if new information about the previously proposed treatment has come to light was only correctly answered by 43 (24%) of the consultants. Nevertheless, this is still double the percentage of the 118 medical healthcare professionals who correctly answered the same question previously.8

With regard to question ten as to who has responsibility for obtaining consent for a dentally required general anaesthetic, the GDC in its standards guidance ('Annex. Statement on providing dental treatment under general anaesthesia and conscious sedation')34 has stated that it supports the recommendations set out in the Department of Health's (England) publication A conscious decision – a review of the use of general anaesthesia and conscious sedation in primary care, namely that the referring dentist must discuss the risks associated with all methods of pain and anxiety control so the patient can make an informed choice, and they must also include a clear justification for the use of a general anaesthetic in the referral letter they send (Chapter 3: 'Review of current standards', pages 21-22).35

Equally, before a general anaesthetic for dental treatment is administered, written evidence of consent must be obtained by the dentist who will be treating the patient, after all the alternatives have been explored and the risks of the procedure made clear to the patient or the carer (Chapter 3: 'Case selection and consent', pages 29-30).35

In addition, this GDC stance of holding dentists responsible for ensuring that patients have all the necessary information is acknowledged elsewhere, with the responsibility of obtaining consent being shared as a consequence between the dentists and the anaesthetist in such cases (III: When should consent be sought? Seeking consent for anaesthesia, paragraph 8).4

For medical practitioners, it is the sole responsibility of the anaesthetist to consent the patient regarding the risks and benefits of general anaesthesia, and this understanding has been shown to exist before amongst 72% of healthcare professionals in general and 89% of anaesthetists in particular.8 While a similar percentage of the consultant orthodontists in this study were equally aware of this obligation (77%), the vast majority of them (83%) were completely unaware of the same stipulation that the GDC places on any dentist who initiates a referral for a patient who will require some aspect of their dental treatment to be carried out under a general anaesthetic. In the case of a hospital orthodontist service, this would commonly include either the multi-disciplinary management of impacted teeth or the correction of facial deformity with orthognathic surgery.22

While case law has not so far set this standard, it has been acknowledged that the standards expected of health professionals by their regulatory bodies may at times be higher than the minimum required by law. Legal requirements in negligence cases have historically been based on the standards set by the professions for their members, and so where standards required by professional bodies rise, it is likely that the legal standards will rise accordingly (Introduction, paragraph 7).3

With regard to the final question as to whether a written treatment plan must be given to all patients who return to start a course of dental treatment following an examination or assessment as prescribed by the GDC, 108 (60%) of the consultants knew this to be the case.

Aside from the fact that this facility gives patients more time to make a decision (paragraph 1.11),15 the provision of written information has also been shown to significantly improve patients' retention and recall.18,36,37,38 This is a factor in the second best answered question in the present study which fell just short of the 100% audit standard, namely that 96% of consultants knew that for them to be able to judge whether a patient was capable of giving informed consent, the patient had to be able to demonstrate their ability to both understand and retain the information they had been given.

In addition, when only verbal details about proposed treatments are provided, the validity of any subsequent consent can be severely compromised. For example, in one study where parents had been given structured verbal information about their child's forthcoming dental treatment under a GA, their consent was subsequently found to be actually invalid in 40% of cases. This was simply because one or more of the three fundamental treatment keys, such as what type of anaesthetic was to be used, which type of teeth and how many were to be extracted, could not be recalled immediately after the consent forms had been signed.39

Indeed, where the treatment of children is concerned, the more directly they are involved in the consent process with their parents, the greater the overall level of comprehension and satisfaction there is with the whole outcome.40

But there is no doubt that the time and effort which is spent on increasing patient understanding in order to secure valid consent comes at a price. Indeed, one study has found that to consent a patient properly takes at least double the usual time.18

Conclusions

The results of this audit have indicated certain key areas of deficiency in the knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists. It is likely that a similar situation exists among other dental professionals and so these findings provide an opportunity for all clinicians to improve their education and therefore their ability to comply with both their ethical obligation and legal requirement to gain valid consent from patients before they start treatment. Within the hospital dental service this could be achieved by regional audit groups using the same questionnaire to repeat the investigation in order to improve local compliance.

References

Department of Health. The NHS plan. London: HMSO, 2000. http://www.dh.gov.uk/ prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4055783.pdf.

British Dental Association. Ethics in dentistry. London: BDA, 2000. Advice sheet B1. http://www.bda.org/advice/docs/B1.pdf.

Department of Health. Reference guide to consent for examination or treatment. London: Department of Health, 2001. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/ Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4006757

Department of Health. Good practice in consent implementation guide: consent to examination or treatment. London: Department of Health, 2001. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/ PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4005762

Department of Health. 12 key points on consent: the law in England. London: Department of Health, 2001. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/ dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_075159.pdf.

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. Reference guide to consent for examination, treatment or care. Belfast: Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, 2003. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/consent-referenceguide.pdf.

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. Good practice in consent: consent for examination, treatment or care. Belfast: Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, 2003. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/consent-guidepart1.pdf.

Chadha N K, Repanos C . How much do healthcare professionals know about informed consent? A Bristol experience. J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel 2004; 2: 328–333.

Milan R . Consent to orthodontic treatment. Br Dent J 2007; 202: 616.

Speirs F . Informed consent. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 352.

Henwood S, Wilson M A, Edwards I . The role of competence and capacity in relation to consent for treatment in adult patients. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 18–21.

Office of Public Sector Information. Age of legal capacity (Scotland) Act 1991 (c.50). London: The Office of Public Sector Information, 1991. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1991/Ukpga_19910050_en_1.

Office of Public Sector Information. Adults with incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. London: The Office of Public Sector Information, 2000. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/legislation/scotland/acts2000/asp_20000004_en_1.

Sharma P, Chate R A C . An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst training grade group orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. J Orthod 2009; In press.

General Dental Council. Principles of patient consent. London: General dental council, 2005. http://www.gdc-uk.org/NR/rdonlyres/ FFD61DA5-A09E-4B38-8FFB-BA342E9F0AF4/16688/147163_Patient_Cons.pdf.

Gardner A W, Warren Jones J . An audit of the current consent practices of consultant orthodontists in the UK. J Orthod 2002; 29: 330–334.

Chappell D, Taylor C . A survey of the consent practices of specialist orthodontic practitioners in the North-West of England. J Orthod 2007; 34: 36–45.

Ibrahim T, Ong S M, Taylor G J S C . The new consent form: is it any better? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2004; 86: 206–209.

Office of Public Sector Information. Mental Capacity Act 2005. London: The Office of Public Sector Information, 2005. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/ukpga_20050009_en_1.

Emmett C . The Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its impact on dental practice. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 515–521.

Office of Public Sector Information. The Chidren Act 1989. London: The Office of Public Sector Information, 1989. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1989/Ukpga_19890041_en_1.

British Orthodontic Society. The role of the hospital consultant orthodontist service. London: British Orthodontic Society, 2007.

Office of Public Sector Information. Adoption and Children Act 2002. London: The Office of Public Sector Information, 2002. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2002/ukpga_20020038_en_1.

Elmalik K, Wheeler R A . Consent: luck or law? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2007; 89: 627–630.

Lal S M L, Parekh S, Mason C, Roberts G J . The accompanying adult: authority to give consent in the UK. Int J Paediatr Dent 2007; 17: 200–204.

Campbell B . New consent forms issued by the Department of Health. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2004; 86: 457–458.

Sidaway v Board of Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital. 1985 1 AC 871.

Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee. 1957 1 WLR 582 2 All ER 118.

Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority. 1998 AC 232.

Boynton S . Don't just sign here. Dent Protect Servicematters 2006; 4: 1–3.

Pearce v United Bristol Healthcare NHS Trust 1999. 48 BMLR 118.

Chester v Afshar 2004. UKHL 41.

Brands W G . The standard for the duty to inform patients about risks: from the responsible dentist to the reasonable patient. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 207–210.

General Dental Council. Standards for dental professionals. London: General Dental Council, 2005. http://www.gdc-uk.org/NR/rdonlyres/ FFD61DA5-A09E-4B38-8FFB-BA342E9F0AF4/16687/147158_Standards_Profs.pdf.

Department of Health. A Conscious Decision. A review of the use of general anaesthesia and conscious sedation in primary dental care. London: Department of Health, 2000. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/ PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4074702

Layton S, Korsen J . Informed consent in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a study of the value of written warnings. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 32: 34–36.

Langdon I J, Hardin R, Learmonth I D . Informed consent for total hip arthroplasty: does a written information sheet improve recall by patients? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2002; 84: 404–408.

Ernst S, Elliot T, Patel A et al. Consent to orthodontic treatment - is it working? Br Dent J 2007; 202: E25.

Mohamed Tahir M A, Mason C, Hind V . Informed consent: optimism versus reality. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 221–224.

Adewumi A, Hector M P, King J M . Children and informed consent: a study of children's perceptions and involvement in consent to dental treatment. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 256–259

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Michael Butterworth, Dental Protection senior cases consultant, for his helpful advice and clarification of law as it pertains to obtaining informed consent in all of the four nations which comprise the United Kingdom, as well as for validating the answers to the questions that were posed in the questionnaire; to Charlotte Emmett for her clarification of law pertaining to the Mental Capacity Act 2005; and to all of the consultants who participated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chate, R. An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Br Dent J 205, 665–673 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.1043

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.1043

This article is cited by

-

Consent and parental responsibility - the past, the present and the future

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

British Dental Journal (2008)