Abstract

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC-GT) is becoming increasingly widespread. The aim of this research was to systematically review the literature published on healthcare professionals’ knowledge and views about DTC-GT, as an update to a 2012 systematic review. The secondary aim was to assess the knowledge and views of healthcare professionals on the ethical and legal issues pertaining to DTC-GT. A systematic search was performed to identify all relevant studies that have been conducted since 2012. Studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria if they were primary research papers conducted on healthcare professionals about their knowledge and views on health-related DTC-GT. PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Medline databases were searched from 2012 to May 2021. Title and abstract were screened, and full texts were reviewed by two study authors independently. New papers included were appraised and data were extracted on study characteristics, knowledge and views on DTC-GT, and ethical and legal issues. A narrative synthesis was conducted. Nineteen new papers were included, along with eight papers from the previous review. There was considerable variation in study participants with differing views, awareness levels, and levels of knowledge about DTC-GT. Genetic counsellors and clinical geneticists generally had more concerns, experience, and knowledge regarding DTC-GT. Ten ethical concerns and four legal concerns were identified. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge and experience of DTC-GT, including awareness of DTC-GT ethical and legal concerns, have only minimally improved since the previous review. This emphasises the need for further medical learning opportunities to improve the gaps in knowledge amongst healthcare professionals about DTC-GT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The field of genetics has expanded exponentially in recent years, with consumer-oriented and commercially available genetic tests increasingly prevalent in the last two decades [1]. A genetic test that is offered and advertised by companies directly to the consumer, without the involvement of a conventional healthcare system, is known as direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC-GT) [2]. These tests require the consumer to provide a biological sample containing DNA (such as saliva, cells from a cheek swab or a blood sample), which is then sent by the consumer to the DTC-GT company, who perform laboratory testing on the sample to provide genetic-related information such as genetic health risks, cancer risks, and pharmacogenomics. Consumers can access companies offering DTC-GT outside of their country of residence and with considerable variation in country-specific regulations surrounding DTC-GT, regulating DTC-GT is a difficult task for policymakers [3].

Further, there has been ongoing debate about the clinical utility and clinical validity of DTC-GT, along with the ethical, legal, and social issues DTC-GTs pose. In addition to regulatory concerns, most commercially available genetic tests are not scientifically validated and can give inaccurate results [3, 4]. Results are often inconsistent between different companies and genetic testing performed using DTC-GTs have shown to be of poor predictive value [4]. Most DTC-GT involves screening for single gene and multifactorial gene disorders, however, DTC-GTs currently available may only screen for a limited number of genetic variants which may not be applicable to specific populations [5]. It is also important to note that DTC-GT companies offer screening rather than diagnostic tests, meaning DTC-GTs cannot confirm a medical condition but can be used to screen for a specific disease. Although companies do not claim DTC-GTs should be used as a substitute for seeking medical advice or be used to make medical decisions, lack of sufficient genetic services and long wait-times may be factors acting in opposition to this claim [6]. With minimal regulation and increased use of and access to DTC-GT [5], it is essential that healthcare providers have knowledge of DTC-GT, their potential role in clinical practice, and the legal and ethical issues they pose.

Studies focused on healthcare professionals’ (HCPs) knowledge and views about DTC-GT were last systematically reviewed and synthesised in 2012 by Goldsmith et al. where the authors identified considerable variation in health professionals’ views on the concerns surrounding the potential value of DTC-GT [7]. Since the time of this publication, the industry of DTC-GT has continued to grow and new evaluations of HCPs’ knowledge and views on DTC-GT have been performed [4]. This updated review aimed to expand on the work completed by Goldsmith et al. by identifying additional studies on HCPs’ knowledge and views on DTC-GT that have been published since 2012, and analysing perspectives on ethical and legal issues regarding DTC-GT that were highlighted by HCPs.

Methods

The methods of this updated review were reflective of the previous systematic review on this topic by Goldsmith et al. [7]. This review was not registered, and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 expanded checklist [8].

Information sources, search strategy, and data collection

This review used PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO (now known as APA PsycInfo) and Medline. The latter three databases were accessed via the EBSCOhost platform. A hand search of the full reference lists of all the included papers was performed so that additional relevant studies could be included. The following search strategy was created for this review: (Direct-to-consumer OR personal genom*) AND (health* professional* OR physician*) AND (genet*[tiab] OR genom* [tiab]) AND (view* OR perception* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR experience* OR opinion* OR belief* OR feel OR perspective* OR awareness). The addition of terms to the search strategy of Goldsmith et al. increased the specificity of the search by narrowing down the number of papers retrieved in the search without excluding relevant papers. Searches were conducted for the period January 2012 until May 2021, as an update to the search period of Goldsmith et al. (January 2001–July 2012).

The Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type (SPIDER) tool was used in formulating the eligibility criteria [9] given the research question was not focussed on intervention effectiveness and qualitative or quantitative research would be relevant. Studies included were determined by the eligibility criteria set out in Table 1. There were no restrictions as to study setting. Only studies reported in the English language were included, however this is unlikely to impact the overall conclusion of this review [10].

Data management

Database search results were uploaded to Rayyan. Duplicate recorded identified by Rayyan were reviewed manually and deleted (MM). Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility independently in duplicate by two study authors (MM and LT) using the blinding function in Rayyan. Any conflicts were resolved in discussion with a third reviewer (FM). Similarly, full-text records were reviewed independently in duplicate (MM and LT), with conflicts resolved with a third reviewer (FM). Records excluded at the full-text stage were recorded with the reasons for their ineligibility. One author (MM) hand-searched the reference lists of included papers and relevant systematic reviews found during the screening phase to identify eligible studies, in discussion with a second author (FM).

Data extraction and items

One author (MM) extracted data from the included studies, using a data extraction sheet (Microsoft Excel) that was piloted. Given the extracted data largely consisted of text rather than numerical data, a second reviewer (FM) verified 20% of extracted data. The following study characteristics were extracted: main author and year of publication, country of study, study aim, response rate in percentage, number and type of participants and disease/type of DTC-GT identified.

The main findings relevant to the updated systematic review were extracted from all the new papers identified, including findings related to HCPs’ awareness, knowledge, experience, and beliefs and/or opinions, findings about downstream costs and referrals and findings on genetic counsellors’ (GCs) opinions of their roles. As an extension to the Goldsmith et al. review, data were also extracted about any ethical and/or legal issues from the papers identified in the previous review and from new papers identified.

Risk of bias in individual studies

New papers identified were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Appraisal Tool for Qualitative Studies instead of the Kmet tool used by Goldsmith et al. which uses scales to calculate a single number to reflect risk of bias [11]. The CASP tool covers the same domains as are included by the Kmet tool, and so appraisals of new papers are likely comparable to those included in the previous review. The CASP Qualitative Studies tool was selected as it would accommodate the variety of study design types (i.e. mixed methods studies, surveys) with minor adaptation of question 2 to “Is the methodology appropriate?”. Studies were appraised by one author (MM), while a second author (FM) verified 20% of the ratings [12].

Narrative synthesis

A narrative synthesis was performed of the 25 studies identified for inclusion. Given the heterogeneous nature of the knowledge and views of focus in various studies and limited quantitative data, a meta-analysis was not performed [7]. The main findings identified in the new papers were analysed deductively using the same themes identified by Goldsmith et al. [7]. DTC-GT awareness, knowledge and experiences; DTC-GT beliefs and opinions; downstream costs and referrals due to DTC-GT; and GCs’ views of their roles in DTC-GT. DTC-GT beliefs and opinions were divided into six additional sub-themes. Data on ethical and legal issues from all studies were tabulated, grouped into themes, and compared. The four principles approach was used in analysing ethical issues [13, 14]. Various professional guidelines/legal regulations were used in analysing legal issues, including the General Data Protection Regulation (Europe), the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA, USA), the Council of Europe’s ‘Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine’, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations on DTC-GT [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Results

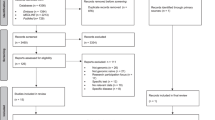

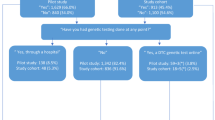

A total of 1411 records were retrieved from the databases. Of these, 308 duplicates were removed, resulting in 1103 records for title and abstract screening. Following exclusion of ineligible records, 25 full texts were reviewed, of which 17 papers met the eligibility criteria (details of 8 excluded full texts are provided in Appendix A). Two additional papers from other sources were found to fulfil the criteria for inclusion [21, 22]. Therefore, 19 new papers were identified in this review. Including the eight reports identified in the 2012 review [7] this updated systematic review identified 27 reports. Further details on study screening processes can be found in the flow diagram Fig. 1. There were two instances where two reports related to the same study (two newly identified records [22, 23], and two identified by Goldsmith et al. [7]. Therefore, this review identified a total of 25 studies that address the knowledge and views of HCPs on DTC-GT for further evaluation. The appraisal of the new studies informed by PRISMA 2020 is included in Fig. 2.

The PRISMA diagram* depicts our study selection process which includes the previous studies identified and the identification of new studies via databases, registers and other methods [8].

Evaluation of each included study based on the nine criteria included in the CASP Qualitative studies tool [12].

Study characteristics

The main characteristics of the 18 new studies, covered in 19 reports, are included in Table 2. Of these, fourteen studies were conducted in North America, either in the USA, Canada, or both [21, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Two studies were conducted in Europe and involved HCPs from several European countries [2, 22, 23]. One study was conducted in New Zealand [37], and one in Thailand, the only one conducted in a low-to-middle income country [38].

Sixteen studies used survey methods, of which eleven were online [2, 24, 26, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], three by mail [21, 28, 37], one on paper [38], and one used both mail and on paper [25]. Two studies involved focus groups [25, 27], one with a pre- and post-focus group survey [25], and one used semi-structured interviews [22, 23].

The response rates in the survey-based studies varied considerably. Eight studies had less than a 20% response rate [26, 29,30,31,32, 34,35,36], six studies had between 21 and 50% response rate [2, 21, 24, 28, 33, 37], and one study had a response rate of 60% [38]. Similarly, participant numbers varied across the survey-based studies; six had less than 200 participants [2, 26, 29, 32, 35, 37], six studies had between 201 and 500 participants [21, 28, 30, 34, 36, 38], one study had 502 participants [24], and two studies had more than 1000 participants [31, 33]. The two focus group studies had 24 and 51 participants, and the semi-structured interview study had 15 participants [22, 23, 25, 27].

The types of participants involved in these studies were diverse. Participant groups from each study were divided into one or more of the following categories: (1) medical specialists, (2) GCs, (3) clinical geneticists (CGs), and (4) primary care physicians (PCPs), including a small number of registered nurses, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Twelve studies involved PCPs [21, 24, 25, 27,28,29, 31, 33,34,35, 37, 38]. Four studies had medical specialists in their participant groups: one study involved psychiatrists and neurologists [36], one study involved urologists [25], and two involved a small number of other medical specialists [21, 34]. Five studies involved GCs [26, 30, 32, 34, 35]. Two studies involved only CGs as participants [22, 23, 35] and one study had CGs represent 1.5% of their participant group [34]. The two studies that only involved CGs were both conducted in Europe.

Regarding risk of bias, the included reports were of good quality (see Fig. 2). Six of the 19 papers had at least one issue, the most common being that the relationship between the researcher and the participants was not adequately considered, followed by the research design not being appropriate to address the aims of the research.

Main findings

The main findings identified in each of the new papers are included in Appendix B. These findings have been divided into the same four themes identified by Goldsmith et al.

DTC-GT awareness, knowledge, and experiences

Awareness

Awareness of DTC-GT was understandably higher amongst genetic specialists (GCs and CGs) compared with other HCPs. Over 95% of GCs had heard of DTC-GT before taking part in a study conducted in the US [32]. Eighty-six per cent of CGs were aware of DTC-GT services. Sixty-four per cent of those aware of these services could name at least one company that offered them [2]. Forty-eight per cent of general practitioners in New Zealand had heard about DTC-GT [37]. Fifteen per cent of internal medicine physicians in Thailand were aware of DTC-GT [38]. Related to specific DTC tests, 50% of urologists and PCPs had not heard of or read about DTC-GT for prostate cancer [25] and only 23% (n = 7) of the participants in a Canadian study were aware that patients interested in DTC-GT were able to receive counselling and other services in their healthcare facilities [35].

Knowledge

Knowledge and confidence about DTC-GT was higher amongst HCPs specialising in genetics when compared with other HCPs. This was, however, not consistent throughout the studies. Seventy-four percent of a group of PCPs versus 83% of genetic specialists were able to correctly interpret DTC-GT results [34]. Fifty-eight per cent of these PCPs versus 95% of genetic specialists agreed or strongly agreed that that they were able to understand and discuss genetics related information, and 46% versus 86% were somewhat prepared or well prepared to discuss DTC-GT results with patients [34]. The included studies identified considerable variation in knowledge and confidence with DTC-GT across and between HCPs, with CGs and PCPs reporting both high and low levels of knowledge and confidence in their ability to understand, interpret, and communicate results with patients surrounding DTC-GTs [21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, 32, 38]. More specifically, while one study identified that only 16% of PCPs felt that DTC-GT results were too difficult to understand [38], another study with reported that 96% of participating urologists and PCPs did not feel confident and 79% did not feel prepared to answer patients’ questions about DTC-GT [25]. One study identified that HCPs who had personal experience with DTC-GT had improved knowledge of DTC-GT and were more likely to recommend DTC-GT to patients [29].

Experience

Genetic specialists had more DTC-GT experience than other HCPs, with 58% of genetic specialists versus 17% of PCPs had experience with patients bringing them personal DTC-GT results [34]. Three studies involving GCs looked at experience with patients inquiring about DTC-GT, with 40% to 94% of GCs having encountered questions related to DTC-GT results review [26, 30, 32]. Conversely, an earlier study reported that only about one quarter of GCs had previous experience with a patient asking about DTC-GT results [32]. Overall, PCPs and other non-genetic specialists (e.g. neurologists) had fewer experiences with patients presenting with DTC-GT results, with a range of 8% to 15% of HCPs reporting experience with patients inquiring about DTC-GT results [22, 24, 25, 36]. Only 5% of PCPs had five or more patients share DTC-GT health risk results with them in the past year, while 30% had five or less patients share these results with them, and 65% did not have any [31]. For family physicians, 71% had never had patients ask them about DTC-GT, while 28% had patients ‘rarely’ ask them about DTC-GT [33]. One study mentioned healthcare providers’ own experiences with DTC-GT, showing that 16% of GCs had undergone DTC-GT themselves and 9% had experience with it on behalf of their relatives [30].

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing beliefs and opinions

Clinical utility and validity of DTC-GT

Compared to CGs, more PCPs and medical specialists believed that DTC-GT was useful in the clinical setting. Most CGs emphasised that the clinical utility and validity of genetic tests should be a fundamental condition when made available to the public. However, many CGs felt that DTC-GT results were inconsequential for their patients and that DTC companies ignored consumers’ family history [23]. Further, CGs were more reluctant to trust DTC-GT results than other HCPs [22, 34, 37].

Alternatively, the perspectives of clinical utility and validity from PCPs and non-genetic specialists is mixed. Studies identified that most PCPs and urologists agreed that DTC-GT results could assist in decision making on the initiation and frequency of prostate cancer screening (86% and 76%, respectively) [25], as well as that 40% of PCPs felt that DTC-GT results would help in managing a patient [24]. Alternatively, results from another study identified that 39% of PCPs felt that DTC-GT had no clinical utility and 20% would not change patient management based on DTC-GT results [38]. Furthermore, in one study, 67% of PCPs felt that one of the barriers to discussing DTC-GT results was its lack of current relevance in clinical decision making [21].

Direct-to-consumer access to genetic testing

CGs have been consistent with regards to restricting access to certain genetic tests outside of a clinical setting. Howard and Borry reported that 90% of CGs either somewhat disagreed or strongly disagreed that testing for disorders that were preventative or treatable should be accessible directly to the public, with similar opinions surrounding testing for conditions or traits with no or somewhat mild health consequences [2]. Another study involving GCs identified only a small percentage of GCs would find DTC-GT acceptable for testing adult-onset conditions (7%) and cancer (6%). Additionally, most GCs (96%) stated that some forms of DTC-GT are acceptable [30].

Despite ease of access and availability, most CGs felt that it was a necessity for HCPs to be involved in the health-related genetic testing process [22], that DTC genetic tests should hold up to the same quality as tests offered by the healthcare system, and that medical supervision and genetic counselling should be compulsory in some form [23]. CGs were split as to who should supervise this process as some felt that it did not have to be a medical doctor but instead could be another qualified medical professional or a nurse. CGs were also split on whether involving HCPs employed directly by DTC-GT companies would be appropriate or would create a conflict of interest [23].

Beliefs that DTC-GT had positive and negative effects on consumers

HCPs expressed beliefs about positive effects of DTC-GT on consumers, with over two-thirds of PCPs indicating that there were multiple benefits to DTC testing (e.g. motivating a healthy lifestyle, detecting adult-onset diseases earlier, and assisting patients in becoming more proactive in their own health) [29]. In another study, general practitioners (GPs) believed that the following were perceived benefits to DTC-GT (convenience, promotion of preventative medicine, confidentiality of results); however, participants tended to disagree that DTC-GT provided a useful service [37]. Finally, 39% of GCs felt that DTC-GT had value, with some of the reasons being consumer access to genetic testing, increasing genetics knowledge, and providing valuable data for research use [30].

Several studies reported various concerns that HCPs had regarding the negative effects of DTC-GTs on consumers. Compared with PCPs, GCs seemed to have more concern about the harm that DTC-GT may have on consumers, with 91% of GCs disagreeing with the statement that DTC-GT caused no harm [30]. While 58% of PCPs (family physicians) felt that DTC-GT is more likely to cause harm than to provide a benefit to patients, 10% felt that it was likely to help patients and 32% felt that it was unlikely to make any difference [33]. Additionally, CGs in Europe felt that advertising by DTC companies was misleading and ‘even manipulative’, suggesting information available on company websites was often deficient [23].

DTC-GT and healthcare professional involvement

Both genetic specialists and PCPs were uncomfortable or lacked some confidence in providing genetic counselling pertaining to DTC-GT to patients. Although 91% of GCs reporting that DTC-GTs could be improved by genetic counselling, only 31% felt that they would be comfortable in providing counselling to patients with DTC-GT results [30]. Of the GCs that had experience in encountering patients with DTC-GT, approximately 33% felt negatively about these encounters, most commonly citing that DTC-GT was not the best use of clinical time and the GCs did not know how to interpret such results [30]. Just over half of the GCs felt some degree of negativity towards DTC-GT, while only 7% felt some degree of positivity about DTC-GT [30].

GCs and PCPs felt it was their responsibility to counsel patients on the benefits and risks of genetic testing, despite difficulties and frustrations with their DTC-GT involvement [2, 27]. Similarly, 62% of GPs felt that they should be involved in the DTC-GT process even though participants in this study tended to agree that DTC-GT ‘negatively impacts the [doctor]–patient relationship’ [37]. GPs felt that the following were perceived barriers for them to provide genetic counselling (expressed in the percentage who agreed with each issue): time (81%), experience (91%) and knowledge (89%) [37].

DTC-GT in the future

Overall, a minority of PCPs (49%) felt that DTC-GT felt would be commonplace in the next 5 years [24], with 58% of New Zealand unsure if DTC-GT would be an area of growth [37]. Despite this uncertainty, another study identified that 58% of PCPs (family physicians) were interested in new technological advances like DTC-GT [28].

Downstream costs and referrals due to DTC-GT

Several studies suggest how DTC-GT leads to an increased number of referrals and increased downstream costs (e.g. disease screening) by means of more follow-up visits or investigations, confirmatory genetic testing or other unnecessary procedures. In a group of PCPs and specialist physicians who had experience with patients sharing DTC-GT results, 40% made at least one referral to a specialist, with 78% of referrals to a CG or GC [31]. Additionally, the results of one study identified that 60% of internal medicine physicians felt that DTC-GT could assist in clinical decision making and that two-thirds of these physicians felt that DTC-GT could lead to earlier or more frequent disease screening in an at-risk population [38]. Further, most GCs would order confirmatory genetic testing for a patient presenting to their clinic with an Ashkenazi Jewish founder mutation in Breast Cancer gene (BRCA)1/2, irrespective of the patient’s pedigree [26]. GPs tended to agree that DTC-GT results encouraged patients to get unnecessary procedures and genetic tests while suggesting that DTC-GT puts pressure on healthcare resources that could be used for something else [37]. GPs (81%) felt that time was an anticipated barrier for them to provide genetic counselling [37]. Similarly, PCPs in one study felt that the lack of clinical time and the lack of reimbursement were some of the barriers when discussing DTC-GT results [21].

Genetic counsellors’ views of their roles in DTC-GT

GCs gave their opinions on the following possible challenges related to providing genetic counselling for DTC results in a clinical setting (percentage who found it easy compared with neutral or difficult): 1) explaining that clinical grade genetic testing was required to confirm results (86%), 2) explaining the differences between clinical and SNP-based testing (61%) and 3) managing patient anxieties and expectations (39%) [26]. In another study, 31% of GCs felt comfortable providing counselling to patients who had undergone DTC-GT, while 26% were neutral and 42% did not agree with this statement [30].

When considering how their expertise affected patients with DTC-GT, 92% of GCs who felt that their expertise was beneficial gave the following reasons: the limitations of DTC-GT were better understood with genetic counselling (75%) and that it assisted in the clarification of the medical significance of patients’ results (57%) [30]. GCs (6%) agreed or strongly agreed that DTC-GT might threaten the genetic counselling profession, while 79% disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement [30].

Ethical issues identified by HCPs surrounding DTC-GT

Ethical concerns were identified in 24 of the 27 papers. Ten ethical issues were identified in this review, which overlap with previous HCP perceptions. Of the ten ethical issues, eight were identified in papers from the previous review. The ethical issues found in each paper are summarised in Appendix C. The ethical issues on DTC-GT identified in this review (and a summary of points relating to each issue) are included in Table 3.

The five most identified ethical issues pertaining to DTC-GT were found in at least 10 of the 27 papers identified. These were: clinical utility; clinical validity/reliability; genetic counselling/GP involvement; resource use/resulting downstream costs; misinformation/understanding DTC-GT results. The psychological effects on patients and their behaviours and/or anxieties due to DTC-GT were identified in seven of the papers, while DTC-GT companies’ financial gain/advertising were only mentioned in five of the papers. The option of limiting genetic testing to a clinical setting was mentioned in two papers. Two ethical issues were only reported once each, both in the newly identified papers: 1) DTC-GT threatening the genetic counselling profession and 2) the impact of DTC-GT on the doctor–patient relationship.

Legal issues identified by HCPs surrounding DTC-GT

Legal issues were identified in 12 of the 27 papers, and were divided into four main categories. Potential discrimination on consumers’ employment, health and/or life insurance was mentioned in seven of the 27 papers. Regulation or oversight of regulation of DTC-GT was mentioned in five papers and confidentiality/privacy of genetic information was mentioned in four papers. Lastly, HCPs’ medical and legal responsibilities were mentioned in two of the new papers identified in the updated search. The legal issues found in each paper are summarised in Appendix B. The four legal issues on DTC-GT identified in the included papers (with some explanation for each issue) are included in Table 4.

Discussion

This systematic review assessed the views and knowledge of HCPs on DTC-GT while exploring the ethical and legal issues surrounding DTC-GT from the perspective of HCPs. Overall, there were more studies conducted in North America than any other region. There were also less studies of genetic specialists than of other HCPs. Furthermore, there were no studies in Europe that evaluated the views and knowledge of GCs and PCPs about DTC-GT. The extent to which tests are readily available in each country may affect the perceptions of HCPs towards DTC-GT. This highlights the need for further research in other countries (and multi-country studies) and among all types of HCPs. Although not the focus of this review, other HCPs such as pharmacists may play an important role in DTC-GT focused on pharmacogenetics [39].

As with the review conducted by Goldsmith et al., the included studies in this review revealed differences in the level of knowledge, awareness, and experiences amongst HCPs on DTC-GT. Generally, CGs and GCs seemed to fare better in all areas, potentially due to their expertise in genetics [37]. The knowledge of HCPs did not appear to increase since the previous review, suggesting that medical education and other experience related to DTC-GT has not assisted HCPs in gaining knowledge of these tests. Medical training has the potential to increase knowledge of DTC-GT [4] and practicing HCPs can gain further knowledge about DTC-GT and genetics by accessing web-based resources created by genetic specialists [7, 28]. Alternatively, one study in this review suggested that HCPs’ knowledge on DTC-GT information and interpretation could improve by personally undergoing DTC-GT [29].

After nearly a decade since the previous review, studies still show high levels of reluctance amongst HCPs to provide genetic counselling and information about DTC-GT to patients. The lack of confidence in this area is potentially tied to findings showing that many HCPs still lack sufficient knowledge about DTC-GT. Furthermore, HCPs (specifically, PCPs) continue to have low levels of experience with patients that have DTC-GT concerns. However, the studies in this review have shown that there is a slow increase in these experiences, particularly amongst GCs and CGs. Interestingly, GCs seem to have more experience in DTC-GT than CGs. However, experiences for CGs seemed to increase over time even though these experiences were not common practice [2, 22]. Further, CGs have been consistent with regards to their opinions about restricting access to certain DTC tests [2, 23].

Ethical aspects in direct-to-consumer genetic testing from the perspective of HCPs

From the results of this review, there were several ethical components of DTC-GT that HCPs identified. Several studies in this review reported that HCPs agreed that genetic counselling was an important and useful component of genetic testing, and should be provided to consumers purchasing DTC-GT to provide consumers with additional information to understand the benefits, risks, and limitations of genetic testing [40]. Further, HCPs were concerned that genetic counselling through DTC-GT companies may be inadequate or non-existent [27, 40, 41]. Additional studies showed that HCPs felt that DTC-GT would be more acceptable to them if genetic counselling was provided [42] and that HCPs believed that DTC-GT [29] should be restricted to a clinical setting, with HCPs involved in providing genetic counselling and/or genetic testing.

Compared to other HCPs [4], genetic specialists were more concerned and more aware of the potential harm of DTC-GT to consumers. Additionally, there was ongoing concern about the clinical utility and validity of DTC-GT, potentially due to the lack of scientific evidence to support clinical value and accuracy of these tests [4]. Several studies in this review identified that HCPs had mixed opinions on the clinical value and utility of DTC-GT results, with genetic specialists more likely to be sceptical of the clinical utility of DTC-GT [43].

Studies in this review identified that HCPs were concerned about the accuracy and reliability (i.e. the clinical validity) of DTC-GT results. Research by Tandy-Connor et al. [43] revealed that DTC-GT results that showed a positive result for a pathological gene variant had a false positive rate of 40% after performing accredited confirmatory testing, contributing to the basis of these concerns.

Autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice

Autonomy refers to an individual’s freedom from external constraint and the presence of critical mental capacities such as understanding, intending and voluntary decision-making capacity [13]. This principle can be applied to concepts such as informed consent, the understanding of information by consumers and the avoidance of coercion of these consumers when using DTC-GT services. This systematic review identified that HCPs were concerned that consumers were being misinformed, misled, and may not understand what they are undertaking when they purchase DTC-GT services [22, 37, 42, 44]. This review also identified that HCPs believed that advertising by DTC-GT companies contributed to misinformation, subsequently confusing and misleading consumers [22, 38, 45]. When genetic testing is provided in a traditional healthcare setting, HCPs are obligated to obtain informed consent from the patient who will undergo testing. Informed consent can only be valid if the patient has full capacity to consent, voluntarily consents, and most importantly, has been given adequate information in an understandable way about the benefits and risks and function and type of test that will be done [46]. Since DTC-GT often does not involve HCPs, informed consent is unlikely to occur. Companies who provide these services are more likely to have a contractual agreement with the consumer, by means of a ‘terms of service’ agreement or a ‘terms and conditions’ prerequisite for obtaining their services [47, 48]. Companies often state that the consumer has come into this agreement by viewing their website or by purchasing a service [47]. While considered a legal contract, these agreements arguably do not meet the definition of consent, which then stands to reason that agreements between patients and DTC-GT companies are not the same as the informed consent obtained in healthcare settings [47]. Moreover, DTC-GT companies operating as commercial entities do not claim to be medical providers; and therefore, do not have an obligation or ‘duty of care’ towards the consumer or a ‘code of ethics’ they need to follow [48].

The act of doing something that benefits others is known as beneficence, an important principle in healthcare ethics, while non-maleficence is the principle of causing no ‘harm’ to others [13]. This systematic review identified several perceived positive aspects to DTC-GT which may benefit consumers, or minimally, not cause harm. First, access to DTC-GT could increase consumers’ genetics knowledge and increase awareness to disease predisposition [3, 30, 49]. Additionally, consumers are encouraged to be more proactive in their healthcare choices [3, 29], and can be motivated to lead a healthier lifestyle [29, 38]. Despite any benefits, HCPs noted that DTC-GT results need to be confirmed by clinical genetic testing that is reliable and validated [26, 38], and genetic test results received from DTC-GT services should not be used to inform patient or clinical healthcare decisions [6, 47]. Conversely, studies in this review showed that HCPs believe that DTC-GT could cause harm to consumers. Receiving a test result showing that the patient has a pathogenic variant of the BRCA1/2 gene, for example, has the potential to cause distress and harm. First, a consumer is unlikely to have received any pre-test genetic counselling to prepare them and to help them understand the implications of such a result. This supports claims made by HCPs regarding the importance of genetic counselling before getting DTC-GT [2, 22, 30]. Another concern is DTC-GT companies using complicated terminology and long disclaimers on their websites may mislead and result in misinterpretation of DTC-GT results [47]. Studies in this review found that HCPs believed that this was one of the many issues of DTC-GT for consumers [22, 37, 38, 42, 45].

Justice is framed by legal, moral and cultural principles [13]. The application of this principle assists in the discussion of what should be considered due, fair, or owed within a bioethical dilemma [13] and includes aspects such as fairness and equality in the use of healthcare resources and HCPs’ time. Some HCPs believed that they might feel obligated to refer patients to specialists or recommend additional screening procedures based on DTC-GT results [38, 45], which may be difficult for populations to access due to costs and other access-related barriers. Further, HCPs reported that access to genetic counselling may be limited due to lack of time and resources, with some HCPs reporting that DTC-GT consultations were not a good use of clinical time [21, 22, 37].

Legal aspects in direct-to-consumer genetic testing

In addition to DTC-GT ethical concerns, there were several legal concerns from the perspective of HCPs that were identified in this review. HCPs had concerns that DTC-GT results would have negative implications for consumers, with concerns that these results could lead to employment discrimination [25, 38, 44, 45] or discrimination when applying for life or health insurance [24, 25, 27, 38, 44, 45]. Some of the studies reporting such concerns were conducted in countries that have legal protection in place to prevent genetic discrimination, suggesting that HCPs were not aware of genetic discrimination laws [4, 36]. For example, the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA) in the US gives a person federal protection from health and employment discrimination [36]. However, the GINA does not protect citizens against discrimination when applying for life or disability insurance [36]. Furthermore, Article 11 of the Council of Europe’s ‘Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine’ states that discrimination based on a person’s ‘genetic heritage’ is prohibited [18]. In addition, HCPs in some of the review studies expressed this as a concern [22, 35, 37].

Some also believed that advertising of DTC-GT services should be regulated in the same way that DTC medication is regulated [37]. Many DTC-GT companies put disclaimers on their websites to inform consumers that the tests that they provide are not medical tests and that they are not ‘fit for purpose’ [47], however, this is contrary to EU regulation [16], which states that DTC genetic tests are ‘in vitro diagnostic medical devices’ and need to be fit for purpose. If this is the case, it suggests that these services should not be governed under medical regulations but rather contractual laws since they are commercial entities [47]. However, many of the terms of service or agreements that consumers sign when purchasing DTC-GT falls short from a consumer protection point of view [47]. In general, there is a lack of adequate regulation of DTC-GT [3, 4, 50].

Strengths and limitations

Limitations include that many of the included studies reported on perceived opinions and knowledge by using hypothetical scenarios, rather than looking at real-life experiences of the participants. However, this may be explained by low rates of DTC-GT experience amongst many HCPs, especially those that do not specialise in genetics. Most survey-based studies had poor response rates and qualitative studies rarely reported reaching their target sample size. Strengths of this review are a wide search strategy, mirroring the previous review on this topic. Although only 20% of data extraction was checked by a second author (FM), the narrative nature of the extracted data minimised the risk of errors. This review focused only on health-related genetic testing, and therefore other aspects of DTC-GT (e.g. pharmacogenetics) could be explored further. Further research could focus solely on DTC pharmacogenetic testing as it gains prominence, given the implications, ethical issues and legal issues are potentially different to DTC-GT for disease susceptibility.

Conclusions

In addition to themes identified in previous reviews of DTC-GT, there are multiple ethical and legal concerns to consider in DTC-GT, as identified by HCPs. This review highlights important issues of relevance to policymakers, as well as for HCPs so that they can effectively address their patients’ questions and to interpret their DTC-GT results. Regulations on DTC-GT should be improved since numerous countries have inadequate or no laws regulating this type of testing [3]. However, some regulations on DTC-GT have been implemented in Europe. HCP concerns suggest a need for tighter controls on the advertising of DTC-GT by companies, the information provided to consumers, and how consumer data is used and shared [48]. Genetic counselling should be readily available and emphasised to consumers purchasing DTC-GT [42]. Education of HCPs on clinical genetics also needs to be addressed, especially amongst PCPs who are increasingly likely to assist patients that have DTC-GT questions or results. It is likely with the restriction of in-person consultations and shift to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, this may have provided an additional impetus for people to consider using DTC-GT. If an increase in use of DTC-GT is seen following the onset of the pandemic, even greater consideration will be needed of how HCPs can provide appropriate care in this context. Overall, there are several opportunities to improve the appropriate use and interpretation of DTC-GT through provider/patient education and support, and this may also help to address HCP concerns surrounding legal and ethical issues of DTC-GT.

References

Levitt DM. Let the consumer decide? The regulation of commercial genetic testing. J Med Ethics. 2001;27:398–403.

Howard HC, Borry P. Survey of European clinical geneticists on awareness, experiences and attitudes towards direct-to-consumer genetic testing. Genome Med. 2013;5:45.

Dandara C, Greenberg J, Lambie L, Lombard Z, Naicker T, Ramesar R, et al. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: To test or not to test, that is the question. S Afr Med J. 2013;103:510–2.

Covolo L, Rubinelli S, Ceretti E, Gelatti U. Internet-based direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e279.

Howard HC, Borry P. To ban or not to ban? Clinical geneticists’ views on the regulation of direct‐to‐consumer genetic testing. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:791–4.

23andMe—Compare our DNA Tests. 23andMe. 2021. https://www.23andme.com/en-eu/compare-dna-tests/.

Goldsmith L, Jackson L, O’Connor A, Skirton H. Direct-to-consumer genomic testing from the perspective of the health professional: a systematic review of the literature. J Community Genet. 2013;4:169–80.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1435–43.

Dobrescu AI, Nussbaumer SB, Klerings I, Wagner G, Persad E, Sommer I, et al. Restricting evidence syntheses of interventions to English-language publications is a viable methodological shortcut for most medical topics: a systematic review: Excluding English-language publications a valid shortcut. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;137:209–17.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ Br Med J. 2015;349:g7647.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. 2021. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

Beauchamp TL. The ‘four principles’ approach to health care ethics. In: Ashcroft RE, editor. Principles of Health Care Ethics. 2nd edn. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 2007.

Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics. 5th edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Guide to Professional Conduct and Ethics for Regiistered Mediical Practitioners (Amended), 2019. https://msurgery.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Guide-to-Professional-Conduct-and-Ethics-8th-Edition-2016-.pdf.

Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repealing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision 2010/227/EU. OJEU L 117. 2017;60:176–332. 2017. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R0746.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008. 2008. https://www.eeoc.gov/statutes/genetic-information-nondiscrimination-act-2008.

ETS 164—Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, 4.IV.1997. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/168007cf98.

(FDA) FDA. Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Tests. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/in-vitro-diagnostics/direct-consumer-tests.

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA relevance). 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/reports/kd0419345enn.pdf.

Chambers CV, Axell-House DB, Mills G, Bittner-Fagan H, Rosenthal MP, Johnson M, et al. Primary care physicians’ experience and confidence with genetic testing and perceived barriers to genomic medicine. J Fam Med. 2015;2:1024.

Kalokairinou L, Borry P, Howard HC. Attitudes and experiences of European clinical geneticists towards direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a qualitative interview study. N Genet Soc. 2019;38:410–29.

Kalokairinou L, Borry P, Howard HC. ‘It’s much more grey than black and white’: clinical geneticists’ views on the oversight of consumer genomics in Europe. Per Med. 2020;17:129–40.

Bernhardt BA, Zayac C, Gordon ES, Wawak L, Pyeritz RE, Gollust SE. Incorporating direct-to-consumer genomic information into patient care: attitudes and experiences of primary care physicians. Per Med. 2012;9:683–92.

Birmingham WC, Agarwal N, Kohlmann W, Aspinwall LG, Wang M, Bishoff J, et al. Patient and provider attitudes toward genomic testing for prostate cancer susceptibility: a mixed method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:279.

Burke S, Mork M, Qualmann K, Woodson A, Jin Ha M, Arun B, et al. Genetic counselor approaches to BRCA1/2 direct-to-consumer genetic testing results. J Genet Couns. 2021;30:803–12.

Carroll JC, Makuwaza T, Manca DP, Sopcak N, Permaul JA, O’Brien MA, et al. Primary care providers’ experiences with and perceptions of personalized genomic medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:e626–35.

Carroll JC, Allanson J, Morrison S, Miller FA, Wilson BJ, Permaul JA, et al. Informing integration of genomic medicine into primary care: an assessment of current practice, attitudes, and desired resources. Front Genet. 2019;10:1189.

Haga SB, Kim E, Myers RA, Ginsburg GS. Primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience with personal genetic testing. J Pers Med. 2019;9:29.

Hsieh V, Braid T, Gordon E, Hercher L. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies tell their customers to ‘see a genetic counselor’. How do genetic counselors feel about direct-to-consumer genetic testing? J Genet Couns. 2021;30:191–7.

Jonas MC, Suwannarat P, Burnett-Hartman A, Carroll N, Turner M, Janes K, et al. Physician experience with direct-to-consumer genetic testing in Kaiser permanente. J Pers Med. 2019;9:47.

Leighton JW, Valverde K, Bernhardt BA. The general public’s understanding and perception of direct-to-consumer genetic test results. Public Health Genom. 2012;15:11–21.

Mainous AG 3rd, Johnson SP, Chirina S, Baker R. Academic family physicians’ perception of genetic testing and integration into practice: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2013;45:257–62.

McGrath SP, Walton N, Williams MS, Kim KK, Bastola K. Are providers prepared for genomic medicine: interpretation of Direct-to-Consumer genetic testing (DTC-GT) results and genetic self-efficacy by medical professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:844.

Unim B, De Vito C, Hagan J, Villari P, Knoppers BM, Zawati M. The provision of genetic testing and related services in Quebec, Canada. Front Genet. 2020;11:127.

Salm M, Abbate K, Appelbaum P, Ottman R, Chung W, Marder K, et al. Use of genetic tests among neurologists and psychiatrists: knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and needs for training. J Genet Couns. 2014;23:156–63.

Ram S, Russell B, Gubb M, Taylor R, Butler C, Khan I, et al. General practitioner attitudes to direct-to-consumer genetic testing in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2012;125:14–26.

Kittikoon S, Pithukpakorn M, Pramyothin P. Physician awareness, preparedness, and opinions toward consumer-initiated genetic testing in Thailand: views from a changing landscape. J Genet Counsel. 2021;30:1535–43.

Gammal RS, Smith DM, Wiisanen KW, Cusimano JM, Pettit RS, Stephens JW, et al. The pharmacist’s responsibility to ensure appropriate use of direct-to-consumer genetic testing. JACCP J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021;4:652–8.

Brett GR, Metcalfe SA, Amor DJ, Halliday JL. An exploration of genetic health professionals’ experience with direct-to-consumer genetic testing in their clinical practice. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:825–30.

National Doctors Training and Planning: Review of the Clinical Genetics Medical Workforce in Ireland. HSE; 2019. https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/leadership-education-development/met/plan/specialty-specific-reviews/clinical-genetics-2019.pdf.

Hock KT, Christensen KD, Yashar BM, Roberts JS, Gollust SE, Uhlmann WR. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: an assessment of genetic counselors’ knowledge and beliefs. Genet Med. 2011;13:325–32.

Tandy-Connor S, Guiltinan J, Krempely K, LaDuca H, Reineke P, Gutierrez S, et al. False-positive results released by direct-to-consumer genetic tests highlight the importance of clinical confirmation testing for appropriate patient care. Genet Med. 2018;20:1515–21.

Ohata T, Tsuchiya A, Watanabe M, Sumida T, Takada F. Physicians’ opinion for ‘new’ genetic testing in Japan. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:203–8.

Powell KP, Cogswell WA, Christianson CA, Dave G, Verma A, Eubanks S, et al. Primary care physicians’ awareness, experience and opinions of direct-to-consumer genetic testing. J Genet Couns. 2012;21:113–26.

National Consent Policy. HSE: Quality & Patient Safety Division; 2013. https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/immunisation/hcpinfo/conference/waterford9.pdf.

Phillips AM. Reading the fine print when buying your genetic self online: direct-to-consumer genetic testing terms and conditions. N. Genet Soc. 2017;36:273–95.

Bunnik EM, Janssens ACJW, Schermer MHN. Informed consent in direct-to-consumer personal genome testing: the outline of a model between specific and generic consent. Bioethics. 2014;28:343–51.

Explore 23andMe’s scientific discoveries. 23andMe. 2021. https://www.23andme.com/publications/.

Rafiq M, Ianuale C, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a systematic review of european guidelines, recommendations, and position statements. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2015;19:535–47.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank William Frank Randall for reviewing and making suggestions on an earlier report of this study.

Funding

No specific funding was provided to support this work. LTM is funded by the Health Research Board (grant no. ILP-HSR-2019-006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM conceived the study, MM and FM designed the study, MM and LT screened records, MM extracted data and FM verified data, MM, LTM and FM analysed the data, MM drafted the paper and all authors provided critical revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Martins, M.F., Murry, L.T., Telford, L. et al. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: an updated systematic review of healthcare professionals’ knowledge and views, and ethical and legal concerns. Eur J Hum Genet 30, 1331–1343 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01205-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01205-8

This article is cited by

-

Cascade genetic testing for hereditary cancer syndromes: a review of barriers and breakthroughs

Familial Cancer (2024)

-

2022: the year that was in the European Journal of Human Genetics

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing: A Comprehensive Review

Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science (2023)

-

The utility of population level genomic research

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)