Abstract

Meaningful child participation in medical research is seen as important. In order to facilitate further development of participatory research, we performed a systematic literature study to describe and assess the available knowledge on participatory methods in pediatric research. A search was executed in five databases: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Cochrane. After careful screening of relevant papers, finally 24 documents were included in our analysis. Literature on participatory methods in pediatric research appears generally to be descriptive, whereby high-quality evidence is lacking. Overall, five groups of participatory methods for children could be distinguished: observational, verbal, written, visual, and active methods. The choice for one of these methods should be based on the child’s age, on social and demographic characteristics, and on the research objectives. To date, these methods are still solely used for obtaining data, yet they are suitable for conducting meaningful participation. This may result in a successful partnership between children and researchers. Researchers conducting participatory research with children can use this systematic review in order to weigh the current knowledge about the participatory methods presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In 1989, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child promoted the right of the child to be listened to (1,2,3). Since then, the active participation of children and young people in research has increased, mainly in social science studies. Medical research seems to lag behind, which is wondering, because proper use could be very promising. In participatory pediatric research, children should be actively involved in defining relevant research questions and in the design and conduct of studies (4). In adults, participatory research has proven to have impact on all key stages of the research process; however, more and stronger evidence is needed (5).

To our knowledge, an overview and assessment of available participatory methods for children in medical research is currently lacking. Aims and benefits (6), and several participatory methods for children have been described; however, evidence regarding the effects of using different participatory methods is not presented. This hampers the proper use of different participatory methods for two reasons. First, researchers are reinventing the wheel themselves every time they look for ways to involve children in research. Second, using unsuitable participatory methods may even have negative effects on the participants or the quality of the research (3). In order to facilitate further development of participatory research with children, we performed a systematic literature study to describe and evaluate the available knowledge on participatory methods in pediatric research.

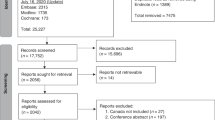

An extensive search was drafted, with search terms covering many synonyms, e.g., participation, engagement, involvement, partnership. The search was executed in PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Cochrane databases on 3 December 2014 ( Figure 1 ). Titles were screened, abstracts and full text were read, and hand search was carried out on bibliographies of included papers. Selection was discussed among the authors. Inclusion criteria were pediatric medical research and active involvement of children in the design and conduct of the study. Moreover, the articles must contain at least a description of the participatory method used.

Selection of studies.

Data about aims, benefits, and risks as well as data about the different groups of participatory research methods was extracted systematically. Participatory pediatric research was defined as research which actively involves children in defining relevant research questions and in the design and conduct of studies. Participatory methods were defined as any method that can be used to obtain children’s views, aiming to involve them in the design and conduct of research. Persons under the age of 6 y were defined as “pre-school children,” persons from 6 to 12 y were defined as “school aged children,” and persons from 12 to 18 y were defined as “young people.” “Children” was used for all persons under 18 y. Participatory research involving parents was not included, since this research is solely focused on methods involving children. Risk of bias was not systematically assessed, since data is generally lacking. The PRISMA checklist was used for this review (7).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Centre Utrecht. Informed consent was not required for this study.

Search and Characteristics of Included Studies

Six hundred and forty-nine titles were screened, 232 abstracts and 47 full texts were read. Initially, 11 articles were included. Eight were reviews, one was a research proposal, and two were original research papers. Hand search of the bibliography of included papers resulted in the inclusion of three additional reviews, seven original research papers, one book chapter, and two guidelines ( Figure 1 ). The seven additional original research papers did not match the search criteria at first, because they describe obtaining data using specific participatory methods instead of describing participatory research in children. In total, 9 original research papers, 11 reviews, and 4 additional documents are included in this systematic review. Since relevant data appeared to be scarce, reviews of medical research as well as social science studies are knowingly included because of the additional information they provide. Characteristics of included original research papers ( Table 1 ) and of included reviews and other documents ( Table 2 ) are listed. Unfortunately, a systematic quality assessment was not helpful due to the relative lack of data. Quality of the data is discussed in the discussion section.

Nine original research papers using participatory methods in their pediatric research were identified. In these articles, the methods used are extensively described, as are the views and experiences of participating children and researchers. However, we found no comparative studies on participatory methods in pediatric research. Seven narrative reviews of child involvement in social sciences and four reviews of child participation in medical research were identified; one of these reviews is a systematic review. The reviews are predominantly focused on necessity of participatory research (8), ethics (3,9,10), risks and benefits (6), and practicalities such as inclusion or dissent (2,9,11,12,13) ( Table 2 ). None of the reviews extensively described participatory methods for pediatric medical research. The two guidelines give an overview of practical tips for child involvement in research, but their statements are solely based on expert’s opinions.

Aims, Benefits, and Risks of Participatory Research

In the social science and medical literature, a variety of aims and benefits of child participation is described. A general aim is to “bridge the gap between the world as it is lived and the world of scientific study and dispassionate explanation” (9,11). Other reported benefits are based on experiences of children and researchers: participatory research is a positive experience for both children and researchers (10). Benefits for the children are their increased empowerment (9), self-confidence, and self-esteem (6,10). Also knowing that their views and opinions are listened to and respected and that they can make a difference or help other children and in getting the opportunity to share frustrations and appreciations were reported as beneficial effects of participatory research (12). Finally, children are more likely to develop an on-going and effective dialogue with adults (2,6). As for the benefits for research, children’s involvement improves the level of understanding of researchers, it exposes views that had not been anticipated and adds richness, validity, and relevance to the research project (9,10).

Negative side effects of participation have also been reported. When participation is sought, but does not lead to any changes in policy or practice, or children and young people are not informed well, it can cause disillusion (3). This may even result in a lack of trust in general, which might have an impact on future collaboration in research and in medical care and treatment (12). Next to disillusion, there is also a risk of overburdening children, especially when it comes to remembering and reviving sensitive issues or situations. Learning about other’s lives and views may cause distress in children (12).

Participatory Methods

Five different groups of participatory methods are described in medical and social literature: observational, verbal, written, visual, and active methods (14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29).

Observational Methods

There are several observational methods, wherein the observer is just observing or can participate in the observed group and moreover can have an influence on the shape of events, interactions, feelings, attitudes, and behaviour. The observer may be a child participating in the research team. Children’s activities and behaviour are observed and recorded (14,15).

Observation is used to generate research questions, to verify information gained with other methods, or to generate insights which can be tested with other methods. Observation is useful for obtaining information about natural behaviours and is mostly used in preschool children. Observational methods are described as participatory methods, although often there is no interaction with the children themselves (14,15).

Verbal Methods

A variety of verbal methods is described. The two main options for using verbal methods are individual interviews or focus group discussions. Both options can be performed with different tools to stimulate conversation (14,15). Verbal methods are mainly used in school-aged children and young people who are able to communicate well verbally, in order to obtain views, thoughts, and stories of children.

Interviews are common in medical research (16,17). The child is given the opportunity to speak for itself. It is important to record not just the words but also body language and tone of voice. Interviews should take place with children who are interested to talk about the topic. Ideally, a child initiates the interview itself, or children are interviewed by other children. It is recommended that interviews are not the first method used in participatory pediatric research, because children first need to gain confidence in themselves, in the researcher and in the research (14,15).

Focus group discussions are facilitated in-depth discussions in a group of children. These discussions encourage the individual and collective voice of children and can be very helpful in medical research (18,19,20), if conducted properly. Since focus group discussions can be very exciting for children, it is proposed that there should be a maximum of 4–6 school-aged children or 6–8 young people, with ages ranging 2–3 y maximal. It can help to recruit children in friendship pairs, to compose single-sex groups if necessary, to do warm-up and ice-breaking exercises as games, songs, and role plays and to plan re-energizers. Session length should be 60 min for school-aged children and 90 min for young people. As with interviews, the atmosphere should be open and informal, with first names, short questions, simple language, and no right or wrong answers (14,15,16,21). An important issue when children are asked to participate in focus group discussions is confidentiality, which cannot be assured when information is shared with other children. Children and their parents should be aware of this (12).

Written Methods

Most school-aged children and young people are used to exercises that include writing and many children enjoy writing. Children often find it helpful to write down what they feel when they are under stress or coping with difficult feelings. The most productive form of written methods is writing essays on specific topics (15). However, the most used form is the questionnaire. It can be used to evaluate services, to assess patient satisfaction, or to determine treatment outcomes (10). It is suggested that self-completion questionnaires and web-surveys should not be used under the age of 12 y, unless appropriate level of support is available because reliability may be questionable (14). It should also be ensured that children with learning difficulties are not negatively impacted by the method used. A more creative form of written methods is the draw and write method, which will be discussed in section about visual methods. Lastly, another frequently discussed method is keeping a diary. Children record thoughts in words or pictures over a period of time. This is said to be especially suitable if the gathered data is about sensitive issues or needs to be gathered on a daily basis. Diaries have been frequently used in pediatric research, but almost always by parents, not by children themselves (14).

Visual Methods

Visual methods exist in many different forms, one more participatory than another. It is suggested that these methods can be used in the early stages of research, for ice-breaking or for stimulating the use of other methods. Visual methods are fun, and they can help children in communicating thoughts and emotions they cannot tell or write down: “A picture paints a thousand words.” Children who find it difficult to convey their fears, feelings, and thoughts in words, especially when it comes to sensitive, embarrassing, or difficult issues, might find it easier to express them visually (22).

The most used form of visual communication is drawing, a fun and nonthreatening method (16,22,23). Even though most school-aged children are familiar with drawing, the method should not be used when children are not familiar with using pens or pencils or other equipment, or when they feel they are “not good” at art, or if there is no opportunity to explain the drawings to the researcher. Children’s own visual representations almost always require their own explanation by writing or talking about it, since it represents the child’s own understandings and realities. Drawing might also be less suitable for young people, who may find it childish (14). Next to individual drawing, a drawing, painting, or poster can be produced with a group, in order to encourage discussion about a particular topic. It stimulates the group to focus on the key issues (14).

A second form of using visual methods is a video diary. It can be used to gain insight into participant’s disease and treatment experiences (24,25) or experiences during study procedures. For most children, it is difficult to recall what they experienced in the period prior to their doctor’s appointment. A video diary may catch events and activities that may be missed otherwise (10,24,25).

Active Methods

For most children, active methods like playing with puppets, drama, or role play are enjoyable (16). It may be easier to communicate through such methods than to answer direct questions. It enables children to talk about sensitive issues, without personalizing it. A wide range of topics like children’s opinions on adults, forbidden behaviour, and activities can be discussed without fearing punishment Active methods can be used for the individual child or for groups (16,26). The use of puppets may be particularly helpful in exploring traumatic experiences in young children (15). Spending time and playing with children, especially when they are physically disabled, can be helpful to gain more insight in their needs (26).

Mosaic Approach

According to Malaguzzi (27), children and young people possess “the hundred languages of children” (8). Finding appropriate ways in their hundred languages to communicate with them is crucial (11). Lack of suitable methods can exclude children unable to use the available methods (12). This is the reason Clark and Moss developed the “mosaic” approach in participatory research (28). The aim of the mosaic approach is to give children a choice about how they would like to participate. They can choose among verbal, written, visual, and active methods, so they are able to select the one that suits them best (22). Each tool chosen by individual children forms one piece of the research method mosaic. This approach eases the participation of children by recognizing their wide range of competencies (3). The method can be used for a variety of purposes. Furthermore, as the diversity of methods is greater, the variety of answers to one question will be greater, which adds richness to the research. Still, the major disadvantage of the mosaic approach is the implication for processing obtained data, which gets more and more challenging when several participatory methods are being used to answer one research question (22).

General Considerations for Using Participatory Methods in Pediatric Medical Research

The use of pediatric participatory research methods is only acceptable when it adds something to the research and when it has no risk of being harmful to the child (3,8,9). When researchers choose to use participatory methods, they should be aware that it takes additional time, resources, and skills, to create successful participation (12). Therefore, proper preparation is essential. According to Smith et al. (9), four questions need to be answered prior to involve children in research: “can we make participatory research with children and young people work, will the results be accepted as legitimate findings, should we undertake this kind of research, and is it worth the additional demands on time, resources, and expertise? Then, after the decision is made to involve children, a suitable participatory method must be chosen.

Before choosing a participatory method, the objectives of the involvement must be clearly defined. The tools used must generate useful and relevant data, and therefore, they must be appropriate to the developmental stage and capacities of the children involved (2). Preschool children possess different skills than school-aged children, and they often lack writing and verbal skills (8,29). However, stages of development and levels of maturity differ not only in age but also in time and in place. Race, ethnicity, social class, and religion are part of who children are and might help to determine which method could be suitable for them (11).

Second, the choice for one of the available participatory methods not only depends on child characteristics but also on the data that should be obtained. Quantitative data can be gained by self-completion questionnaires, administration of standardized tests or measures, structured interviews, or observation (14). Qualitative data can be attained by all other methods. Before using a specific method, one must think through whether the data produced by children should be structured in any way, in order to be able to analyze it.

Third, the contact with children must be thought over. When children and young people are involved in participatory research and when they are asked to share parts of their lives with researchers, it is important for them to know with whom they are sharing their information. They need to get to know the researcher, in order to gain trust. When contact between children and researchers last a long period of time, ending the contact must also be carefully thought over (21). At last, children should also always be aware of the possibility to leave early when they change their minds, without having to give a reason (21).

There is a need for well-designed participatory methods to integrate the goals of research and of children’s involvement. A complete description of a participatory method should include both techniques for obtaining data, as well as for processing this data. In this review, we described the current knowledge on participatory pediatric research and gave an overview and assessment of participatory methods for children.

We defined participatory methods as any method that can be used to obtain children’s views, aiming to involve them in the design and conduct of research. We found that data about participatory methods is limited. Available knowledge is mainly based on expert’s opinion, either participating children or researchers themselves. Examples of involving children in pediatric research are scarce, there are no comparative studies and reviews are predominantly focusing on other issues than participatory methods. We found that most researchers using participatory methods are not aiming to involve children in the design and conduct of pediatric research. Instead, the participatory method is used only to obtain research data on children’s views. On the ladder of participation, pediatric medical research reflects more tokenism instead of evolving into partnership: participatory methods are not yet used in order to perform meaningful child participation. Despite the relative lack of high-quality evidence, we were able to list five groups of pediatric participatory methods, their aims, characteristics, and limitations ( Table 3 ). Since all the methods described are suitable for creating meaningful participation: a successful partnership between children and researchers in pediatric research, the evidence for the different participatory methods presented here is worth considering.

According to literature, the choice for using one or more participatory methods should be based on both age and other social and demographic characteristics and on the type of data the researcher would like to obtain. In general, observational methods are most suitable for preschool children. Verbal and written methods are suitable for school-aged children and young people, while visual and active methods are suitable for children who are less able to communicate verbally and for discussing more sensitive issues. However, for these children, it is still necessary to explain their visual creations or active performances, in order to gain useful data. If the researcher interprets this himself, without listening to the child’s explanation, it cannot be called a participatory method and it even may be unethical to do (15). Considering the “hundred languages of children” and all the different child characteristics that should be considered, in our opinion, a mosaic approach seems most suitable to use in pediatric medical research. Unfortunately, for data processing, it is also the most complicated method (22).

The main limitation of this systematic review is the relative lack of data, which immediately underscores the need for further research. As Bird et al.(6) already concluded, reporting of participatory research with children must improve, for example by using the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and Public (GRIPP) checklist (30), in order to be able to assess successful and unsuccessful methodologies (4). When this has been done a few times for each participatory method, comparative studies into the differences and similarities and pros and cons can be executed properly. For now, researchers conducting participatory research with children can use this systematic review in order to weigh the current knowledge about the participatory methods presented.

Statement of Financial Support

Since no financial assistance was received, none of the authors have any financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

United Nation Convention on the Rights of the Child, article 12, 20-11-1989. (http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx.)

Whiting L. Involving children in research. Paediatr Nurs 2009;21:32–6.

Dockett S, Einarsdottir J, Perry B. Research with children: ethical tensions. J Early Child Res 2009;7:283–98.

National Institute of Health Research. INVOLVE’s definitions. What is public involvement in research? 2015. (http://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/.)

Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect 2014;17:637–50.

Bird D, Culley L, Lakhanpaul M. Why collaborate with children in health research: an analysis of the risks and benefits of collaboration with children. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2013;98:42–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG ; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41.

Gallacher LA, Gallagher M. Methodological immaturity in childhood research?: thinking through “participatory methods”. Childhood 2008;15:499–516.

Smith R, Monaghan M, Broad B. Involving young people as co-researchers: facing up to the methodological issues. Qual Soc Work 2002;1:191–207.

Gilchrist F, Rodd HD, Deery C, Marshman Z. Involving children in research, audit and service evaluation. Br Dent J 2013;214:577–82.

Clavering EK, McLaughlin J. Children’s participation in health research: from objects to agents? Child Care Health Dev 2010;36:603–11.

Bailey S, Boddy K, Briscoe S, Morris C. Involving disabled children and young people as partners in research: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41:505–14.

Dockett S, Einarsdottir J, Perry B. Young children’s decisions about research participation: opting out. Int J Early Years Educ 2012;20:244–56.

Shaw C, Brady LM, Davey C. Guidelines for Research With Children and Young People. London: NCB Research Centre, National Children’s Bureau, 2011:1–63.

Boyden J, Ennew J. Children in Focus – A Manual for Participatory Research With Children. 1st edn. Stockholm, Sweden: Save the Children Sweden, 1997:1–191.

Gibson F, Aldiss S, Horstman M, Kumpunen S, Richardson A. Children and young people’s experiences of cancer care: a qualitative research study using participatory methods. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:1397–407.

Veinot TC, Flicker SE, Skinner HA, et al. “Supposed to make you better but it doesn’t really”: HIV-positive youths’ perceptions of HIV treatment. J Adolesc Health 2006;38:261–7.

Morris C, Liabo K, Wright P, Fitzpatrick R. Development of the Oxford ankle foot questionnaire: finding out how children are affected by foot and ankle problems. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:559–68.

Milnes LJ, McGowan L, Campbell M, Callery P. Developing an intervention to promote young people’s participation in asthma review consultations with practice nurses. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:91–101.

Stinson JN, Sung L, Gupta A, et al. Disease self-management needs of adolescents with cancer: perspectives of adolescents with cancer and their parents and healthcare providers. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6:278–86.

Clarke S. Informing pre-registration nurse education: a proposal outline on the value, methods and ethical considerations of involving children in doctoral research. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 2014;37:265–81.

Horstman M, Aldiss S, Richardson A, Gibson F. Methodological issues when using the draw and write technique with children aged 6 to 12 years. Qual Health Res 2008;18:1001–11.

Bradding A, Horstman M. Using the write and draw technique with children. Eur J Oncol Nurs 1999;3:170–75.

Rich M, Lamola S, Amory C, Schneider L. Asthma in life context: video intervention/prevention assessment (VIA). Pediatrics 2000;105:469–77.

Buchbinder MH, Detzer MJ, Welsch RL, Christiano AS, Patashnick JL, Rich M. Assessing adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a multiple perspective pilot study using visual illness narratives and interviews. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:71.e9–13.

Watson D, Abbott D, Townsley R. Listen to me, too! Lessons from involving children with complex healthcare needs in research about multi-agency services. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:90–5.

Malaguzzi, L. For an education based on relationships. Young Child 1993;11:9–13.

Clark A. Ways of seeing: using the Mosaic approach to listen to young children’s perspectives. In: Clark A, Kjorholt AT, Moss P, eds. Beyond Listening: Children’s Perspectives on Early Childhood Services. 1st edn. Bristol, England: Policy Press, 2005:29–49.

Gibson F. Conducting focus groups with children and young people: strategies for success. J Res Nurs 2007;12:473–83.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C, Barber R. The GRIPP checklist: strengthening the quality of patient and public involvement reporting in research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2011;27:391–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marijke Kars for her valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haijes, H., van Thiel, G. Participatory methods in pediatric participatory research: a systematic review. Pediatr Res 79, 676–683 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.279

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.279

This article is cited by

-

Key Insights into Developing Qualitative Concept Elicitation Work for Outcome Measures with Children and Young People

The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (2024)

-

Characterizing Canadian funded partnered health research projects between 2011 and 2019: a retrospective analysis

Health Research Policy and Systems (2023)

-

Embedding research codesign knowledge and practice: Learnings from researchers in a new research institute in Australia

Research Involvement and Engagement (2022)

-

Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews

Health Research Policy and Systems (2020)

-

A review of reviews on principles, strategies, outcomes and impacts of research partnerships approaches: a first step in synthesising the research partnership literature

Health Research Policy and Systems (2020)