Abstract

Background:

After 10 years of a decrease in smoking among young people in Sweden, we now have indications of increased smoking.

Aims:

To provide up-to-date information on the prevalence of smoking and smoke-associated respiratory symptoms in young adults in Sweden, with a special focus on possible gender differences.

Methods:

In the West Sweden Asthma Study, a detailed postal questionnaire focusing on asthma, respiratory symptoms, and possible risk factors was mailed to 30,000 randomly selected subjects aged 16–75 years. The analyses are based on responses from 2,702 subjects aged 16–25 years.

Results:

More young women than men were smokers (23.5% vs. 15.9%; p<0.001). Women started smoking earlier and smoked more. Symptoms such as longstanding cough, sputum production, and wheeze were significantly more common in smokers. In the multiple logistic regression analysis, smoking significantly increased the risk of recurrent wheeze (odds ratio (OR) 2.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 3.0)) and sputum production, (OR 2.4 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.1)).

Conclusions:

The alarmingly high prevalence of smoking among young women was parallel to a similarly high prevalence of bronchitis symptoms. This is worrisome, both in itself and because maternal smoking is a risk factor for illness in the child. Adverse respiratory effects of smoking occur within only a few years of smoking initiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of smoking has been decreasing among Swedish teenagers since the end of the 1990s.1 However, we can now see an increase in smoking prevalence among high school teenagers. A recent investigation by the Swedish National Institute of Public Health verified this increase, which is particularly obvious among girls.1 In 15-year-old girls, smoking at least once a week increased from 10% in 2005–2006 to 16% in 2009–2010.1 In 2012, even higher figures were reported from the Stockholm high schools where 37% of 17-year-old girls and 29% of boys smoked regularly.2 Similarly, recent national Swedish statistics show that the general trend of decreased smoking in the population is no longer present in young women aged 16–29 years, where daily smoking increased from 10% in 2009 to 13% in 2011.3

Smoking rates have traditionally been higher in men, but women are increasingly starting to smoke at an age equivalent to that of men.4 In the age group 15–24 years, the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) recently reported current smoking prevalence to be 29% in women and 24% in men in the UK.4 A common finding in many of the studies published in recent years is the increased smoking in young women. Smoking habits in young women thereby differ from a general trend of decreased smoking rates.1,3,4

The increased smoking prevalence is worrisome since smoking is related to several adverse effects on the smoker's health. In addition, the increased prevalence of smoking in teenage girls is alarming since maternal smoking during pregnancy negatively affects the offspring and increases the risk of low birth weight, sudden infant death syndrome, and wheezing illness.5–8 While many smoke-related diseases may take decades to develop, other adverse health effects such as wheeze and symptoms of bronchitis may be induced after only a few years of smoking.

The aim of this study was to provide up-to-date information on the prevalence of smoking and smoke-associated respiratory symptoms among teenagers and young adults in Sweden, with a special focus on gender differences.

Methods

Study area and population

The study area is the West Gothia Region in western Sweden including the city of Gothenburg, the second largest city in Sweden with about 800,000 inhabitants in the metropolitan area. The population of the entire region is more than 1.5 million, corresponding to one-sixth of the Swedish population.

Study population and questionnaire

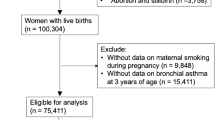

In 2008 a self-administered questionnaire was mailed to 30,000 inhabitants aged 16–75 years. A sample of 15,000 subjects was randomly selected from the metropolitan area of Gothenburg and 15,000 subjects were similarly selected from the rest of the region.9,10 The Swedish Population Register provided the names and addresses. A study of non-responders verified a good representativeness of the participants regarding respiratory symptoms and airway diseases.11 This paper is based on the 2,702 subjects aged 16–25 years who responded to the questionnaire.

The questions were based on the Swedish OLIN study questionnaire12–16 which contains items about obstructive respiratory symptoms and diseases, smoking, and other possible determinants of disease. The questionnaire was developed mainly from the British Medical Research Council questionnaire and has been used in several large-scale studies in the Nordic and Baltic countries.12–16 A comparison of the OLIN and Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) questionnaires concludes that questions about bronchitis are more detailed in the OLIN questionnaire.17 Questions on common asthma symptoms are similar or identical in the two questionnaires, and they yielded similar estimates of prevalence of respiratory symptoms and diseases in the same population.17 The definitions used are presented in Box 1.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Gothenburg.

Analyses

Ten per cent of the data were computerised twice to check the quality of the computerisation. Errors amounted to 0.1–0.2% of the computerised data, with only a few exceptions. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons of proportions were tested with Fisher's exact test. The Mantel-Haenszel test for trend was used where appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple logistic regression was used to calculate risk factors for symptoms and diseases, and risks were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Participation

Responses were obtained from 2,702 subjects (1,548 women and 1,154 men), comprising 58.0% of the eligible women and 42.4% of the eligible men (p<0.001). Of these, 1,444 lived in the metropolitan area of Gothenburg and 1,258 in the rest of the region.

The previous study of non-responders showed that male gender, young age, and smokers were over-represented among the non-responders.11 A similar pattern was seen in the age group 16–25 years, where 55.6% of the non-responders were men while 42.7% of the responders were men. The prevalence of smokers was 26.6% among the non-responders aged 16–25 years compared with 20.4% in responders, with a female predominance of smokers among the non-responders as well.

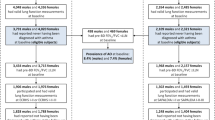

Prevalence and gender differences in smoking habits

Significantly more young women than men were active smokers (23.5% vs. 15.9%; p<0.001) and ex-smokers (7.2% vs. 4.1%; p=0.001) (Figure 1). Furthermore, the smoking women smoked significantly more than the men (p value for test for trend <0.001). Of the smoking women 42.0% smoked 5–14 cigarettes per day vs. 27.1% among the smoking men, while 10.4% vs. 6.5% smoked 15–24 cigarettes (Figure 2).

The women had also started to smoke earlier (p value for test for trend <0.001). Of the smoking women, 58.0% had started smoking between 11 and 15 years of age compared with 44.4% of the men, while 38.7% of the women reported started smoking between 16 and 20 years vs. 47.8% of men (Figure 3). The mean age at smoking initiation was 14.9 years for women and 15.8 years for men.

Differences between the metropolitan area of Gothenburg and the rest of the West Gothia region were small, although there was a slightly higher prevalence of non-smokers in the rest of the region (75.4% vs. 71.5%; p=0.025).

Smoking status by parental smoking

Of the subjects with smoking parents, 36.9% were smokers compared with 18.0% in subjects whose parents did not smoke (p<0.001). Of all young smokers, 52.2% had smoking parents while 75.4% were never-smokers among the subjects with non-smoking parents.

Prevalence of airway symptoms by smoking status

Most airway symptoms such as longstanding cough, sputum production, wheeze, waking with chest tightness, and nasal obstruction were significantly more common in smokers than in never-smokers (Table 1). This was particularly true for sputum production and longstanding cough. The overall prevalence of longstanding cough was 13.1% (15.0% in women and 10.7% in men, p=0.001) and of sputum production was 15.4% (16.9% in women and 13.4% in men, p=0.015). The prevalence of most airway symptoms also tended to be higher among ex-smokers than among never-smokers.

Risk factors

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, smoking significantly increased the risk of recurrent wheeze (OR 2.0 (95% CI 1.4 to 3.0)) and sputum production (OR 2.4 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.1)) (Table 2). Similarly, occupational exposures to dust, gases, or fumes increased the risk of using asthma medication and having attacks of shortness of breath, recurrent wheeze, sputum production, and allergic rhinitis. As expected, a family history of asthma and allergy as well as female gender was associated with an increased risk of asthma medication, attacks of shortness of breath, and recurrent wheeze. When a family history of both asthma and allergy was present, the risk of using asthma medication increased six-fold (OR 6.2 (95% CI 4.4 to 8.9)) (Table 2).

Effect modification by gender

When we tested the interaction between gender and smoking in the same adjusted model we found statistically significant interactions (with odds ratios of about 3) between female sex and current smoking for all respiratory symptoms investigated (attacks of shortness of breath during the last 12 months OR 3.3 (95% CI 1.3 to 8.4), recurrent wheeze OR 2.8 (95% CI 1.1 to 7.4), and sputum production OR 3.0 (95% CI 1.7 to 5.2)) and for asthma medication OR 3.1 (95% CI 1.1 to 8.5). However, when years of smoking or current number of cigarettes smoked daily were also included in the multiple logistic regression models, the observed interactions were no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

Main findings

The main findings of this study are that smoking is more common among young Swedish people than expected, especially among young women, and that adverse respiratory effects are seen after only a few years of smoking. Women start smoking earlier and smoke more. The prevalence of bronchitis symptoms is alarmingly high, with one out of four reporting longstanding cough and sputum production. In the multiple logistic regression analysis, smoking significantly increased the risk of recurrent wheeze and sputum production.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Our findings are in line with recent statistics from the Swedish National Institute of Public Health.1 In that survey, the prevalence of smoking in 15-year-old girls was 16% in 2009–2010 compared with 10% in 2005–2006, while the corresponding prevalence in boys was 13% and 8%. In Northern Sweden, in 2003, the prevalence of smokers among 15-year-old teenagers was even lower (9% of girls and only 3% of boys).18 The prevalence of active smoking in our study was even higher in the age group 16–25 years (23.5% in women and 15.9% in men).

The study in Northern Sweden also showed that significantly more young women than young men smoke.18 A similar pattern is seen in Norway.19 Furthermore, in our study, the women also started smoking earlier than the men. On the other hand, the use of snuff is more common among young men.18

Although smoking has decreased since 1990 when the overall smoking prevalence among adults aged 20–44 years in Sweden was 30–40%,20 we were surprised by the high smoking prevalence we found among young women. The present smoking prevalence is, in fact, comparable to that found in a study in Northern Sweden in 1996.21 In that study, smoking in the age group 20–29 years was 26% among women and 16% among men. This contradicts a general conception of a clear-cut decrease in smoking prevalence during the last 10–15 years among young adults. Recent longitudinal Swedish surveys report an increased smoking prevalence in young women in the last years.1,3 The present results are in line with those reports. However, since the present study reports data from a single survey and compares the findings with other studies, we cannot conclude that the study itself shows an increased prevalence of smoking.

Female smoking dominance is not seen in all countries — for example, in Finland and Estonia smoking is more common among young men.15,22 In middle-income and low-income countries, smoking rates are higher in men.4 However, as pointed out in the GATS survey, women in those countries also start to smoke at an early age.4 With increasing economic growth, a development similar to that in high-income countries could be expected, with the smoking prevalence becoming higher in women.

Smoking parents is a strong risk factor for the child to become a smoker. Smoking among teenagers is twice as common among those with at least one smoking parent compared with those with no parent who smokes.23

The overall prevalence of respiratory symptoms (13–15%) with a significant female dominance was higher than that reported in subjects of similar age in a large-scale Swedish study performed 19 years before our study.24 That study used identical questions about symptoms and yielded an overall prevalence, including smokers, of 10–12%. A Swedish study among teenagers performed in 1987 found the prevalence of longstanding cough to be 3–5%.25 The Swedish part of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) with an age distribution from 20 up to 44 years did not report prevalence by age group, but the overall prevalence of bronchitis symptoms was similar to ours, although our study sample was considerably younger.20 As symptoms of bronchitis tend to increase with age,12,24 a comparison with the ECRHS results also suggests an increase in young subjects.

Smoking was associated with most respiratory symptoms. Indices of the adverse effects of smoking, such as a longstanding cough and sputum production, are already seen at this young age. The results show that adverse effects of smoking appear in a surprisingly short time and call attention to the short-term consequences for young people. The association with recurrent wheeze and sputum production remained after adjustment for other risk factors for respiratory symptoms.

In the same adjusted model there were clear interactions between female sex and current smoking for all asthma symptoms investigated. These findings are in line with several studies indicating an increased susceptibility to tobacco smoke among women.26,27 However, in our study, the stronger effect of smoking in women on sputum production and recurrent wheeze seemed to be explained by women starting earlier and smoking more.

The fact that smoking is common today in young women and that there are indications of increased smoking in young women is particularly worrying.1,3 Maternal smoking during pregnancy is a well-known risk factor for wheezing illness and bronchial hyper-responsiveness in the child.7,8 The effects in terms of increased risk of asthma and impaired lung function are longstanding and may be seen even up to adulthood.28–31 Furthermore, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke during childhood is associated with an increased prevalence of asthma in adults.32 Growing up with smoking parents increases the risk of the child becoming an active smoker, which in turn is a risk factor for respiratory symptoms and asthma.28,33 Hence, a vicious circle is established.

An explanation for the high smoking prevalence among young women could be that, today, girls and young women tend to adopt the cigarette and alcohol habits previously seen among boys and young men. In addition, some girls are attracted by the side-effect that smoking makes it easier for them to stay slim. Smoking in Sweden is closely linked to a low level of education and lower socioeconomic status.3 As in several other European countries, Sweden has in recent years faced problems with youth unemployment which could contribute to the high smoking prevalence seen. Another factor could be an influence by second-generation immigrants who come from cultures with a high prevalence of smokers. Just as smoking parents is a strong risk factor for the child to start smoking, we know that teenagers are influenced by the smoking habits of their friends.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

The findings highlight the importance of long-term efforts and openness to the continuously changing forces that drive smoking initiation in the young. Maternity care in Sweden has nearly full coverage and represents an important opportunity to convince parents-to-be to quit smoking in light of the health risks in the unborn child. Moreover, smoking parents also have the possibility to influence their children not to smoke. However, it requires an active effort by the parents and a discussion of the adverse effects of tobacco, and smoking parents could thus be a key group on which to focus future anti-smoking efforts.

One practical measure that could be taken to counteract the worrying trend is a rise in the price of tobacco. The WHO convention on tobacco control points out that price and tax measures are effective and important means of reducing tobacco consumption among young persons in particular.34 In the 1990s the health risk of smoking was regularly discussed in Swedish schools. During the last decade, however, this practice has subsided. Our study highlights the importance of schools as a primary vehicle for tobacco awareness among children.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of the study include the population-based design and the large study sample. Another strength is the well-established questionnaire used, with questions that thoroughly cover smoking and symptoms of bronchitis and obstructive airway disease.

Weaknesses of the study are those inherent in questionnaire-based studies — namely, some uncertainty regarding the validity of answers. However, it is unlikely that the study participants exaggerated their smoking. Instead, it is more likely that smoking is underestimated in the answers. Furthermore, this part of the West Sweden Asthma Study did not include lung function testing. Another limitation of the study is the non-response rate. The previous study of non-responders11 was therefore supplemented with an analysis that verified that smoking was also somewhat more common among non-responders in the age group 16–25 years, especially among the women. Thus, our results, if anything, underestimate the prevalence of smokers. Furthermore, since smoking was also more common in women among the non-responders, the lower response rate in men probably does not pose an issue in interpreting the findings.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of smoking among young women found in this study is worrying, both in itself and since smoking is a risk factor for illness in the children of smoking women. In addition to a higher smoking prevalence, the women started smoking earlier and smoked more than the men. Adverse respiratory effects were seen after only a few years of smoking. The association between smoking and recurrent wheeze and sputum production remained after adjustment for other risk factors for respiratory symptoms. Compared with the results of previous studies in people of similar ages, a higher prevalence of bronchitis symptoms was found. The results call for continuous anti-smoking efforts. Effective smoking prevention programmes, particularly among young women, are needed.

References

Swedish National Institute of Public Health [Statens folkhälsoinstitut]. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), results from Sweden of the 2009/10 WHO study [Svenska skolbarns hälsovanor 2009/10. Grundrapport]. R 2011:27, Östersund, Sweden, 2011. http://www.fhi.se/PageFiles/12995/R2011-27-Svenska-skolbarns-halsovanor-2009-2010-grundrapport.pdf (accessed 5 Nov 2012).

City of Stockholm. The Stockholm questionnaire 2012 [Stockholmsenkäten 2012]. Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. http://www.stockholm.se/Fristaende-webbplatser/Fackforvaltningssajter/Socialtjanstforvaltningen/Utvecklingsenheten/Prevention/Stockholmsenkaten1/ (accessed 5 Nov 2012).

Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen], Swedish National Institute of Public Health [Statens folkhälsoinstitut]. Public health in Sweden: Annual report 2012 [Folkhälsan i Sverige: Årsrapport 2012]. Stockholm and östersund, Sweden, 2012. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/18623/2012-3-6.pdf (accessed 5 Nov 2012).

Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet 2012;380(9842):668–79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X

Brooke OG, Anderson HR, Bland JM, Peacock JL, Stewart CM . Effects on birthweight of smoking, alcohol, caffeine, socioeconomic factors, and psychosocial stress. BMJ 1989;298(6676):795–801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.298.6676.795

Alm B, Milerad J, Wennergren G, et al. A case-control study of smoking and sudden infant death syndrome in the Scandinavian countries, 1992 to 1995. Arch Dis Child 1998;78(4):329–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.78.4.329

Stein RT, Holberg CJ, Sherrill D, et al. Influence of parental smoking on respiratory symptoms during the first decade of life: the Tucson Children's Respiratory Study. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149(11):1030–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009748

Gilliland FD, Li YF, Peters JM . Effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy and environmental tobacco smoke on asthma and wheezing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163(2):429–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2006009

Lötvall J, Ekerljung L, Rönmark EP et al. West Sweden Asthma Study: prevalence trends over the last 18 years argue no recent increase in asthma. Respir Res 2009;10:94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-10-94

Ekerljung L, Bossios A, Lötvall J, et al. Multi-symptom asthma as an indication of disease severity in epidemiology. Eur Respir J 2011;38(4):825–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00143710

Rönmark EP, Ekerljung L, Lötvall J, Torén K, Rönmark E, Lundbäck B . Large scale questionnaire survey on respiratory health in Sweden: effects of late- and non-response. Respir Med 2009;103(12):1807–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2009.07.014

Lundbäck B, Nyström L, Rosenhall L, Stjernberg N . Obstructive lung disease in northern Sweden: respiratory symptoms assessed in a postal survey. Eur Respir J 1991;4(3):257–66.

Kotaniemi J, Lundbäck B, Nieminen M, Sovijärvi A, Laitinen L . Increase of asthma in adults in Northern Finland — a report from the FinEsS study. Allergy 2001;56(2):169–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.056002169.x

Meren M, Jannus-Pruljan L, Loit HM, et al. Asthma, chronic bronchitis and respiratory symptoms among adults in Estonia. Respir Med 2001;95(12):954–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/rmed.2001.1188

Pallasaho P, Lundbäck B, Meren M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for asthma and chronic bronchitis in the capitals Helsinki, Stockholm, and Tallinn. Respir Med 2002;96(10):759–69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/rmed.2002.1308

Ekerljung L, Rönmark E, Larsson K, et al. No further increase of incidence of asthma: incidence, remission and relapse of adult asthma in Sweden. Respir Med 2008;102(12):1730–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.07.011

Ekerljung L, Rönmark E, Lötvall J, Wennergren G, Torén K, Lundbäck B . Questionnaire layout and wording influence prevalence and risk estimates of respiratory symptoms in a population cohort. Clin Respir J 2013;7(1):53–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-699X.2012.00281.x

Hedman L, Bjerg A, Perzanowski M, Sundberg S, Ronmark E . Factors related to tobacco use among teenagers. Respir Med 2007;101(3):496–502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.001

Tollefsen E, Bjermer L, Langhammer A, Johnsen R, Holmen TL . Adolescent respiratory symptoms — girls are at risk: the Young-HUNT study, Norway. Respir Med 2006;100(3):471–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.06.007

Björnsson E, Plaschke P, Norrman E, et al. Symptoms related to asthma and chronic bronchitis in three areas of Sweden. Eur Respir J 1994;7(12):2146–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.94.07122146

Lindström M, Kotaniemi J, Jönsson E, Lundbäck B . Smoking, respiratory symptoms, and diseases: a comparative study between northern Sweden and northern Finland: report from the FinEsS study. Chest 2001;119(3):852–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.119.3.852

Pallasaho P, Juusela M, Lindqvist A, Sovijärvi A, Lundbäck B, Rönmark E . Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis doubles the risk for incident asthma — results from a population study in Helsinki, Finland. Respir Med 2011;105(10):1449–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.04.013

Swedish National Institute of Public Health [Statens folkhälsoinstitut]. Teenagers on tobacco 2009 — habits, knowledge and attitudes [Tonåringar om tobak — vanor, kunskaper och attityder]. R 2010:20, Östersund, Sweden, 2010. http://www.fhi.se/PageFiles/10883/R-2010-20-Tonaringar-om-tobak.pdf (accessed 5 Nov 2012).

Larsson L, Boëthius G, Uddenfeldt M . Differences in utilization of asthma drugs between two neighbouring Swedish provinces: relation to symptom reporting. Eur Respir J 1993;6(2):198–203.

Norrman E, Rosenhall L, Nyström L, Bergström E, Stjernberg N . High prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in teenagers in Northern Sweden. Eur Respir J 1993;6(6):834–9.

Xu X, Li B, Wang L . Gender difference in smoking effects on adult pulmonary function. Eur Respir J 1994;7(3):477–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.94.07030477

Langhammer A, Johnsen R, Holmen J, Gulsvik A, Bjermer L . Cigarette smoking gives more respiratory symptoms among women than among men. The Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT). J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54(12):917–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.54.12.917

Goksör E, Åmark M, Alm B, Gustafsson PM, Wennergren G . The impact of pre- and post-natal smoke exposure on future asthma and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Acta Paediatr 2007;96(7):1030–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00296.x

Goksör E, Gustafsson PM, Alm B, Åmark M, Wennergren G . Reduced airway function in early adulthood among subjects with wheezing disorder before two years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008;43(4):396–403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ppul.20798

Piippo-Savolainen E, Korppi M . Wheezy babies — wheezy adults? Review of long-term outcome until adulthood after early childhood wheezing. Acta Paediatr 2008;97(1):5–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00558.x

Bjerg A, Hedman L, Perzanowski M, Lundbäck B, Ronmark E . A strong synergism of low birth weight and prenatal smoking on asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatrics 2011;127(4):e905–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2850

Larsson ML, Frisk M, Hallström J, Kiviloog J, Lundbäck B . Environmental tobacco smoke exposure during childhood is associated with increased prevalence of asthma in adults. Chest 2001;120(3):711–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.120.3.711

Hedman L, Bjerg A, Sundberg S, Forsberg B, Ronmark E . Both environmental tobacco smoke and personal smoking is related to asthma and wheeze in teenagers. Thorax 2011;66(1):20–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.143800

World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. Updated 2004, 2005. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf (accessed 22 Jan 2013).

Acknowledgements

Handling editor David Bellamy

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Funding The study was supported by the VBG Group Herman Krefting Foundation for Asthma and Allergy Research, the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, the Research Foundation of the Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association, and the Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, Västra Götaland Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All co-authors made substantial contributions to the study. BL and JL designed the West Sweden Asthma Study. LE had the main responsibility for the statistical calculations. GW and BL had the main responsibility for writing the manuscript. All co-authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript and approved the submitted version of the paper. GW and BL are guarantors of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wennergren, G., Ekerljung, L., Alm, B. et al. Alarmingly high prevalence of smoking and symptoms of bronchitis in young women in Sweden: a population-based questionnaire study. Prim Care Respir J 22, 214–220 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00043

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00043

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence trends in respiratory symptoms and asthma in relation to smoking - two cross-sectional studies ten years apart among adults in northern Sweden

World Allergy Organization Journal (2014)