Abstract

The extent to which media employees can make highly individualized decisions has been debated extensively in existing studies on gatekeeping. This case study proposes a bottom-up approach by examining the news filtering practices of Chinese Party (Communist Party of China, CPC) media employees, aiming to expand and deepen research in this field. Drawing upon 16 interviews conducted within a Chinese Party media newsroom, this research explores the news filtering process among different job groups. The study reveals the stratification of filtering preferences within the newsrooms and identifies two forms of bottom-up resistance: resistance by grassroots journalists driven by cost-effectiveness, and resistance by journalists and senior editors rooted in social responsibility. Furthermore, the study confirms that a unified propaganda function is insufficient to compromise the bottom-up resistance of media employees; however, it remains within legitimate political boundaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the gatekeeping literature, despite the intricate and diverse factors influencing news content shaping, scholars persist in investigating individual decision-making behaviors (Vos, 2015). The degree to which media employees can exercise highly individualized decisions remains a subject of ongoing debate. Numerous studies have indicated that individuals within news organizations undergo a process of socialization, which influences their adherence to procedures and instructions established by editors, news directors, or other authoritative figures in the newsroom (Schudson, 2003; Ryfe, 2009; Hearns-Branaman, 2018; Wilner et al., 2021). However, contrasting perspectives exist. Arguments suggest that journalists may exhibit bottom-up resistance due to an increasingly deteriorating working environment (Ashraf Soherwordi and Javed, 2016; Sparks, 2017), tension between profit-driven motives and professional values (Bunce, 2019), or governmental and partisan constraints on press freedom (Lauk and Kreegipuu, 2010). These resistances will manifest in the conduct of individual news gatekeeping processes while exerting an impact on the production of news content.

This study focuses on Chinese party newspapers which have undergone market-oriented reform and have been influenced by journalistic professionalism since China’s reform and opening up policy. As a result of these changes, journalists working for Chinese party newspapers have gradually gained more autonomy and are no longer solely serving as propagandists for party policies. However, due to incomplete personnel system reforms within these newspapers, stratification exists among employees with younger employees often facing heavy workloads, unstable contracts, and unfair remuneration (Zhang, 2014; Zhao, 2014). Consequently, this situation has made it possible for grassroots journalists to resist top-down control (Sparks, 2017).

This paper examines the discourse of employees in Chinese party newspapers amidst social change and investigates the news filtering preferences of journalists, editors, and senior editors along the news production line. The findings of this study demonstrate that news filters among newsroom personnel encompass a dynamic process of negotiation, involving individual self-negotiation as well as negotiations between superiors and subordinates. These results affirm the presence of bottom-up resistance by employees in Chinese Party newspapers and underscore its efficacy in influencing media news shaping. Consequently, this study contributes to the discourse on mass media’s gatekeeping from an individual perspective while further enriching discussions on journalistic practice within non-Western nations.

Literature review

News filtering: a process of news selection

Since the seminal work of White (1950), which introduced the concept of Gatekeeping to the field of communication studies, a substantial body of research has been conducted to address the question: How does news undergo its shaping process? If we define gatekeeping as “the process of culling and crafting countless bits of information into the limited number of messages that reach people each day” (Shoemaker and Vos, 2009, p. 1), news filtering can be considered as a process of news stories selection based on specific criteria.

In journalistic practice, the process of news filtering usually contains a series of decision points (Shoemaker et al., 2001), journalistic gatekeepers “selectively gather, sort, write, edit, position, schedule, repeat, and otherwise massage information to become news” (Vos, 2019, p. 90). During the input phase, journalists engage in a pre-selection process to identify news stories they intend to pursue in their coverage. Meanwhile, during the output phase, editors select the stories deemed significant to feature in a newspaper or broadcast (Bruns, 2005). Despite the significant technological advancements in news media over the past few decades, this mode of linear process information transmission still holds an important position (Bro and Wallberg, 2018). News organizations continue to act as gatekeepers and make choices that ultimately have an impact on the public (Vos, 2019). Especially within traditional mass media outlets like newspapers and television newsrooms, the gatekeeper role continues to be upheld, regulating algorithmic news recommendations (Møller, 2022).

This study examines the linear process of information selection and transmission in the newsroom, referred to as news filtering. Throughout this intricate process, a multitude of filters come into play, exerting their influence and determining the value of news while partially explaining journalistic news selection.

Journalists as a bottom-up filter power

Pam Shoemaker and her colleagues (Shoemaker, 1991; Shoemaker et al., 2001; Shoemaker and Reese, 2013; Shoemaker and Vos, 2009) examine a range of factors and propose theoretical frameworks elucidating the impact of various pressures on shaping news content. They have systematically classified these influences into five distinct levels: individual level, media routines level, organizational level, social institutional level, and social system level. While scholarly consensus acknowledges that the news filtering process is not solely determined by individuals, there persists a sustained scholarly interest in comprehending individual decision-making behavior within this context (Vos, 2015). For example, the gatekeeping behavior of journalists and editors in the newsroom (Hellmueller, 2015; Phillips, 2015; Eliens et al., 2018; Rusdi and Rusdi, 2020).

The extent to which journalists exercise discretion, known as a form of individual-level gatekeeping, has been a highly contentious topic in these discussions. Many scholars argue that the subjectivity of journalists holds limited significance, as they contend that journalists’ influence on news production is overshadowed by top-down influences such as news routines, editorial department hierarchies and editors’ sway, the organizational culture within news companies, information sources, and other external factors beyond the control of journalists (Comeforo, 2010). Even if journalists exhibit a certain degree of agreement on specific issues, it does not mean that they all concur or “believe” the position is true; instead, as members of the news organization, they are required “to produce the same discourse” (Hearns-Branaman, 2018, p. 28), or may use common journalistic practices (Wilner et al., 2021). Herman (1985) defined this phenomenon as the socialization of journalists, which emphasizes that selection and promotion tend to be largely conformist. This includes journalists who either fully subscribe to the value system of a news organization from the outset or who gradually internalize the value system of the news organization or the elite group.

However, several studies propose that socialization does not engender enduring and absolute effects. The socialized individual engages in cognitive processes and behavioral responses that are contingent upon specific contextual circumstances, thereby enabling the potential for diverse modes of thinking and action when these circumstances undergo transformation (Sparks, 2017). In the realm of journalism, the objective divergence of interests among journalists, their managers, and employers is evident. Within a hierarchical division of labor, journalists, particularly those occupying lower positions, assume subordinate roles wherein their activities are directed by superiors. However, their remuneration and working conditions are not commensurate with the demands placed upon them, leading to significant levels of stress that may lead to resistance behaviors (Sparks, 2017). Meanwhile, the resistance from journalists may also stem from the inherent tension between news organizations’ profit-driven motives and the professional values of journalists (Bunce, 2019), as well as governmental and partisan constraints on press freedom (Lauk and Kreegipuu, 2010). These conflicts have the potential to enable lower-level journalists to confront top-down pressure, thereby establishing a bottom-up filtering mechanism for personal decision-making.

Present status of Chinese Party newspaper employees

China’s mass media systems exhibit characteristics of high-party parallelism (Zhao, 2011). This implies a strong nexus between the Chinese media and the CPC-led regime, wherein the party exercises absolute control over press operations (Wirz et al., 2021). The aforementioned feature was particularly conspicuous prior to China’s reform and opening up in 1978, when journalists functioned as Party propagandists tasked with reporting on Party meetings, activities of the Party and government leaders, as well as various accomplishments (Zhao, 1997). China initiated a market-oriented economy in the late 1970s, challenging the conventional top-down information dissemination. Numerous media outlets, including various local party platforms, have undergone a profound process of commercialization and no longer heavily rely on government subsidies (Zhao, 2000; Zhou, 2008). As a result, journalists in China’s party media have deviated from their original role as mere propagandists. On one hand, party journalists are striving for increased autonomy and placing greater emphasis on the quality and diversity of news content. On the other hand, Party media at all levels have also adjusted their propaganda strategies to allow for more journalistic independence within official boundaries in order to reach a wider audience.

The development of Chinese party media has been accompanied by reforms in the personnel management system. However, these reforms were not thorough enough. Specifically, a significant majority of employees who joined before the reform retained their status as government-affiliated institution staff (shiyebianzhi 事业编制), while those who joined after the reform were predominantly classified as enterprise staff (qiyebianzhi 企业编制). This resulted in a disparity between the two groups in terms of benefits, promotion opportunities, and job stability (Wu, 2015). Consequently, this internal stratification among journalists within Chinese Party media emerged. After conducting an in-depth analysis of the living conditions of Chinese journalists, Zhang (2014), a Chinese scholar, proposed that the class stratification among Chinese journalists can be aptly characterized as a hierarchical pyramid structure. At its pinnacle lies the elite class, comprising only a select few individuals, while at the base resides the grassroots journalists who primarily engage in journalism for their livelihoods. The escalating challenges faced by these professionals and the deterioration of their working conditions have significantly contributed to a profound social identity crisis among lower-level journalists, leading them to self-deprecatingly refer to themselves as “news migrant workers” (Zhao, 2014). Hassid (2011) referred to this cohort as “workaday journalists” who work mainly for money and lack a commitment to public service.

Research questions

Given the aforementioned discussion, in an increasingly demanding work environment, the manner and extent to which journalists exercise individual discretion in new filtering emerge as topics of scholarly discourse. In this study, news filtering pertains to the decision-making process undertaken by media professionals in curating news information and ultimately determining the content of news releases.

This study focuses on an underexplored area, namely the bottom-up news filtering mechanism of Chinese Party newspapers. Following media reform and significant transformations in the overall media market landscape, there has been a noticeable shift in the Party newspaper employees’ sense of identity in China, accompanied by a deterioration in their working conditions (Zheng, 2010; Lu and Zhang, 2016, Zhang, 2020, Hu and Wang, 2022). Given the current scenario, it is imperative to investigate emerging news filtering preferences within the newsrooms of Chinese party newspapers and potential journalists’ resistance. Therefore, this study aims to examine the news filtering practice of Party newspapers in China from a bottom-up perspective. Specifically, this study examines the news selection process employed by journalists and editors, as well as the underlying factors influencing their choices. Meanwhile, this study pays specific attention to the inherent conflict between upper and lower echelons. This research will be conducted based on the following questions:

RQ1: What are the news filtering preferences of employees at different hierarchical levels within the newsroom of Chinese Party Press?

RQ2: Do conflicting filtering preferences exist between superiors and subordinates? Is there any observed resistance?

RQ3: What are the sociocultural reasons behind such filtering and resistance behavior?

Methods and data

Case selection

The present study adopts a case study approach, focusing on Section E of A Daily (the Party newspaper of A City, China). Around 2010, various cities in China began to set up online government inquiry platforms (wenzhengpingtai 问政平台), and embedded party media as an important part. As a supervisor, the party media autonomously selects social governance issues reported by citizens on the platform and urges the government to address these problems through public opinion supervision (through news exposure). Among the numerous city party newspapers, A Daily stood out from many local party media with Section E and won the China News Awards. It can be said that Section E of A Daily serves as a reflection of the latest practice in public opinion supervision by Chinese party media. Meanwhile, considering that journalists and editors assigned to this section possess a relatively autonomous discretion in selecting their news topics, it presents an appropriate case for examination within this study. At the request of the interviewees, the media, and names of respondents were anonymized to protect their privacy.

Data collection

The study data is derived from interviews conducted with 16 respondents who are employed in Section E. Given the exploratory and open nature of the research question in this study, it was imperative to enhance the level of detail and richness through a continuous line of questioning. Hence, semi-structured interviews were employed as they allow interviewers to spontaneously generate follow-up inquiries based on participants’ responses and provide room for individual verbal expressions from participants (Hardon et al., 2004; Rubin and Rubin, 2011; Polit and Beck, 2010). The interview content encompassed two main aspects: (1) employees’ news filtering preferences and the rationale behind their choices, and (2) bottom-up resistance and its outcomes. The interview guide questions are presented in the Addendum for reference purposes.

A convenience sample of 16 media specialists, including grassroots journalists (entry-level employees), editors (mid-level employees), and senior editors (high-level employees) occupying various positions in the news production line, was selected to provide a more comprehensive analysis of negotiations between upper and lower echelons (see Table 1). To clarify, one of the aims of this study is to investigate how deteriorating working conditions affect journalists’ news filtering from a bottom-up perspective. Therefore, when selecting the sample of entry-level employees, we actively chose respondents who do not come from wealthy or politically influential backgrounds. At the same time, all respondent’s inclusion in the study was based on their positional relevance to the research focus as well as their willingness to participate in interviews. Reluctant or hesitant samples were excluded.

The data collection was conducted between June 28, 2022 and December 25, 2022.

Coding process

The database contains translated (from Chinese to English) 16 interview transcripts. The data was analyzed using the constant comparative method based on grounded theory (Boeije, 2002). Constant comparison involves the continuous coding of new data and comparing them with existing codes to generate concepts, thereby facilitating the development of a conceptual and saturated theory (Glaser, 2001). By engaging in constant comparisons, researchers can significantly enhance both the internal validity of findings and external validity (Boeije, 2002).

Three-step analysis was performed to answer the questions. First, comparison within a single interview. This involved a systematic process of open coding, wherein each passage from the interview was meticulously analyzed. Simultaneously, through comparing different segments of the interview, the coherence and consistency of the entire interview were examined. The primary objective of this internal comparison was to develop categories and accurately label them with suitable codes.

Secondly, comparison in this step was between interviews in the same group— journalist group (n = 8), editor group (n = 4), and senior editor group (n = 4). The codes obtained from individual interviews were compared, integrated, and categorized using axial coding. This step aims to enhance the conceptualization of the subject matter and identify existing code combinations, ultimately resulting in the formation of clusters or a typology.

Thirdly, coding results from three different groups are compared. The purpose of comparing interviews conducted with individuals who have a specific experience to those involving others who are involved but not directly undergoing the experience themselves is to enhance and augment the existing findings, thereby enriching the information obtained. This comparative analysis also serves as a means of validating an individual’s narrative, either by corroborating their account or raising doubts about its veracity.

Findings

The news filtering process within the Section E newsroom exemplified a dynamic negotiation between superiors and subordinates, operating within the boundaries of CPC’s propaganda control (see Fig. 1). Simultaneously, each position group presented distinct filtering principles that were contingent upon their work conditions and identity within China’s unique political, economic, and cultural context.

Journalists’ filters

The CPC exercises strict control over mass media in China. The basic principle of any journalist’s work as an employee of the CPC’s media was to adhere to the party’s command when choosing news clues or expressing a viewpoint. Respondents generally indicated that they would first exclude some topics and clues that were banned by CPC from discussion.

For news clues that were allowed, respondents would first make a preliminary screening based on “newsworthiness”, which was mainly an assessment of whether the event was a trending topic, whether the event was novel, whether the problem reflected by the event was serious, and so on.

We look for the most hotly discussed complaints on the platform first. If the complaint does indeed reflect a social problem that urgently needs to be addressed, that’s a good clue. (Bing, 35) The topic has to be new. If it is a commonplace issue, it would be meaningless. (Yun, 30)

High newsworthiness clues can improve the rate of publication, and culminate into a series of positive benefits such as bonuses, awards, and a sense of achievement for journalists.

Next, journalists decided which clues to choose from based on the principle of “cost-effectiveness”. Here, cost-effectiveness specifically refers to the comparison between the cost (time and money) invested in each news clue and the direct benefits (progress of completing the assessment targets) resulting from its publication. Respondents stated that each journalist had a strict monthly assessment as a journalist at the A Daily.

According to the current scoring standards, we have to publish 14 manuscripts a month. If a problem involves too many departments, the interview will take a lot of time and energy, so I would not choose to interview. If the incident occurs far away from the workplace and the transportation cost is too high, we will try to avoid it. (Yun, 30)

“Relationship maintenance” was another filter that significantly impacted journalists, and partly reflected their concerns about the instability of their carrier. Since Section E mainly reported on exposing scandalous issues, journalists were often under tremendous pressure to maintain good relations with the affected department and local government. Excessive exposure might result in government departments excluding and blocking journalists from future interviews, which might prove unfavorable to the development of a long-term career.

I dare not focus on one region or department for exposure. Because we expose bad things, they will hold grudges and think that I am targeting them. I really don’t want to offend them. There are many things at work that require their cooperation. It would be bad if we really get into trouble. (Tao, 31)

Therefore, when choosing news clues, journalists tended to avoid highlighting problems in the same region or involving the same department, repeatedly. As one interviewee (Jie, 32) said, “don’t hit the same person all the time, don’t get into trouble”.

It is important to note that respondents’ social responsibility filter was still functioning, although only three respondents mentioned this. Social responsibility means that individuals and companies must act in the best interests of their environment and society (Ganti, 2022). In the media field, social responsibility in supervision by public opinion meant the primary goal was to facilitate problem discovery and resolution, while personal gains and losses were secondary. As one interviewee (Qiang, 31) reported, “if a serious problem needs the media’s input to resolve, I will do it regardless of the cost. Because this is a party newspaper and the journalist’s responsibility. However, it is also tiring to keep doing so. I do not know how long it can last.”

Generally, under the CPC’s control, the process of news filtering by journalists (see Table 2) was a negotiation between personal interests and journalistic professionalism. Specifically, while journalists considered newsworthiness to be an important lead filter criterion, news clues that invested too much and produced too little would be discarded. Moreover, while some news clues were newsworthy, they may be abandoned in the interest of building a long-term harmonious relationship with the local government.

The cost-effectiveness can be regarded as a distinctive filtering mechanism, playing a pivotal role throughout the entire process. During the interview, respondents consistently emphasized that their identity as enterprise staff (qiyebianzhi 企业编制), which is distinct from that of long-standing employees (shiyebianzhi 事业编制), has significantly influenced their sense of security and professional identification. This factor serves as a crucial determinant for their focus on “cost-effectiveness”. As the interviewee mentioned, “My employment contract lacks stability… my primary focus lies in receiving a fixed salary rather than upholding journalistic ideals” (Jie, 32).

Editors’ filters

After journalists completed their interviews and wrote their articles, the editors filtered the news manuscripts further. As the main gatekeeper of the news articles of a party newspaper, they ‘adhere to the correct guidance of public opinion’ (jianchi zhengque yulundaoxiang 坚持 正确 舆论导向). This was the most important filter that editors adhered to. If they erred in this area, the consequences were serious, and their careers could be ruined. A respondent stated that many factors were considered when reviewing manuscripts.

For example, [we check] whether there are anti-party and anti-social elements in the manuscript, whether the direction and scale of criticism are in line with the requirements of the propaganda department, or whether the exposure of the problem is constructive and not just a simple accusation (Ge, 30).

Due to page limitations, editors were unable to publish every submitted article. Therefore, the “writing quality” of the article was the editor’s second filter. Editors checked the overall quality of news articles, such as newsworthiness, authenticity, and logicality, and rejected articles that failed to meet these requirements. However, respondents also reported that sometimes they had to compromise on writing quality. “Sometimes I struggle to find enough high-quality articles, but the newspaper cannot be left empty, so I can only compensate with some barely passable ones” (Zhou, 37).

The editor’s news filtering process (see Table 3) was relatively straightforward in comparison to the journalist’s filtering process. It can be viewed as a negotiation between writing quality and layout requirements, wherein editors aim to select manuscripts with writing quality while ensuring adequate page coverage.

The two-level filtering from journalists to editors was the filtering process for most news manuscripts in Section E. Senior editors intervened for some key topics and interviews.

Senior editors’ filters

The senior editor was responsible for reviewing key manuscripts and coordinating journalists’ participation in major interviews. In addition to their professional judgment, their filtering principles, to an extent, represented the requirements of the department director and even the CPC’s propaganda management department.

When planning a major interview, the CPC and the government’s focus was the most critical factor affecting decision-making. As one respondent said (Ling, 41), “Party newspapers are the mouthpiece of the CPC and the Government. We have to cooperate with the work of the Party and the government”. Therefore, senior editors usually combined Party and government’s work with their news coverage. For example, when A City was building a ‘civilized city’ (wenmingchengshi 文明城市), journalists were asked to expose issues surrounding urban hygiene and public order. When A City was building a ‘quality community’ (pingzhishequ 品质社区), journalists were asked to focus on finding problems in community management.

Social responsibility was also an important filter. The senior editors focused on exposing urgent urban management problems and arranged for journalists to interview, even if some news could potentially damage the local government’s reputation. As one respondent (Chen, 59) said, “we are also the watchers of social development. We need to discover problems in society promptly and give early warnings. This is the mission entrusted to us by the Party”.

However, based on pressures to survive, the senior editor would use appropriate measures to maintain relationships. In addition to cooperating with government departments, like journalists, they have to consider the interests of advertisers. Specifically, they may change their mind about reporting some news story. Of course, this may be based more on the will of the executive department manager. But this filter may not have been installed originally. As a respondent (Liu, 56) emphasizes, “this is not a decisive factor that hinders exposure. If the advertiser does have a serious problem, we would not advertise. This is also the principle that our director has been implementing”.

Generally, the filters of the senior editor (see Table 4) generally reflect the interests and perspectives of the party and government, guiding interview arrangements in accordance with their preferences. Different from the journalist group, the senior editor also uses the Relationship maintenance filter, but it contains more content - considering the maintenance of relationships with advertisers. Meanwhile, the social responsibility filter plays a more important role in the news filtering process of senior editors, creating a clear distinction between the journalist group and the editor group. Under this filter, the senior editor sometimes negates the government’s wishes as in many cases, the government does not want the problem exposed. Moreover, although business pressure will allow some compromises in decision-making, the mission of Section E in “solving urban governance problems” is still the bottom line.

Bottom-up resistance

The interviews and observations showed that employees’ bottom-up resistance was mainly reflected in two aspects. In the first instance, the senior editor and editor advocated for more complex and evenly distributed news clues, while journalists resisted based on the filter of cost-effectiveness.

According to one interviewee, journalists often force editors to use their manuscripts by collectively controlling the number of manuscripts submitted.

We roughly know how many manuscripts are needed for this section every month. Through private discussion, we decide not to provide too many manuscripts, and the editors have to adopt our manuscripts if there are no enough manuscripts. (Rong, 30)

In addition, they will manifest their dissent towards intricate clues or remote interviews by opting for less efficient working methodologies, such as selecting cost-effective yet slower public transportation to reach the interview venue.

Unless the company gives us an official ride, we’ll just take a bus to the interview site, even if it’s slower. If we drive ourselves, the money for gas might not be covered by the manuscript fee… We can’t be too efficient or they’ll expect us to do this kind of work every day. (Yun, 30)

Respondents reported that their approach yielded relatively favorable results. While Section E serves the entire City of A, recent years have seen a concentration of problem exposures in the core area around the newspaper offices, according to department statistics. As a result, Section E has received a number of complaints from local authorities in the core areas about this unfair treatment.

The second was pressure from the government and advertisers but journalists and editors resisted based on social responsibility. To counter the pressure, respondents said they commonly adopted a ‘two-step’ reporting strategy as a means of resistance.

We’ll start investigating on-site based on a tip we received from the public. If we confirm that the issue is real and requires media attention, we’ll publish a preliminary news report without giving prior notice to the companies and government departments involved. After our initial coverage is released, these entities will try to address the problem while expecting us to continue reporting on it in order to restore their reputation. (Liu, 56)

Additionally, in order to mitigate potential conflicts with advertisers and relevant government agencies, journalists and editors have utilized a constructive writing approach. Specifically, the primary focus of all news coverage lies in identifying and resolving issues rather than attributing blame or assigning responsibility. “By taking this approach, we not only address the issue but also positively report on the related company or government as they actively rectify their mistakes” (Qiang, 31).

Discussion

This study contributes to the existing literature on gatekeeping at the individual level by examining the news filtering mechanism of Chinese party media from a bottom-up microscopic perspective. Specifically, this study elucidates how journalists, editors, and senior editors engage in news filtration within a Chinese party press newsroom and establishes a model for understanding this process.

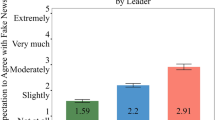

Firstly, the model reveals a discernible stratification of news filtering preferences within Section E newsrooms, wherein employees with diverse levels and identities adhere to different filtering principles. Journalists at lower hierarchical levels have emphasized the significance of employing Cost-effectiveness filters, exhibited a diminished sense of Social responsibility, and primarily perceived their occupation as a means of livelihood. At the opposite end of the spectrum, senior editors within the newsroom prioritize Social responsibility to a greater extent. They possess a robust professional identity and perceive it as their obligation to serve the journalistic mission of the CPC, aspiring to foster societal progress through their work. Editors at the intermediate level resemble workers on an assembly line, as their primary task is to maximize manuscript quality while adhering to newspaper layout requirements. In addition to contributing to the existing literature on gatekeeping, the findings of this study also partially validate the stratification of Chinese media employees from the perspective of news filtering (Hassid, 2011; Zhang, 2014).

Meanwhile, findings also unveil two forms of bottom-up resistance observed in the newsroom. The first form entails editors and senior editors demanding higher Writing quality, while journalists resist based on considerations of Cost-effectiveness. The resistance arises from a deteriorating working environment experienced by grassroots journalists, characterized by mounting job challenges, diminishing economic benefits, and inequitable contracts compared to older generations of employees. This phenomenon aligns with the argument that the presence of unstable and deteriorating working conditions can indeed cause resistance behavior among grassroots journalists (Ashraf Soherwordi and Javed, 2016; Sparks, 2017). In addition, this perception also challenges the arguments about journalists’ manner of socialization (Schudson, 2003, Ryfe, 2009). The socialization of journalists is not only evident in their gradual assimilation with upper-level management for long-term benefits, such as job promotion, but it can also manifest as resistance to higher job demands based on personal short-term gains, like completing monthly assessments at a low cost.

Another conflict identified in this study pertains to the pressure exerted by local governments and advertisers, which is met with resistance from media employees who prioritize social responsibility filters. This conflict demonstrates the inherent duality of Chinese media. After the 1980s, Chinese media, including Party-affiliated outlets, underwent structural reforms and adopted a dual-attribute approach to journalism. On one hand, they entered the market and embraced “enterprise management” to engage in competition; on the other hand, they shouldered the responsibility of being “the mouthpiece of the party, government, and people” (Wang, 2011). Consequently, this dynamic perpetuates a game between traditional power mechanisms and market forces. Based on the findings of the study, the successful resistance by employees of Chinese party media further highlights the leading role of the propaganda mode within China’s two coexisting news modes (Lu and Zhang, 2014).

Additionally, the findings of this study validate that both forms of bottom-up resistance play a role in influencing the news filtering process through astute strategies. These empirical findings from China contribute to the ongoing discourse on whether journalists possess autonomy in making individualized decisions during the gatekeeping process. Moreover, the second form of resistance, namely media employees’ resistance grounded in social responsibility, lends support to Sparks’ (2017) argument that, because of the bottom-up resistance of working-class journalists, mass media does not only have a unified propaganda function but can systematically express dissent within a legitimate political sphere. In China’s media landscape, the media possesses the autonomy to constructively expose governmental and corporate issues. However, this kind of expression in China is subject to limitations, and negotiations from the bottom-up occur only within the boundaries set by the CPC. As all respondents put “Party’s control” at the top of the filtering principle.

Conclusion

Although this study provides insights into the news filtering mechanism of Chinese media from a bottom-up perspective, the research is limited to one city-level party media and a singular genre of news reporting. Within the constructivist framework and technology use (Schrader, 2015), there are numerous opportunities for diverse media communities to further enrich the bottom-up news filtering mechanism of Chinese media. Therefore, more research is needed. At the same time, although this study has explored the effect of journalists’ resistance, it still needs to be in-depth, and a more scientific test method is worth further exploration.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitivity of the identity of Party newspaper workers in China. Respondents have expressed their preference for keeping the original interview data confidential to ensure privacy protection. However, datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ashraf SI, Soherwordi SHS, Javed T (2016) Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model: its application on electronic media and journalists in Pakistan. J Polit Stud 23(1):273

Boeije H (2002) A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant 36(4):391–409

Bro P, Wallberg F (2018) Gatekeeping in a digital era: principles, practices and technological platforms. In: Theories of Journalism in a Digital Age. Routledge. pp. 219–232

Bruns A (2005) Gatewatching: collaborative online news production. vol. 26. Peter Lang

Bunce M (2019) Management and resistance in the digital newsroom. Journal 20(7):890–905

Comeforo K (2010) Review essay: manufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass media. Glob Media Commun 6(2):218–230

Eliëns R, Eling K, Gelper S, Langerak F (2018) Rational versus intuitive gatekeeping: escalation of commitment in the front end of NPD. J Prod Innov Manag 35(6):890–907

Ganti A (2022, June 23) Social responsibility definition. Investopedia. Retrieved June 29, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/socialresponsibility.asp

Glaser B (2001) The GT perspective: conceptualization contrasting with description. Mill Valley

Hardon A, Hodgkin C, Fresle D (2004) How to investigate the use of medicines by consumers. In How to investigate the use of medicines by consumers. World Health Organization. pp. 89–89

Hassid J (2011) Four models of the fourth estate: a typology of contemporary Chinese journalists. China Q 208:813–832

Hearns-Branaman JO (2018) What the propaganda model can learn from the sociology of journalism. In: Pedro-Carañana J, Broudy D, Klaehn J (eds.) The propaganda model today: filtering perception and awareness. University of Westminster Press, London, pp 25–36

Hellmueller L (2015) Journalists’ truth justification in a transnational news environment. Gatekeeping in transition. Routledge, New York, pp. 47–64

Herman ES (1985) The real terror network: terrorism in fact and propaganda. Black Rose Books

Hu L, Wang XH (2022) 胡蕾&王兴华 (2022) 媒体转型发展中新闻记者对职业认同与困惑的调查分析 (Investigation and analysis of journalists’ professional identity and confusion in media transformation and development). 传媒 (Media) 18:81–83

Lauk E, Kreegipuu T (2010) Was it all pure propaganda? Journalistic practices of ‘silent resistance’ in Soviet Estonian journalism Acta Historica Tallinnensia 15:167–190

Lu J, Zhang T (2014) Linguistic intergroup bias in Chinese crime stories: propaganda model vs. commercial model. Asian J Commun 24(4):333–350

Lu X, Zhang FD (2016) 刘昶&张富鼎 (2016). 中国广播电视记者现状研究—基于社会学的某种观照 (A study on the current situation of Chinese radio and television journalists—based on some sociological observations). 现代传播 (Mod Commun) 03:21–31

Møller LA (2022) Recommended for you: how newspapers normalise algorithmic news recommendation to fit their gatekeeping role. Journal Stud. 23(7):800–817

Phillips A (2015) Futures of journalists: Low-paid piecework or global brands?. In Gatekeeping in transition. Routledge. pp. 65–82

Polit DF, Beck CT (2010) Essentials of nursing research: appraising evidence for nursing practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Rubin HJ, Rubin IS (2011) Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Sage

Rusdi F, Rusdi Z (2020, May) The role of online media gatekeeper in the era of digital media. In: Tarumanagara International Conference on the Applications of Social Sciences and Humanities (TICASH 2019). Atlantis Press. pp. 542–544

Ryfe DM (2009) Broader and deeper: a study of newsroom culture in a time of change. Journalism 10(2):197–216

Schrader DE (2015) Constructivism and learning in the age of social media: Changing minds and learning communities. N Direct Teach Learn 2015(144):23–35

Schudson M (2003) The sociology of news. Norton, New York, NY

Shoemaker PJ, Eichholz M, Kim E, Wrigley B (2001) Individual and routine forces in gatekeeping. Journal Mass Commun Q 78(2):233–246

Shoemaker P J (1991) Gatekeeping. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications

Shoemaker PJ, Reese SD (2013) Mediating the message in the 21st century: a media sociology perspective. Routledge

Shoemaker PJ, Vos T (2009) Gatekeeping theory. Routledge

Sparks C (2017) Extending and refining the propaganda model. Westminst Pap Commun Cult 4(2):68

Vos TP (2015). Revisiting gatekeeping theory during a time of transition. In Gatekeeping in transition. Routledge. pp. 3–24

Vos TP (2019) Journalists as gatekeepers. In: The handbook of journalism studies. Routledge. pp. 90–104

Wang X (2011) (王肖潇) (2011). 从身份认同看建国后记者的职业身份转变 (The transformation of journalists’ professional identity after the founding of the People’s Republic is viewed from the perspective of identity). 新闻传播 (Journal Commun) 6:127–128

White DM (1950) The “gate keeper”: a case study in the selection of news. Journal Q 27(4):383–390

Wilner T, Montiel Valle DA, Masullo GM (2021) “To me, there’s always a bias”: understanding the public’s folk theories about journalism. Journal Stud 26 22(14):1930–46

Wirz CD, Shao A, Bao L, Howell EL, Monroe H, Chen K (2021) Media Systems and attention cycles: Volume and topics of news coverage on COVID-19 in the United States and China. Journal Mass Commun Q 107769902110494. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776990211049455

Wu G (2015) (吴光振) (2015) 传统媒体迎来人事制度改革时机 (Traditional media ushered in the opportunity of personnel system reform). 青年记者(Young-. Journalists) 33:23–24

Zhang L (2020) (张兰) (2020). 新媒体环境下新闻从业者职业认同危机 (The crisis of professional identity of journalists in the new media environment). 青年记者 (Youth Journalist) 36:79–80

Zhang Q (2014) (张泉泉) (2014). 重塑知识生产者形象—公民新闻时代专业记者的再定位 (Reconstructing the image of knowledge produce—repositioning professional journalists in the era of citizen journalism). 江淮论坛 (JiangHuai forum) 1:147–152

Zhao Y (1997) Toward a propaganda/commercial model of journalism in China? The case of the Beijing Youth News. Gaz (Leiden-, Neth) 58(3):143–157

Zhao Y (2000) From commercialization to conglomeration: the transformation of the Chinese press within the orbit of the party state. J Commun 50(2):3–26

Zhao Y (2014) (赵云泽) (2014). 记者职业地位的陨落: “自我认同”的贬斥与“社会认同”的错位 (The decline of journalists’ professional status: the dissonance of “self-identification” and “social identification”). 国际新闻界 (Chin J Journal Commun) 12:84–97

Zhao Y (2011) Understanding China’s media system in a world historical context. In: Comparing media systems beyond the western world. Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–174

Zheng LY (2010) 郑丽媛 (2010). “新闻民工”:媒体的悲哀? (‘News migrant workers’ : the media’s woes?). 新闻战线 (Press) 06:57–58

Zhou S (2008) China: media system. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. pp. 1–7

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to all individuals who actively participated in the survey. Special appreciation is also extended to Jonathan Sullivan (ID 0000-0001-7275-6737) from the University of Nottingham, UK, for his invaluable insights and comments during the revision process of this article. The present study is funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (23NDJC253YB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhongzhong Fu performed the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision, and funding acquisition; Han Yan performed the methodology, investigation, data curation, and formal analysis; Zhongnan Fu performed the investigation, data curation, and formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the ESRC (2012) Framework for Research Ethics. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Nottingham Ningbo China (Date 2022/06/27).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants who gave an interview and were included in the study. As the authors of this paper, we undertook not to include any personal identifying details of the participant, as well as photographs or social media profiles.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Z., Yan, H. & Fu, Z. Negotiation within legitimate political boundaries: revealing the bottom-up news filtering of Chinese Party newspapers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 607 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03141-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03141-y