Abstract

Background

Life events and parenting styles might play an important role in children’s mental health.

Aims

This study aims to explore how life events and parenting styles influence children’s mental health based on a Chinese sample.

Methods

A total of 3535 participants had at least one mental disorder (positive group), while a total of 3561 participants had no mental disorders (negative group). The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Check List (ASLEC) and Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran (EMBU) were used for screening these two groups.

Results

CBCL total scores differed significantly by sex in the Positive group according to the Mann–Whitney tests (Z = −5.40, p < 0.001). Multiple regression analyses showed that the dimensions of punishment (p = 0.014) and other (p = 0.048) in the ASLEC scale can significantly predict CBCL total scores in the Positive group. Sex, age and overprotection from the father were risk factors (p < 0.001) according to binary logistic regression.

Conclusions

Life events and parenting styles may have impacts on mental health. Fathers play a very important role in children’s growth. Punitive education and fathers’ overprotection might be risk factors for children’s mental health.

Impact

-

It is a large sample (3535) study of Chinese children and adolescents

-

It provides evidence that life events and parenting styles have impacts on mental health and that fathers play a very important role in children’s growth.

-

It is conducive to the development of interventions for the mental health of children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health is an essential part of children’s development. Mental problems are prevalent in children and adolescents, and many mood disorders in adults are driven from childhood1. China has a population of 420 million children aged 0-14 years2. This indicates that as many as 20% of children and adolescents endure mental disorders in China3,4,5. This means that nearly 84 million children and adolescents in China may be at risk of psychological problems. Mental disorders result from the interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors6,7,8. Regarding psychological and social factors, life events and parenting styles might contribute significantly to mental health for children and adolescents8,9,10,11. However, parents in China may pay more attention to children’s physical symptoms12,13 rather than mental symptoms, including anxiety, depression, conduct disorders, and other disorders14,15. The current situation of mental health for children and adolescents seems to be neglected.

Recently, the influence of life events on mental health in children and adolescents has been confirmed in several studies10,16,17. A life event is a kind of psychosocial stressor, including encounters in daily life, work, and study18. In addition, life events can exert a negative influence on mental health18,19. Negative life events are related to suicidal thoughts, attempts, and completed suicide20,21. Children’s and adolescents’ negative life events are related to the occurrence and development of some psychosomatic diseases and affect emotions and behavior in adulthood22. Previous studies have reported that reducing negative life events can alleviate emotional and behavioral problems. Therefore, identifying the distinct stressors that are more strongly associated with mental disorders might be very important for the mental health of children and adolescents.

Furthermore, parenting style was seen as a cavalcade of attitudes and behaviors that parents toward children23. Well-confirmed links were found between parenting style and parent-adolescent relationship qualities24. The parent-adolescent relationship creates different personality characteristics for teenagers23,25. Consequently, the occurrence and development of mental disorders might also be influenced by parenting style26. A negative parenting style is a risk factor for emotional problems such as anxiety and depression27. The dimension of rejection, emotional warmth and overprotection in parenting is considered the most important factor in a sample of Chinese high school students28. However, most of these studies have a limited sample size. A larger sample is needed to present the confirmed associations between parenting style and mental health in children and adolescents.

Taken together, life events and parenting styles might be regarded as important factors for the mental health of children and adolescents. We might need to investigate the “risk factor” (which has a negative impact on mental health) (i.e., life events and negative parenting style). However, few studies have reported the associations between life events/parenting style and mental disorders among children and adolescents based on a large sample size in China. Therefore, in the present study, a cross-sectional study was carried out to assess the association of life events and parenting style with mental health.

Materials and methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was performed in 2015. The included sample was from one of the parts of the second stage for the first national survey of the prevalence of mental disorders for school students aged 6-16 in China4. For the children and adolescents with mental disorders included in this present study, the sample was from one of the five selected locations (i.e., Sichuan, Hunan, and Beijing). To compare the differences between the group with and without mental disorders, the ‘Positive group’ and ‘Negative group’ were defined. The Positive group means the included participants have at least one kind of mental disorder (CBCL ≥ 35), while the Negative group means they have no mental disorders (CBCL < 35).

This study was carried out following the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University. The Ethics Committee approved the protocol of the Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University. All of the children and adolescents and their parents provided written informed consent before data collection. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Psychiatric assessments were used to identify the positive group and negative group. A questionnaire screening the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was performed to identify students with behavioral and emotional problems by their parents’ reports. After that, the Adolescent Self-Rating Life Events Check List (ASLEC) and Egna Minnen Beträffande Uppfostran (EMBU) were used to assess the life events and the information for the parenting style. First, the CBCL, a questionnaire screening for behavioral problems, was conducted by caregivers. Participants with total scores above 35 were identified as high-risk individuals with mental disorders. Second, detailed psychiatric assessments, including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) interview, were performed in high-risk individuals. For the detailed diagnosis process of mental disorders, please see our previous publication4.

Measures

CBCL

The CBCL has been widely used for the screening of emotional and behavioral disorders29. The CBCL was completed by the caregivers (including parents) for a given child or adolescent. It was developed to assess a constellation of problem behaviors and comprises eight subscales, including withdrawn, somatic complaints, anxious/depressed, rule-breaking behavior, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, and aggressive behavior. The CBCL was seen as an excellent instrument to identify behavioral problems5,30,31. A higher score indicated more severe behavioral problems than lower scores.

MINI-KID

The MINI-KID is a brevity and low administration cost tool that is essentially a diagnostic tree formed by routed questions. It generates reliable and valid psychiatric diagnoses for psychometric evaluation in Chinese children and adolescents. In our study, 10 psychiatrists with attending physician titles or above were trained to perform the MINI-KID assessment.

ASLEC

The ASLEC is a scale composed of 27 items in six dimensions32: interpersonal relationships (the events reflected interpersonal conflict or contradiction), study pressure (mainly describe the stress caused by learning), being punished (life events that were punished by their caregivers, teachers or peers), bereavement (events of the death of beloved ones), health adaptation, and other dimensions (i.e., school refusal). The scale can assess the frequency and intensity of life events that participants experienced in the past half-year. The respondents rated each negative life event’s impact on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = extremely severe). The higher score showed that badly stressful life events were perceived. Previous studies found that this scale is reliable and valid among Chinese children33,34.

EMBU

The EMBU was compiled by C. Perris et al. in 198035. The Chinese version of EMBU was revised in 1993 by Yue Dongmei and others from China Medical University36. It is a convenient and reliable instrument for the assessment of parental attitudes and behaviors. The EMBU scale has 66 items. There are 58 items in 6 dimensions of the father’s parenting style subscale and 57 items in 5 dimensions of the mother’s parenting style subscale. The items are scored on a four-point Likert scale (1 = never to 4 = always). The dimensions of EMBU included emotional warmth (affection or love from parents), severe punishment (the act or speech of punishing of father or mother to the child), excessive interference (the parental act of hindering or obstructing or impeding unnecessary for children), preference (mother or father grant of favor to one child more than other sisters and brothers), rejection (rejecting from father or mother), and overprotection (providing excessive help or support from mother or father to their children).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were adopted in the course of analysis by IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0. First, sample distributions of sex, age, and the only child were described. Second, we calculated the scores of total problems of the CBCL; total score of ASLEC and its six dimensions; six dimensions of father and five dimensions of maternal parenting style. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the distribution of these assessment scores. If the distribution of these variables was nonnormal, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. Third, multivariate linear regression models were performed in both the positive group and negative group to identify the risk factors for life events and parenting styles associated with emotional and behavioral problems. Finally, binary logistic regression will be performed to identify the risk factors for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Statistical significance was based on two-tailed tests with 0.05 as the significance level.

In addition, for the selection bias, in stage 1, sampling weights of their provincial region, prefectural division, county/district, school, and class were included. In Stage 2, the weights of randomly picked participants with negative CBCL screening results were multiplied by the reciprocal of their sampling probabilities. Poststratification weight was calculated by age (6–11 years and 12–16 years) and sex (boys and girls). Individuals who refused to participate and did not complete all the assessments were treated as nonrespondents.

Result

The basic information of the negative group and positive group

A total of 20275 participants were included to identify children and adolescents with mental disorders. According to the first inclusion criteria of the positive group (CBCL ≥ 35) and negative group (CBCL < 35), a total of 3576 participants were identified in the positive group, while 3576 participants were selected randomly from the whole sample. A total of 41 participants were excluded due to not meeting the criteria of DSM-IV and not completing all the assessments in the Positive group, while a total of 15 participants were excluded due to not completing all the assessments in the Negative group. Finally, a total of 3535 participants were identified in the Positive group and 3561 in the Negative group. For more details, see Figs. 1 and 2.

The mean (standard deviation) age was 11.57 (3.03) years in the Positive group, while it was 11.9 (2.95) years. A total of 2035 males (57.57%) were included in the positive group, and 2271 males (63.77%) were included in the negative group. A total of 2043 (57.79%) were the only children in the positive group, and 2110 (59.25%) were the only children in the negative group.

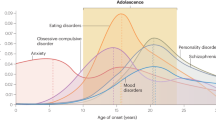

The CBCL score in the positive group

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to evaluate the distributions of CBCL total scores. The results showed that the CBCL total scores were nonnormally distributed (p < 0.001) (more details can be seen in sTable 1 in the Supplemental Materials). Therefore, we used the Mann–Whitney tests to compare the differences between sex (boys and girls) and the Only child (the Only child or not). We observed a significant difference between males and females in CBCL total scores (Z = −5.40, p < 0.001) (see Fig. 1). However, we observed no differences between the only child and the nononly child groups in CBCL total scores (Z = −1.05, p = 0.30). The total CBCL scores increased with age. A small peak appears at 7-8 years old, and the highest peak appears at 12-13 years old. More details can be seen in sFigure 1.

Multivariate linear regression in both the positive group and negative group

The multivariate linear regression analyses (method: Enter) (the total scores of CBCL were the dependent variable, and the dimensions of ASLEC and EMBU were the independent variables) showed that the dimension of punishment (B = 0.73, p = 0.01) and other (B = −0.60, p = 0.04) in ASLEC scale can significantly predict CBCL total scores in the Positive group. However, in the negative group, excessive interference in fathers (B = −0.85, p = 0.02) and mothers (B = −1.25, p = 0.03) significantly predicted CBCL total scores in the negative group. For more details, see Table 1.

Binary logistic regression (to identify the risk factors for mental disorders)

To identify the risk factors for mental disorders, binary logistic regression (forward stepwise) was performed (the dependent variable was whether the participant had a mental disorder: yes, had a mental disorder, positive group; no, had no mental disorders, negative group). The independent variables included the dimensions of ASLEC and EMBU, age, sex and only child. We found that sex, age and overprotection from the father were risk factors (p < 0.001). For more details, see Table 2.

Discussion

The present study investigates the relationships among school students’ life events, parenting style, and mental health in China based on a large sample size. In this study, we found a higher CBCL total score in males than females. In the children and adolescents with a mental disorder, we found that mental health problems increased with age, and the highest peak of CBCL was at 12–13 years old. In the positive group, being a punished factor in ASLEC can predict the total scores of CBCL. Moreover, we found that overprotection from fathers was an important risk factor for mental disorders.

According to the multiple linear regression analysis, being a punished factor in the life event scale can predict the total scores of the CBCL. To the best of our knowledge, family conflict, expected selected failure, criticism, fighting, and being beaten by parents are common life events of punishment. Under the traditional Chinese education system, teachers and parents may be the main perpetrators of punishment37. Many parents or teachers think that punishment can make children more obedient38, which might follow the cultural tradition of “spare the rod and spoil the child.” However, according to the study results, this approach may be harmful to children and adolescents’ mental health. When the child is punished, negative emotions may appear. Studies show that punishment can lead to depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms39,40. Children who suffer punishment have higher levels of violence or self-harm41,42. This phenomenon was also confirmed by neuroscience studies43,44,45. For example, after training on the force-tracking task, participants trained with punishment showed increased premotor cortex connectivity with the ventral striatum45. Given the importance of these domains in emotion control, it is not surprising that punishment leads to mental problems. For families, punishment is usually associated with parenting style. Family disharmony, improper parenting, and poor parent–child relationships may lead to behavioral and psychological risks46,47. In addition, teachers’ criticism and corporal punishment are also important, influential factors. Teachers’ punishment also needs to be vigilant, affecting students’ academic performance and mental health48.

Against the background of Chinese culture, punishment seems to be inevitable in the experiences of children’s growth49. However, we call for the adoption of scientific education to minimize the occurrence of punishment. This action may increase public awareness, especially among parents and teachers, about the occurrence and importance of mental health problems in children and adolescents. Therefore, psychological prevention and education programs should be performed to avoid the serious negative effects of punishment. For schools, it is very important to create a good learning atmosphere and a harmonious teacher-student relationship. For every family, investing time in parenting and raising parent–child relationships are necessary. Parents can develop a democratic and “soft” way to deal with children’s “faults” instead of scolding or punishing them.

In the present study, we found that overprotection from the father is an important risk factor for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Overprotection is a parenting style that will let children lack the opportunity for frustration education. Paternal overprotection may be characterized by removing children from potentially threatening situations and providing excessive help during challenging tasks50. A previous study implicated that overprotection of parents might aid the development of anxiety in their children51. Our results found that children and adolescents with mental disorders are more likely to be overprotected by their fathers. However, Xu et al.50 found that social anxiety for adolescents in migrant families is positively correlated with parental overprotection, especially from the mother. Taken together, these results indicated that paternal overprotection may have a negative impact on mental health for children and adolescents. It should be noted that fathers are less likely to be the primary caregivers, and spending time with their children may increase mothers’ parenting stress. In traditional Chinese culture, women are conditioned to do housework and look after children, while men have to make money and support their families. It seemed that fathers did not have enough time and energy to take care of their children, which may lead to the father-child relationship not being “strong.” When fathers participate in the process of child-rearing, they may show overprotection for their children, who use this way to “make up for their fault” of not being able to accompany their children for more time. Overprotection may lead to children’s lack of experience and skills in dealing with life events. This might be the reason why overprotection from the father might develop to be the ‘risk’ factor.

In addition, the CBCL has been widely used for screening emotional and behavioral problems4. To the best of our knowledge, a higher total CBCL score suggests more serious emotional and behavioral problems29,30. In the present study, we identify a small peak that appears at 7-8 years old and the highest peak at 12-13 years old. In China, 7 years old is the first grade of primary school, while approximately 12-13 years old is the first grade of junior middle school. When students face a new school environment, they may be more likely to have mental health problems52. Therefore, we need to pay more attention to children’s mental health in these two critical periods and carry out the necessary screening.

Based on the results of this study, several issues for the development of mental health for children and adolencents need to be addressed in future studies. First, the mental healthcare system should gradually improve to address the urgent mental health requirements of children. In this study, a total of 20275 children and adolescents participated in Stage 1. After screening by CBCL, MINI-KID and DSM-IV, 3535 participants were diagnosed with at least one kind of mental disorder (17.43%). One of the possible reasons for the high prevalence of mental disorders might be the urgent need for the development of the mental healthcare system for children in China53. Second, mental health screening for children and adolescents should be carried out in a timely manner. In this study, we found that mental health problems increased with age. The highest peak of CBCL was at 12-13 years old, and a small peak also emerged at 6-7 years old. These two key age points might need further attention during mental health screening. Potential risk factors are also an important part of mental health screening, especially life events and parent style. Third, the awareness of mental health for parents training needs to be further encouraged. For example, how to improve the parent style and reduce life events and how to identify the early symptoms associated with mental health. Additionally, in this study, the CBCL was used as the screening tool to identify participants with mental disorders. The CBCL is a useful and validated tool for early screening for children and adolescents54. We can also use the eight factors of the CBCL to present the defined behavioral and emotional features for different mental disorders in children and adolescents.

Limitations

First, our inclusion and exclusion criteria did not consider the family history of mental illness, left behind families, single families, or other factors, which may cause bias to the results. Second, our data come from specific regions. Due to different economic and social development levels and cultural customs, other cities in China may have different results, so the results cannot be further promoted. Third, selection bias is the bias introduced by the selection of data for analysis such that proper randomization is not achieved, thereby ensuring that the sample obtained is not representative of the population intended to be analyzed55. Although we have assessed the selection bias in several dimensions, senior three school students who prepare for the College Entrance Examination and children and adolescents who dropped out of school were not included in our sample. Furthermore, some sociodemographic factors were not included, such as parents’ education background and family income level. We should address these issues in future studies to reduce selection bias.

Conclusions

A proportion of life events and parenting styles are important to the mental health of children and adolescents. Among them, being punished and overprotection from the father were two important factors associated with the mental health of children and adolescents in China. Parents should adopt a democratic approach based on encouragement rather than punishment. More participation of fathers in children’s upbringing will be needed while avoiding overprotection.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Merrick, M. T. et al. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abus. Negl. 69, 10–19 (2017).

Wu, J. L. & Pan, J. The scarcity of child psychiatrists in China. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 286–287 (2019).

Zheng, Y. & Zheng, X. Current state and recent developments of child psychiatry in China. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 9, 10 (2015).

Cui, Y. et al. The prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese school children and adolescents aged 6–16: a national survey. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 30, 233–241 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Emotional and behavioral problems, social competence and risk factors in 6-16-year-old students in Beijing, China. PLoS ONE 14, e0223970 (2019).

Lin, W. & Ge, L. Research status of social psychological factors of mental disorders. Chin. J. Public Health 2, 130–131 (2006). (in Chinese).

O’Reilly, M., Svirydzenka, N., Adams, S. & Dogra, N. Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 53, 647–662 (2018).

Tang, X., Tang, S., Ren, Z. & Wong, D. F. K. Psychosocial risk factors associated with depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary schools in mainland china: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 263, 155–165 (2020).

Zhou, L., Fan, J. & Du, Y. Cross-sectional study on the relationship between life events and mental health of secondary school students in Shanghai, China. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 24, 162–171 (2012).

Guang, Y. et al. Depressive symptoms and negative life events: What psycho-social factors protect or harm left-behind children in China? BMC Psychiatry 17, 402 (2017).

Ying, L. et al. Parent-child communication and self-esteem mediate the relationship between interparental conflict and children’s depressive symptoms. Child Care Health Dev. 44, 908–915 (2018).

Kyu, H. H. et al. Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: findings from the global burden of disease 2013 study. JAMA Pediatr. 170, 267–287 (2016).

Collett-Solberg, P. F. et al. Diagnosis, genetics, and therapy of short stature in children: a growth hormone research society international perspective. Horm. Res Paediatr. 92, 1–14 (2019).

Zhong, B. L. et al. Depressive disorders among children in the transforming China: an epidemiological survey of prevalence, correlates, and service use. Depress Anxiety 30, 881–892 (2013).

Patel, V. et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 392, 1553–1598 (2018).

Gao, F. et al. The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem between negative life events and positive social adjustment among left-behind adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 19, 239 (2019).

Ji, S. & Wang, H. A study of the relationship between adverse childhood experiences, life events, and executive function among college students in China. Psicol. Reflex Crit. 31, 28 (2018).

Salleh, M. R. Life event, stress and illness. Malays. J. Med Sci. 15, 9–18 (2008).

Tosevski, D. L. & Milovancevic, M. P. Stressful life events and physical health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 19, 184–189 (2006).

Mulder, S. & de Rooy, D. Pilot mental health, negative life events, and improving safety with peer support and a just culture. Aerosp. Med Hum. Perform. 89, 41–51 (2018).

Rodway, C., Tham, S. G., Turnbull, P., Kapur, N. & Appleby, L. Suicide in children and young people: can it happen without warning? J. Affect Disord. 275, 307–310 (2020).

Xiuhong, X. & Shuqiao, Y. Validity and reliability of the adolescent self-rating life events checklist in middle school students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 29, 355–360 (2015).

Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F. & Fraleigh, M. J. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Dev. 58, 1244–1257 (1987).

Fei, Y. & Xinde, W. The relationship among parenting style, parent-adolescent conflict and depression/anxiety of junior high school girls. China J. Health Psychol. 22, 1418–1420 (2014).

Sellers, R. et al. Examining the role of genetic risk and longitudinal transmission processes underlying maternal parenting and psychopathology and children’s ADHD symptoms and aggression: utilizing the advantages of a prospective adoption design. Behav. Genet 50, 247–262 (2020).

Kendler, K. S., Ohlsson, H., Sundquist, J., Sundquist, K. & Edwards, A. C. The sources of parent-child transmission of risk for suicide attempt and deaths by suicide in Swedish national samples. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 928–935 (2020).

Huang, C. Y. & Hsieh, Y. P. Relationships between parent-reported parenting, child-perceived parenting, and children’s mental health in Taiwanese children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16, 1049 (2019).

Yangzong, C. et al. Validity and reliability of the Tibetan version of s-EMBU for measuring parenting styles. Psychol. Res Behav. Manag 10, 1–8 (2017).

Reed, M. L. & Edelbrock, C. Reliability and validity of the direct observation form of the child behavior checklist. J. Abnorm Child Psychol. 11, 521–530 (1983).

Leung, P. W. et al. Test-retest reliability and criterion validity of the Chinese version of CBCL, TRF, and YSR. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 47, 970–973 (2006).

Weine, A. M., Phillips, J. S. & Achenbach, T. M. Behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese and American children: parent and teacher reports for ages 6 to 13. J. Abnorm Child Psychol. 23, 619–639 (1995).

Liu, X. C., Oda, S., Peng, X. & Asai, K. Life events and anxiety in Chinese medical students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 32, 63–67 (1997).

Liu, C., Zhao, Y., Tian, X., Zou, G. & Li, P. Negative life events and school adjustment among Chinese nursing students: the mediating role of psychological capital. Nurse Educ. Today 35, 754–759 (2015).

Liu, X. et al. Life events, locus of control, and behavioral problems among Chinese adolescents. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 1565–1577 (2000).

Perris, C., Jacobsson, L., Lindström, H., von Knorring, L. & Perris, H. Development of a new inventory assessing memories of parental rearing behaviour. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 61, 265–274 (1980).

Dongmei, Y. Parenting style: preliminary revision of EMBU and application of in neurosis. Chinese Mental Health J. 7, 97–101. (1993).

Chang, L., Dong, M., Yu, R., Sun, C. & Zeng, L. [Current status and associated risk factors of child abuse on children aged 7-12 in rural areas of Ningxia]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 35, 913–916 (2014).

Wang, M. & Liu, L. Reciprocal relations between harsh discipline and children’s externalizing behavior in China: a 5-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 89, 174–187 (2018).

Cao, Y. P. et al. [An epidemiological study on domestic violence in Hunan, China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing. Xue Za Zhi 27, 200–203 (2006).

Zhou, Y., Liang, Y., Cheng, J., Zheng, H. & Liu, Z. Child maltreatment in Western China: demographic differences and associations with mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16, 3619 (2019).

Afifi, T. O., Mota, N. P., Dasiewicz, P., MacMillan, H. L. & Sareen, J. Physical punishment and mental disorders: results from a nationally representative US sample. Pediatrics 130, 184–192 (2012).

Nkuba, M., Hermenau, K., Goessmann, K. & Hecker, T. Mental health problems and their association to violence and maltreatment in a nationally representative sample of Tanzanian secondary school students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 53, 699–707 (2018).

Riesel, A., Kathmann, N., Wüllhorst, V., Banica, I. & Weinberg, A. Punishment has a persistent effect on error-related brain activity in highly anxious individuals twenty-four hours after conditioning. Int J. Psychophysiol. 146, 63–72 (2019).

Yuan, Y. et al. Reward inhibits paraventricular CRH neurons to relieve stress. Curr. Biol. 29, 1243–1251 (2019). e1244.

Steel, A., Silson, E. H., Stagg, C. J. & Baker, C. I. Differential impact of reward and punishment on functional connectivity after skill learning. Neuroimage 189, 95–105 (2019).

Eun, J. D., Paksarian, D., He, J. P. & Merikangas, K. R. Parenting style and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 53, 11–20 (2018).

Liu, Y. N. et al. [Effect of family environment in childhood and adolescence on mental health in adulthood]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing. Xue Za Zhi 39, 600–603 (2018).

Han, Z., Fu, M., Liu, C. & Guo, J. Bullying and suicidality in urban Chinese youth: the role of teacher-student relationships. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 21, 287–293 (2018).

Han, Z., Zhang, G., Zhang, H. School bullying in urban China: prevalence and correlation with school climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14, 1116 (2017).

Xu, J., Ni, S., Ran, M. & Zhang, C. The relationship between parenting styles and adolescents’ social anxiety in migrant families: a study in Guangdong, China. Front Psychol. 8, 626 (2017).

Rork, K. E. & Morris, T. L. Influence of parenting factors on childhood social anxiety: direct observation of parental warmth and control. Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 31, 220–235 (2009).

Erskine, H. E. et al. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 26, 395–402 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Building the mental health management system for children post COVID-19 pandemic: an urgent focus in China. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01763-0 (2021).

Biederman, J. et al. Can the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) help characterize the types of psychopathologic conditions driving child psychiatry referrals? Scand. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Psychol. 8, 157–165 (2020).

Tripepi, G., Jager, K. J., Dekker, F. W. & Zoccali, C. Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin. Pr. 115, c94–c99 (2010).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82001445) and the National Key Technology R&D Program of China (No. 2012BAI01B02). Capital Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

For this manuscript, YC and YL (Ying Li) took the initiative in conception and design, and YL (Yanlin Li) analyzed the data and finished the draft. JC, FW (Feng Wen), LY, JY, FW (Fang Wang), JL gathered the data and gave good suggestions for this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

This study was carried out following the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University. The Ethics Committee approved the protocol of the Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University. All of the children and adolescents and their parents provided written informed consent before data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chu, J., Wen, F. et al. Life events and parent style for mental health in children: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr Res 93, 1432–1438 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02209-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02209-2