Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) gained global notoriety as a preventable public health menace affecting 30% of women worldwide. The IPV which is implicated as a significant cause of premature mortality and morbidity worldwide, increased during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The purpose of this study is to synthesize evidence regarding the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the incidence of IPV in Africa, occurring between 1st January, 2020 to 31st December, 2022. Using the Tricco et al. (2018) procedure, a thorough literature search was done in PubMed, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Dimensions, Taylor and Francis, Chicago Journals, Emerald Insight, JSTOR, Google Scholar, and MedRxiv. Consistent with the inclusion and exclusion protocols, 10 peer-reviewed articles were eligible and used for this review. We report that : (i) the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic escalated the vulnerabilities of people to economic hardship, resulting in the increased incidence of IPV between 2020 and 2022 in Africa, (ii) psychological/emotional abuse was the most prevalent form of IPV suffered by victims, (iii) mental health conditions were the most reported effects of IPV on victims. The prevalence of IPV could undermine the achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDG)s 2.2, 4, 5.2, 11.7, and 16 by Africa, limiting the continent’s quest to achieve full eradication of all types of violence against women. This study appears to be the first to review the literature on how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic influenced the incidence of IPV in Africa. We recommend that governments provide women with financial support using social support schemes, create sustainable livelihood opportunities for women, and intensify public sensitisation and education about IPV and available help-seeking opportunities. We recommend a study into the structures available for dealing with IPV in Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has attained global notoriety as a preventable public health menace affecting 30% of women in intimate relationships worldwide (United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], 2021a; 2021b; 2021c; World Health Organisation [WHO], 2017). Global estimates of IPV prevalence showed that 23% and 38% of cases were from high-income countries and the developing world, respectively (Anderson, 2021; UNFPA, 2021a; 2021c; WHO, 2017). Furthermore, about 13% of women suffer physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime (WHO, 2019; 2018). IPV is also implicated as a significant cause of premature mortality and morbidity worldwide (Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022; WHO, 2013).

As a global phenomenon, IPV defies culture, level of development, and religion (Ellsberg et al., 2014; UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b). The phenomenon could be defined as violence potentially occurring between two or more individuals in a present or former intimate relationship (Macassa et al., 2022). WHO (2010) defines it as a behaviour within an existing or previous intimate relationship that results in physical, sexual, or psychological harm, including acts like physical violence, sexual compulsion, psychological exploitation, and domineering conduct. The term IPV was deliberately crafted to differentiate it from other forms of domestic violence such as elderly and child violations (Macassa et al., 2022). Typically, males are found to be the main perpetrators in most IPV cases (Teshome et al., 2021). However, there are studies (Adejimi et al., 2014; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015) that reported females as perpetrators too (Macassa et al., 2022). Though IPV predated the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, the pandemic became a significant addition to the predictors of this social menace for various reasons (Duncan et al., 2020; Gottert et al., 2021; Jarnecke and Flanagan, 2020; John et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020; United Nations Women [UNW], 2020a).

The fear of the pandemic ignited a global panic, forcing many leaders across the globe to adopt control measures that were mostly reactionary (Campbell, 2020; WHO, 2020a; 2020b; Tadesse et al., 2022). These measures included restrictions on human activities, movements, and community lockdowns, in most cases (Gottert et al., 2021; Undie et al., 2021). Evidence on the impact of the pandemic reported disturbing increases in the incidence of IPV, especially against women globally (Sharma and Borah, 2020; Undie et al., 2021). For instance, the stay-at-home orders by leaders resulted in most partners spending far more time together at home (than usual) and thus, increased the exposure to the IPV. Unfortunately, many people also lost their jobs and became economically disadvantaged, igniting incidents of stress, anxiety, depression, frustration, and hopelessness (Mazza et al., 2020; Roesch et al., 2020). Moreover, there were no avenues for victims to report perpetrators and explore other help-seeking opportunities (Gottert et al., 2021; UNW, 2020a; 2020b). Thus, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic exacerbated the pre-existing predictors of IPV and its impact was worldwide (Moreira and Da Costa, 2020; Tadesse et al., 2022).

IPV impacted individuals, families, communities, and society at large, and threatened global efforts at achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) 2.2, 4, 5.2, 11.7, and 16 (Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022; UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c; WHO, 2016a; 2016b). The SDG 2.2, provides, inter alia, for an end to malnutrition of all kinds, especially among young women and also pregnant or breastfeeding women everywhere. The SDG 4 guarantees equity and inclusivity in education as a means to promoting sustainable learning avenues for all, while SDG 5 guarantees gender parity and employment for all women. Again, SDG 11.7 guarantees unlimited access to safe and inclusive green and public spaces, especially for females. Also, SDG 16 provides, inter alia, for societies of peace, justice, inclusiveness, and accountability to ensure sustainable development for all (Shewangzaw et al., 2022; UNFPA 2021a; 2021b; 2021c; WHO, 2016a; 2016b).

Meanwhile, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had a significant impact on IPV rates globally, including in Africa (Meinck et al., 2017; UNFPA, 2021b; 2021c). In Africa, IPV was already an issue of public health concern even before the pandemic (Meinck et al., 2017; UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). Evidence showed that the majority (33%) of the cases of IPV globally occurred in Africa (Tadesse et al., 2022). Moreover, the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on Africa has been disproportionate (Tadesse et al., 2022). Several factors such as gender inequalities, and social norms that trigger and perpetuate violence, poverty, and armed conflict are implicated in this reality (Duncan et al., 2020; Jarnecke and Flanagan, 2020; John et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2016a; 2016b; UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). The pandemic has exacerbated these issues, resulting in an escalation of IPV across the continent, with Kenya and a few other countries recording spikes in unintended pregnancies (UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). For instance, Shitu et al. (2021) revealed that the majority of the female victims of IPV were economically disadvantaged. Moreover, females with low levels of formal education, and females with domineering, unemployed, and alcoholic partners suffered more IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 (Moreira and Da Costa, 2020; Roesch et al., 2020).

Additionally, data on Africa revealed that countries such as South Africa, Tunisia, Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Zimbabwe reported an increased incidence of IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 than the pre-pandemic period (Plan International, 2020). Importantly, specific information about the scope of IPV in Africa during the pandemic differs from country to country and region to region (UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). Different countries have data collection systems and reporting capabilities that vary in scope and accuracy (Sikweyiya et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2016a; 2016b). Furthermore, many cases of IPV must have gone unreported due to fear, stigma, and other barriers that prevent victims from coming forward (Shitu et al., 2021; UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c; WHO, 2017).

Consistent with SDGs 2.2, 4, 5.2, 11.7, and 16, it is immoral that one in three females die every three days due to IPV associated with SARS-CoV-2 lockdown measures (Tochie et al., 2020). Organisations such as UNFPA and governments across the African continent sought to address the canker of IPV. This includes inert alia, implementing awareness campaigns, victims support services, and measures to hold perpetrators to account (UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). However, it is important to recognise that more efforts are needed to effectively combat IPV and protect vulnerable populations. Thus, it is incumbent on researchers to expose the ills of IPV and give voice to the victims. Given this background, there is a need to scale up research and garner more evidence on the phenomenon in Africa. Though, studies exist on IPV in Africa, overall, there is not enough literature on the “true” state of the phenomenon (Shitu et al., 2021). Moreover, there is a need for evidence mapping to guide policy and practice that aims to prevent the phenomenon and its associated health, family, and social implications. Thus, there is limited evidence on how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic influenced the incidence of IPV in Africa (Adejimi et al., 2014; Anderson, 2021; McCloskey et al., 2016; Meinck et al., 2017; Sikweyiya et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2016a; 2016b). Therefore, the purpose of this review is to synthesize evidence to establish the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the incidence of IPV in Africa, between 1st January, 2020 to 31st December, 2022.

Methods

We used peer-reviewed articles (PRAs) only to explore the incidence of IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak from the African perspective. Guided by Tricco et al. (2018) checklist, we examined, synthesized, and analysed relevant PRAs. The technique involved: (i) defined and examined the purpose/objective of the review, (ii) reviewed questions developed and thoroughly examined them, (iii) identified and examined article search terms, (iv) identified and explored relevant databases and downloaded articles, (v) mined data; (vi) summarised data and synthesized results, and (vii) conducted consultation (Tricco et al., 2018). Consequently, five research questions guided the review: (i) what is the prevalence of IPV in Africa between 2020–2022? (ii) what factors account for IPV in Africa between 2020–2022? (iii) What is the gender dynamic of IPV in Africa between 2020 and 2022? (iv) what are the impacts of IPV on victims in Africa between 2020–2022? (v) what coping strategies were employed by victims of IPV in Africa between 2020–2022?

Materials and methods

Search strategy

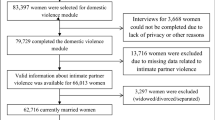

We relied on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) to conduct this review (Tricco et al., 2018; Munn et al., 2018). The following databases were sources of the PRAs used in this review: PubMed, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, Dimensions, Taylor and Francis, Chicago Journals, Emerald Insight, JSTOR, Google Scholar, and MedRxiv (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). To attain rigour and comprehension in the search strategy, we consulted the PubMed database for MeSH terms on the subject. The first level search covered “Partner Violence” OR “Spousal Abuse” OR “Domestic Violence” OR “Covid-19” OR “Economic Hardship” yielding 431 articles. Relying again on the MeSH terms, a more comprehensive and detailed second-level search was conducted across an additional 10 virtual databases which also yielded a total of 2686 articles and reports (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). The search covered studies conducted around 1st January, 2020, to 31st December, 2022. Meanwhile, the study itself was done between September, 2022, to 28th February, 2023. All duplicate citations were eliminated after the initial search. Downloaded articles were initially screened by all authors using titles and abstracts. Thus, articles deemed consistent with the inclusion criteria (described below) went through a thorough and complete review. Where the legibility of an article is in doubt, they were referred to authors Edward W. ANSAH, Nkosi N. BOTHA, and Anthoniette ASAMOAH for discussion until a consensus was attained. To ensure that the search was thorough and exhaustive, citation chaining was conducted on all papers that met the inclusion criteria to identify potentially relevant papers for further assessment. Moreover, a Clinical Psychologist, a Social Welfare Officer, a Police Officer from the Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit (DOVSU), and a Senior Officer from the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection were contacted for their recommendations.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies conducted in Africa that examined IPV in relation to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outbreak, using quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods qualified for admission. In addition, studies conducted around 1st January, 2020 to 31st December, 2022, were also admitted. Also, the papers must provide details on author(s), purpose/aim, methods/setting, forms of violation/factors, gender dynamics, impact on victims, coping strategies, and conclusion/recommendation. However, studies conducted before 1st January, 2020 were dropped. In addition, studies conducted outside of Africa, and devoid of details on author(s), purpose/aim, methods/setting, forms of violation/factors, gender dynamics, impact on victims, coping strategies, and conclusion/recommendation were dropped. Commentaries, grey literature, opinion pieces, and media reports were also excluded from this review.

Quality rating

Consistent with Tricco et al. (2018) protocols, each paper that met the inclusion criteria was assigned a quality rating. The checklist describes a systematic scale for papers to be included in systematic/scoping reviews. To qualify for admission, each paper must contain a research background, aims and objectives, context, appropriateness of design, sampling, data collection and analysis, reflectivity, value of research, and ethics. The papers were assessed and total scores were assigned based on the majority of sections. Studies scoring “A” had few or no limitations, “B” had some limitations, “C” had substantial limitations but carried some value, and “D” contained significant flaws that could undermine the study as a whole. Therefore, papers scoring “D” were excluded from the review (Tricco et al., 2018).

Data extraction and thematic analysis

Authors 2, 3, 4, and 5 independently extracted the data. Authors 2 and 4 extracted data on authors, purpose or aim, methods or setting, forms of violations, factors of violations, and forms of violations. Also, authors 3 and 5 extracted data on the predictors of IPV, gender dynamics, impact of IPV on victims, coping strategies, and conclusions (see Table 2). Using Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic analysis was conducted by authors 1 and 5. Thus, data were coded and themes emerged directly from the presented data, devoid of pre-conceived themes and yet consistent with the research questions (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The stages of analysis included the repeated reading of the text to familiarise with data, developing initial codes, exploring the themes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming themes, and generating the report. In addition, the themes that emerged were exhaustively discussed by all authors until consensus was attained. The themes were continuously reviewed based on new data until the final themes emerged.

Results

We conducted a retrospective investigation, from 2020 to 2022 into the incidence of IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Africa. Out of the 10 articles that were used for this review, eight employed quantitative design and two qualitative. Specifically, included articles covered 2020—2(20%) and 2021 and 2022—4(40%) each. Moreover, we found that the continental distribution of articles on IPV seems to be concentrated around Ethiopia. Thus, Ethiopia 5 (50%) (Gebrewahd et al., 2020; Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022; Shitu et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2022; Teshome et al., 2021), Nigeria 2(20%) (Fawole et al., 2021; Ojeahere et al., 2022), Kenya 1(10%) (Gottert et al., 2021), Tunisia 1(10) (Sediri et al., 2020), and Zimbabwe 1(10%) (Turner et al., 2022).

Forms of violations

We report that three main types of IPV occurred during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Africa including physical violence, psychological violence, and sexual violence. From the 10 articles reviewed, 9(90%) (Fawole et al., 2021; Gebrewahd et al., 2020; Gottert et al., 2021; Ojeahere et al., 2022; Sediri et al., 2020; Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022; Shitu et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2022; Teshome et al., 2021), reported all three main forms of violations including emotional, physical, and sexual violations. However, Turner et al. (2022) reported only sexual abuse. Meanwhile, each of these reported abuses has clear implications for the realisation of the SGDs 3, 4.7, 5, 9, 16.1, 16.2, and 16.a, all of which are aimed at mainstreaming human rights for all.

Predictors of IPV

We report that the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak-induced economic hardship in Africa may have significantly influenced the incidence of IPV. Review of the 10 PRAs revealed a number of predictors of IPV including the SARS-CoV-2, economic hardship, substance abuse by partners, age of the victim, perceived body image of the victim, level of formal education of partner, depression, spending more time together, domestic duties, social status, and normalisation of IPV by community members. Thus, 5(50%) (Fawole et al., 2021; Gebrewahd et al., 2020; Sediri et al., 2020; Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022; Turner et al., 2022) reported SARS-CoV-2, 6(60%) (Fawole et al., 2021; Gebrewahd et al., 2020; Gottert et al., 2021; Sediri et al., 2020; Teshome et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2022) economic hardship, and 3(30%) (Gottert et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2022; Teshome et al., 2021) substance abuse by partners. Others include 2(20%) (Shitu et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2022) level of formal education of partner, 1(10%) (Shitu et al., 2021) age of the victim, 1(10%) (Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022) perception of body image of victim, 1(10%) (Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022) depression, 1(10%) (Gottert et al., 2021) spending more time together, 1(10%) (Gottert et al., 2021) domestic duties, 1(10%) (Shitu et al., 2021) social status, and 1(10%) (Tadesse et al., 2022) normalisation of IPV by community contributed to increasing IPV incidence in Africa during the pandemic.

Gender

We further report that far more females suffered IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Africa than did the males. The PRAs showed that 7(70%) (Fawole et al., 2021; Gebrewahd et al., 2020; Sediri et al., 2020; Shewangzaw Engda et al., 2022; Shitu et al., 2021; Tadesse et al., 2022; Teshome et al., 2021) reported violence against females. Moreover, the problem was reported in 3(30%) studies (Gottert et al., 2021; Ojeahere et al., 2022; Turner et al., 2022) involving both males and females. Meanwhile, the SDGs, particularly 4 and 5, provide for the promotion and protection of gender rights and the elimination of all forms of gender-based violence.

Impact of IPV on victims

We also report that victims of IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 period in Africa suffered more symptoms of mental health than any other form of IPV-related impact. It is evident from the PRAs that 5(50%) (Fawole et al., 2021; Gebrewahd et al., 2020; Ojeahere et al., 2022; Sediri et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2022) reported symptoms of mental health as the impact of IPV on victims, 2(20%) (Ojeahere et al., 2022; Sediri et al., 2020) social media addiction, 1(10%) (Fawole et al., 2021) accepting abuse as normal, and 1(10%) (Turner et al., 2022) unwanted pregnancy.

Coping strategies

Furthermore, we report that victims of IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 period in Africa adopted very few strategies for containing the abuse. We found that 1(10%) (Sediri et al., 2020) of articles reported overreliance on social media as a coping strategy by victims of IPV, 1(10%) (Fawole et al., 2021) reported running away from IPV perpetrators, 1(10%) (Shitu et al., 2021) considered IPV as part of the culture (normalisation), and 1(10%) (Turner et al., 2022) refused to report perpetrators for the sake of peace.

Discussion

Intimate partner violence predated the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, but the surge in its incidence during the pandemic became a cause of public health concern. In two pre-pandemic studies, Izugbara et al. (2020) and Ssentongo et al. (2020), the Democratic Republic of Congo was found to record the highest IPV prevalence in Africa. However, in another pre-pandemic study by Wado et al. (2021), Gabon emerged as the country with the highest IPV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa. Contrary to these pre-pandemic studies, the current study identified Ethiopia as the country with the highest IPV prevalence during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Africa, accounting for 50% of PRAs on IPV incidence. Meanwhile, consistent with most pre-pandemic studies (Izugbara et al., 2020; Ssentongo et al., 2020; Wado et al., 2021), we are of the view that some IPV cases that occurred during the pandemic were neither reported nor studied. Furthermore, the findings of the current study could mean that Ethiopia had a more effective IPV reporting system that enabled victims to report. However, this should be understood within the context of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, where countries adopted mixed strategies in containing the pandemic including lockdowns. Thus, partners who hitherto never spent time together for longer periods, now had to do so. Overall, the pandemic-induced IPV could cost Africa its quest to attain the SGDs related to health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4), gender equity (SDG 5), disability rights (SDG 4a, 10.2, 17.18), and employment (SDG 8).

Forms of violations

Psychological/emotional abuse was the most prevalent form of IPV suffered during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, accounting for over 60% of all forms of IPV reported. Moreover, apart from the three commonest forms of IPV (emotional, physical, and sexual violations), economic/financial abuse also emerged during the pandemic. This finding upholds previous studies (Dwarumpudi et al., 2022; Izugbara et al., 2020; Peterman et al., 2022; Tiruye et al., 2020) that reported emotional abuse as the most prevalent form of abuse employed by perpetrators of IPV. However, the current study contradicts pre-pandemic studies (Ssentongo et al., 2020; Wado et al., 2021), that found sexual and physical abuse as the only forms of IPV employed by perpetrators. Overall, considering studies on IPV in Africa before and during the pandemic, emotional violence appears to be the most prevalent form of IPV. Therefore, there appears to be a correlation between emotional violence and the other forms of IPV.

Thus, it is safe to say that emotional violence could be both a cause and consequence of other forms of IPV, which was evident during the global pandemic. Therefore, the findings bring the issue of mental health to the fore with implications for the victims and close relations. Victims may have to leave with post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) leading to loss of concentration at work and home, alcohol dependency, hypertension, divorce, and pregnant victims could suffer miscarriage and other complications. Moreover, while information on economic/financial abuse was scanty in the articles reviewed, this form of abuse is worthy of attention. This affirms reports by UNFPA (2021a; 2021b; 2021c) that found that some men in Africa deliberately stopped providing financial support to their partners during the pandemic. Therefore, economic/financial power was weaponised by men against their partners during the pandemic in Africa. Meanwhile, all the aforementioned abuses have clear implications for the realisation of the SGDs. For instance, physical, emotional, and sexual violence vitiate Africa’s quest to attain the SDGs 3, 4.7, 5, 9, 16.1, 16.2, and 16.a.

Predictors of IPV

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and economic hardship mutually and independently predisposed people to IPV during the period under review, 2020–2022. Though, other predictors like substance abuse by perpetrators, spending more time together, and domestic duties were widely reported, the pandemic-induced economic hardship triggered and escalated these pre-existing factors. This compares favourably with existing evidence (Gordon and Sauti, 2022) that implicated the pandemic and economic hardship in the occurrence of IPV. Though, there is adequate pre-pandemic evidence (Dwarumpudi et al., 2022; Izugbara et al., 2020; Peterman et al., 2022) reporting a strong association between economic hardship and the occurrence of IPV, the current study suggests that the pandemic escalated the vulnerabilities of people to economic hardship which further triggered the high IPV incidence in Africa. Moreover, the findings of the current study also validate previous studies (Macassa et al., 2022; Tochie et al., 2020) that found SARS-CoV-2 as the main trigger of IPV. Thus, the pandemic was both a primary and secondary cause of job and income loss, increased fear, frustration, depression, and hopelessness.

Furthermore, the findings of the current study mirror previous studies (Gordon and Sauti, 2022; Izugbara et al., 2020; Peterman et al., 2022) that revealed the interdependence of the triggers of IPV and how together they worsened the exposure and limited avenues for coping by victims. However, the current study departs significantly from a previous study (Morris et al., 2020) which reported that the lockdown measures during the pandemic actually led to a reduction in the incidence of IPV in South Africa. Thus, regardless of the findings of Morris et al. (2020) reporting otherwise, the evidence that implicated SARS-CoV-2 in IPV incidence in Africa is rock solid. Therefore, governments in Africa may consider extending financial aid to victims of IPV during the pandemic.

Gender

As a social canker, both males and females suffered IPV during the SARS-CoV-2 lockdown. However, females were by far the most exposed to the pre-existing vulnerabilities to IPV which include lack of stable job, low-income status, negative socio-cultural norms, and low level of formal education. Thus, the current study coheres favourably with previous studies (Gordon and Sauti, 2022; Morris et al., 2020; WHO, 2012) that reported females as the most vulnerable to IPV during the pandemic. Similarly, the current study also affirms several pre-pandemic studies (Ekhator-Mobayode et al., 2022; Gibbs et al., 2020; Stern et al., 2020) that found females as the main victims of IPV in most societies. This raises the issues of gender equity and calls for pragmatic measures in mainstreaming affirmative action and women’s empowerment. Thus, the findings are a drawback to Africa’s effort at gender mainstreaming provided for by SDGs 4 and 5.

Impact of IPV on victims

We found that victims of the pandemic-induced IPV were affected in many ways including stress, depression, isolation, hopelessness, unwanted pregnancy, and social media addiction. However, mental health-related issues alone accounted for 50% of the reported effects of the pandemic-induced IPV on victims. This upholds findings from previous studies (Gibbs et al., 2020; Izugbara et al., 2020; Peterman et al., 2022) that reported mental health issues as the number one impact of IPV on victims. This contradicts some pre-pandemic studies (Leeper et al., 2021; Temesgan et al., 2021; Tiruye et al., 2020) that reported death, body injury, abortion and miscarriage, sexually transmitted diseases like HIV/AIDS, and divorce as impacts of IPV. However, given the limited opportunities for reporting IPV incidence during the pandemic, it was possible that the incidence of death, abortion, and other consequences of IPV that occurred were not recorded. Therefore, victims of the pandemic-induced IPV could be living with health issues that require medical attention. Moreover, the incidence of unintended pregnancies reported in the current study could lead to victims dropping out of school, attempting unsafe abortions, and sexually transmitted infections. This affirms reports by UNFPA (UNFPA, 2021a; 2021b; 2021c) that found spikes in unwanted pregnancies in Africa during the pandemic. According to the UNFPA reports, a high number of teenagers in Africa reported rape and unintended pregnancy during the pandemic. Thus, there will be a need to organised special medical screening for all victims of rape during the pandemic so as to identify and manage cases of STIs.

Coping strategies

Most of the pre-pandemic studies (Dwarumpudi et al., 2022; Gordon and Sauti, 2022) reported engagement strategies like active resistance, help-seeking, and participation in church activities as common coping strategies employed by victims of IPV. This involves victims openly confronting perpetrators verbally or exploring informal support avenues to demand a change in their behaviour. In contrast to this, the current study reported no clear-cut coping strategy employed by the victims of the pandemic-induced IPV. However, a few maladaptive strategies including extended use of social media, running away from the perpetrators, and accepting IPV as part of culture emerged in the current study. We believe that the pandemic limited the options for employing appropriate IPV coping mechanisms by the victims. Thus, given the limited coping strategies reported, some victims of IPV, females especially, may be living with PTSD that could potentially lead to alcoholism, internet addiction, attempted suicide, and prostitution. The resilience of these victims would be broken, thus leaving them more vulnerable to future IPV.

Limitations

This is the first study to have comprehensively reviewed empirical evidence on how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic influenced IPV incidence around 2020–2022 in Africa. Regardless, the review carried some limitations including (i) relying on only peer-reviewed articles written in English may have eliminated some useful studies in other languages, (ii) the use of ten articles in the review limits the literature sample and generalisability of findings, (iii) methodological and procedural limitations inherent in the reviewed articles potentially influenced the findings and conclusion reached in this review. Meanwhile, we elected to take up the study pursuant to the SDGs 5.2 and 16.1, which essentially seek to uphold affirmative action and promote women’s empowerment in Africa.

Conclusions and recommendations

We deduct that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic escalated the vulnerabilities of people to economic hardship which in turn resulted in the high incidence of IPV during 2020–2022 in Africa. Again, Ethiopia reported the highest prevalence of IPV during the pandemic, but we suggest further research from other African nations. Moreover, psychological/emotional abuse was the most prevalent form of IPV suffered, with females reporting the highest incidence. Mental health issues like stress, depression, isolation, and hopelessness were the most reported effects of IPV on victims. Thus, as a major human rights concern, the high IPV prevalence found may be undermining efforts at achieving the SDGs 2.2, 4, 5.2, 11.7, and 16 in Africa. The SDG 2.2, provides, inter alia, for an end to malnutrition of all kinds among young females and pregnant and breastfeeding women everywhere. The SDG 4 guarantees equity and inclusivity in education as a means to promoting sustainable learning avenues for all, while SDG 5 promotes gender parity and women’s employment. Again, SDG 11.7 guarantees unlimited access to safe, inclusive, and green public spaces, especially for females. Also, SDG 16 provides, inter alia, for societies of peace, justice, inclusiveness, and accountability to ensure sustainable development for all. Meanwhile, are these SDGs attainable by African countries in the phase of the current findings?

Though, few studies exist on IPV in Africa, the current study appears to be the first to have reviewed literature on how the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic influenced IPV incidence. To help mitigate the impact of the pandemic-induced IPV, we recommend that the affected countries provide adequate social support, including financial assistance, to the victims. Additionally, there is a need for public education about IPV, with emphasise on help-seeking strategies. We further suggest a recalibration of existing legal frameworks on IPV to guarantee adequate support for victims and ensure that perpetrators are brought to justice. Given the public health relevance of IPV, we suggest that a study be conducted on the efficacy of existing legal frameworks and social support structures on IPV in Africa. We further recommend that future studies compare IPV prevalence in Africa to other continents. Finally, given the high incidence of unintended pregnancies associated with the pandemic-induced IPV and their implications for SDGs 2.2, 4, 5.2, 11.7, and 16, we recommend medical screening for all victims so as to identify and manage cases of sexually transmitted infections.

Data availability

All data underlining the review provided as a supplementary file.

References

Adejimi AA, Fawole OI, Sekoni OO, Kyriacou DN (2014) Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among male civil servants in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 43(1):51–60

Anderson S (2021) Intimate partner violence and female property rights. Nat Hum Behav 5:1021–1026. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01077-w

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3:77–101

Campbell AM (2020) An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 100089. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7152912/

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2015) Prevalence of sexual violence against children and use of social services–seven countries, 2007–2013. Morbid Mortal Week Rep 64:565–569

Duncan TK, Weaver JL, Zakrison TL, Joseph B, Campbell BT, Christmas AB, Stewart RM, Kuhls DA, Bulger EM (2020) Domestic violence and safe storage of firearms in the CoVID-19 era. Ann Surg 272(2):e55–e57. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004088

Dwarumpudi A, Mshana G, Aloyce D, Peter E, Mchome Z, Malibwa D, Kapiga S, Stöckl H (2022) Coping responses to intimate partner violence: Narratives of women in North-west Tanzania. Cult Health Sexual https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2022.2042738

Ekhator-Mobayode UE, Hanmer LC, Rubiano-Matulevich E, Arango DJ (2022) The effect of armed conflict on intimate partner violence: evidence from the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. World Dev 153:105780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105780

Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, Contreras M, Watts C (2014) Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? Lancet 385:1555–1566

Fawole OI, Okedare OO, Reed E (2021) Home was not a safe haven: women’s experiences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria. BMC Women’s Health 21(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01177-9

Gebrewahd GT, Gebremeskel GG, Tadesse DB(2020) (2020) Intimate partner violence against reproductive age women during COVID-19 pandemic in northern Ethiopia 2020: a community-based cross-sectional study. Reproduct Health 17(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-01002-w

Gibbs A, Washington L, Abdelatif N, Chirwa E, Willan S, Shai N, Sikweyiya Y, Mkhwanazi S, Ntini N, Jewkes R (2020) Stepping stones and creating futures intervention to prevent intimate partner violence among young people: Cluster randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health 66:323e335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.10.004

Gordon E, Sauti G (2022) Reflections on intimate partner violence, its psycho-socio-cultural impact amidst COVID-19: Comparing South Africa and the United States. J Adult Protect 24(3/4):195–210

Gottert A, Abuya T, Hossain S, Casseus A, Warren C, Sripad P (2021) Extent and causes of increased domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: community health worker perspectives from Kenya, Bangladesh, and Haiti. J Glob Health Rep 5. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.24944

Izugbara CO, Obiyan MO, Degfie TT, Bhatti A (2020) Correlates of intimate partner violence among urban women in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 15(3):e0230508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230508

Jarnecke AM, Flanagan JC (2020) Staying safe during COVID-19: How a pandemic can escalate risk for intimate partner violence and what can be done to provide individuals with resources and support. Psychol Trauma Theor Res Pract Policy 12(S1):S202

John N, Casey SE, Carino G, McGovern T (2020) Lessons never learned: Crisis and gender-based violence. Dev World Bioethics 20(2):65–68

Leeper SC, Patel MD, Lahri S, Beja-Glasser A, Reddy P, Martin IBK, van Hoving DJ, Myers JG (2021) Assault-injured youth in the emergency centres of Khayelitsha, South Africa: A prospective study of recidivism and mortality. Afr J Emerg Med 11:379–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2021.07.001

Macassa G, Francisco JDC, Militao E, Soares JA (2022) Descriptive systematic review of food insecurity and intimate partner violence in Southern Africa. Women 2:397–407. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2040036

Mazza M, Marano G, Lai C, Janiri L, Sani G (2020) Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res 289:113046

McCloskey LA, Boonzaier F, Steinbrenner SY et al. (2016) Determinants of intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of prevention and intervention programs. Partn Abuse 7(3):277–315

Meinck F, Cluver L, Loening-Voysey H, Bray R, Doubt J, Casale M, Sherr L (2017) Disclosure of physical, emotional and sexual child abuse, help-seeking and access to abuse response services in two South African Provinces. Psychol Health Med 22:94–106

Moreira DN, Da Costa MP (2020) The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. Int J Law Psychiatry 71:101606

Morris D, Rogersa M, Kissmera N, Preeza AD, Dufourqa N (2020) Impact of lockdown measures implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic on the burden of trauma presentations to a regional emergency department in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. Afr J Emerg Med 10:193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2020.06.005

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between systematic and scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s128018-0611-x

Ojeahere MI, Kumswa SK, Adiukwu F, Plang JP, Taiwo YF (2022) Intimate partner violence and its mental health implications amid COVID-19 lockdown: Findings among Nigerian couples. J Interpers Viol 37(17-18):NP15434–NP15454. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211015213

Peterman A, Valli E, Palermo T (2022) Government antipoverty programming and intimate partner violence in Ghana. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 70(2). https://doi.org/10.1086/713767

Plan international (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on girls in Africa. Under Siege

Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C (2020) Violence against women during Covid-19 pandemic restrictions. https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1712

Sediri S, Zgueb Y, Ouanes S, Ouali U, Bourgou S, Jomli R, Nacef F (2020) Women’s mental health: acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Arch Women’s Ment Health 23:749–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01082-4

Sharma A, Borah SB (2020) Covid-19 and domestic violence: an indirect path to social and economic crisis. J Fam Violence 37(5):759–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00188-8

Shewangzaw Engda A, Dargie Wubetu A, Kasahun Amogne F, Moltot Kitaw T (2022) Intimate partner violence and COVID-19 among reproductive age women: A community-based cross-sectional survey, Ethiopia. Women’s Health (London, England) 18:17455065211068980. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455065211068980

Shitu S, Yeshaneh A, Abebe H (2021) Intimate partner violence and associated factors among reproductive age women during COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Ethiopia, 2020. Reprod Health 18(1):246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01297-3

Sikweyiya Y, Addo-Lartey AA, Alangea DO, Dako-Gyeke P, Chirwa ED, Coker-Appiah D, Adanu RMK, Jewkes R (2020) Patriarchy and gender-inequitable attitudes as drivers of intimate partner violence against women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health 20:682. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08825-z

Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, Ssentongo P, Lin D, Yang Y, Onen J, Hazelton JP, Oh JS, Chinchilli VM (2020) Domestic Violence across 30 Countries in Africa. BMJ Global Health, https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.19.20107029

Stern E, van der Heijdenb I, Dunkleb K (2020) How people with disabilities experience programs to prevent intimate partner violence across four countries. Eval Program Plann 79:101770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101770

Tadesse AW, Tarekegn SM, Wagaw GB, Muluneh MD, Kassa AM (2022) Prevalence and associated factors of intimate partner violence among married women during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions: a community-based study. J Interpers Viol 37(11-12):NP8632–NP8650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520976222

Temesgan WZ, Endale ZM, Aynalem GL (2021) Sexual violence and associated factors among female night college students after joining the college in Debre Markos town, North West Ethiopia, 2019. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 10:100689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2020.100689

Teshome A, Gudu W, Bekele D, Asfaw M, Enyew R, Compton SD (2021) Intimate partner violence among prenatal care attendees amidst the COVID-19 crisis: The incidence in Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 153(1):45–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13566

Tiruye TY, Chojenta C, Harris ML, Holliday E, Loxton D (2020) Intimate partner violence against women and its association with pregnancy loss in Ethiopia: Evidence from a national survey. BMC Women’s Health 20:192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01028-z

Tochie JN, Ofakem I, Ayissi G, Endomba FT, Fobellah NN, Wouatong C, Temgoua MN (2020) Intimate partner violence during the confinement period of the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the French and Cameroonian public health policies. Pan Afr Med J 35(2):54. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23398

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D et al. (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169:467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Tsai AC, Wolfe WR, Kumbakumba E, Kawuma A, Hunt PW, Martin JN, Bangsberg DR, Weiser SD (2016a) Prospective study of the mental health consequences of sexual violence among women living with HIV in rural Uganda. J Interpers Viol 31:1531–1553

Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ (2016b) Intimate partner violence and depression symptom severity among South African women during pregnancy and postpartum: population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 13:e1001943

Turner E, Cerna-Turoff I, Nyakuwa R, Nhenga-Chakarisa T, Muchemwa Nherera C, Parkes J, Rudo Nangati P, Nengomasha B, Moyo R, Devries K (2022) Referral of sexual violence against children: how do children and caregivers use a formal child protection mechanism in Harare, Zimbabwe? SSM Qual Res Health 2:100184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100184

Undie CC, Mathur S, Haberland N, Vieitez I, Pulerwitz J (2021) Opportunities for SGBV data collection in the time of COVID-19: the value of implementation science. Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI) blog

United Nations Population Fund (2021a) Statement of the Executive Director to the 1st regular session of the Executive board 2021. New York, United States of America. https://www.unfpa.org/press/statement-executive-director-1st-regular-session-executive-board-2021

United Nations Population Fund (2021b) Religions and women’s rights: Principled engagement and mutual accountability. New York, United States of America. https://www.unfpa.org/press/religions-and-womens-rights-principled-engagement-and-mutual-accountability

United Nations Population Fund (2021c) The power to say yes, the right to say no. New York, United States of America. https://www.unfpa.org/press/power-say-yes-right-say-no

United Nations Women (2020 a) Impact of COVID‐19 on violence against women and girls and service provision: UN Women rapid assessment and findings

United Nations Women (2020b) The shadow pandemic: violence against women during COVID-19

Wado YD, Mutua MK, Mohiddin A, Ijadunola MY, Faye C, Coll CVN, Barros AJD, Kabiru CW (2021) Intimate partner violence against adolescents and young women in sub‑Saharan Africa: Who is most vulnerable? Reprod Health 18(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01077-z

World Health Organization (2010) Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

World Health Organization (2012) Understanding and addressing violence against women. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2013) Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2016a) Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2016b) World health statistics 2016: Monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2017) Violence against women: Key facts. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2018) Violence against women Strengthening the health response in times of crisis. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2019) Respect women: Preventing violence against women. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2020 a) COVID-19 and violence against women what the health sector/system can do. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2020b) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report—131. World Health Organization, Geneva

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Flt Lt Lucy Adjanor, AKOTO, Ghana Armed Forces Medical Services, for assisting during the articles search and proofreading of the draft review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EWA, NNB, and BB conceptualised and designed the review protocols. AA and LFA-A conducted data collection and acquisition. EWA, AA, LFA-A, and NNB carried out extensive data processing and management. EWA, NNB, BB, and LFA-A developed the initial manuscript. All authors edited and considerably reviewed the manuscript, proofread for intellectual content, and consented to its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This is largely a synthesis of evidence from published articles, called scoping review.

Informed consent

This is not applicable to this study as it does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors, but rather a synthesis of evidence from published articles, called scoping review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansah, E.W., Asamoah, A., Bimpeh, B. et al. Covid-induced intimate partner violence: scoping review from Africa between 2020 and 2022. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 612 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02062-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02062-6