Abstract

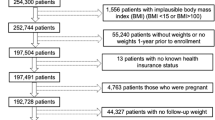

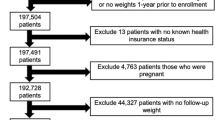

This study examined whether the neighborhood built environment moderated gestational weight gain (GWG) in LIFE-Moms clinical trials. Participants were 790 pregnant women (13.9 weeks’ gestation) with overweight or obesity randomized within four clinical centers to standard care or lifestyle intervention to reduce GWG. Geographic information system (GIS) was used to map the neighborhood built environment. The intervention relative to standard care significantly reduced GWG (coefficient = 0.05; p = 0.005) and this effect remained significant (p < 0.03) after adjusting for built environment variables. An interaction was observed for presence of fast food restaurants (coefficient = −0.007; p = 0.003). Post hoc tests based on a median split showed that the intervention relative to standard care reduced GWG in participants living in neighborhoods with lower fast food density 0.08 [95% CI, 0.03,0.12] kg/week (p = 0.001) but not in those living in areas with higher fast food density (0.02 [−0.04, 0.08] kg/week; p = 0.55). Interaction effects suggested less intervention efficacy among women living in neighborhoods with more grocery/convenience stores (coefficient = −0.005; p = 0.0001), more walkability (coefficient −0.012; p = 0.007) and less crime (coefficient = 0.001; p = 0.007), but post-hoc tests were not significant. No intervention x environment interaction effects were observed for total number of eating establishments or tree canopy. Lifestyle interventions during pregnancy were effective across diverse physical environments. Living in environments with easy access to fast food restaurants may limit efficacy of prenatal lifestyle interventions, but future research is needed to replicate these findings.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, Glonti K, Oppert JM, Charreire H, et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:233.

Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999;29:563–70.

Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obes Res. 2003;11:23S–43S.

French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:309–35.

Kerr J, Norman GJ, Adams MA, Ryan S, Frank L, Sallis JF, et al. Do neighborhood environments moderate the effect of physical activity lifestyle interventions in adults? Health Place. 2010;16:903–8.

Jilcott Pitts SB, Keyserling TC, Johnston LF, Evenson KR, McGuirt JT, Gizlice Z, et al. Examining the association between intervention-related changes in diet, physical activity, and weight as moderated by the food and physical activity environments among Rural, Southern Adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1618–27.

Headen I, Laraia B, Coleman-Phox K, Vieten C, Adler N, Epel E. Neighborhood typology and cardiometabolic pregnancy outcomes in the maternal adiposity metabolism and stress study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27:166–73.

Kirkegaard H, Stovring H, Rasmussen KM, Abrams B, Sorensen TI, Nohr EA. How do pregnancy-related weight changes and breastfeeding relate to maternal weight and BMI-adjusted waist circumference 7 y after delivery? Results from a path analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:312–9.

Mamun AA, Kinarivala M, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM, Callaway LK. Associations of excess weight gain during pregnancy with long-term maternal overweight and obesity: evidence from 21 y postpartum follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1336–41.

Peaceman AM, Clifton RG, Phelan S, Gallagher D, Evans M, Redman LM, et al. Lifestyle interventions limit gestational weight gain in women with overweight or obesity: a prospective meta-analysis. Obesity. 2018;0:1–9.

Clifton RG, Evans M, Cahill AG, Franks PW, Gallagher D, Phelan S, et al. Design of lifestyle intervention trials to prevent excessive gestational weight gain in women with overweight or obesity. Obesity. 2016;24:305–13.

James P, Berrigan D, Hart JE, Hipp JA, Hoehner CM, Kerr J, et al. Effects of buffer size and shape on associations between the built environment and energy balance. Health Place. 2014;27:162–70.

Drewnowski A, Buszkiewicz J, Aggarwal A, Rose C, Gupta S, Bradshaw A. Obesity and the built environment: a reappraisal. Obesity. 2020;28:22–30.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health through The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, U01 DK094418, U01 DK094463, U01 DK094416, 5U01 DK094466 (RCU)), The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI, U01 HL114344, U01 HL114377), and The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, U01 HD072834). In addition, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), the NIH Office of Research in Women’s Health (ORWH), the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (OBSSR), the NIH Office of Disease Prevention (ODP), the Indian Health Service, the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK, and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD) contributed support. Additional support was received from the NIDDK Obesity Nutrition Research Centers (P30 DK026687, P30 DK072476, P30 DK56341), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards (U54 GM104940, U54 MD007587, UL1 RR024992), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (S21MD001830) and EXODIAB-Excellence of diabetes research in Sweden. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Russel White at the Cal Poly Robert E. Kennedy Library for his invaluable input and technical assistance in compiling the GIS data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors’ work has been funded by the NIH. Author SP has received compensation from WW, outside the submitted work. LMR’s SmartMoms™ smartphone application evaluated in the trial at Pennington Biomedical Research Center has a pending trademark and is available for licensure. No other potential competing interests were reported. SP reports receiving a grant from WW unrelated to this work. LMR and CKM reported one of the interventions evaluated in the Expecting Success trial at Pennington Biomedical Research Center (the SmartMoms™ smartphone application) is a licensed trademark and is available for licensure.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the LIFE-Moms consortium and their affiliations are listed in Supplementary Information.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phelan, S., Marquez, F., Redman, L.M. et al. The moderating role of the built environment in prenatal lifestyle interventions. Int J Obes 45, 1357–1361 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00782-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00782-w

This article is cited by

-

Impact of the Neighborhood Food Environment on Dietary Intake and Obesity: a Review of the Recent Literature

Current Diabetes Reports (2023)

-

The Prenatal Neighborhood Environment and Geographic Hotspots of Infants with At-risk Birthweights in New York City

Journal of Urban Health (2022)