Abstract

Background

Inequity in neonatology may be potentiated within neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) by the effects of bias. Addressing bias can lead to improved, more equitable care. Understanding perceptions of bias can inform targeted interventions to reduce the impact of bias. We conducted a mixed methods study to characterize the perceptions of bias among NICU staff.

Methods

Surveys were distributed to all staff (N = 245) in a single academic Level IV NICU. Respondents rated the impact of bias on their own and others’ behaviors on 5-point Likert scales and answered one open-ended question. Kruskal–Wallis test (KWT) and Levene’s test were used for quantitative analysis and thematic analysis was used for qualitative analysis.

Results

We received 178 responses. More respondents agreed that bias had a greater impact on others’ vs. their own behaviors (KWT p < 0.05). Respondents agreed that behaviors were influenced more by implicit than explicit biases (KWT p < 0.05). Qualitative analysis resulted in nine unique themes.

Conclusions

Staff perceive a high impact of bias across different domains with increased perceived impact of implicit vs. explicit bias. Staff perceive a greater impact of others’ biases vs. their own. Mixed methods studies can help identify unique, unit-responsive approaches to reduce bias.

Impact

-

Healthcare staff have awareness of bias and its impact on their behaviors with patients, families, and staff.

-

Healthcare staff believe that implicit bias impacts their behaviors more than explicit bias, and that they have less bias than others.

-

Healthcare staff have ideas for strategies and approaches to mitigate the impact of bias.

-

Mixed method studies are effective ways of understanding environment-specific perceptions of bias, and contextual assets and barriers when creating interventions to reduce bias and improve equity.

-

Generating interventions to reduce the impact of bias in healthcare requires a context-specific understanding of perceptions of bias among staff.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Racial and ethnic disparities, both between and within neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), exist in a variety of neonatal outcomes, processes, and quality measures.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Qualitative studies of former NICU patient families from minoritized backgrounds have identified experiences of racially biased judgmental care, disrespectful care, and poor communication. Families with limited English proficiency report lack of consistent high-quality interpreter services, and reduced discharge readiness, as well as decreased knowledge of post-NICU discharge health services, such as Early Intervention.9,10,11,12 Provider bias is a potential mechanism by which disparities in care within a single clinical context are propagated.13

Bias arises from the natural tendency of humans to create classifications as they attempt to rapidly process information. Bias exists as either explicit bias, the traditional conceptualization of bias in which individuals are aware of their own attitudes, or implicit bias, which is subconscious.14 High prevalence of healthcare provider bias has been reported, including anti-Black/pro-white bias among pediatricians.15,16,17,18,19 Furthermore, biases have been shown to worsen in the setting of provider burnout and increased cognitive stressors, fatigue, time limitations, and information overload, all of which are relevant contextual factors in the field of neonatology.19,20,21,22

Bias has a significant impact on healthcare decision making and outcomes.18 It is associated with reduced quality of patient–provider communication, reduced shared decision making, and diminished quality of the physician–patient relationship.23,24,25,26 In neonatology, implicit and explicit racial bias is associated with increased adverse birth outcomes for black infants and affects neonatologists’ recommendations during periviability counseling.27,28 However, bias can be reduced through the use of educational interventions, workshops, and clinical case conferences, and the impact of bias can be reduced through the use of equity-focused quality improvement.22,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 Knowledge of local context and individual attitudes can facilitate the creation of targeted interventions that avoid common pitfalls and address important aspects of workplace and healthcare system culture.

We sought to explore perceptions of the effect of bias on the care of infants, communication with families, and interprofessional interactions among all staff in our NICU to assess the culture and knowledge surrounding bias and inequity. Our study served to inform the development of projects to reduce the impact of bias and address health inequity. This study highlights perceptions of bias among NICU staff and demonstrates the feasibility and importance of using mixed methods approaches to assess healthcare culture and serve as the foundation for interventions to address health inequity.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional mixed methods study in a single urban academic level IV NICU. This study was designed to (1) understand perceptions of bias within a single NICU and (2) identify targets for interventions to reduce the impact of bias. We employed quantitative and qualitative methods, because the latter allows for the exploration of thoughts and beliefs including how individuals might respond to interventions.36

Eligible participants were defined as all staff who work in the NICU including neonatology and pediatric surgery attendings; neonatal-perinatal medicine, pediatric surgery, and pediatric critical care fellows; neonatal nurse practitioners; bedside nurses; respiratory therapists; nurse educators; unit coordinators; and environmental staff. We invited all eligible individuals to participate via an email that included a link to the optional, anonymous survey. All participants received reminder emails to complete the survey during the data collection period. Surveys were anonymous and de-identified in order to provide psychological safety and optimize study participation. This study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Survey

Our survey included three parts: (1) demographics, (2) assessing equity and the impact of bias, and (3) “How are we doing?” All survey questions were optional. The survey was initially developed by an investigator and underwent iterative revisions until consensus was reached by the study team, which included physician and nursing leadership, attending physicians, clinical fellows, and bedside nursing staff (the complete survey can be viewed in Supplementary Table 1).

In section one, we collected NICU role, years of experience (less than vs. greater than 10 years), gender, race, ethnicity, and age.

Section two was designed to explore perceptions of the impact of implicit and explicit bias on patient care, interactions with family, and professional colleagues. These three domains were selected based on prior research that explored the impact of bias on patients and their health outcomes, families, and interprofessional interactions,9,11,17,18,37,38,39 In addition, these domains can be targeted with interventions. We also sought to explore the degree to which respondents believed bias had an impact on their own vs. others’ behaviors. All response options were a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Definitions of bias, implicit bias, and explicit bias were provided in the survey in order to ensure shared knowledge and understanding among respondents. Respondents were asked to indicate patient or family qualities that they believe lead to bias.

Section three included four questions related to the NICU culture and commitment to reducing bias and achieving equity, followed by one open-ended question to share feelings, experiences, expectations, and examples of bias.

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at Boston Children’s Hospital.40,41 REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies.

Quantitative analysis

We performed Kruskal–Wallis test (KWT) and Levene’s test (LT) to assess the differences in median and variance of Likert scale responses, respectively. We compared the perceived impact of implicit vs. explicit bias and the impact of bias on one’s own compared to others’ behaviors. We used frequencies and percentages to describe areas felt to contribute to bias in care. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Qualitative analysis

Open-ended responses were reviewed by an individual not involved in the NICU to ensure anonymity. Identifying statements were redacted from the responses. We used a Grounded Theory approach, a standard qualitative analysis approach in which theory is derived from collected data. Grounded Theory is particularly valuable in areas of research where there is a paucity of prior data and thus was the approach selected for this study.36 Two research team members (C.C.C., Y.S.F.) independently coded responses, then jointly reviewed and combined codes into a final codebook reaching a consensus through discussions about disagreements. Codes were then iteratively organized into categories and themes. Dedoose Version 8.0.35 web application was used for managing and analyzing qualitative responses (Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC).

Results

Demographics

We received 178 survey responses (response rate: 73%). Participants identified predominantly as white (84%) and as cis-gendered females (87%) with a median age of 34 years (interquartile range 30–43). Of 162 individuals who identified their clinical roles, 84 were bedside nurses, 28 were clinical fellows, 24 were attendings, and 10 were neonatal nurse practitioners (Table 1).

Quantitative results

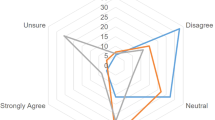

About half of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their own explicit bias could have an impact on the care they provide to infants (45%), interactions with families (56%), and interactions with staff (45%) (Fig. 1). When asked about the impact of explicit bias on others’ behaviors, 62%, 74%, and 65% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that explicit bias could have an impact on the care others provided to infants, interactions with families, and interactions with staff, respectively. Across all behavioral domains, a significantly higher proportion of individuals agree or strongly agreed that others’ behaviors were impacted by explicit bias more than their own (KWT p < 0.05, Table 2).

Regarding implicit bias, 56%, 69%, and 63% of respondents, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed that bias could have an impact on the care they provided to infants, their own interactions with families, and their own interactions with staff. A total of 71%, 79%, and 75%, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed that implicit bias could have an impact on the care provided to infants by others, others’ interactions with family, and others’ interactions with staff. Across all behavioral domains, more respondents agreed or strongly agreed that implicit bias impacted others’ behavior more than their own (KWT p < 0.05, Table 2).

Comparing the perception of the impact of explicit vs. implicit bias on one’s own behaviors, we found significant differences in median and variance (KWT p < 0.05 and LT p < 0.05) across all behavioral domains, indicating a greater perceived impact of implicit over explicit bias. There were no significant differences in the median perception of the impact of explicit vs. implicit bias on others’ behaviors. LT was statistically significant when comparing the perceived impact of explicit and implicit bias on infant care and interprofessional staff interactions. This indicates that though respondents perceive an overall equal impact of implicit and explicit bias on others’ behaviors, there was a significant difference in the variability of responses regarding the impact of implicit vs. explicit bias for patient care and interprofessional behaviors. There were no significant differences in responses across roles. (see results stratified by NICU role in Supplementary Table 2).

Socioeconomic status was the most frequently selected patient or family quality that respondents reported could lead to bias (N = 83, 64%), followed by an infant diagnosis of neonatal abstinence syndrome/neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (N = 75, 58%), race or ethnicity (N = 72, 56%), primary language (N = 70, 54%), religion or religious expression (N = 55, 43%), country of origin (N = 49, 38%), and family tobacco use (N = 39, 30%), family sexual orientations (N = 22, 17%), and family members with obesity (N = 22, 17%). Among all respondents, 14 individuals (11%) indicated that none of the patient or family qualities listed could lead to bias.

Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the culture of the NICU was committed to providing equitable care (N = 112, 89.6%). However, only 22% agreed or strongly agreed that (1) decreasing bias and promoting equity were priorities and (2) attempts had been made to decrease bias and promote equity. The majority of respondents (N = 102, 78.1%) agreed or strongly agreed that the NICU would benefit from a formal approach to reducing bias in care and promoting equity.

Qualitative results

We received 30 unique responses to the qualitative portion of our survey. Nine unique themes emerged from our analysis. Themes were then grouped into four major domains: (1) the impact of bias, (2) causes of bias, (3) strategies to mitigate bias, and (4) factors to consider when creating interventions (Table 3).

Under the domain of the impact of bias, themes demonstrated that bias has an impact on all individuals in the NICU, including both patients and staff. Under the domain of causes of bias, themes highlighted patient characteristics, as well as structural factors in the NICU, that led to the development of an environment that is permissive to bias. Themes demonstrated that staff had perceptions of what approaches would and would not be successful to mitigate bias. For example, staff were interested in learning techniques to speak up when instances of bias were witnessed, while some staff were concerned that without individual introspection interventions would not be successful. Finally, themes demonstrated the importance of personal experiences in understanding bias, as well as the varying degrees of enthusiasm for addressing and polarizing perceptions of bias.

Discussion

In this mixed methods study, we identified that the majority of NICU staff agree that both implicit and explicit bias can have an impact on their patient care, communication with families, and professional interactions with colleagues. Our results show that individuals perceived a greater impact of implicit than explicit bias across all care domains. In addition, a majority of individuals agreed that bias had an impact on others’ behaviors more than their own. We found that the most commonly perceived patient and family characteristics that lead to bias are socioeconomic status, infant diagnosis of neonatal abstinence syndrome/neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, race or ethnicity, and primary language. Our qualitative analysis highlighted that bias has an impact on all individuals including patients and staff, that there are structurally and personally mediated impacts of bias, and that individuals overwhelmingly desired interventions to mitigate the impact of bias on propagating neonatal inequity.

Together, the quantitative and qualitative results of our mixed methods study highlight knowledge, insights, and beliefs of NICU staff on issues of bias and equity. In particular, we found that NICU staff understand bias and believe it can have an impact on multiple behavioral domains, albeit with varying degrees of perceived effect. Potential hypotheses that explain the variation in the perceived effect of bias include varied exposure to anti-bias education among staff, varied levels of awareness among staff, or a lack of personal insight, supported by the difference in perceived impact of one’s own vs. others’ bias. Our study also highlights key areas of NICU culture pertaining to issues of bias and equity, such as staff diversity.

Results of mixed methods studies can inform interventions to reduce the impact of bias that are personalized and responsive to the clinical culture and environment. Our study identified that staff are self-aware of the impact of bias and interested in interventions to increase equity, indicating the readiness of change. We also identified barriers such as lack of insight into the impact of one’s own biases compared to others’, and lack of interest in interventions focused solely on education. In the future, these findings can be coupled with focus groups that include diverse, representative staff, including those who did not agree that bias can impact behaviors or who shunned interventions, to have a deeper understanding of the clinical environment and to develop effective, targeted, context-responsive interventions to reduce the impact of bias and preemptively avoid potential barriers.

While there is important generalizability in the findings of our study, the true strength of this work rests in the demonstration of the feasibility of asking difficult questions, assessing healthcare culture through mixed methods studies, and in translating findings into context-specific interventions designed to combat the ills of bias and systemic inequity.

The results of our study have directly informed multiple interventions within our NICU to decrease the impact of bias with the goal of increasing equity (Table 4). As a result of our study, we have established a multidisciplinary “Equity Working Group” that focuses on issues of patient, family, and staff equity within our NICU. Recognizing both the importance of increasing foundational knowledge and the utility of personal experiences in understanding the role of bias in promoting inequity, we have adapted existing case-based approaches that center on the experience of families to understand bias in the neonatal context and provide a combination of foundational knowledge and real-time skills to use when bias is witnessed.30 In addition, we have established multiple equity-focused quality improvement projects informed by the results of our study and that include patient and family stakeholders with aims such as decreasing time to first family meetings, increased breastmilk utilization, more timely access to social supports, and safe, standardized discharge planning. Finally, recognizing the importance of structural and systemic change within our NICU, we have focused on changing culture and increasing the diversity of our staff at all levels.

Our study is unique for two reasons. First, we used a multidisciplinary approach in our study planning, survey design, and dissemination strategy to ensure inclusivity in understanding culture. To our knowledge, this is the first study of bias in the healthcare setting that uses a multidisciplinary study team and population. Second, our study highlights the utility of mixed methods approaches to understanding perceptions and culture surrounding bias to inform targeted, specific, actionable interventions that seek to create equity by reducing the impact of bias. The utility of mixed methods approaches can identify perceived areas for interventions among staff to impact the clinical culture around bias. However, the inclusion of patient, family, and staff stakeholders, especially those from minoritized and disenfranchised backgrounds who are most likely to be impacted by bias, must be included in the development of such interventions.

Our study is limited by the small, demographically homogenous sample size and single-center design that limit the generalizability of our results. We had a high response rate, and the study population was well represented among the respondents. This was an asset to our study that sought to assess unit culture and generate targeted interventions specific to our NICU. However, because of the anonymous nature of our survey, we are unable to ascertain which key staff demographics are not represented in our study. In addition, we recognize that our specific findings may not be wholly generalizable, and results may vary in different contexts and among different populations. Importantly, the methodologies and approaches used to assess readiness for change, culture, and high-yield areas for intervention are generalizable to other healthcare contexts including those outside of the NICU. Further research is needed to understand the most optimal interventions to reduce bias, to study implemented interventions that claim to reduce bias, and most importantly, to explore the impact of interventions on downstream patient outcomes. In addition, we asked about individual perceptions of their own and others’ bias, but did not administer validated assessments, such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT), to assess the level of bias among respondents. While this would have allowed us to better quantify individual-level bias, our primary interest was to focus on culture and perceptions of bias in order to generate future interventions to reduce the impact of bias. Serial administration of the IAT may prove useful at later stages of our work to track the impact of interventions to reduce bias. Furthermore, studies have found that while there is no consistent correlation between explicit and implicit attitudes, individuals are able to accurately predict the results of their own IAT.42 In addition, asking about implicit attitudes and directing individuals to have increased awareness of their biases increases bias self-awareness to the same extent as the IAT.43 Thus, our study findings may be an appropriate proxy for the degree of implicit bias among individuals.

In conclusion, we found that the majority of NICU staff agree that their own and others’ implicit and explicit bias has an impact on patient care, family communication, and interprofessional interactions. In addition, through the use of qualitative study techniques, we identified nine unique themes surrounding issues of bias and equity. The results of our mixed methods study have formed the foundation of multiple targeted, unit-specific interventions to reduce the impact of bias in the NICU. Our study highlights the importance, generalizability, and applicability of mixed methods studies to reduce the impact of bias in healthcare settings.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sigurdson, K. et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics 144, e20183114 (2019).

Murosko, D., Passerella, M. & Lorch, S. Racial segregation and intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants. Pediatrics 145, e20191508 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in human milk Intake at neonatal intensive care unit discharge among very low birth weight infants in California. J. Pediatr. 218, 49–56.e3 (2020).

Parker, M. G. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mother’s milk feeding for very low birth weight infants in Massachusetts. J. Pediatr. 204, 134–141.e1 (2019).

Boghossian, N. S. et al. Racial and ethnic differences over time in outcomes of infants born less than 30 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics 144, e20191106 (2019).

Profit, J. et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics 140, e20170918 (2017).

Edwards, E. M. et al. Quality of care in US NICUs by race and ethnicity. Pediatrics 148, e2020037622 (2021).

Fraiman, Y. S., Stewart, J. E. & Litt, J. S. Race, language, and neighborhood predict high-risk preterm Infant Follow Up Program participation. J. Perinatol. 42, 217–222 (2022).

Sigurdson, K. et al. Former NICU families describe gaps in family-centered care. Qual. Health Res. 30, 1861–1875 (2020).

Martin, A. E., D’Agostino, J. A., Passarella, M. & Lorch, S. A. Racial differences in parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care unit nursing care. J. Perinatol. 36, 1001–1007 (2016).

Sigurdson, K., Morton, C., Mitchell, B. & Profit, J. Disparities in NICU quality of care: a qualitative study of family and clinician accounts. J. Perinatol. 38, 600–607 (2018).

Miquel-Verges, F., Donohue, P. K. & Boss, R. D. Discharge of infants from NICU to Latino families with limited English proficiency. J. Immigr. Minor Health 13, 309–314 (2011).

Nieblas-Bedolla, E., Christophers, B., Nkinsi, N. T., Schumann, P. D. & Stein, E. Changing how race is portrayed in medical education: recommendations from medical students. Acad. Med. 95, 1802–1806 (2020).

U.S. Department of Justice. Community relations services toolkit for policing: understanding bias: a resource guide bias policing overview and resource guide. https://www.justice.gov/file/1437326/download.

Phelan, S. et al. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: the medical student CHANGES study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22, 1201–1208 (2014).

Hall, W. J. et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 105, e60–e76 (2015).

Maina, I. W., Belton, T. D., Ginzberg, S., Singh, A. & Johnson, T. J. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc. Sci. Med. 199, 219–229 (2018).

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R. & Oliver, M. N. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4296–4301 (2016).

Johnson, T. J. et al. The impact of cognitive stressors in the emergency department on physician implicit racial bias. Acad. Emerg. Med. 23, 297–305 (2016).

Dyrbye, L. et al. Association of racial bias with burnout among resident physicians. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e197457 (2019).

Profit, J. et al. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual. Saf. 23, 806–813 (2014).

Schnierle, J., Christian-Brathwaite, N. & Louisias, M. Implicit bias: what every pediatrician should know about the effect of bias on health and future directions. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 49, 34–44 (2019).

Hagiwara, N. et al. Racial attitudes, physician-patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc. Sci. Med. 87, 123–131 (2013).

Hagiwara, N., Slatcher, R. B., Eggly, S. & Penner, L. A. Physician racial bias and word use during racially discordant medical interactions. Health Commun. 32, 401–408 (2017).

Cooper, L. A. et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am. J. Public Health 102, 979–987 (2012).

Blair, I. V. et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann. Fam. Med. 11, 43–52 (2013).

Orchard, J. & Price, J. County-level racial prejudice and the black-white gap in infant health outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 181, 191–198 (2017).

Shapiro, N., Wachtel, E. V., Bailey, S. M. & Espiritu, M. M. Implicit physician biases in periviability counseling. J. Pediatr. 197, 109–115.e1 (2018).

Stone, J. & Moskowitz, G. B. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: What can be done to reduce it? Med. Educ. 45, 768–776 (2011).

Perdomo, J. et al. Health equity rounds: an interdisciplinary case conference to address implicit bias and structural racism for faculty and trainees. MedEdPORTAL 15, 10858 (2019).

Stone, J., Moskowitz, G. B., Zestcott, C. A. & Wolsiefer, K. J. Testing active learning workshops for reducing implicit stereotyping of Hispanics by majority and minority group medical students. Stigma Health 5, 94–103 (2020).

Leslie, K. et al. Changes in medical student implicit attitudes following a health equity curricular intervention. Med. Teach. 40, 372–378 (2018).

Devine, P., Forscher, P., Austin, A. & Cox, W. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: a prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1267–1278 (2012).

Trent, M., Dooley, D. G. & Dougé, J. Section on Adolescent Health; Council on Community Pediatrics; Committee on Adolescence The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics 144, e20191765 (2019).

Reichman, V., Brachio, S. S., Madu, C. R., Montoya-Williams, D. & Peña, M. M. Using rising tides to lift all boats: equity-focused quality improvement as a tool to reduce neonatal health disparities. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 26, 101198 (2021).

Austin, Z. & Sutton, J. Qualitative research: getting started. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 67, 436–440 (2014).

FitzGerald, C. & Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 18, 19 (2017).

Roiek, A. E. et al. Differences in narrative language in evaluations of medical students by gender and under-represented minority status. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 684–691. (2019).

Palepu, A. et al. Minority faculty in academic rank in medicine. JAMA 280, 767–771 (1998).

Harris, P. A. et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 95, 103208 (2019).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Hahn, A., Judd, C., Hirsh, H. & Blair, I. Awareness of implicit attitudes. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143, 1369–1392 (2014).

Hahn, A. & Gawronski, B. Facing one’s implicit biases: from awareness to acknowledgment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116, 769–794 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the respondents to our survey without whom this work would not be possible. We acknowledge Isabelle Smith for the initial review and editing of survey responses to maintain anonymity.

Funding

Y.S.F. was supported by AHRQ grant number T32HS000063 as part of the Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.F. conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, completed all analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. C.C.C. participated in the qualitative analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. K.T.L., and A.R.H., and D.M. designed the data collection instruments, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Individuals provided implied written consent by returning the completed optional surveys. No additional consent was required by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fraiman, Y.S., Cheston, C.C., Morales, D. et al. A mixed methods study of perceptions of bias among neonatal intensive care unit staff. Pediatr Res 93, 1672–1678 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02217-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02217-2

This article is cited by

-

Parent and staff perceptions of racism in a single-center neonatal intensive care unit

Pediatric Research (2024)

-

Equity, inclusion and cultural humility: contemporizing the neonatal intensive care unit family-centered care model

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

Disparity drivers, potential solutions, and the role of a health equity dashboard in the neonatal intensive care unit: a qualitative study

Journal of Perinatology (2023)