Abstract

Although there have been continuous improvements in child oral health over recent decades, first permanent molars (FPMs) remain susceptible to early caries and can often be affected by hypomineralisation. We highlight current thinking in caries management and the restoration of hypomineralised FPMs, while also discussing enforced loss of these teeth within the context of interceptive extractions or extractions as part of orthodontic treatment. Compromised FPMs can negatively impact on quality of life for a child and present significant management challenges for the dental team. Although a high-quality evidence base is lacking for the different treatment options, early diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment planning are key to achieving the best outcomes.

Key points

-

Compromised first permanent molars continue to be a common clinical finding among children in the UK.

-

Treatment planning should involve a team approach and rely upon careful assimilation of social, behavioural, medical and dental factors, alongside relevant preferences of the child and their family.

-

Caries management and the restoration of hypomineralised first permanent molars is discussed, along with the consequences of enforced extraction of these teeth for the underlying occlusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental care for any child, especially those with high caries risk, should be founded on personalised and evidence-based prevention, aimed at averting disease and a host of potential negative impacts for the child, their family and service providers. A sizeable body of evidence supports the effectiveness of various professionally applied and home-care preventive regimens to help reduce caries and improve oral health outcomes for children.1,2

Given this preventive-based ethos, one may ask why dental health professionals are still seeing so many children with compromised first permanent molars (FPMs) in their daily practice. Moreover, how should these children be managed, given the complexity of decision-making in relation to long-term prognosis, orthodontic status, and relevant child/parental factors? Here, we provide a pragmatic commentary on the broad principles of dental care for children with FPMs of poor prognosis.

Why are we still seeing children with compromised FPMs?

General dental practitioners (GDPs) in the UK have recently reported that around 10% of the children that they see will have compromised FPMs.3 Data from the Office of National Statistics (2015) corroborate this clinical impression, with the finding that 5% of eight-year-olds, and an alarming 25% of 15-year-olds, have some form of caries in their FPMs.4 It is also important to recognise that carious FPMs may have an underlying enamel defect, which can predispose them to a greater risk of caries. Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) is an increasingly common systemic condition, characterised by qualitative enamel defects predominating in the FPMs and incisor teeth.5 Not only are affected molars more likely to develop caries (reportedly up to six times), but they are also prone to rapid and extensive post-eruptive enamel breakdown, which can cause extreme dentine hypersensitivity.5,6 Epidemiological data suggest that MIH affects around 13% of children worldwide, so even in communities with decreasing caries rates, clinicians will continue to face the challenge of managing children with poor prognosis FPMs.7

Clinical management of children with one or more compromised FPMs

Treatment planning for children with carious and/or hypomineralised FPMs relies on the assimilation of social, behavioural, medical and dental factors, alongside child and family preferences. The European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry has recently published Best clinical practice guidance, specific to children with MIH, which provides a consensus for treatment alongside the quality of the supporting evidence for each option.8 It is interesting to reflect on reported differences in management approaches between various clinician groups and between different countries.3 Notwithstanding these acknowledged disparities, an early diagnosis of enamel hypomineralisation and/or caries is paramount to inform pre-emptive (simple) treatment and maximising best clinical and patient-reported outcomes over the longer-term.

The initial assessment

It is important to carry out a comprehensive and timely history and examination for any child with FPMs of concern. As will be discussed later, the stage of dental development is an important factor when planning the timing of any extractions. Furthermore, clinicians should be aware of the potential for congenitally missing second premolars in children with MIH which would represent a contraindication to FPM extraction.9 Table 1 highlights some of the factors that should be elicited and taken into consideration for all children with compromised FPMs.

Caries prevention and management of dentine hypersensitivity

Having addressed any acute presenting complaint, the first phase of any treatment plan is to establish a preventive programme.2 Children with carious and/or hypomineralised FPMs require optimal topical fluoride regimens, including professionally applied fluoride varnish at least twice a year, 2800 ppm fluoride toothpaste (if older than ten years old), and, ideally, a daily fluoridated mouthwash, in conjunction with dietary advice and toothbrushing instruction. Fissure sealants should be applied on any permanent molars not requiring restoration or extraction, although bonding to hypomineralised enamel can be unpredictable.10 This, together with poor moisture control (stemming from an underlying dentine hypersensitivity and/or child anxiety) can lead to higher failure rates of conventional resin-based fissure sealants.8 An alternative and less technique-sensitive approach for both child and clinician is the interim use of a resin-modified glass ionomer sealant restoration (Fig. 1).8 Although some clinicians advocate the use of remineralising products (casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate products), desensitising toothpastes, or silver fluoride preparations for the management of MIH hypersensitivity, the evidence base has not been established.10 Having carried out an initial clinical and radiographic assessment (ideally soon after eruption of the FPMs) the initial phase of treatment aims to manage any symptoms or anxiety, establish a personalised preventive strategy, and protect the teeth from any further post-eruptive breakdown, caries or erosion. The next consideration is to evaluate the likely long-term prognosis and treatment need for each FPM, alongside the variables outlined in Table 1. However, a definitive decision may not be appropriate at the first assessment, so the child should be kept under regular review and the family made aware that there are several future treatment options.

Taking a restorative approach

Current thinking regarding dentine or cavitated caries management is orientated towards minimally invasive approaches, which favour selective or stepwise caries removal, rather than complete.11 However, in the case of deep caries in asymptomatic vital FPMs, partial or coronal pulpotomies (using materials such as mineral trioxide aggregate or biodentine) have been reported to have variable success rates of around 60-80% at five years.12,13 Crucial to the success of these techniques is optimal moisture control with rubber dam and the use of restorative materials that provide an hermetic seal. The use of amalgam is no longer supported for children under the age of 15 in the UK.14 It is not common practice to embark on a pulpectomy for FPMs for this young age group in the UK and while endodontic treatment is possible (and sometimes indicated), extraction of these teeth (with or without orthodontic space closure) is likely to achieve better patient and cost outcomes in the longer-term.15

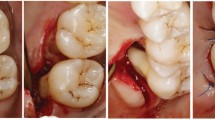

More challenging than simple caries management is the restoration of hypomineralised FPMs. A recent systematic review provides a comprehensive critique of the various restorative options for children with MIH.10 For mildly affected FPMs (minimal post-eruptive breakdown), a composite resin restoration, extending beyond the visibly affected enamel opacity, would seem to be the best option. In cases where the opacities involve multiple surfaces, together with rapid post-eruptive breakdown and hypersensitivity, direct or indirect composite resin restorations may be considered. Expert opinion seems to support the removal of any soft hypomineralised enamel before the placement of an indirect restoration with optimal rubber dam moisture control.10 For some children with severe MIH, full coronal coverage using a preformed metal crown (PMC) may offer a simple medium-term restoration. In such cases, the non-invasive Hall technique for PMC placement usually obviates the need for local anaesthetic and tooth tissue removal; beneficial for young and/or anxious children. A PMC is not considered a definitive restoration (due to potential wear and periodontal damage), but it can be advantageous in situations where the FPM needs to be retained for several years until the optimal time for its planned removal (Fig. 2).

A nine-year-old child with upper anterior crowding, hypomineralised second primary molars and FPMs. Preformed metal crowns were placed (using the non-invasive Hall technique) as a mid-term restoration until the eruption of the second permanent molars and planned orthodontic extraction of the compromised FPMs

Any restorative intervention for a young child with compromised FPMs will confer a long-term treatment burden for that patient. Indeed, between the age of 9-18-years old, children with MIH can undergo four times as many treatment episodes (usually retreatment of failed restorations) for these teeth compared to a control group.16 By the age of 18 years, the MIH group continued to face an ongoing cycle of restorative interventions.

Indications for extraction

The removal of one or more compromised FPMs is not common practice outside the UK, and a restorative approach is generally favoured in Europe.8 This may be partly explained by the higher caries prevalence in the UK and more widespread societal acceptance of extractions under sedation or general anaesthetic. Nonetheless, it is argued that extractions may offer the most appropriate treatment for some children with extensive caries and/or hypomineralisation, particularly those experiencing symptoms.17 The rationale for FPM 'interceptive' extraction is that it obviates the need for ongoing restorative and endodontic care, and encourages second permanent molar eruption with space closure between this tooth and the second premolar, particularly if undertaken at the 'ideal' stage of dental development (that is, around the age of 8-10 years, with the second permanent molar still developing within alveolar bone). Variable success rates have been reported in the maxillary and mandibular arches, with most researchers citing an 80-90% chance of contact in the maxillary arch and around 50-60% in the mandible.18,19,20 However, the evidence base for clinical and patient-based outcomes associated with FPMs remains surprisingly sparse, with a lack of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) (Box 1). In general, there are some acknowledged clinical and patient-related factors which tend to favour the extraction of one or more compromised FPMs (Table 2).

Orthodontic considerations

The role of the orthodontist in managing poor prognosis FPMs is to liaise with the paediatric dentist or GDP, and give advice within the context of any potential interceptive extractions and overall management of any underlying malocclusion. It is important to state that the key to orthodontic decision-making is clear direction on the long-term prognosis of each affected tooth and this should come from the paediatric dentist or GDP, particularly in relation to teeth affected by MIH (Fig. 3). In addition, the presence of any acute symptoms, the ability of a child to accept restorative care, and of course, any requirement for a general anaesthetic as part of their management, will have a significant influence on fundamental treatment planning decisions.17 Guidelines from the Faculty of Dental Surgery, Royal College of Surgeons of England, describe best practice on the timing, compensation and balancing of FPM extractions; however, the evidence base is generally low quality, with a preponderance of retrospective investigations currently populating the literature.22

In terms of interceptive extractions, predictors for successful eruption of the second permanent molar have always been more important in the mandibular arch. Classically, the child should have a Class I malocclusion and be between the ages of 8-10 years old to ensure minimal disruption to occlusal development. In addition, radiographic evidence of the second permanent molar unerupted in alveolar bone and early mineralisation of the bifurcation represent an optimal time for FPM extraction to ensure a good eruptive position of the second molar.23,24 More recent evidence would suggest that the window of opportunity in relation to radiographic development of the second permanent molar is wider in terms of bifurcation mineralisation, and that the mesiodistal angulation of these teeth and presence of a third permanent molar can offer further useful prediction of favourable second permanent molar eruption.19,20,25 All these predictive factors are more relevant in the mandibular arch, as the maxillary second permanent molar will generally achieve a good eruptive position over a wider range of extraction timings.18,19,20 In terms of interceptive treatment, routine balancing extraction of a sound FPM to preserve a dental centreline is not recommended. Compensating extraction of a sound upper FPM has been suggested to prevent over-eruption of this tooth when extraction of the lower FPM is required. For an upper FPM that will remain unopposed for some time, significant over-eruption can cause interferences with the erupting lower second permanent molar, impeding space closure and potentially contributing to other occlusal interferences. Current evidence would suggest that the risk of upper FPM over-eruption, as a consequence of lower FPM extraction, is small, and decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis.26

The widespread use of modern fixed appliances and fixed anchorage in orthodontics has meant that the incorporation of FPM extractions has become more routine in the management of malocclusion.27,28 Indeed, with radiographic evidence of third permanent molar development and a requirement for extraction-based fixed appliance treatment, the presence of caries, MIH, or a restoration in any FPM should elicit serious consideration of its elective extraction as part of an orthodontic treatment plan incorporating fixed appliances. When considering orthodontic treatment, there is no doubt that occlusal outcomes are generally easier to control in Class I cases, and those cases associated with any degree of sagittal discrepancy that are at the milder end of the spectrum. In general, the higher the anchorage requirements, the more difficult FPM extraction cases become to manage with fixed appliances, particularly those associated with the presence of a significant overjet and/or crowding. The reliance upon anchorage reinforcement with headgear, transpalatal arches and mini implants becomes more important for achieving a successful outcome, particularly in the older child (Fig. 4). However, depending upon severity of the malocclusion, even poorly positioned second permanent molars can be relatively easily managed with fixed appliances (Fig. 5). Space closure can be prolonged, particularly in the mandibular arch, but careful anchorage management and patient mechanics can produce good occlusal results, even in the adult dentition (Fig. 6).

a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h) A 15-year-old child with a challenging Class II Division 2 malocclusion complicated by the presence of a significant sagittal discrepancy, severe crowding and compromised FPMs, being treated with fixed appliances. A transpalatal arch and Nance button have been placed but the anchorage demand remains high

a, b, c, d) A 14-year-old Class I case with absent maxillary lateral incisors and previous interceptive extraction of all four FPMs. The eruptive position of the second permanent molars is poor in all four quadrants with generalised spacing present; however, the relatively mild nature of the malocclusion means that alignment and space closure is easily achievable with fixed appliance treatment

It should also be remembered that for some children presenting in the established permanent dentition with high caries risk and/or poor oral hygiene, fixed appliances might not be appropriate and sometimes compromises will need to be made when FPMs cannot be restored.

Patient perspectives and oral quality of life

Within the dental literature, there is growing emphasis on how dental conditions may impact on children's oral and general health-related quality of life. It is now well-recognised that both untreated caries and MIH can have profoundly negative impacts on a child's social, emotional and functional wellbeing.1,29 More research is needed to better understand how interventions can improve patient-reported outcomes and experiences for children with compromised FPMs, both in the short- and long-term.10

Conclusion

Compromised FPMs can have a negative impact on a child's quality of life and present significant management challenges for the dental team. Although a high-quality evidence base is still lacking to support all the different treatment options, early diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment planning are key to achieving the best possible outcomes.

References

Moghaddam L F, Vettore M V, Bayani A et al. The Association of Oral Health Status, demographic characteristics and socioeconomic determinants with Oral health-related quality of life among children: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Paediatr 2020; 20: 489.

UK Government. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2021. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention (accessed January 2023).

Taylor G D, Pearce K F, Vernazza C R. Management of compromised first permanent molars in children: Cross-Sectional analysis of attitudes of UK general dental practitioners and specialists in paediatric dentistry. Int J Paediatr Dent 2019; 29: 267-280.

UK Government. Children's dental health survey: 2013. 2015. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/childrens-dental-health-survey-2013 (accessed January 2023).

Rodd H D, Graham A, Tajmehr N, Timms L, Hasmun N. Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation: Current Knowledge and Practice. Int Dent J 2021; 71: 285-291.

Oreano M D, Santos P S, Borgatto A F, Bolan M, Cardoso M. Association between dental caries and molar-incisor hypomineralisation in first permanent molars: A hierarchical model. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2022; DOI: 10.1111/cdoe.12778.

Schwendicke F, Elhennawy K, Reda S, Bekes K, Manton D J, Krois J. Global burden of molar incisor hypomineralization. J Dent 2018; 68: 10-18.

Lygidakis N A, Garot E, Somani C, Taylor G D, Rouas P, Wong F S L. Best clinical practice guidance for clinicians dealing with children presenting with molar-incisor-hypomineralisation (MIH): an updated European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry Policy Document. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2021; 23: 3-21.

Walshaw E G, Noble F, Conville R, Lawson J A, Hasmun N, Rodd H. Molar incisor hypomineralisation and dental anomalies: A random or Real Association? Int J Paediatr Dent 2020; 30: 342-348.

Somani C, Taylor G D, Garot E, Rouas P, Lygidakis N A, Wong F S L. An update of treatment modalities in children and adolescents with teeth affected by molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH): A systematic review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2022; 23: 39-64.

Schwendicke F, Walsh T, Lamont T et al. Interventions for treating cavitated or dentine carious lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013039.pub2.

Duncan H F, Galler K M, Tomson P L et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Management of deep caries and the exposed pulp. Int Endod J 2019; 52: 923-934.

Taylor G D, Vernazza C R, Abdulmohsen B. Success of endodontic management of compromised first permanent molars in children: A systematic review. Int J Paediatr Dent 2019; 30: 370-380.

Rodríguez-Farre E, Testai E, Bruzell E et al. The safety of dental amalgam and alternative dental restoration materials for patients and users. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2016; 79: 108-109.

Elhennawy K, Jost-Brinkmann P-G, Manton D J, Paris S, Schwendicke F. Managing molars with severe molar-incisor hypomineralization: A cost-effectiveness analysis within German Healthcare. J Dent 2017; 63: 65-71.

Jälevik B, Klingberg G. Treatment outcomes and dental anxiety in 18-year-olds with MIH, comparisons with healthy controls - A longitudinal study. Int J Paediatr Dent 2011; 22: 85-91.

Ashley P, Noar J. Interceptive extractions for first permanent molars: A clinical protocol. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 192-195.

Nordeen K A, Kharouf J G, Mabry T R, Dahlke W O, Beiraghi S, Tasca A W. Radiographic Evaluation of Permanent Second Molar Substitution After Extraction of Permanent First Molar: Identifying Predictors for Spontaneous Space Closure. Paediatr Dent 2022; 44: 123-130.

Teo T K, Ashley P F, Parekh S, Noar J. The evaluation of spontaneous space closure after the extraction of first permanent molars. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2013; 14: 207-212.

Patel S, Ashley P, Noar J. Radiographic prognostic factors determining spontaneous space closure after loss of the permanent first molar. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2017; 151: 718-726.

Innes N, Borrie F, Bearn D et al. Should I eXtract Every Six dental trial (SIXES): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013; 14: 59.

Royal College of Surgeons of England. A guideline for the extraction of first permanent molars in children. 2023. Available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/fds/guidance-for-the-extraction-of-first-permanent-molars-in-children.pdf (accessed April 2023).

Thilander B, Skagius S. Orthodontic sequelae of extraction of permanent first molars. A longitudinal study. Rep Congr Eur Orthod Soc 1970; 429-442.

Normando A D, Maia F A, Ursi W J, Simone J L. Dentoalveolar changes after unilateral extractions of mandibular first molars and their influence on third molar development and position. World J Orthod 2010; 11: 55-60.

Yavuz I, Baydaş B, Ikbal A, Dağsuyu I M, Ceylan I. Effects of early loss of permanent first molars on the development of third molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006; 130: 634-638.

Jälevik B, Möller M. Evaluation of spontaneous space closure and development of permanent dentition after extraction of hypomineralized permanent first molars. Int J Paediatr Dent 2007; 17: 328-335.

Sandler P J, Atkinson R, Murray A M. For Four sixes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 117: 418-434.

DiBiase A, Sandler C, Sandler P J. For four sixes, revisited. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2021; DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.11.035.

Elhennawy K, Rajjoub O, Reissmann D R et al. The association between molar incisor hypomineralization and oral health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Investig 2022; 26: 4071-4077.

Acknowledgements

The Faculty of Dental Surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons of England and British Dental Journal have teamed up to provide this paper as part of a regular series of short articles on different aspects of clinical and academic dentistry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Martyn T. Cobourne and Helen Rodd conceived the article. Shrita Lakhani, Fiona Noble, Helen Rodd and Martyn T. Cobourne wrote and revised the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2023

About this article

Cite this article

Lakhani, S., Noble, F., Rodd, H. et al. Management of children with poor prognosis first permanent molars: an interdisciplinary approach is the key. Br Dent J 234, 731–736 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5816-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5816-7