Abstract

Objectives:

To systematically develop an evidence-informed leisure time physical activity (LTPA) resource for adults with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Canada.

Methods:

The Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II protocol was used to develop a toolkit to teach and encourage adults with SCI how to make smart and informed choices about being physically active. A multidisciplinary expert panel appraised the evidence and generated specific recommendations for the content of the toolkit. Pilot testing was conducted to refine the toolkit's presentation.

Results:

Recommendations emanating from the consultation process were that the toolkit be a brief, evidence-based resource that contains images of adults with tetraplegia and paraplegia, and links to more detailed online information. The content of the toolkit should include the physical activity guidelines (PAGs) for adults with SCI, activities tailored to manual and power chair users, the benefits of LTPA, and strategies to overcome common LTPA barriers for adults with SCI. The inclusion of action plans and safety tips was also recommended.

Conclusion:

These recommendations have resulted in the development of an evidence-informed LTPA resource to assist adults with SCI in meeting the PAGs. This toolkit will have important implications for consumers, health care professionals and policy makers for encouraging LTPA in the SCI community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leisure time physical activity (LTPA) improves fitness and well-being in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI),1, 2 yet 50% of this population participate in no LTPA whatsoever.3 Lack of knowledge and resources are two barriers that significantly influence LTPA participation.2 Addressing such barriers would be an important and necessary step towards improving LTPA levels among the SCI population.

In 2011, the first-ever physical activity guidelines (PAGs) for adults with SCI were published internationally.4 These guidelines were developed, in consultation with a multidisciplinary expert panel, using a systematic review and quality appraisal (the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II)5, 6, 7 of research examining the effects of exercise on the physical fitness of people with SCI.1 The PAGs state that healthy adults with SCI should engage in ⩾20 min of moderate to heavy aerobic activity twice/week, and strengthening exercises two times/week.4

Supplementing the PAGs with evidence-informed resources that teach adults with SCI how to achieve these guidelines is essential for effective behavior change.8 The current paper describes the systematic process used to develop an evidence-informed, SCI-specific LTPA resource (‘SCI Get Fit Toolkit’). The process involved a multidisciplinary expert panel and used the AGREE II protocol5, 6, 7 to formulate the toolkit content and recommendations for dissemination. Although the AGREE II is most often used to develop evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, recent work has shown that the protocol can also be effectively applied to health promotion practices.9 Our work extends this research by demonstrating the translation of empirical evidence into a practical LTPA resource for the SCI community.

Methods and Results

Overview

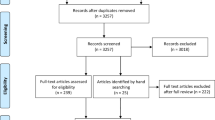

The 23-item AGREE II instrument5, 6, 7 was used as a framework to develop the toolkit. Similar to previous research,9 the wording of the items was modified to fit a health promotion practice rather than a clinical practice guideline (see Table 1). Figure 1 provides a summary of the events leading to the development of the toolkit. All applicable institutional regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Scope and purpose

The objective, practical questions, target population and end users were determined by the project leads (KAN, KMG) a priori based on previous systematic reviews1, 2 and pilot work.10 An expert panel reviewed and agreed with these established parameters.

-

Objective: to develop an evidence-informed resource that teaches and encourages adults with SCI how to make smart and informed choices about being physically active.

-

Practical questions: how can the PAGs be communicated to adults with SCI? What type of resource will motivate adults with SCI to engage in LTPA?

-

Target population: healthy men and women with traumatic or non-traumatic chronic SCI (ages 18–64),4 manual and power chair users, and adults not meeting the PAGs.

-

End users: adults with SCI, community partners, practitioners, rehabilitation centers, Ministry of Health (Federal and Provincial), Canadian Parks and Recreation Association, Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology, Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and other fitness centers.

Stakeholder involvement

Stakeholders including consumers with SCI, researchers, health care practitioners and community service providers were involved in: (a) the formative research conducted before developing the toolkit, (b) the development of the formal recommendations for the toolkit content and format, and (c) a review and feedback process. Specific details of their involvement are highlighted below.

Toolkit development process

This section provides a detailed description of the 4-phased process used to develop the toolkit. Table 1 relates each step in this process to the modified AGREE II items.

Phase 1: formative research

The views and preferences of the target population were previously sought in a needs assessment among 78 adults with SCI.10 Overall, participants preferred the content of the resource to provide clear activity definitions, home-based and seasonal activity examples, the benefits of physical activity and information tailored to injury groups. In terms of format preferences, participants preferred a booklet and/or an interactive website, text and picture combination, photographs, bright colors, simple messages, a pull-out calendar, quick facts and several pages of information.

Phase 2: review of evidence-base

The evidence-base providing the foundation for the toolkit included formative research,10 publication of the development of the SCI PAGs,4 the SCI PAGs, a validated, SCI-specific intensity chart,11 a summary of the Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence systematic review on physical activity and SCI,2 and abstracts of the two largest randomized controlled trials in the area of SCI and LTPA behavior change.12, 13

A purposive, rather than systematic, search strategy was used to gather the evidence-base to inform the recommendations due to the limited experimental research on exercise and health/fitness, and LTPA determinants and interventions in the SCI population.1, 2 The criteria for selecting the evidence-base was that the research: (1) be specific to SCI, and (2) focus on the benefits of and barriers to LTPA, LTPA determinants and preferences, and interventions for promoting LTPA. The Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence review2 provides the most rigorous evidence on the aforementioned topics; therefore, the recommendations were specifically directed towards the evidence-base emanating from this review.

The strengths of the research evidence include: the sufficient experimental research to support the fitness benefits of engaging in the recommended PAGs in persons with chronic SCI,1 the robustness of the relationship between LTPA-depressive symptomatology and LTPA-quality of life,14 the consistent occurrence of intrapersonal, systemic and expertise-related barriers to LTPA,15 the population-based research investigating determinants of LTPA participation3 and activity preferences,16 and the experimental evidence to support the use of theory-based behavior change strategies for increasing LTPA.12, 13 The limitations include: insufficient evidence on the fitness benefits of exercise for acute SCI, sample heterogeneity, inadequate control groups, insufficient evidence on the health benefits of the SCI PAGs and participant selection bias.1, 2, 4 The recommendations were not externally reviewed by experts outside of the panel. However, individual interviews and focus groups were conducted with consumers with SCI to review the recommendations and content of the toolkit before the release of its final version. Refer to Phase 4 for a description of this consumer review process.

Phase 3: development of evidence-informed content and format recommendations

A multidisciplinary panel of 10 leading researchers and community service providers in the areas of SCI, LTPA, medicine (physiatry), sport, education and knowledge translation appraised the evidence and generated recommendations for the toolkit. Table 2 lists panel members, along with their expertise, affiliations and roles.

A multistep process was followed to formulate the recommendations. Before the meeting, the panel was provided the evidence-base to review. At the beginning of the meeting, a summary of the project’s objectives and overview of the evidence was presented to the panel. On the basis of areas of expertise, panel members then participated in two of the four, 90-minute work group sessions (refer to Table 2), where they developed specific content and format recommendations using the evidence reviewed before the meeting (see Table 3). A debriefing meeting was then held at the end of the first day between the project leads and one expert panel member (AEL) to summarize these recommendations. On the second day, a facilitated discussion was held to review and revise the recommendations.

The expert panel agreed that the overarching message should be, ‘physical activity is easy and fun to do!’ and in French – ‘C’est façile, alley-z!’. Table 3 summarizes the link between each of the six overarching recommendations and the supporting evidence. Although the need among consumers for a longer, paper copy version of the toolkit was recognized, the panel as a whole felt it would be more feasible to develop a toolkit similar in length to the physical activity guides that have been previously developed for the Canadian adult able-bodied population.17 To accommodate the interests of the SCI community, it was agreed that more detailed ‘how to' information would be made available on a toolkit section of the SCI Action Canada website—the organization responsible for hosting the online version of the toolkit.

The knowledge translation plan and resource implications for disseminating the toolkit were also discussed. Suggested methods to disseminate the toolkit included mailing paper copies to partner organizations; creating an online version; posting links on social media; using mass media for broad promotion of the toolkit; and obtaining testimonials from various end users. It was unanimously agreed that it would not be feasible to update the paper copy of the toolkit regularly. Rather, the toolkit would be made available on the SCI Action Canada website, with updates made according to the availability of resources.

When discussing how to ensure that the toolkit is implemented as a routine part of practice, the panel recognized the importance of having SCI Action Canada staff and researchers work with practitioners to ensure the toolkit is strongly linked with a credible source for LTPA information within the SCI community. One expert panel member suggested that the SCI Action Canada logo be visible on the front page of the toolkit so that practitioners can readily distinguish the credibility of the information. The anticipated resource implications of disseminating the toolkit were: printing of paper copies; management of the SCI Action Canada website; availability of service providers for sending members updates; and a greater demand on SCI Action Canada for additional resources, staff, and researchers. Strategies for evaluating and monitoring the uptake of the toolkit included monitoring the distribution of paper copies and using Google analytics to assess online usability of the toolkit. There is no current funding for monitoring the uptake of the toolkit.

Following the meeting, a detailed summary of the recommendations was emailed to the expert panel (one of whom was unable to attend the meeting) to review and revise.

Phase 4: toolkit development

The development of the toolkit proceeded using the panel’s content and format recommendations outlined in Table 3 as a framework. A technical writer worked alongside the first author to ensure that the content had clear and concise descriptions, coherent examples of activities and coping strategies and appropriate language for the target audience. A professional photographer and graphic designer were also hired to ensure that the images and formatting met the specific criteria outlined in the panel’s recommendations.

To assess whether the content and format recommendations had been adequately addressed in the toolkit, members of the expert panel completed a 20-item questionnaire. Table 4 provides a summary of the panel’s feedback. Responses were favorable on all items (M=6.2 on a 7-point scale), indicating consistency between the recommendations and the content and overall presentation of the toolkit. One suggestion given by the panel was to include more images of persons with tetraplegia.

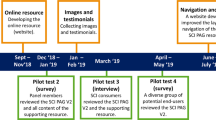

Pilot work was also conducted with SCI consumers to assess the clarity of the toolkit for the target audience. Given future plans for disseminating the toolkit to rehabilitation centers, it was important to include both community-dwelling consumers and inpatients for this pilot work. Table 5 summarizes the feedback obtained from consumers and the modifications subsequently made to the toolkit. Briefly, the consumer sample (N=15; 67% male; Mage=53.0 years±13.4) included persons with tetraplegia (47%) and paraplegia (47%), as well as manual (80%) and power chair users (7%), and those who used a walker (13%) as their primary mode of mobility. The majority were community-dwelling consumers (80%), while the remaining were acute inpatients (20%). Six consumers participated in an interview to discuss the content of the toolkit, while the remaining nine consumers participated in either a 30–45 min semistructured focus group (n=4) or telephone interview (n=5) to provide feedback on the full version of the toolkit (see Figure 1). Similar to the expert panel, consumers found the content to be appropriate and the images to be encouraging for assisting adults with SCI in achieving the PAGs. Consumers’ concerns were related to formatting (for example, font size, length), the appropriateness of activities and images for adults with higher-level injuries and/or older population and barriers (for example, transportation, transferring) to some of the suggested activities. The final version of the toolkit is presented in Figure 2.

Discussion

Using an internationally accepted, rigorous systematic consultation process,5, 6, 7 our group was able to develop the first-ever, evidence-informed resource to assist adults with SCI in achieving the PAGs.4 The expert panel’s recommendations were fundamental for guiding the development and future dissemination of the toolkit. Our toolkit is anticipated to have important implications for a variety of stakeholders. For consumers with SCI, the toolkit will increase awareness and knowledge of the SCI PAGs and behavioral strategies for engaging in LTPA. For health care professionals, the toolkit provides an evidence-based resource that can be implemented into routine practice to facilitate discussion of LTPA and exercise prescription among clients with SCI. For policy makers, the toolkit can be used as an advocacy tool to inform policies on improving LTPA opportunities for persons with SCI, such as enhancing access to and accessibility of fitness and recreational facilities.

Dissemination barriers and facilitators

For consumers with SCI, the main barrier is reaching individuals not linked to organizations that would use health care services. One facilitator considered by the panel was to create broad awareness of the toolkit via mass media. For health care professionals and service providers, issues were raised relating to time constraints, competing service demands to provide clients with a variety of health-related information and uncertainty regarding the optimal time to introduce the toolkit in acute practice. The facilitators identified to overcome these barriers included: consumer education, advocacy for the use of the toolkit in practice by respected health care champions and publishing information about the toolkit in medical journals and magazines. The panel also advised that a fact sheet be developed that describes how to use the toolkit in acute practice.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strengths of this work include the systematic process5, 6, 7 used to develop the recommendations, the eclectic background of our panel, which included experts from a variety of disciplines, institutions and organizations, and the participatory methodology used to develop the toolkit. SCI consumers from the community and rehabilitation, as well as the expert panel members, were given the opportunity to provide feedback on the toolkit over the course of its development. This type of community-vetted approach is fundamental to developing resources that are of interest to the target audience and sustainable within the community.18 To our knowledge, there is no other LTPA resource available for the SCI community that is both evidence-based and developed in consultation with consumers. The integrated research-knowledge mobilization approach that was used to develop the toolkit provides a template for developing effective health promotion materials in other populations.

Next steps

Panel members will work with community partners to disseminate the toolkit across Canada. The project leads are currently working towards a French translation of the toolkit to enhance the reach of the toolkit across Canada. Additional funding will be sought for large-scale dissemination of the toolkit to rehabilitation centers and health care professionals. Such funding will provide the opportunity to evaluate the population-level impact of the toolkit on the awareness of the PAGs, the percentage of adults with SCI meeting the PAGs and monitoring changes in routine practice.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Hicks AL, Martin Ginis KA, Pelletier CA, Ditor DS, Foulon B, Wolfe DL . The effects of exercise training on physical capacity, strength, body composition and functional performance among adults with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 1103–1127.

Wolfe DL, Martin Ginis KA, Latimer AE, Foulon BL, Eng JJ, Hicks AL et al. Physical activity and SCI. In: Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF and Hsieh JTC et al. (eds). Spinal Cord Injury, 2010 Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 3.0.

Martin Ginis KA, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Buchholz AC, Bray SR, Craven C et al. Leisure-time physical activity in a population-based sample of people with spinal cord injury Part I: demographic and injury-related correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 722–728.

Martin Ginis KA, Hicks AL, Latimer AE, Warburton DER, Bourne C, Ditor DS et al. The development of evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 1088–1096.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman G, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010; 182: E839–E842.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman G, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63: 1308–1311.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman G, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Prev Med 2010; 51: 421–424.

Brawley LR, Latimer AE . Physical activity guides for Canadians: messaging strategies, realistic expectations for change, and evaluation. Can J Public Health 2007; 98: S170–S184.

Latimer-Cheung AE, Tomasone JR, Rhodes RE, Kho M, Nausti G, Gainforth HL et al. Developing evidence-based messages for translating physical activity guidelines into practice. Ann Behav Med 2012; 43: S93.

Foulon BL, Lemay V, Ainsworth V, Martin Ginis KA . Enhancing the uptake of physical activity guidelines: a needs survey of adults with spinal cord injury and health care professionals. Adapt Phys Activ Q 2012; 29: 329–345.

Martin Ginis KA, Latimer AE, Hicks AL, Craven BC . Development and evaluation of an activity measure for people with spinal cord injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005; 37: 1099–1111.

Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Martin Ginis KA, Latimer AE . Turning intentions into action: Combined effects of action and coping planning on leisure-time physical activity and coping self-efficacy in persons living with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 2003–2011.

Latimer AE, Martin Ginis KA, Arbour KP . The efficacy of an implementation intention intervention on promoting physical activity among individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Rehabil Psychol 2006; 51: 273–280.

Hicks AL, Martin KA, Ditor DS, Latimer AE, Craven C, Bugaresti J et al. Long-term exercise training in persons with spinal cord injury: effects on strength, arm ergometry performance and psychological well-being. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 34–43.

Scelza WM, Kalpakjian CZ, Zemper ED, Tate DG . Perceived barriers to exercise in people with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 84: 576–583.

Martin Ginis KA, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Latimer AE, Buchholz AC, Bray SR, Craven C et al. Leisure-time physical activity in a population-based sample of people with spinal cord injury Part II: activity types, intensities, and durations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 729–733.

Health Canada and the Canadian Society of for Exercise Physiology 1998 Canada's physical activity guide for healthy active living. Cat. no. H39-429/1998-1E. Health Canada. Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Minkler M . Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health 2005; 82: ii3–ii12.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the consultation meeting and the development and dissemination of the toolkit were provided by the Rick Hansen Institute, the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, and the Canadian Paralympic Committee. Support for some of the research and knowledge translation activities was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K., Martin Ginis, K., Latimer-Cheung, A. et al. Development of an evidence-informed leisure time physical activity resource for adults with spinal cord injury: the SCI Get Fit Toolkit. Spinal Cord 51, 491–500 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Developing a consensus on the core educational content to be acquired by people with spinal cord injuries during rehabilitation: findings from a Delphi study followed by a Consensus Conference

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Co-development of a physiotherapist-delivered physical activity intervention for adults with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Translating the international scientific spinal cord injury exercise guidelines into community and clinical practice guidelines: a Canadian evidence-informed resource

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

A randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of the SCI Get Fit Toolkit on leisure-time physical activity behaviour and social-cognitive processes in adults with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2017)

-

Active Living Leaders Training Program for adults with spinal cord injury: a pilot study

Spinal Cord (2016)