Abstract

The exploration of highly efficient processes to convert renewable biomass to fuels and value-added chemicals is stimulated by the energy and environment problems. Herein, we describe an innovative route for the production of methylcyclopentadiene (MCPD) with cellulose, involving the transformation of cellulose into 3-methylcyclopent-2-enone (MCP) and subsequent selective hydrodeoxygenation to MCPD over a zinc-molybdenum oxide catalyst. The excellent performance of the zinc-molybdenum oxide catalyst is attributed to the formation of ZnMoO3 species during the reduction of ZnMoO4. Experiments reveal that preferential interaction of ZnMoO3 sites with the C=O bond instead of C=C bond in vapor-phase hydrodeoxygenation of MCP leads to highly selective formations of MCPD (with a carbon yield of 70%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

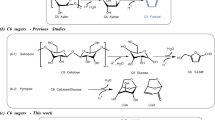

With the increment of social concern about energy and environmental problems, the exploration of technologies for the production of fuels1,2,3,4,5 and value-added chemicals6,7,8,9,10 with renewable biomass has drawn a lot of attention. Methylcyclopentadiene (MCPD) is an important monomer in the production of RJ-4 fuel, a high-energy-density rocket fuel11. Meanwhile, it is also widely used in the synthesis of various valuable products (e.g., epoxy curing agent methylnadic anhydride (MNA), gasoline antiknock methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT), medicines, dye additives, organometallic catalysts, etc.)12. Currently, MCPD is mainly obtained from the by-products of petroleum cracking tar at a very low yield (~0.7 kg ton−1) and high price (~10,000 USD ton−1)12,13. This greatly limits its application. Previous studies have shown that the linalool can be converted to MCPD14. However, linalool is extracted from some special plants (such as lavender, rose, basil, and citrus aurantium, etc.) at low yields. From a practical point of view, the route for the synthesis of renewable MCPD with cheaper and more abundant biomass is highly expected. It is well-known that cellulosic biomass has the advantage of large availability, renew-ability, and CO2 neutral. Therefore, the development of strategies for the production of MCPD with cellulose will be of considerable significance because of its increasing market demand (>50,000 tons year−1) and limited petroleum resources. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report about the selective synthesis of MCPD via chemical conversion of cellulose.

Herein, we describe an approach to produce renewable MCPD from cellulose (Fig. 1). This process is an integrated technology that includes the hydrogenolysis of cellulose to 2,5-hexanedione (HD), the intramolecular aldol condensation of HD to 3-methylcyclopent-2-enone (MCP), and subsequent hydrodeoxygenation of MCP to MCPD. The first two steps have been reported by literature15,16,17,18. In our recent work18, cellulose was selectively transformed into HD with a separation carbon yield of 71%. The intramolecular aldol condensation of the cellulose-derived HD produced MCP at a carbon yield of 98%. Based on these results, a high overall carbon yield of 70% MCP was obtained from cellulose. As the focus and innovation of this work, we reported the direct synthesis of MCPD by the selective hydrodeoxygenation of MCP.

Results

Catalytic performance of metal oxide catalysts

As we know, the direct hydrodeoxygenation of unsaturated ketones to dienes is a reaction that has great commercial significance. However, this process is usually very challenging because the hydrogenation of C=C bond in unsaturated ketones is preferred than the hydrogenation and/or cleaving of C=O bond19. In the recent work of Román-Leshkov et al.20, a series of saturated ketones and aldehydes were hydrodeoxygenated to corresponding mono-olefins (or aromatics) over various slightly reducible metal oxides (e.g., V2O5, MoO3, WO3, Fe2O3, and CuO). Among them, MoO3 exhibited the highest hydrodeoxygenation activity. It has been suggested that the hydrodeoxygenation of ketones to olefins over MoO3 follows a reverse Mars–van Krevelen mechanism, which includes the reaction of oxygen vacancy sites with the oxygenates to yield olefinic products and the regeneration of oxygen vacancy sites by H2 reduction21. Unfortunately, it was found that the pure MoO3 is not well suited for selective hydrodeoxygenation of MCP to MCPD. As we can see from Table 1 (entry 1), MoO3 catalyst suffers from a poor MCPD selectivity (18%) as a result of the excessive hydrogenation of C=C bond and the C−C bond cleavage to form various by-products (such as methylcyclopentene (MCPE), hexadienes (HDE), hexenes (HE), etc.) (Supplementary Figs. 1–6). However, it is interesting that MCPD selectivity can be improved after loading MoO3 on some often used supports (e.g., ZnO, Al2O3, ZrO2, and SiO2) by the impregnation method (Table 1, entries 2–5). Meanwhile, such a promotion effect is more evident when the commercial nano-ZnO with a specific Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area of 22 m2 g−1 is used as the support. Over the MoO3/ZnO catalyst, 71% MCPD selectivity was attained at a 99% MCP conversion under the optimum reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 2 and Supplementary Fig. 8). As we can see from the H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) profiles (Supplementary Fig. 7), MoO3/ZnO exhibited the highest reduction temperature among the investigated catalysts. Therefore, we believe that the significantly higher MCPD selectivity over the MoO3/ZnO may be attributed to the strong interaction between MoO3 and ZnO support. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the synthesis of MCPD via the direct hydrodeoxygenation of MCP from cellulose. Meanwhile, this work also opens up a horizon for the production of dienes with unsaturated ketone by a direct hydrodeoxygenation process.

For comparison, we also studied the catalytic performances of ZnO supported V2O5, WO3, Fe2O3, and CuO catalysts under the same reaction conditions (Table 1, entries 6–9). It was noticed that the MCP conversions and MCPD carbon yields over the V2O5/ZnO, WO3/ZnO, Fe2O3/ZnO, and CuO/ZnO catalysts are obviously lower than those over the MoO3/ZnO catalyst. Due to this reason, we concentrated on the MoO3/ZnO catalyst in the following research.

Relationship between catalyst structure and activity

To find out the intrinsic reason for the excellent catalytic performance of MoO3/ZnO, we investigated the structure evolution of the Mo species during the preparation of the MoO3/ZnO catalyst. For the MoO3/ZnO catalyst precursor prepared by the impregnation of ZnO with ammonium heptamolybdate (AHM) solution, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns show well-resolved peaks corresponding to the H3NH4Zn2Mo2O10 species, as well as ZnO (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 9). Upon calcination at 600 °C, the characteristic peaks associated with H3NH4Zn2Mo2O10 disappeared, indicating the decomposition of H3NH4Zn2Mo2O10 to ZnMoO4 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 10). No obvious MoO3 peak was detected in both the XRD patterns and Raman spectra of MoO3/ZnO catalyst (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). The X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectrum at the K-edge of Mo species in the catalyst exhibits the same characteristics of reference ZnMoO4 compound (Fig. 2b), which is different from the AHM and MoO3 compounds. These results confirm that the Mo species exists mainly as the ZnMoO4 phase on the ZnO support. After contacting with hydrogen under the reaction temperature of 400 °C, the XRD pattern showed that the ZnMoO4 peaks disappeared. Meanwhile, the ZnMoO3 peaks appeared at 18.1° and 29.7° (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 12). This result means that ZnMoO4 was gradually transformed into ZnMoO3 under reaction condition. The XANES spectra at the K-edge of Mo species in Fig. 2c indicated that the valance state of the Mo species in the reduced sample was close to that of the MoO2. At the same time, the peak at the pre-edge (~20,005 eV) ascribed to the distorted octahedral structure in the MoO3 sharply decreased, which indicated the structure of Mo species changed to the octahedral structure22,23. The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) data in r-space (Supplementary Fig. 13) and the data fitting results (Supplementary Table 1) showed that the average Mo-O distance in the first shell of the reduced 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO is 2.06 Å, which is longer than those in the MoO2 (2.02 Å) and the reduced MoO3 (2.01 Å). Besides, the corresponding coordination number of the Mo-O of the reduced 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO is 4.3, which is lower than that of the reduced MoO3 (4.8). The above results indicated that the interaction between the MoOx and ZnO leads to the expansion of the Mo-O distance and reduction of the Mo-O coordination in the first shell. The specific BET surface area of the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO was measured as 19.2 m2 g−1, which is very close to that of ZnO support (Supplementary Table 2). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) shows that the Mo species are uniformly dispersed on the ZnO nanoparticles (Fig. 2d).

a XRD patterns of the as-prepared (blue line), calcined (black line), and reduced (red line) 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalysts. b Normalized XANES spectra at the K-edge of Mo of the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst and three reference compounds (ZnMoO4, MoO3, and AHM). c Normalized XANES spectra at the K-edge of Mo of the reduced MoO3, 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst and two reference compounds (MoO3 and MoO2). d STEM image and elemental mappings of the reduced 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst. e TG profiles of the reduced MoO3 and 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalysts in flowing air. f Mo 3d core level XPS spectrum of the reduced MoO3 and 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalysts. 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO represents that the mass of Mo element in the catalyst accounts for 15% of the total mass.

For the deoxygenation catalyzed by the slightly reducible oxides, it is generally accepted that the oxy-compound is adsorbed on the oxygen vacancies of metal oxides20. Since the dissociation of C=O bonds is a high barrier process, the oxygen vacancy concentrations of the oxides will directly decide their catalytic performances in the deoxygenation reaction. The degree of generating oxygen vacancies for the oxides after reduction for 2 h were evaluated by thermogravimetry (TG) in flowing air (Fig. 2e). The percentage of weight gain for the partially reduced 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO and MoO3 were measured as 2.261% and 1.988%, respectively. From this result, we can see that the oxygen vacancy concentration of 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO is higher than that of MoO3. The interaction between the MoOx and ZnO might promote the formation of the oxygen vacancies, as manifested by the EXAFS results in Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 1: the distance and the coordination number of Mo-O in the first shell of the reduced 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO are longer and lower respectively than the corresponding parameters of the reduced MoO3. If we calculated based on Mo species (In this calculation, the contribution of ZnO support was excluded because the oxygen vacancies generated by ZnO were negligible under conditions employed (Supplementary Fig. 14)), the oxygen vacancy concentrations of 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO (10.049%) is ~5 times that of MoO3 (1.988%). This may be the reason why 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst is more selective for the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP to MCPD than bulk MoO3 (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).

To further find out the reason for the high MCPD selectivity in the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst, the electronic properties of surface Mo species of the partially reduced catalyst were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Fig. 2f). The peak fitting suggests that there are three oxidation states (+4, +5, and +6) for Mo species on the surface of 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst24,25. Mo6+ is derived from unreduced ZnMoO4. Small Mo5+ peaks along with the dominant peaks of Mo4+ can be assigned to the partially-reduced ZnMoO4 moieties and the coordinatively unsaturated sites of ZnMoO3, respectively. Compared with the binding energies (BE) of Mo4+ in the reduced MoO3 (229.5 eV), the higher BE in the reduced 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO (230.0 eV) indicates the lower electron density of Mo species, which may hinder the hydrogenation of C=C bond and C−C bond cleavage in the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP, consequently lead to the higher MCPD selectivity (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).

Preferential adsorption of C=O bond on catalyst

In addition to the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP, we also examined the hydrogenation of MCPD over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO, MoO3, and ZnO catalysts to further illustrate how the electronic properties of catalysts influence their behaviors. As shown in Fig. 3a, ZnO support was almost inactive for the hydrogenation of MCPD under the investigated conditions. In contrast, both 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO and MoO3 are highly active for the hydrogenation of MCPD. Over them, high MCPD conversions were observed, MCPE was formed as the major product (the conversions of MCPD over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO and MoO3 are 81% and 98%, while the corresponding selectivities of MCPE are 59% and 49%, respectively). Based on this result, we cannot simply attribute the higher MCPD selectivity of MoO3/ZnO to its lower activity for the C=C bond hydrogenation during hydrodeoxygenation of MCP. Taking into consideration that MCP has C=C bond and C=O bond simultaneously, we believe that the higher selectivity for deoxygenation of MCP to MCPD over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst might be the result of energetically preferential adsorption of C=O bond in presence of C=C bond. To verify this hypothesis, acetone (a biomass-derived ketone, which has C=O bond) was co-fed with MCPD over 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO, MoO3, and ZnO. As shown in Fig. 3b, the co-feeding of acetone had no evident influence on the MCPD conversion over MoO3, which means that MoO3 catalyst remains highly active for hydrogenation of C=C bond in MCPD even in presence of C=O bond (from acetone). In contrast, the presence of acetone significantly restrained the hydrogenation of MCPD over 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO. This may be one reason for the higher MCPD selectivity over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst for MCP hydrodeoxygenation.

In addition to acetone, the reaction with MCPD + 4-hexen-3-one (a representative of α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compound) as a reactant was investigated over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, the presence of 4-hexen-3-one significantly restrained the hydrogenation of MCPD, leading to a decrease of MCPD conversion from 79 to 17%. The phenomenon is similar to what we observed when MCPD + acetone was used as a feedstock. As we know, MCP also has C=O group. Its preferential adsorption over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst may prevent the further hydrogenation of MCPD (generated from the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP) to MCPE. As the result, a high MCPD yield (or selectivity) was achieved over the MoO3/ZnO catalyst. On the contrary, there is no such preferential adsorption over the MoO3, which may be attributed to the lower Mo BE on partially reduced MoO3/ZnO than that on partially reduced MoO3 as indicated by XANES and XPS results from Fig. 2c, f, Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 1. As the result, the MCPD selectivity over MoO3 is lower than that over MoO3/ZnO.

To further simplify technology for the synthesis of MCPD with cellulose, HD (obtained by the direct hydrogenolysis of cellulose) and H2 were also used as a feed to directly produce MCPD under the same conditions as we used for the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP. Over the optimized 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst, 42% MCPD selectivity was attained at a 99% HD conversion (Table 1, entry 16). This result means that the intramolecular aldol condensation of HD to MCP and the subsequent selective hydrodeoxygenation of MCP to MCPD can be integrated into a one-step process, which is advantageous in a real application. To further confirm this hypothesis, we also studied the aldol condensation of HD to MCP over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst using N2 as the carrier gas. Under the same conditions as we used for the conversion of HD to MCPD under H2 atmosphere, a 70.5% selectivity of MCP was achieved at a 53.5% HD conversion (Supplementary Table 3). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report about the direct synthesis of a cyclic diene with straight-chain diketone as well.

Stability of the catalyst

Finally, we also checked the stability of the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst. During the 20 h time on steam (Fig. 4), the MCPD selectivity over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst kept constant, while the MCP conversion over the 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst slightly decreased. Fortunately, such a problem can be overcome by regeneration. After being in situ calcined at 500 °C for 2 h in flowing air and then reduced at 400 °C in H2 flow for 2 h, the catalytic activity of deactivated MoO3/ZnO catalyst was almost restored to its initial level. Based on Supplementary Fig. 16, the spent 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst shows similar XRD patterns as the fresh one (after in situ reduction under the reaction conditions), which may be the reason for the stable MCPD selectivity over the MoO3/ZnO catalyst. The deactivation of MoO3/ZnO catalyst may be attributed to the formation of coke during the reaction because of the notable weight loss during calcination at high-temperature region (380–500 °C) indicated by TG in flowing air (Supplementary Fig. 17).

In summary, we have demonstrated a facile route for the synthesis of MCPD from cellulose. Firstly, MCP was obtained at 70% overall carbon yield from cellulose via our reported method. Subsequently, as the innovation of this work, MCPD was selectively obtained by the direct hydrodeoxygenation of MCP over a 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst. Based on the characterization results, the excellent performance of MoO3/ZnO catalyst could be ascribed to the formation of ZnMoO3 sites, which may preferentially adsorb C=O bond in the presence of C=C bond. As the result, a high yield of MCPD was obtained by the hydrodeoxygenation of MCP over the MoO3/ZnO catalyst. This work enables the synthesis of renewable MCPD with cheap and abundant cellulose from a practical point of view.

Methods

Materials

Analytical-grade 3-methylcyclopent-2-enone (MCP, 97%) and ammonium heptamolybdate ((NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, 99%) were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. and Tianjin Kermel Chemical Reagent Co, respectively. Commercially available nano-ZnO (ca. ~20 nm) were supplied by Nanjing Xianfeng nanometer material technology Co. LTD. Al2O3, ZrO2, and SiO2 supports were supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. The methylcyclopentadiene dimer (93%) supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. was used for calibration after distilled under 160–170 °C.

Preparation of catalysts

The xMoO3/ZnO (x denotes the theoretical Mo loading in weight percentage), 15wt.%MoO3/Al2O3, 15wt.%MoO3/ZrO2, and 15wt.%MoO3/SiO2 catalysts were prepared by the impregnation method. A typical procedure was as follows: A defined amount of supports (e.g., ZnO, Al2O3, ZrO2, and SiO2) were added into an aqueous solution of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O. The mixture was stirred for 4 h, dried at 120 °C for 4 h, and calcined at 400‒700 °C for 1 h in flowing air. The MoO3 catalyst was prepared by the calcination of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O at 600 °C for 1 h in flowing air.

Activity test

The hydrodeoxygenation of 3-methylcyclopent-2-enone (MCP) was carried out under atmospheric pressure in a fixed-bed reactor. The diagram of the reaction device used in MCP hydrodeoxygenation is shown in Supplementary Fig. 18. The tubular reactor used in this work was made of 316 L stainless steel. The length, inner diameter, and constant temperature height of the reactor were measured as 30, 0.5, and 10 cm, respectively. For each test, 2.5 g of catalyst was used. The static bed layer height was measured as 2 cm. Prior to the activity test, the catalysts were activated by hydrogen (at a gas flow rate of 90 mL min−1) at 400 °C for 2 h, and then MCP (at a liquid flow rate of 0.01 mL min−1) was introduced into the reactor by HPLC pump along with H2 (at a gas flow rate of 90 mL min−1) which acted as a reactant and carrier gas at the same time. The contact time of MCP on the catalysts was calculated as 42.67 s.

The products passed through the reactor, cooled down to 0 °C, and became two phases in a gas-liquid separator. A small number of gas-phase products such as methylcyclopentadiene (MCPD), methylcyclopentene (MCPE), hexadienes (HDE), and hexenes (HE), were analyzed on-line by an Agilent 7890B GC after passing through the back pressure regulator. According to the concentration of feed (or specific compound) in the gas-phase effluent products (measured with the on-line GC by an external standard method), the gas flow rate of the effluent gas, and reaction time, we calculated the mole amount of feed (or specific compound) in gas-phase products. The liquid-phase products such as MCPD, MCPE, 3-methylcyclopentanone (MCPO), HDE, and hexenes HE were periodically drained from the separator and analyzed by a GC (Agilent 7890 A) fitted with a 30 m HP-5 capillary column and an FID using 1,4-dioxane as the internal standard. According to the analysis results, we calculated the mole amount of feed (or specific compound) detected in the liquid-phase products. Thus, the conversion and selectivity of the reactions were calculated based on the analysis of gas-phase and liquid-phase products. The Agilent 6540 Accurate-MS spectrometer (Q-TOF) was used for products (e.g., methylcyclopentadiene (MCPD), methylcyclopentene (MCPE), 3-methylcyclopentanone (MCPO), hexadienes (HDE) and hexenes (HE)) identification. The conversion and the selectivity of the reactions were calculated based on the following equations: Conversion (%) = 100 − total mole amount of feed detected in gas-phase and liquid-phase products/mole amount of feed pumped into reactor × 100; Selectivity for a specific compound (%) = total mole amount of a specific compound detected in the gas-phase and liquid-phase products/total mole amount of feed converted × 100.

Characterization of catalysts

XRD patterns were obtained on a PANalytical X’Pert-Pro diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at room temperature. Data points were acquired by step scanning at a rate of 10° min−1 from 2θ = 10°–90°. XRD patterns of reduced samples were tested by an in situ device. N2-physisorption tests of the investigated catalysts were carried out by an ASAP 2010 apparatus. Specific surface areas of the investigated catalysts were calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Average pore volumes and average pore sizes of catalysts were estimated according to the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the samples were collected by a JEM-2100F high-resolution transmission which was operated at 200 keV. Characterizations of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were conducted on an ESCALAB250xi spectrometer. Prior to the measurements, each sample was pressed into a thin disk and reduced under H2 flow at 400 °C in an auxiliary pretreatment chamber. After the reduction, the obtained sample was directly introduced into the XPS chamber to avoid exposure to air. The XPS spectra were recorded at room temperature. The X-ray absorption spectra including X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) at the K-edge of Mo of the samples were collected at the BL 14W1 of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), China. The Mo foil was employed to calibrate the energy. The reduced samples were sealed in the glove box to protect them from contacting air. The spectra were collected at transmission mode at room temperature. The Athena software package was used to analyze the data. H2-temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) tests were carried out using a Micromeritics Autochem II 2920 automated chemisorption analyzer which was connected with an online mass spectrometer (MKS Cirrus 2). 0.1 g of sample was firstly calcined in air at 400 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the sample was cooled down in airflow to 30 °C. Finally, the sample was heated from 30 °C to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 in diluted hydrogen flow (10% H2 in Ar, 30 mL min−1). Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis of MoO3 and 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalysts were carried out by the TA Instrument SDT Q 600 according to the following procedure. For the fresh MoO3 and 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst, the sample was reduced in hydrogen at 400 °C for 2 h and swept with Ar flow at that temperature for 0.5 h. Subsequently, the sample was cooled down to 30 °C in flowing Ar. Finally, the reduced sample was heated in flowing air (100 mL min−1) from 30 °C to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1. For the used 15wt.%MoO3/ZnO catalyst (reaction conditions: T = 400 °C, PH2 = 0.1 MPa, WHSV = 0.23 g g−1 h−1, initial H2/MCPD molar ratio = 40, time on stream = 20 h), the sample was directly heated in flowing air (100 mL min−1) from 30 to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information and all data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Huber, G. W., Iborra, S. & Corma, A. Synthesis of transportation fuels from biomass: Chemistry, catalysts, and engineering. Chem. Rev. 106, 4044–4098 (2006).

Shylesh, S., Gokhale, A. A., Ho, C. R. & Bell, A. T. Novel strategies for the production of fuels, lubricants, and chemicals from biomass. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2589–2597 (2017).

Huber, G. W., Chheda, J. N., Barrett, C. J. & Dumesic, J. A. Production of liquid alkanes by aqueous-phase processing of biomass-derived carbohydrates. Science 308, 1446–1450 (2005).

Cao, Z., Dierks, M., Clough, M. T., Daltro de Castro, I. B. & Rinaldi, R. A convergent approach for a deep converting lignin-first biorefinery rendering high-energy-density drop-in fuels. Joule 2, 1118–1133 (2018).

Dong, L. et al. Breaking the limit of lignin monomer production via cleavage of interunit. Carbon Carbon Link. Chem. 5, 1521–1536 (2019).

Besson, M., Gallezot, P. & Pinel, C. Conversion of biomass into chemicals over metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 114, 1827–1870 (2014).

Roman-Leshkov, Y., Barrett, C. J., Liu, Z. Y. & Dumesic, J. A. Production of dimethylfuran for liquid fuels from biomass-derived carbohydrates. Nature 447, 982–985 (2007).

Scodeller, I. et al. Synthesis of renewable meta-xylylenediamine from biomass-derived furfural. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10510–10514 (2018).

Deng, W. et al. Catalytic amino acid production from biomass-derived intermediates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5093–5098 (2018).

Liao, Y. et al. A sustainable wood biorefinery for low–carbon footprint chemicals production. Science 367, 1385 (2020).

Zhang, X., Pan, L., Wang, L. & Zou, J.-J. Review on synthesis and properties of high-energy-density liquid fuels: hydrocarbons, nanofluids and energetic ionic liquids. Chem. Eng. Sci. 180, 95–125 (2018).

Lan, D. et al. Methylation of cyclopentadiene on solid base catalysts with different surface acid–base properties. J. Catal. 275, 257–269 (2010).

Claus, M. et al. ULLMANN’S Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 1–16 (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2016).

Meylemans, H. A., Quintana, R. L., Goldsmith, B. R. & Harvey, B. G. Solvent-free conversion of linalool to methylcyclopentadiene dimers: a route to renewable high-density fuels. ChemSusChem 4, 465–469 (2011).

Chambon, F. et al. Conversion of cellulose to 2,5-hexanedione using tungstated zirconia in hydrogen atmosphere. Appl. Catal. A 504, 664–671 (2015).

Sun, D. L., Chiba, S., Yamada, Y. & Sato, S. Vapor-phase intramolecular aldol condensation of 2,5-hexanedione to 3-methylcyclopent-2-enone over ZrO2-supported Li2O catalyst. Catal. Commun. 92, 105–108 (2017).

Nishimura, S., Ohmatsu, S. & Ebitani, K. Selective synthesis of 3-methyl-2-cyclopentenone via intramolecular aldol condensation of 2,5-hexanedione with γ-Al2O3/AlOOH nanocomposite catalyst. Fuel Process. Technol. 196, 106185 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Integrated conversion of cellulose to high-density aviation fuel. Joule 3, 1028–1036 (2019).

Gallezot, P. & Richard, D. Selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Catal. Rev. Sci. Eng. 40, 81–126 (1998).

Prasomsri, T., Nimmanwudipong, T. & Roman-Leshkov, Y. Effective hydrodeoxygenation of biomass-derived oxygenates into unsaturated hydrocarbons by MoO3 using low H2 pressures. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 1732–1738 (2013).

Mars, P. & van Krevelen, D. W. Oxidations carried out by means of vanadium oxide catalysts. Chem. Eng. Sci. 3, 41–59 (1954).

Ressler, T., Wienold, J., Jentoft, R. E. & Neisius, T. Bulk structural investigation of the reduction of MoO3 with propene and the oxidation of MoO2 with oxygen. J. Catal. 210, 67–83 (2002).

Patridge, C. J., Whittaker, L., Ravel, B. & Banerjee, S. Elucidating the influence of local structure perturbations on the metal–insulator transitions of V1–xMoxO2 nanowires: mechanistic insights from an X-ray absorption spectroscopy study. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 3728–3736 (2012).

Bara, C. et al. Aqueous-phase preparation of model HDS catalysts on planar alumina substrates: support effect on Mo adsorption and sulfidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15915–15928 (2015).

Nolte, M. W., Saraeian, A. & Shanks, B. H. Hydrodeoxygenation of cellulose pyrolysis model compounds using molybdenum oxide and low pressure hydrogen. Green. Chem. 19, 3654–3664 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 21776273; 21721004; 21690082), DICP (Grant: DICP I201944), DNL Cooperation Fund, CAS (DNL180301), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB17020100), the National Key Projects for Fundamental Research and Development of China (2016YFA0202801). The authors also appreciate the help from BL 14W beamline at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), Shanghai, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and R.W. contributed equally to this work. Y.L. and R.W. performed the catalyst preparation, characterizations, and activity tests. H.Q. collected the EXAFS data. X.L., G.L., A.W., X.W., and Y.C. analyzed the results. N.L. and T.Z. conceived the overall direction of the project. Y.L., N.L., and T.Z. co-wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results and provided input for the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Satoshi Sato, Lauri Vares and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Wang, R., Qi, H. et al. Synthesis of bio-based methylcyclopentadiene via direct hydrodeoxygenation of 3-methylcyclopent-2-enone derived from cellulose. Nat Commun 12, 46 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20264-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20264-3

This article is cited by

-

Efficient selective activation of sorbitol C–O bonds over C–C bonds on CoGa (221) generated by lattice-induction strategy

Nano Research (2023)

-

Solvent-free dehydration, cyclization, and hydrogenation of linalool with a dual heterogeneous catalyst system to generate a high-performance sustainable aviation fuel

Communications Chemistry (2022)

-

One-dimensional titanate nanotube materials: heterogeneous solid catalysts for sustainable synthesis of biofuel precursors/value-added chemicals—a review

Journal of Materials Science (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.