Abstract

Study design:

Qualitative study.

Objective:

To determine categories of coping the first year after injury used by 24 young adults who sustained a spinal cord injury (SCI) during adolescence (11–15 years).

Setting:

Sweden.

Methods:

Content analysis using the existing theories of coping as a framework, including the instrument BriefCOPE—a deductive category application. The analysis looked critically at comments in the interviews that reflected attempts to cope with the injury during the first post-injury year.

Results:

All 14 of the categories of coping described by the BriefCOPE were included in the interviews at least once, except ‘self-blame’, which was not used by any interviewee. In addition to the predefined categories of the BriefCOPE, three new coping categories emerged from the interviews: fighting spirit, downward comparison and helping others.

Conclusions:

Adolescents who sustain SCIs use a variety of strategies to help them to cope with the consequences of the injury. Many of these coping strategies are similar to those used by others facing stresses, but it is instructive to hear, in their own words, how young adults recall the coping strategies they used as adolescents when they were injured and also how they conceptualized the process of coping. This information can be useful in helping future patients.

Sponsorship:

The study was supported by the Promobilia foundation and the Norrbacka–Eugenia foundation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adjustment to a spinal cord injury (SCI) has been identified as important for achieving long-term goals, such as gaining employment and participation in the community.1 Coping is the process of attempting to manage the demands created by stressful events that are appraised as taxing or exceeding a person's resources.2 These efforts seek to manage, master, tolerate, reduce or minimize the demands of a stressful environment.3 Lazarus and Folkman4 believe that each individual represents a unique combination of individual and environmental factors that interact, which cause the person to appraise the situation, appraise the coping resources that are available to him or her and employ a repertoire of coping behaviors. Coping strategies have been found to be relatively stable over time in adults5 and studies have suggested that individuals can benefit by learning coping strategies.6 It has been reported that adults with SCI manage the consequences of their disability without significant levels of psychopathology, but the coping strategies used are critical for this adjustment.7

The coping strategies used by typically developing adolescents in various settings and with a range of life problems is comprehensively described by Frydenberg.8 She reports that there is a breadth of general research on coping with chronic illness in adolescence, but few studies have investigated the specific coping strategies used by this group of adolescents.9 There are reports from the United States about the coping strategies used by adults who sustained SCI during childhood or adolescence.10, 11 These investigators used the BriefCOPE survey instrument12 and found several coping strategies, such as seeking emotional support, acceptance and religion, that were associated with greater life satisfaction. High adult life satisfaction was negatively associated with the substance use.10, 11

The aim of the present study is to determine the coping strategies used in the first year after injury by young adults in Sweden who had sustained SCI during adolescence. In this case, the individuals were interviewed about the psychosocial factors that had promoted their readjustment during the first year after injury.13 The hypothesis is that their spontaneous comments about coping with SCI can be categorized into strategies of coping similar to those identified in previous studies of coping with SCI.

Materials and methods

A qualitative research approach was chosen for this study in order to explore and ultimately to gain insights of psychological aspects during rehabilitation and early readjustment by focusing on the injured person's own recollections. The goal of this approach is to enable the person to give more in-depth, comprehensive information in their own words rather than using responses that are predefined.14

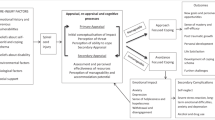

The method of content analysis was chosen using the existing theories of coping as a framework. This is described by Mayring15, 16 as deductive category application (Figure 1).

For the analysis in this study, the instrument Brief COPE12 was used as a framework to detect coping strategies in the interviews. The instrument with its coping strategies has been assessed in a previous study and have been found relevant to the studied population.10

Although we used the preexisting categories of Brief COPE,12 the categories were considered to be preliminary and not exhaustive. Any differences or unanticipated kinds of coping that emerged from the interviews were considered important because they had the potential to lead to new categories of coping and/or to help refine or modify the original categories.

Interviewees

Data from the Swedish population registers, county habilitation centers, as well as from several informal sources, were used to identify all persons who had sustained a SCI during the years 1985–1996, at the age of 0–15 years. The demographics and the subject identification procedure have been reported previously.17, 18

A total of 37 persons who survived at least 2 years after injury were thus identified. This group comprised the total prevalence population of pediatric-onset SCI, aged 0–15 years, in Sweden during the time surveyed. The present study comprises a subset of 28 persons, who were adolescents, aged 11–15 years, at the time of injury. The duration of adolescence is defined by the World Health Organization from age 10–19 years.19

One male was excluded because of severe acquired congenital cognitive impairment, one male had died and two males declined participation (aged 14 and 15, respectively, at the time of injury). Clinically, there were no indications that they would differ from the rest of the group. Thus, 24 persons were included in the study.

Further descriptors are summarized in Table 1.

Data collection

Interviews lasted for 60–90 min, and were conducted by one of the authors (MA), at the venue of choice of the interviewee, typically at his/her home. The recorded interviews were later transcribed verbatim. The interviews were performed 4–15 years after injury (mean 10 years) during 2002–2004.

The interview was based on three questions: (1) What factors facilitated your rehabilitation and early readjustment? (2) What factors impeded your rehabilitation and early readjustment? (3) What do you suggest for improvements in system of care? These questions initiated a dialogue that was expanded by use of further open-ended questions, for example: What do you mean by that?; Can you describe a little bit more about this?; or What did you think about that?13

Data analysis

For this study all interview transcripts were read by MA, highlighting all text that on the first impression appeared to represent coping. Coping was conceptualized as ‘a process by which the persons used cognitions and actions to manage the stressors associated with the injury’.20

The next step was to code all the highlighted passages in the transcripts using the predetermined codes and their definitions described in the instrument BriefCOPE.12 Any text that could not be categorized with the initial coding scheme was given a new code.

BriefCOPE12 consists of 14 different coping strategies: self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, behavioral disengagement, venting, use of instrumental support, positive reframing, self-blame, planning, humor, acceptance, religion (a definition of each coping strategy is included in the instrument, Table 2). In order to further clarify categorical content, verbatim citations illustrative of respective subcategory were selected. They are presented throughout the ‘Results’ section of this paper; the gender and the age at injury are also noted.

Data validation

Coping strategies thus identified were subsequently subjected to a validation and verification process by a consensus strategy, whereby the authors discussed and reexamined coding discrepancies in a further effort to reach consistency. Further, an expert of qualitative research reread all the quotes and confirmed our verifications.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden. Interviewees gave informed consent and were granted confidentiality. Individual interviewees would not be identifiable in the subsequent report. Interviewees were informed that they could terminate their participation in the study at any time. The interviewer (MA) was not involved in the medical care of any interviewee at any time.

Results

In all the interviews, the interviewees described the use of coping strategies. All 14 of the categories of coping described by the BriefCOPE were included in the interviews at least once, except ‘self-blame’, which was not used by any interviewee. In addition, three new categories emerged from the interviews that we defined as coping, but were not possible to include in the predefined categories of the BriefCOPE: ‘fighting spirit’ (n=15), ‘downward comparison’ (n=9) and ‘helping others’ (n=7).

‘Fighting spirit’, or use of their own abilities to overcome obstacles, could be exemplified in the transcripts as: ‘To avoid obstacles was important for me and it still is. If I want to do something, I’ll do it. If I want to go through Europe with trains or going by boats in Greece, I will do it. If I have decided it will work then it works’ (female, 14 years at the time of injury).

Another new category that emerged was ‘downward comparison’. This internal process by using comparison between themselves and other persons who were ‘worse off’ helped some of the interviewees to cope with their own injury were found: ‘I realized that many were worse than me. Some couldn’t use their arms and one person needed a ventilator the rest of his life. Then I thought that my injury is not so bad, I can surely learn to live with it. I saw it in a different light’ (female, 13 years at the time of injury). Similar to this, but more of an action than a thought, was another coping strategy named ‘helping others’. Most of the interviewees who recalled using ‘downward comparison’ (n=9) also felt that helping others made them feel better (n=7): ‘I like to help others, listen to friendś trouble. I like when others feel good, then I forget myself’ (female, 13 years at the time of injury);

The different kinds of strategies varied among the interviewees and also the number of the strategies that were used. Of the 17 identified coping categories that were found in the interviews, on average 8 were used by each interviewee (range 5–15). The frequency with which different coping strategies were used is shown in Table 2.

All of the interviewees mentioned using the coping categories ‘emotional support’ and ‘instrumental support’.

Use of ‘emotional support’ (n=24) was obvious in the interviews: ‘One important thing is to stay in touch with your friends. I managed to get back to my friends and stay friends but many don’t manage that. I was lucky’ (female, 14 years at the time of injury). Also, the family was mentioned by most of the interviewees (n=21) as important for emotional support. There were also recollections of other persons providing emotional support, including teachers, role models, romantic partners and other important adults, as this example about a sports coach: ‘He came nearly every day. He was totally amazing. Every day he brought along some of my teammates. He was always positive. // we’re still in touch’ (male, 14 years at the time of injury). Emotional support could also be provided by the staff in some recollections. Some interviewees had still close contact with persons of the staff. A few regarded the night staff as the most important persons they met during their hospitalization and with whom they could exchange thoughts during the night.

The staff, together with parents, other important adults and role models (that is, other persons with SCI) were mentioned by the interviewees as having provided help and advice that is, ‘instrumental support’ (n=24). To meet other persons with SCI was regarded an important help in the new situation either through camps or by more individual contact: ‘You should have the right to have a mentor, I didn’t. You need someone that you can talk to and especially about questions dealing with sex. It feels is really weird if you have to ask your mother’ (female, 13 years at the time of injury).

The next most frequently used category of coping was ‘active coping’ (n=21). Several interviewees recalled taking full control of their medications and other procedures in their treatment, but mostly active coping was explained like: ‘If it looks really dark, the only thing that really works is to train. Then you are able to see your goals. Otherwise it becomes too heavy’ (female, 11 years at the time of injury).

Outwardly directed anger and aggression were common and found in the interviews, which could be referred to the category of ‘venting’ (n=13): ‘I threw things. When I saw that nobody was around, I threw things’ (female, 14 years at the time of injury). The anger was often directed towards parents and staff, and some of the interviewees still had a bad conscience about their behavior many years later.

The importance of training occurred frequently in the category of ‘active coping’, but some citations concerning training belonged more to another category of coping, ‘self-distraction’ (n=12) as in the following example: ‘I think you must be active and become activated as much as possible. Then you don’t have time to sit and ponder how bloody disgusting things are. It should be full speed. You should never have time to ponder; it should be activities all the time so you don’t think about it. Instead you should try to deliver something. Maybe this doesn’t work for everyone, but for me it worked pretty damn good anyway’ (male, 14 years at the time of injury). ‘Self-distraction’ also included daydreaming and some interviewees became absorbed by different kinds of interests or hobbies to make themselves forget about the injury. One interviewee explained it like this: ‘I just read and read. I read everything I came over…’ (female, 13 years at the time of injury).

To see goals and to come up with a strategy was sorted into the category of ‘planning’ (n=11), as in the following example: ‘There is a light in the tunnel when you have goals. I will try to be as good as xx(role model), that person is the best evidence that it will work’ (female, 11 years at the time of injury).

During periods of their rehabilitations there were recollections of giving up trying to deal with the new situation; ‘behavioral disengagement’ (n=11):

‘I switched off, I barely spoke with my parents, who were there every day. They were somewhere and I was, like, somewhere else. I had problems with my friends who came too. I was shut off. The only people I spoke with were the staff and the other patients’ (female, 13 years at the time of injury).

Some of the interviewees (n=11) remembered periods of ‘denial’ of what had happened, especially close to the time of the injury. However, there were two interviewees who still denied the situation at the time of the interview many years post injury: ‘I have been thinking all the time that this will pass’ (female, 11 years at the time of injury).

In all, 8 out of the 24 interviewees mentioned using ‘positive reframing’, seeing something positive in what had happened. There were many examples of being stronger, more mature, competent and knowledgeable. One girl explained positive reframing as the following: ‘I usually think—if this hadn’t happened I wouldn’t be the person I am today. And given that I am happy with who I am I can’t regret what actually happened’ (female, 13 years at the time of injury).

The use of ‘humor’ (n=8) was mentioned, in some cases, as being up to mischief with the staff, but mostly when telling about the injury in a humoristic way in their interviews: ‘… and the road turned, but I didn’t.’ (male, 14 years at the time of injury).

Five persons mentioned use of ‘acceptance’ during the interview. The use of alcohol (‘substance use’) was mentioned by three interviewees as a way of coping. Two of the twenty-four interviewees recalled using ‘religion’ as a strategy of coping, and one girl (13 years at the time of injury) recalled that she and her friends in a religious group had prayed together for her.

Discussion

The results of this study show that ‘emotional support’, provided by family, friends and other important adults, and ‘instrumental support’, receiving help from others, were mentioned by all interviewees and recalled as important for adjustment. This result is in accordance with previous research showing how adolescents typically cope in various settings with a range of life problems.8, 21

It is therefore of utmost importance for professionals to encourage families and friends to support the adolescents and also to encourage the adolescent to seek out both social and instrumental support.21, 22 However, it should be noted that social support does not mean social reliance. Elfstrom et al,23 defines social reliance as a tendency towards dependent behavior, which was found to be correlated with helplessness and intrusion in adults with SCI.

‘Instrumental support’ was recalled as very important, especially with respect to the need of mentorship and role models. The key function of role models in the rehabilitation of patients with SCI, both in promoting an active lifestyle and in helping to establish a new identity, has been proposed previously.13, 24, 25, 26 However, the evidence that does exist is mostly anecdotal and future evaluation, and research in this field is needed.

The category of ‘self-blame’ that was included in the questionnaire BriefCOPE, was not recalled in the interviews. This is interesting, as self-blame is often regarded as a maladaptive coping strategy. According to Frydenberg,8 self-blame and keeping to self are of the most concern and need to be reduced by preventive measures.

It is difficult to speculate why self-blame was not used by any of the interviewees. Most of them were victims in traffic or in sports and very few of the injuries were caused by the adolescents themselves. We could also raise the question if this is a culture difference or if this is a difference due to age and need more research.

On the other hand, the use of ‘fighting spirit’, ‘downward comparison’ and ‘helping others’ were recalled as important categories of coping in our study, but not found in the questionnaire BriefCOPE. There are numerous studies documenting social comparison with respect to coping27, 28, 29, 30 and especially downward contrast (a positive response to realizing others were worse-off) was reported as particularly related to constructive coping in persons with SCI.27 ‘Fighting spirit’ (that is, efforts to behave independently)23 requires that the individuals think they can take control of the situation themselves and ‘fight back’ to make their lives better. This is similar to the concept of ‘Internal locus of control’ that has been mentioned in the coping literature.1, 31 Individuals with an internal LOC have the expectancy that their behaviors will affect outcome and this is perceived as an important strategy of coping among adults with SCI. Also in a recent article,32 Fighting spirit was the only coping strategy that was significantly related to adjustment in newly injured adults with SCI.

Sweden is known to be highly secular, with only 10% of the overall population going regularly to church, whereas the United States has a highly religious population with 53% attending church.33 This cultural difference between the countries is reflected in the interviews, as only two persons recalled use of ‘religion’ as a coping strategy, whereas a study from the Shriners Hospital for Children11 reported that over half of the participants endorsed importance of religion and the use of spiritual among adults with pediatric-onset SCI using the questionnaire BriefCOPE. This is an important issue to consider when using and interpreting results from questionnaires between different countries and cultures. ‘Acceptance’ was not frequently mentioned by the interviewees in contrast to the research from the Shriners Hospitals for Children.10 The explanation for this cultural difference is not possible to explain by the result of this study, but one girl expressed it as: ‘I don’t accept what has happened to me but I have learned to live with it’. Instead, many of the interviewees recalled use of ‘active coping’ as very important. However, we note that individuals use activities, such as training, as different styles of coping. Some saw training as a coping strategy that would bring them closer to a goal, whereas others saw training as a type of distraction, almost a way of keeping their minds off their injury. The first may reflect a more internal locus of control or the belief that the individuals may actually make a difference in their situation.

Apart from the inherent and inevitable limitations of a qualitative methodology, the most obvious limitation is the recall bias imposed by the years gone by from injury to the interview. In this study, most of the interviewees were young adults at the time of the interview, but they were recalling during the interview factors that had promoted readjustment during the first year after injury when they were in early or middle adolescence. The main consideration is whether the interviewees could recall how they were acting and thinking at the time of the injury or were they responding as mature adults. However, recollections, as such, are of significance regardless of their ‘objective’ validity. Other problems were that the interviews were not aimed to primarily search for coping strategies when they were conducted and that the group was heterogeneous regarding level of injury, age at injury and the time since injury. These factors may have influenced the use of coping strategies. We also had to consider how to interpret the definitions of the categories of BriefCOPE, because they are only defined by two examples in the instrument. The studied group was too small to compare any gender differences with how the persons used different strategies of coping. Girls have been previously reported to be more inclined to turn to others, think hopefully and resort to tension-releasing strategies.6 Neither was it possible to see any associations between outcome and the number of strategies used by the individuals. This study showed that the number of categories used per individual varied with a range of 5–15 categories. This variation could be explained by any of the following: (1) the stressful situation is complex and requires many different strategies, (2) many strategies are tried with respect to one aspect, and nothing works, (3) the situation changes over time, requiring different coping strategies. These explanations are not mutually exclusive (Susan Folkman, personal communication, 15 June 2011). According to Frydenberg and Lewis34, the number of strategies is less important than the effectiveness of the strategies in reducing stress for any individual. Further research may focus on the development of measures of coping that are more relevant to the experiences of adolescents with SCI so that interventions can be targeted to meet their specific needs. Therefore, prospective, longitudinal studies of coping with newly injured adolescents would be most helpful. To date, we also know little about how adolescents with SCI may differ in their use of coping compared with adults injured in adulthood. In addition, cultural differences in the strategies of coping could be further explored by cross-cultural studies. Educational programs should be designed to increase health-care providers’ knowledge about coping. This education should include emphasis on the fact that people from different cultures may tend to use different coping strategies. For example, in this study we found that ‘active coping’ was frequently used and there was little use of ‘religion’ as a coping strategy.

Conclusions

Adolescents who sustain SCIs use a variety of strategies to help them cope with the consequences of the injury. Many of these coping strategies are similar to those used by others facing stresses, but it is instructive to hear, in their own words, how young adults recall the coping strategies they used in the first year after their injury when they were adolescents and also how they view the process of coping. This information can be useful in helping future patients.

References

Chevalier Z, Kennedy P, Sherlock O . Spinal cord injury, coping and psychological adjustment: a literature review. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 778–782.

Lazarus R, Folkman S . Stress Appraisal and Coping. Springer Publishing: New York, NY, 1984, p 445.

Lazarus R, Launier R (eds). Stress-Related Transactions Between Person And Environment. Plenum: New York, 1978, p 327.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S . Coping and adaptation. In: WD G (ed.). The Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. Guilford: New York, 1984, p 282–325.

Kennedy P, Evans MJ, Berry C, Mullin J . A longitudinal analysis of psychological impact and coping strategies following spinal cord injury. Br J Health Psychol 2000; 5: 157–172.

Frydenberg E . Coping competencies: what to teach and when. Theor Pract 2004; 43: 14–22.

Pollard C, Kennedy P . A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: a 10 year review. Brit J Health Psychol 2007; 12: 347–362.

Frydenberg E (ed.). Adolescent Coping Advances in Theory Research and Practice, 2nd edn. Oxford, Routledge, 2008, p 337.

Seiffge-Krenke I . Coping With Chronic Illness in Adolescence: An Overview of Research From the Past 25 Years. Cambridge University Press: New York, 2001.

Anderson CJ, Vogel LC, Chlan KM, Betz RR . Coping with spinal cord injury: strategies used by adults who sustained their injuries as children or adolescents. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 290–296.

Chlan KM, Zebracki K, Vogel LC . Spirituality and life satisfaction in adults with pediatric-onset spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 371–375.

Carver CS . You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 1997; 4: 92–100.

Augutis M, Levi R, Asplund K, Berg-Kelly K . Psychosocial aspects of traumatic spinal cord injury with onset during adolescence: a qualitative study. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30 (Suppl 1): S55–S64.

Patton Q . Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd edn. Sage Publication: Newbury Park, California, 1990, p 530.

Mayring P . Qualitative Content Analysis 2000 [cited May 2011]. Available from: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-00/2-00mayring-e.htm.

Mayring P . Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse Grundlagen und Techniken, 7th edn. Deutscher Studien Verlag: (In German)Weinheim, 2000, p 117.

Augutis M, Levi R . Pediatric spinal cord injury in Sweden: incidence, etiology and outcome. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 328–336.

Augutis M, Malker H, Levi R . Pediatric spinal cord injury in Sweden; how to identify a cohort of rare events. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 337–346.

WHO (World Health Organization). 10 Facts on Adolescent Health 2008. [cited August 2011]. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/adolescent_health/en/index.html.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ . Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 50: 992–1003.

Frydenberg E . Understanding coping: social support as a major resource. In: Frydenberg E (editor). Learning to Cope: Developing as a Person in Complex Societies. Oxford University Press: Oxford UK, 1998, p 15–16.

Taylor SE, Stanton AL . Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2007; 3: 377–401.

Elfstrom ML, Ryden A, Kreuter M, Persson LO, Sullivan M . Linkages between coping and psychological outcome in the spinal cord lesioned: development of SCL-related measures. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 23–29.

Carpenter C . The experience of spinal cord injury: the individual's perspective--implications for rehabilitation practice. Phys Ther 1994; 74: 614–628 discussion 28–29.

Kerstin W, Gabriele B, Richard L . What promotes physical activity after spinal cord injury? An interview study from a patient perspective. Disabil Rehabil 2006; 28: 481–488.

Standal OF, Jespersen E . Peers as resources for learning: a situated learning approach to adapted physical activity in rehabilitation. Adapt Phys Act Q 2008; 25: 208–227.

Buunk AP, Zurriaga R, Gonzalez P . Social comparison, coping and depression in people with spinal cord injury. Psychol Health 2006; 21: 791–807.

Buunk AP, Zurriaga R, Gonzalez P, Terol C, Roig SL . Targets and dimensions of social comparison among people with spinal cord injury and other health problems. Brit J Health Psych 2006; 11 (Pt 4): 677–693.

Derlega VJ, Greene K, Henson JM, Winstead BA . Social comparison activity in coping with HIV. Int J STD AIDS 2008; 19: 164–167.

Hooper H, Ryan S, Hassell A . The role of social comparison in coping with rheumatoid arthritis: an interview study. Musculoskeletal Care 2004; 2: 195–206.

Chung MC, Preveza E, Papandreou K, Prevezas N . Spinal cord injury, posttraumatic stress, and locus of control among the elderly: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. Psychiatry 2006; 69: 69–80.

Kennedy P, Evans M, Sandhu N . Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: the contribution of coping, hope and cognitive appraisals. Psychol Health Med 2009; 14: 17–33.

Hagevi M . Religion och Politik (In Swedish). Malmö: Liber, 2005, p 239.

Frydenberg E, Lewis R . Adolescents least able to cope: how do they respond to their stresses? Br J Guid Couns 2004; 32: 25–37.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to associate professor Karl-Gustaf Norbergh, MidSweden University, for his help with the data validation. The study was supported by the Promobilia Foundation and the Norrbacka–Eugenia foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Augutis, M., Anderson, C. Coping strategies recalled by young adults who sustained a spinal cord injury during adolescence. Spinal Cord 50, 213–219 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.137

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.137