Abstract

Background:

In our clinical training program, which includes probable American Spinal Injury Association impairment scale (AIS) grade changes in the event of recovery, we have noticed some confounding results regarding the AIS grading in spinal cord injury (SCI) patient case examples who are expected to recover. We also observed an individual case that showed a conflict between AIS grade conversion and neurological changes in European Multicenter Study on Human Spinal Cord Injury study.

Study design:

The analysis of SCI case examples for the probable AIS grade changes in the event of recovery.

Objectives:

To demonstrate the possible problems with AIS classification in SCI cases involving presumed motor and sensory changes, and to clarify the possible causes of the inverse relationship between the motor/sensory changes and AIS conversion in certain conditions.

Setting:

Ankara, Turkey.

Methods:

We studied the case examples of reference from the 2011 revision of International Standards for the Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury.

Results:

We encountered the same unique problem of deteriorating AIS grades within the critical zones of conversion when presumed neurological improvement took place, and vice versa.

Conclusion:

When recovery occurs without observing any motor or sensory changes while taking only the AIS into account, it would be possible to make an incorrect conclusion. This is most likely an indication of a limitation of the AIS. To enlighten this paradox, the large amount of data in SCI databases should be reanalyzed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) assessments are the most frequently used instruments in spinal cord injury (SCI) clinical trials for measuring neurological damage and recovery.1, 2 The completeness of the SCI is graded by the ASIA impairment scale (AIS) with grades ranging from A to E, and the motor and sensory abilities of the patients are described using the ASIA motor and sensory scores.1, 2 Patients usually exhibit a combination of slight to robust motor and sensory changes at different levels, and these could contribute to or accompany the AIS conversion.3

Recovery is determined by conversions in the AIS and/or changes in the ASIA motor and sensory scores,2 while recovery rates are mostly based on conversion between the AIS grades.4 To better predict patient outcomes in recovering SCI patients, it is vital to understand whether the change in AIS is due to a change in the neurological level or due to a true neurological recovery. Consequently, the International Standards for the Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (International Standards for the Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI)), which were revised in 2011, were developed to have accurate communication between researchers.5, 6

Materials and Methods

In our clinical training program, which includes probable AIS grade changes in the event of recovery, we have noticed some confounding results regarding the AIS grading in SCI patient case examples who are expected to recover. Some cases showed worsening of AIS classification despite having actually neurological improvement in the event of presumed recovery, and vice versa. Subsequently, we performed a computerized literature search of PubMed from 1980 to December 2013. The keywords: ‘spinal cord injury’, ‘recovery’, ‘ASIA impairment scale’, ‘International standards for the neurological classification of spinal cord injury’ and the MeSH terms ‘spinal cord injuries’, ‘recovery of function’, ‘outcome scale’, ‘classification’ were used. We found one study by Spiess et al.3 that has reported a conflict between AIS grade conversion and neurological changes in European Multicenter Study on Human Spinal Cord Injury study. Therefore, we decided to show the limitation of AIS and to clarify the possible causes of inverse relationship between the motor/sensory changes and AIS conversion in certain conditions by using the case examples of reference for the 2011 revision of ISNCSCI,6 as it was developed to have accurate communication between researchers.

The International Standards examination were used to distinguish between a sensory incomplete and a motor incomplete (AIS B from C) injury, and between motor incomplete injuries (AIS C from D). The following definitions from the 2011 revision of ISNCSCI5 have been used to describe the unique problem of deteriorating AIS grades when presumed neurological improvement took place:

-

1)

Sensory level: The sensory level is the most caudal, intact dermatome for both pinprick and light touch sensation.

-

2)

Motor level: The motor level is determined by examining the key muscle functions within each of 10 myotomes and is defined by the lowest key muscle function that has a grade of at least 3 (on supine manual muscle testing), providing the key muscle functions represented by segments above that level are judged to be intact (graded as a 5).

-

3)

Neurological level of injury (NLI): The NLI refers to the most caudal segment of the cord with intact sensation and antigravity muscle function strength, provided that there is normal (intact) sensory and motor function rostrally.

-

4)

Distinguishing between a sensory incomplete versus a motor incomplete (AIS B from C) injury: The motor level on each side is used to differentiate AIS B from C injuries.

-

5)

Distinguishing between motor incomplete injuries (AIS C from D): The single neurological level (based on the proportion of key muscle functions with strength grade 3 or greater) is used to differentiate AIS C from D injuries.

Results

The analysis of SCI case example used in the reference article that differentiated AIS C from AIS D for the probable AIS grade changes in the event of recovery

The sensory level was C7 on the right and C6 on the left. In addition, the bilateral motor level was C8 and the single NLI was C6 with the presence of voluntary anal contraction. Additionally, 8 out of 16 testable key muscle functions received a grade of ⩾3 below the single NLI, resulting in the AIS D classification. In that example, if the case involved an acute injury and the patient only recovered normal sensory function at the C7 level on the left side, this would change the single NLI to C7, which would exclude the two key muscles that received a grade of ⩾3 at C7. That would leave only 6 of the 14 testable key muscle functions below the single NLI grade of ⩾3, meaning that this patient would ultimately be reclassified as an AIS C. In other words, worsening in classification status would occur despite a small degree of sensorial improvement. If we replicate cases with sensory levels above the motor level, then in patients with a slight improvement in sensory function, a common occurrence after spinal cord injuries at an early phase, a resulting change in the single NLI level would occur along with the exclusion of key muscles with a grade of ⩾3. Moreover, these muscles are always tested before any improvement in sensory function, which would result in a lower AIS grade. As the sensory or motor function may worsen in some cases in the early stages3 and changes in total sensory and motor scores could be in the same or opposite directions,7 we also considered the same example in reverse because a change in sensorial deterioration without a corresponding motor function change would lead to an improvement in the AIS grade (Table 1).

The analysis of SCI case example used in the reference article that differentiated AIS B from AIS C for the probable AIS grade changes in the event of recovery

When we try to distinguish between AIS B and AIS C, changes in sensory levels do not cause any problems as it is only possible to convert AIS B to AIS C if there is motor sparing more than three levels below the motor level on either side of the body in a patient with sensory sacral sparing along with no appearance of voluntary anal contraction. However, the case example in the reference article differentiated between AIS B and AIS C, indicating that the patient had a bilateral sensory level of C5, a bilateral motor level of C6, sensory sacral sparing without voluntary anal contraction and the following motor grades on the right side: C5=5, C6=4, C7=3, C8=1 and T1=1. If the deterioration at the C6 (a decrease in muscle strength from 4 to 2) is taken into account, this would immediately change the motor level from C6 to C5 on the right side. Since there was sparing more than three levels below this motor level (T1 muscle strength grade of 1), furthermore, the classification would improve from AIS B to AIS C in spite of the deterioration in motor function. If the same example is again reversed, the improvement in motor function from C5 to C6 would cause a corresponding deterioration in the AIS grade from C to B (Table 2).

Main findings

-

1)

When distinguishing between motor incomplete injuries (AIS C from D) in SCI cases with sensory levels above the motor level, in the event of a slight improvement in sensory function, a resulting change in the single NLI level would occur along with the exclusion of key muscles with a grade of ⩾3, which would result in a lower AIS grade; in other words, worsening in classification status would occur despite a small degree of sensorial improvement. In reverse, a sensorial deterioration without a corresponding motor function change, in which the sensory levels are below or at the same motor level, would lead to an improvement in the AIS grade as well. These inverse relationships are the examples of the problem concerning primarily the 5th ASIA definition mentioned in the method section.

-

2)

When distinguishing between a sensory incomplete versus a motor incomplete (AIS B from C) injury in SCI cases with sparing more than three levels below the motor level on either side of body (AIS C) without voluntary anal contraction, the motor improvement on corresponding side, a resulting change in the motor level would occur along with exclusion of sparing more than three levels below the motor level, which would result in the classification a deterioration from AIS C to AIS B in spite of the improvement in motor function. In reverse, motor deterioration, in which there is no sparing more than three levels below the motor level (AIS B), would cause a corresponding improvement in the AIS grade from B to C as well. These inverse relationships are the examples of the problem concerning primarily the 4th ASIA definition mentioned in the method section.

-

3)

All four AIS conversions described above might be in the ‘critical zone of conversion’ as they resulted from changes in a single motor or sensory level, and may reflect a problem concerning the ASIA definition rather than a true neurological recovery or deterioration.

Discussion

Although the AIS is regularly used to classify the severity of the initial SCI, the conversion rate of the AIS has also frequently been used as a measurement of neurological outcomes in clinical trials. The limitations of using the AIS as an instrument to measure outcomes have been discussed in previous studies and more recent studies have tended to use the AIS grade conversion and motor scores simultaneously, or they have proposed that detecting sensory and motor changes may require more sensitivity than measuring AIS grade conversion, especially when attempting to calculate therapeutic efficacy.8, 9

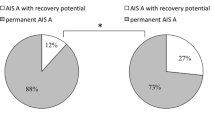

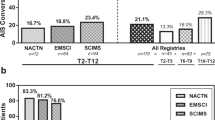

Many studies in the literature have focused on AIS conversion in SCI patients, but, to the best of our knowledge, only the study by Spiess et al.3 reported a conflict between AIS grade conversion and neurological changes. They reported only 1 out of a total of 90 patients, based on the data from the European Multicenter Study on Human Spinal Cord Injury, was converted from AIS B to AIS D owing to a change in motor level arising from sensorial deterioration without a gain in muscle score. However, the inverse relationship between the motor/sensory changes and AIS conversion was not the primary focus of their study. They also speculated that this paradox maybe reflect a problem concerning the ASIA definition or the assessor’s level of expertise.

After examining the case examples in the ISNCSI reference article, when recovery occurs without observing any motor or sensory changes while taking only the AIS conversion into account, we believe that it would be possible to make an incorrect conclusion. Furthermore, this is most likely another indication of a limitation of the AIS. In a clinical setting, when reporting a patient’s progress, it would also be problematic to express, for example, that a patient’s sensory/motor scores have improved but that the AIS had gone backward, or vice versa. For this reason, these findings may guide clinicians regarding prognosis and treatment decisions, including the consideration of critical conversion zones as a discrepancy factor when grading AIS. In our opinion, ‘the ASIA Standards’ is a result of an extensive and evolving work from experts in SCI research. The ASIA Standards has been revised several times in the past and currently it still is the best SCI classifications system we have. Other widely accepted SCI measurement tools, such as the Modified Benzel classification, might also be prone to such problems. None of them could provide a global measure of all cord functions. It would be very difficult to classify and assess such a complex continuum that evolves over time, in a comprehensible classification system that provides researchers the opportunity to coordinate properly.

Conclusion

Results of this analysis confirm that the AIS classification can yield clinically illogical results, regarding the neurological level change contributing AIS grade changes that occur within the critical conversion zones. When recovery occurs without observing any motor or sensory changes while taking only the AIS conversion into account, we believe that it would be possible to make an incorrect conclusion. Furthermore, this is most likely another indication of a limitation of the AIS. In addition, we also believe that the large amount of SCI data in databases such as the Sygen and European Multicenter Study on Human Spinal Cord Injury should be reanalyzed, as a significant amount of the reported cases of AIS deterioration have originated from them.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

Change history

05 September 2014

This article has been corrected since Advance Online Publication and a corrigendum is also printed in this issue.

References

Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Tuszynski MH, Ditunno JF et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 206–221.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 190–205.

Spiess MR, Müller RM, Rupp R, Schuld C, EM-SCI Study Group, van Hedel HJ . Conversion in ASIA impairment scale during the first year after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2009; 26: 2027–2036.

Lammertse D, Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Rask C et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial design. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 232–242.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

Kirshblum SC, Waring W, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Johansen M, Schmidt-Read M et al. Reference for the 2011 revision of the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 547–554.

Zariffa J, Kramer JLK, Fawcett JW, Lammertse DP, Blight AR, Guest J et al. Characterization of neurological recovery following traumatic sensorimotor complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 463–471.

Buehner JJ, Forrest GF, Schmidt-Read M, White S, Tansey K, Basso DM . Relationship between ASIA examination and functional outcomes in the neuro recovery network locomotor training program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 1530–1540.

Steeves JD, Kramer JK, Fawcett W, Cragg J, Lammertse DP, Blight AR . Extent of spontaneous motor recovery after traumatic cervical sensorimotor complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 257–265.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gündoğdu, İ., Akyüz, M., Öztürk, E. et al. Can spinal cord injury patients show a worsening in ASIA impairment scale classification despite actually having neurological improvement? The limitation of ASIA Impairment Scale Classification. Spinal Cord 52, 667–670 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.89

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.89

This article is cited by

-

Wavelet coherence as a measure of trunk stabilizer muscle activation in wheelchair fencers

BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation (2021)

-

A prediction model of functional outcome at 6 months using clinical findings of a person with traumatic spinal cord injury at 1 month after injury

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

A pilot study on temporal changes in IL-1β and TNF-α serum levels after spinal cord injury: the serum level of TNF-α in acute SCI patients as a possible marker for neurological remission

Spinal Cord (2015)