Abstract

Introduction

We present a case describing the management of a woman with severe, functionally limiting cervical myeloradiculopathy in the setting of congenital cervical canal stenosis and Arnold–Chiari I malformation.

Case presentation

The subject is a 57-year-old woman with prior anterior cervical discectomy and fusion who presented with left-sided neck pain associated with radiculopathy, migraine, gait incoordination, and cervical dystonia. Cervical stenosis and Chiari malformation were confirmed using MRI. Conservative management with botulinum toxin, oral muscle relaxants, and cervical brace led to gradual exacerbation of symptoms. Due to failure of conservative management, surgical decompression with C3–C6 posterior laminoplasty was performed, resulting in complete resolution of all symptoms and markedly improved quality of life.

Discussion

This case reports a severe and nonspecific presentation of cervical myeloradiculopathy. Surgery for cervical myeloradiculopathy is controversial, and conservative therapy is initially preferred. However, in this case, conservative treatments likely led to paraspinal weakness, cervical hypermobility, and biomechanical instability, resulting in exacerbation of symptoms. Stretch/shear forces have been postulated to accelerate cervical myelopathy, and excessive cervical instability and range of motion are significant predictors of deterioration. In this case, surgical decompression with posterior cervical laminoplasty after 1 year of conservative management yielded significant pain relief and functional restoration, indicating the utility of this procedure even in the presence of Arnold–Chiari I malformation. This case illustrates that decompression can be effective for refractory cervical myeloradiculopathy associated with Chiari malformation, congenital stenosis, and prior anterior instrumentation, and highlights the potential risks of prolonged conservative management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic neck pain is a common complaint in the adult population. It is the fourth leading cause of disability and spinal dysfunction in older adults with an annual prevalence exceeding 30% [1]. Among the various etiologies of neck pain, cervical myelopathy due to pathological compression of the spinal cord is a serious condition characterized by markedly decreased quality of life in all SF-36 domains of health [2]. It is thought to be due to progressive spondylotic degeneration superimposed on a degree of congenital stenosis, with some studies arguing for an ischemic and/or biomechanical pathophysiology as well [3, 4]. In some cases, cervical myelopathy can be caused by Chiari I malformation, secondary to compression from cerebellar tonsillar herniation [5].

The diagnosis of cervical myelopathy is challenging. First, rather than having well-defined pathognomonic findings, a wide variety of nonspecific signs and symptoms, including upper-extremity sensory complaints, weakness, spasticity, gait disturbance, and bowel/bladder dysfunction, are linked to the disorder [6]. Second, radiographic evidence is not a reliable indicator of cervical myelopathy and its severity, with high degrees of degenerative and compressive changes present in many asymptomatic individuals [4]. Cervical myelopathy can also occur in concurrence with radiculopathy––termed “myeloradiculopathy”––due to the extension of degenerative compression onto adjacent nerve roots [6]. Due to the extensive differential diagnoses for neck pain and the overlapping, multifaceted diagnostic findings, cervical myelopathy is frequently misdiagnosed and improperly managed [5]. The natural history of this condition is difficult to predict but is generally characterized by progressive or stepwise deterioration with very rare spontaneous regression [7,8,9]. In many instances, symptoms can be brought on by minor trauma, especially in asymptomatic patients with prolonged radiographic signs of pathologic compression [4].

Surgical decompression has historically been the gold standard of treatment for symptomatic cervical myelopathy. Different approaches are chosen based on presenting signs, prior surgical history, preoperative spinal curvature, number of levels involved, and degree of spondylosis in adjacent levels, with earlier intervention typically yielding better outcomes [10]. However, there are limited cases reported of patients with simultaneous cervical canal stenosis and Chiari malformation, with each case utilizing different decompressive techniques [11, 12]. Furthermore, there is an argument that conservative management (rest, cervical immobilization, physiotherapy, etc.) is preferable to surgical management in milder forms of myelopathy, complicating the decision of when to perform surgery [13, 14].

We would therefore like to report a unique case of cervical myeloradiculopathy with associated Arnold–Chiari I malformation in which posterior cervical laminoplasty was successful after extensive conservative management had failed. We also highlight the risks of botulinum toxin, muscle relaxant, and neck immobilization therapies in patients with congenital stenosis.

Patient consent was obtained and de-identified data were used for this report.

Case presentation

In June 2015, a 57-year-old woman with a history of Arnold–Chiari type I malformation and congenital cervical canal stenosis presented to an orthopedic clinic with left neck pain, which began in May 2013 after her grandmother fell on her. The pain was described as constant, burning, 10/10 in severity, radiating down her left arm, worsened by straining and twisting, and inadequately controlled with opioid medication. Associated symptoms included left-arm weakness, numbness and tingling, neck stiffness, and gait incoordination. In 2008, she had reported similar symptoms on her right side, for which she underwent C5–C6 anterior discectomy and fusion with successful resolution of all complaints. She also reported histories of back pain, frequent urination (every 2 h), constipation, and diarrhea, but denied bowel or bladder incontinence. In 2013, she was diagnosed with migraines and had since been receiving botulinum toxin injections every 3 months. She attempted physical therapy (neck-stabilization protocol) in 2014, but the rotational exercises significantly exacerbated her neck pain, stiffness, and balance, causing her to discontinue.

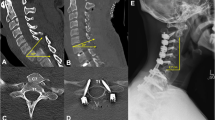

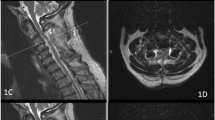

On examination, the woman’s neck was supple and non-tender. The range of motion was limited. Cervical facet loading and Spurling test did not exacerbate her symptoms. The left trapezius was larger than the right and exhibited bony-mass-like hardness. Cranial nerve exam was intact. Neurological exam was conducted in reference with the ASIA/ISCoS International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI), and revealed 4/5 strength bilaterally in all tested muscle groups (biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, hip flexors/extensors, knee flexors/extensors, and ankle dorsiflexors/plantar flexors), patellar hyperreflexia (3+), and intact sensation to light touch in all extremities. Her gait was wide-based. Cervical MRI revealed evidence of prior C5–C6 anterior fusion with diffuse congenital narrowing and mild degenerative changes throughout. EMG studies revealed no electrophysiological evidence of peripheral neuropathies or cervical radiculopathies involving either arm. Based on these findings, the woman was diagnosed with cervical myeloradiculopathy.

Conservative management was begun with close follow-up by physiatry–pain management, orthopedic surgery, and neurology. As part of her pain medication regimen, the woman was prescribed oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg every 8 h and baclofen 10 mg once a day. She declined physical therapy (neck-stabilization protocol) due to pain and balance exacerbation in the past and was prescribed a home-exercise program. A few months later, the woman was diagnosed with cervical dystonia and was prescribed a soft collar neck brace. She continued to receive the botulinum toxin injections for migraines, but starting from November 2015, these no longer provided relief but rather exacerbated her pain and caused transient dropped-head syndrome. After a year, the woman reported that her pain was worse. It was postulated that this was due to paraspinal instability caused by long-term use of botulinum toxin, oral muscle relaxants, and cervical immobilization in the setting of existing canal stenosis. Neurosurgical workup ruled out Chiari malformation as the cause of the symptoms, and further neurological workup ruled out cervical dystonia. The woman was encouraged to discontinue botulinum toxin, muscle relaxant, and neck brace therapies, avoid neck extension, and cautiously restart neck-strengthening exercises over the next few months to prepare for surgery. She was compliant with the exercise regimen and regained adequate strength for surgical clearance. C3–C6 posterior cervical laminoplasty was scheduled. Risks, benefits, and alternatives were communicated, and informed consent was obtained.

The procedure was completed without any significant complications. At the 2-week postoperative visit, the woman reported significant relief and improvement. She no longer had headaches, neck pain, numbness/tingling, radiculopathy, or gait incoordination. On examination, she reported mild paraspinal tenderness and range of motion limitation, which was expected after her surgery and subsequently resolved. Muscle strength was now 5/5 throughout her upper and lower extremities. Her gait and balance were improved. She reported no new incontinence or changes in bowel/bladder function. Six months post-op, she continues to be asymptomatic with marked functional improvement, and has been able to discontinue her oxycodone/acetaminophen and baclofen medications.

Discussion

This case illustrates a diagnostic dilemma with multiple explanations for this woman’s radiating neck pain, while highlighting the benefits of laminoplasty and the risks of conservative therapy in the setting of congenital stenosis. Cervical myelopathy with radicular features best fits the presentation, but comorbidities such as migraine, Chiari malformation, and cervical dystonia, as well as a history of myelopathy s/p discectomy and fusion complicated efforts to distill the underlying etiology. Furthermore, even with cervical myeloradiculopathy identified, it was unclear whether the compression was secondary to the canal stenosis or Chiari malformation, as both can lead to variable, overlapping presentations of neck pain, radiculopathy, gait disturbances, migraine-like headache, and para-axial stiffness. In fact, one study shows that in several patients previously diagnosed with fibromyalgia, MRI revealed either Arnold–Chiari I malformation or cervical spondylotic myelopathy as the true etiology of their pain [5], illustrating the extensive, nonspecific distribution of symptoms between these two conditions.

In addition to the absence of definitive evidence for a specific etiology, we found no guidelines in the literature as to the best management approach in this woman’s specific scenario. Similar cases with concurrent Chiari malformation and spondylotic myelopathy have been reported, but the recommendations were not readily transferrable. For example, Bullock et al. reported that a 79-year-old female with comorbid Chiari I malformation and cervical spondylotic myelopathy successfully underwent combined foramen magnum decompression and C5 skip laminectomy, with complete resolution of symptoms. However, while a novel and promising technique, skip laminectomy has not yet been well characterized in the literature and congenital narrowing is a purported contraindication [15, 16]. In another example, posterior laminectomy surgery was successful in relieving myelopathic pain and gait incoordination in a 55-year-old female, who had both C5–C6 anterior discectomy with fusion and decompression surgery for Chiari I malformation many years earlier [11]. However, in our patient, the Chiari malformation had not been previously decompressed, rendering this recommendation less applicable.

Given the lack of applicable evidence-based surgical guidelines, we chose to begin with conservative management. It has been shown that conservative management, specifically neck immobilization, is appropriate in a patient with clinically stable findings of myelopathy without signs of deterioration, and that attempting surgical decompression after signs of deterioration appeared was not too late [4, 13]. Nonoperative management has also been shown to be beneficial in mild cases of Chiari I malformation, with some patients even showing modest improvement in one study [17].

Our patient’s subsequent symptomatic deterioration with conservative treatment was likely due to the fact that neck immobilization, oral muscle relaxant use, and botulinum toxin therapy resulted in paraspinal weakness that, with avoidance of physical therapy, led to cervical hypermobility and biomechanical instability. This, in turn, exacerbated the pathological effect of her preexisting canal stenosis. Stretch and shear forces on the cord have been postulated to trigger or even be a primary etiology of cervical myelopathy, and excessive instability and range of motion are two of the most significant predictors of deterioration in the natural history of the disease [3, 13]. The woman’s symptomatic exacerbation in this setting also suggested that her presentation was due to cervical stenosis rather than to downward compression by the Chiari malformation, and this was confirmed by a neurosurgical evaluation.

After conservative treatment for 1 year had failed and Chiari was ruled out as the cause, surgical decompression at the C3–C6 vertebral levels was pursued. Due to the number of levels involved, prior anterior fusion, and the absence of preoperative kyphosis, a posterior approach was most appropriate. Although the aforementioned case reports had utilized the laminectomy technique, a laminoplasty procedure was performed in this case due to decreased risk of postoperative kyphosis and instability, better preservation of range of motion, no risk of nonunion or instrument failure, and the surgeon’s familiarity with the procedure [18]. After the operation, the woman reported complete resolution of all symptoms with only minor procedure-related pain and range of motion limitation.

While decompression was successful in this case, the evidence we present cannot yet be generalized to scenarios other than the one specifically outlined here. Further studies are required to assess the risks of prolonged conservative treatment in cervical canal stenosis, improve diagnostic strategies to identify the cause of a patient’s myeloradiculopathy, and outline the optimum surgical management in patients with comorbid myelopathy, canal stenosis, and Arnold–Chiari I malformation. Furthermore, the woman in the case has not yet been followed for a sufficient postoperative duration to extrapolate long-term outcomes––one of the purported shortcomings of surgical management for cervical myelopathy. However, the primary goal of decompression surgery in cervical myelopathy is to increase the quality of life, not necessarily to permanently cure the condition [19]. In a person with chronic pain, relief for even a limited extended period can dramatically improve the ability to function and experience life positively. While we cannot predict her long-term postoperative course beyond 6 months, we still believe that this woman’s remarkable clinical improvement is a noteworthy success.

In this case report, we presented a unique and perplexing case that, due to multiple comorbidities and lack of literature, was difficult to optimally diagnose and manage. After extended conservative treatment had failed, surgical decompression with posterior cervical laminoplasty resulted in complete pain relief, discontinuation of all opioid medications, and significantly improved quality of life. We hope that this report will be useful to other spine practitioners and contribute to the growing pool of research on cervical myelopathy, as well as to help relieve pain and restore function to a unique subset of patients (Figs. 1 and 2).

Sagittal a preoperative and b postoperative cervical spine X-ray imaging of a 57-year-old woman with prior anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, in neutral neck position. Postoperative imaging shows laminoplasty plates at C4, C5, and C6 posteriorly with good implant positioning and increased distance between the spinous process and lamina

References

Cohen SP. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of neck pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:284–99.

King JT, McGinnis KA, Roberts MS. Quality of life assessment with the medical outcomes study short form-36 among patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:113–20.

Henderson FC, Geddes JF, Vaccaro AR, Woodard E, Berry KJ, Benzel EC. Stretch-associated injury in cervical spondylotic myelopathy: new concept and review. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1101–13.

Orr RD, Zdeblick TA. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: approaches to surgical treatments. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;359:58–66.

Heffez DS, Ross RE, Shade-zeldow Y, Kostas K, Shah S, Gottschalk R, et al. Clinical evidence for cervical myelopathy due to Chiari malformation and spinal stenosis in a non-randomized group of patients with the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:516–23.

Harrop JS, Hanna A, Silva MT, Sharan A. Neurological manifestations of cervical spondylosis: an overview of signs, symptoms, and pathophysiology. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:S14–20.

Baron EM, Young WF. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a brief review of its pathophysiology, clinical course, and diagnosis. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:S35–41.

Karadimas SK, Erwin WM, Ely CG, Dettori JR, Fehlings MG. Pathophysiology and natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2013;38:S21–36.

Murphy DR, Beres JL. Cervical myelopathy: a case report of a “near-miss” complication to cervical manipulation. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2008;31:553–7.

Mummaneni PV, Kaiser MG, Matz PG, Anderson PA, Groff MW, Heary RF, et al. Cervical surgical techniques for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2009;11:130–41.

Klekamp J. Surgical treatment of multilevel cervical spondylosis in patients with or without a history of syringomyelia. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:948–57.

Bullock M, Kanatas A, Pal D, Towns G. A diagnostic dilemma: cervical myelopathy in the presence of chiari 1 malformation and multi-level cord compression in a 79-year-old woman. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:231–4.

Kong LD, Meng LC, Wang LF, Shen Y, Wang P, Shang ZK. Evaluation of conservative treatment and timing of surgical intervention for mild forms of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:852–6.

Nikolaidis I, Fouyas IP, Sandercock PA, Statham PF. Surgery for cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;20:CD001466.

Sivaraman A, Bhadra AK, Altaf F, Singh A, Rai A, Casey AT, et al. Skip laminectomy and laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a prospective study of clinical and radiologic outcomes. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2010;23:96–100.

Shiraishi T, Fukuda K, Yato Y, Nakamura M, Ikegami T. Results of skip laminectomy-minimum 2-year follow-up study compared with open-door laminoplasty. Spine. 2003;28:2667–72.

Killeen A, Roguski M, Chavez A, Heilman C, Hwang S. Non-operative outcomes in Chiari I malformation patients. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:133–8.

Chang H, Kim C, Choi BW. Selective laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a comparative analysis with laminoplasty technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137:611–6.

Yamazaki T, Yanaka K, Sato H, Uemura K, Tsukada A, Nose T. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: surgical results and factors affecting outcome with special reference to age differences. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:122–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank the medical staff at Restore Orthopedics and Spine Center for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohan, A., Chang, E. Decompression for botulinum toxin-exacerbated cervical myeloradiculopathy in the setting of congenital stenosis and Arnold–Chiari I malformation. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4, 42 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0077-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0077-4