Abstract

Background

Food subsidies for healthier foods and higher taxes for less healthy alternatives have been increasingly used to promote a healthy diet. Yet, some have argued that the fiscal burden on unhealthy products would fall disproportionately on the worse-off, raising equity concerns. This study estimates the association between income and the consumption of key food groups linked to the Mediterranean diet in the adult Portuguese population.

Methods

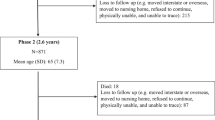

We used data from the Portuguese National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF 2015–2016), which observed the daily diet of individuals aged above 18 and below 79 years old (n = 3242). Logistic regression models were used to estimate the magnitude of the association between self-reported household income categories and consumption of foods related to the Mediterranean diet (fish, vegetables, fruits and legumes), and not (sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, cakes & pastries and processed meats). Stratified analyses were performed by education and age categories.

Results

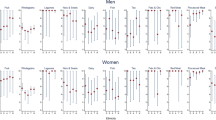

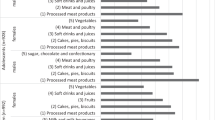

We observed that the intake of fish (35.8 vs 38.8 g p = 0.02), vegetables (146.7 vs 166.2 g p < 0.01), and fruits (119.8 vs 150.1 g p < 0.01) was positively related to income, with a clear gradient for the two latter. Yet, the positive income-consumption link for fish was only observed among low-educated people, and the one for legumes among high educated and youths. Conversely, the consumption of most non-Mediterranean foods was not positively related to income categories, with the exception of sweets (34.8 vs 31.8 g p = 0.01) and cakes (26.4 vs 21.4 g p < 0.01) (more prevalent among the better-off).

Conclusions

The consumption of healthy food is mostly consistently related to income, contrary to the intake of unhealthy ones. It may well be, therefore, that subsidies to healthy foods could allow access to the worse-off while taxing unhealthy food will not impose a disproportionate burden on them.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Cancer Research Fund. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: World Cancer Research Fund. American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Lampousi A-M, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, et al. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;(C):ajcn153148.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Lampousi A-M, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, Schwedhelm C. et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:1462–73.

Hunter DJ, Reddy KS. Noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1336–43.

Ezzati M, Riboli E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:954–64.

Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Méjean C. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé‚ prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018;k322:360

Niebylski ML, Redburn KA, Duhaney T, Campbell NR. Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition. 2015;31:787–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2014.12.010.

Wilde P, Huang Y, Sy S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Jardim TV, Paarlberg R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a US national sugar-sweetened beverage tax with a multistakeholder approach: who pays and who benefits. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:276–84.

Cobiac LJ, Tam K, Veerman L, Blakely T. Taxes and subsidies for improving diet and population health in Australia: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. PLoS Med. 2017;14:1–18.

World Health Organization. Fiscal policies for diet and the prevention of noncommunicable diseases. WHO Regional Office for Europe. Geneva; http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/fiscal-policies-diet-prevention/en/. 2015.

Sánchez-Romero LM, Penko J, Coxson PG, Fernández A, Mason A, Moran AE, et al. Projected impact of Mexico’s sugar-sweetened beverage tax policy on diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a modeling study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:1–17.

Monsivais P, Drewnowski A. The rising cost of low-energy-density foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:2071–6.

Drewnowski A. Obesity and the food environment: dietary energy density and diet costs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3 Suppl):154–62.

Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:643–60.

Tong TYN, Imamura F, Monsivais P, Brage S, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, et al. Dietary cost associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and its variation by socio-economic factors in the UK Fenland Study. Br J Nutr. 2018;119:685–94.

Jones NRV, Conklin AI, Suhrcke M, Monsivais P. The growing price gap between more and less healthy foods: analysis of a novel longitudinal UK dataset. PLoS ONE. 2014;e109343:9

Rajagopal S, Barnhill A, Sharfstein JM. The evidence—and acceptability—of taxes on unhealthy foods. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2018;7:7–9.

Thow AM, Downs SM, Mayes C, Trevena H, Waqanivalu T, Cawley J. Fiscal policy to improve diets and prevent noncommunicable diseases: from recommendations to action. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:201–10. http://www.who.int/entity/bulletin/volumes/96/3/17-195982.pdf

Goiana-da-silva F, Nunes AM, Miraldo M, Bento A, Breda J, Araújo FF. Using pricing policies to promote public health: the sugar sweetened beverages taxation experience in Portugal Fiscalidade ao Serviço da Saúde Pública: A Experiência na Tributação das Bebidas Açucaradas em Portugal. Acta Medica Portuguesa. 2018;31:1–5.

Pauly M, Mcguire T, Barros P. Handbook of health economics. 2011;2:1126. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444535924000177.

Carter SM, Rychetnik L, Dietetics PG, Lloyd B, Kerridge IH, Baur L, et al. Evidence, ethics, and values: a framework for health promotion. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:465–72.

Mackenbach JD, Brage S, Forouhi NG, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Does the importance of dietary costs for fruit and vegetable intake vary by socioeconomic position? Br J Nutr. 2015;114:1464–70.

Inglis V, Ball K, Crawford D. Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration. Appetite 2005;45:334–43.

Owens J, Cribb A. Beyond choice and individualism: understanding autonomy for public health ethics. Public Health Ethics. 2013;6:262–71.

Azétsop J, Joy TR. Access to nutritious food, socioeconomic individualism and public health ethics in the USA: a common good approach. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2013;8:16.

Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344–a1344.

Sofi F. The Mediterranean diet revisited: evidence of its effectiveness grows. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2009;24:442–6.

Direção-Geral de Saúde. Programa Nacional para a Promoção da Alimentação Saudável. Lisboa: Direção-Geral de Saúde; 2015.

Lopes C, Torres D, Oliveira A, Severo M, Guiomar S, Alarcao V. et al. The IAN-AF Consortium. National Food, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Survey of the Portuguese General Population (2015–2016). 2018;e42:20

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Estatísticas de Portugal. Recenseamento da População e Habitação—Census. https://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=censos2011_apresentacao&xpid=CENSOS. 2011.

Lopes C, Torres D, Oliveira A, Severo M, Guiomar S, Alarcão V, et al. National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey of the Portuguese general population. EFSA Support Publ. 2017;14:37.

Faria N, Sousa N, Soares R, Guiomar S, Lobato L, Oliveira C, et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física, IAN-AF 2015-2016: Manual Fotográfico de Quantificação de Alimentos. Universidade do Porto. www.ian-af.up.pt. 2017.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The food classification and description system FoodEx 2 (revision 2). EFSA Support Publ. Parma, Italy: European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); 2017. 12.

De Boer EJ, Slimani N, Van’t Veer P, Boeing H, Feinberg M, Leclercq C. et al. Rationale and methods of the European Food Consumption Validation (EFCOVAL) Project. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:1–4. www.nature.com/ejcn.

Fidanza F, Alberti A, Lanti M, Menotti A. Mediterranean Adequacy Index: Correlation with 25-year mortality from coronary heart disease in the Seven Countries Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;14:254–8.

Lopes C, Torres D, Oliveira A, Severo M, Alarcão V, Guiomar S, et al. National Food, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Survey of the Portuguese General Population 2015–2016: summary of results. p. 1–122. www.ian-af.up.pt. 2018.

Garner TI, Ruiz-Castillo J, Sastre M. The influence of demographics and household-specific price indices on consumption-based inequality and welfare: a comparison of Spain and the United States. South. South Econ J. 2003;70:22.

Rojas M. Household equivalence scale. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. 141. Dordrecht: Springer; 1989. p. 1077–9.

Parker R, Fenwick R. The Pareto curve and its utility for open-ended income distributions in survey research. Social Forces. 1983;61:872–85.

McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:29–48.

Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1107–17.

James WP, Nelson M, Ralph A, Leather S. Socioeconomic determinants of health. The contribution of nutrition to inequalities in health. BMJ 1997;314:1545–9.

Correia D, Severo M, Lopes C. The role of socio-economic factors in food consumption of Portuguese children and adolescents: Results from the National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2015–2016. Br J Nutr. 2020;124:591–601.

Bonaccio M, Bonanni AE, Di Castelnuovo A, De Lucia F, Donati MB, De Gaetano G, et al. Low income is associated with poor adherence to a Mediterranean diet and a higher prevalence of obesity: Cross-sectional results from the Moli-sani study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:1–10.

Bonaccio M, Bes-Rastrollo M, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L. Challenges to the Mediterranean diet at a time of economic crisis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26:1057–63.

Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Bonanni A, Costanzo S, De Lucia F, Persichillo M, et al. Decline of the Mediterranean diet at a time of economic crisis. Results from the Moli-sani study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:853–60.

Chatzivagia E, Pepa A, Vlassopoulos A, Kapsokefalou M, Malisova O, Filippou K. Nutrition transition in the post-economic crisis of Greece: assessing the nutritional gap of food-insecure individuals. A cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2019;11:2914

Alves R, Perelman J. Dietary changes during the Great Recession in Portugal: comparing the 2005/2006 and the 2014 health surveys. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22:1–8.

Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Rendimento e condições de vida 2016: 2,6 milhões de residentes em risco de pobreza ou exclusão social em 2016. Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística; 2017. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=281091354&DESTAQUESmodo=2.

Rao M, Afshin A, Singh G, Mozaffarian D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e004277

Lagström H, Halonen JI, Kawachi I, Stenholm S, Pentti J, Suominen S. et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and adherence to dietary recommendations among Finnish adults: a retrospective follow-up study. Health Place. 2019;55:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.10.007.

Hebert JR, Clemon L, Pbert L, Ocknene IS, Ockene JK. Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:389–98.

Funding

The study received funding from SILNE-R - European Commission - Horizon 2020 (Grant 635056).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alves, R., Lopes, C. & Perelman, J. Healthy eating: a privilege for the better-off?. Eur J Clin Nutr 76, 134–142 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-021-00926-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-021-00926-1

This article is cited by

-

Front-of-pack nutrition labels: an equitable public health intervention

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2023)