Abstract

Objective

To examine changes in prenatal opioid prescription exposure following new guidelines and policies.

Study design

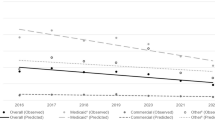

Cohort study of all (262,284) Wisconsin Medicaid-insured live births 2010–2019. Prenatal exposures were classified as analgesic, short term, and chronic (90+ days), and medications used to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD). We describe overall and stratified temporal trends and used linear probability models with interaction terms to test their significance.

Result

We found 42,437 (16.2%) infants with prenatal exposure; most (90.5%) reflected analgesic opioids. From 2010 to 2019, overall exposure declined 12.8 percentage points (95% CI = 12.1–13.1). Reductions were observed across maternal demographic groups and in both rural and urban settings, though the extent varied. There was a small reduction in chronic analgesic exposure and a concurrent increase in MOUD.

Conclusion

Broad and sustained declines in prenatal prescription opioid exposure occurred over the decade, with little change in the percentage of infants chronically exposed.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used in this study are proprietary administrative data owned by the State of Wisconsin Department of Children and Families and Department of Health Services. They were made available to the authors for this research under data use agreements between each agency and the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Wisconsin state law prohibits sharing these data or making them publicly available.

References

Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rathmell JP, Seeger JD, Doherty M, Fischer MA, et al. Patterns of opioid utilization in pregnancy in a large cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries in the United States. Anesthesiol. 2014;120:1216–24.

Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997–1002.

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1487–92.

Maclean JC, Witman A, Durrance CP, Atkins DN, Meinhofer A. Prenatal substance use policies and infant maltreatment reports: study examines prenatal substance use policies and infant maltreatment reports. Health Aff. 2022;41:703–12.

Pac J, Durrance C, Berger L, Ehrenthal DB. The effects of opioid use during pregnancy on infant health and well-being. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2022;703:106–38.

Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000–2009. JAMA. 2012;307:1934–40.

Prindle JJ, Hammond I, Putnam-Hornstein E. Prenatal substance exposure diagnosed at birth and infant involvement with child protective services. Child Abus Negl. 2018;76:75–83.

Rebbe R, Mienko JA, Brown E, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Hospital variation in child protection reports of substance exposed infants. J Pediatr. 2019;208:141–7.e2.

Rebbe R, Mienko JA, Brown E, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Child protection reports and removals of infants diagnosed with prenatal substance exposure. Child Abus Negl. 2019;88:28–36.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–45.

Dude C, Jamieson DJ. Assessment of the safety of common medications used during pregnancy. JAMA. 2021;326:2421–2.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1070–6.

Straub L, Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Zhu Y, Vine S, Desai RJ, et al. Chronic prescription opioid use in pregnancy in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:504–13.

Haegerich TM, Jones CM, Cote PO, Robinson A, Ross L. Evidence for state, community and systems-level prevention strategies to address the opioid crisis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107563.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e81–94.

Andrilla CHA, Moore TE, Patterson DG, Larson EH. Geographic distribution of providers with a DEA waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a 5‐year update. J Rural Health. 2019;35:108–12.

Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Jeng PJ, Bao Y. Prescription drug monitoring program mandates: impact on opioid prescribing and related hospital use. Health Aff. 2019;38:1550–6.

Austin AE, Bona VD, Cox ME, Proescholdbell S, Fliss MD, Naumann RB. Prenatal use of medication for opioid use disorder and other prescription opioids in cases of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome: North Carolina Medicaid, 2016–2018. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:1682–5.

Nechuta S, Mukhopadhyay S, Golladay M, Rainey J, Krishnaswami S. Trends, patterns, and maternal characteristics of opioid prescribing during pregnancy in a large population-based cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;233:109331.

Renny MH, Yin HS, Jent V, Hadland SE, Cerdá M. Temporal trends in opioid prescribing practices in children, adolescents, and younger adults in the US from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1043–52.

Schieber LZ, Guy GP, Seth P, Young R, Mattson CL, Mikosz CA, et al. Trends and patterns of geographic variation in opioid prescribing practices by state, United States, 2006-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e190665.

Hirai AH, Ko JY, Owens PL, Stocks C, Patrick SW. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid-related diagnoses in the US, 2010–2017. JAMA. 2021;325:146–55.

Wang Y, Berger L, Durrance C, Kirby RS, Kuo D, Pac J, et al. Duration and timing of in utero opioid exposure and incidence of neonatal withdrawal syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142:603–11.

Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization—United States, 1999–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845.

Brown PR, Thornton K. Technical report on lessons learned in the development of the institute for research on poverty’s Wisconsin administrative data core. 2020. https://www.irp.wisc.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/TechnicalReport_DataCoreLessons2020.pdf

Dietz PM, Bombard JM, Hutchings YL, Gauthier JP, Gambatese MA, Ko JY, et al. Validation of obstetric estimate of gestational age on US birth certificates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:335.e1–e5.

Martin JA, Osterman MJ, Kirmeyer SE, Gregory EC. Measuring gestational age in vital statistics data: transitioning to the obstetric estimate. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1–20.

Basco WT, McCauley JL, Zhang J, Mauldin PD, Simpson KN, Heidari K, et al. Trends in dispensed opioid analgesic prescriptions to children in South Carolina: 2010–2017. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e20200649.

Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. National, Statistics CfH. Hyattsville, MD; 2014.

Sujan AC, Rickert ME, Quinn PD, Ludema C, Wiggs KK, Larsson H, et al. A population-based study of concurrent prescriptions of opioid analgesic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications during pregnancy and risk for adverse birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2021;35:184–93.

Krans EE, Patrick SW. Opioid use disorder in pregnancy: health policy and practice in the midst of an epidemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:4.

Ko JY, Tong VT, Haight SC, Terplan M, Snead C, Schulkin J. Obstetrician–gynecologists’ practice patterns related to opioid use during pregnancy and postpartum—United States, 2017. J Perinatol. 2020;40:412–21.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wisconsin Department of Health Services for the use of data for this research but acknowledge that these agencies do not certify the accuracy of the analyses presented. We are grateful for excellent data access and programming assistance provided by HeeJin Kim, Hsiang-Hui (Daphne) Kuo, Krista Bryz-Gornia, Steven Cook, Dan Ross, and Lynn Wimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Funding

This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant #R01HD102125 (MPI Ehrenthal and Berger), with additional support from the Social Science Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University and the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors meet all four criteria for authorship and have approved the manuscript. DE: Conceived of and designed the work; co-led data acquisition; contributed to the interpretation of data; drafted, edited, and approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for the work. YW: Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; conducted the analysis; contributed to the interpretation of data; edited and approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for the work. JP: Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; contributed to the interpretation of data; edited and approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for the work. CD: Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; contributed to the interpretation of data; edited and approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for the work. RK: Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; contributed to the interpretation of data; edited and approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for the work. LB: Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; co-led the acquisition of data; contributed to the interpretation of data; edited and approved the final manuscript; and agrees to be accountable for the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Boards and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ehrenthal, D.B., Wang, Y., Pac, J. et al. Trends in prenatal prescription opioid use among Medicaid beneficiaries in Wisconsin, 2010–2019. J Perinatol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-01954-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-01954-y