Abstract

Background:

Polysensitisation is a frequent phenomenon in patients with allergic rhinitis. However, few studies have investigated the characteristics of polysensitised children, especially in primary care.

Objectives:

This analysis describes the patterns of sensitisation to common allergens and the association with age, gender, and clinical symptoms in children in primary care diagnosed with allergic rhinitis.

Methods:

Cross-sectional data from two randomised double-blind placebo-controlled studies were used to select children aged 6–18 years (n=784) with a doctor's diagnosis of allergic rhinitis or use of relevant medication for allergic rhinitis in primary care. They were assessed for age, gender, specific IgE (type and number of sensitisations), nasal and eye symptom scores.

Results:

In 699 of the 784 children (89%) with a doctor's diagnosis or relevant medication use, a positive IgE test for one or more allergens was found. Polysensitisation (≥2 sensitisations) was found in 69% of all children. Sensitisation was more common in children aged 9–13 than in younger children aged 5–8 years (p=0.03). Monosensitisation and polysensitisation were not significantly different in girls and boys. The severity of clinical symptoms did not differ between polysensitised and monosensitised children, but symptoms were significantly lower in non-sensitised children.

Conclusions:

Polysensitisation to multiple allergens occurs frequently in children with allergic rhinitis in general practice. Overall, clinical symptoms are equally severe in polysensitised and monosensitised children. Treatment decisions for allergic rhinitis should be made on the basis of a clinical history and allergy testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is an inflammatory disease of the nasal membrane which is characterised by symptoms such as sneezing, rhinorrhoea, nasal congestion, and nasal itching. It is often associated with eye symptoms such as tearing, redness, and itching. Allergic rhinitis is caused by sensitisation to one or more aeroallergens. It is a common chronic disorder among children,1,2 and can significantly impair quality of life. It is associated with a number of common comorbidities including asthma, sinusitis, and otitis media.1,2 Early intervention might minimise the likelihood of progression to more severe allergic diseases in children, including asthma.3

Polysensitisation might be a phenomenon that is clinically relevant. Several studies have pointed out that up to 90% of patients are polysensitised.4,5 Only a few studies have addressed and discussed polysensitisation in children and have been performed in referral centres. Kim et al. concluded that the symptom scores and levels of total IgE were higher in polysensitised children than in monosensitised children.6

A study of both adults and children indicated that polysensitised individuals have atopic disease with a more severe course.5 Another study showed that polysensitisation was associated with a significantly poorer quality of life.7 More recently, Baatenburg de Jong and colleagues concluded that polysensitisation is common in children of school age, particularly boys.8

Persisting or recurrent symptoms of rhinitis can occur in both allergic and non-allergic disorders, and this overlap can confound the diagnosis and therapy.9–11 Assessment of allergic sensitisation is important in the diagnosis and management of allergic disease throughout childhood because it enables tailored allergen-specific avoidance measures, allergen-specific treatment, relevant pharmacotherapy and can identify infants at increased risk of developing allergic diseases later in life.10,11 In many European countries such as the UK and the Netherlands, the majority of patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma are diagnosed and treated by primary care physicians.12,13

The aim of the current study is to describe the patterns of sensitisation to common allergens and the association with age, gender, and clinical symptoms in children with allergic rhinitis in primary care who were eligible for a study investigating the efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with either grass pollen allergen or house dust mite (HDM) allergen.

Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional data from two randomised double-blind placebo-controlled studies investigating the efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with either grass pollen allergen or HDM allergen in 6–18-year-old children with allergic rhinitis and a proven grass pollen or HDM allergy in primary care were used. The present study used data from the recruitment phase. Written informed consent was obtained from parents of all children and from children aged 12–18 years. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam. Detailed descriptions of the design and results of both studies have been published elsewhere and are summarised below.14–16

Recruitment

General practitioners in the south-western part of the Netherlands selected children aged 6–18 years from their computerised patient records with either a clinical diagnosis of hay fever/allergic rhinitis (ICPC code R97) or with relevant medication use (i.e. antihistamines for systemic use, nasal corticosteroids, topical decongestants, topical antihistamines). After telephone screening, a house visit took place for those who agreed (children/parents) to further participation. During the telephone screening, children who had no (or only a short) history of allergy or who had a low symptom score were excluded.14,15

During the house visit, which in both studies took place in September-October, symptom scores were recorded and a blood sample was collected by a research assistant.

Symptom scores

Rhinitis symptom scores: the intensity of the symptoms ‘rhinorrhoea’, ‘blocked nose’, ‘sneezing’, ‘itching’ was subjectively assessed according to a grading scale from 0 to 3 (0 = no complaints, 1 = minor complaints, 2 = moderate complaints and 3 = serious complaints). The maximum score was 12.

Conjunctivitis symptom score: the intensity of the symptom ‘itching eyes’ was subjectively assessed according to a grading scale from 0 to 3 as described above, with a maximum score of 3.

In the grass pollen study, the participants rated their nose and eye symptoms during the previous grass pollen season (i.e. retrospectively in the period May-August) and during the past week. In the HDM study the children rated their symptoms of the last three months (i.e. retrospectively in the period July-September or August-October) and during the past week.

Allergen-specific IgE

A blood sample was collected for the assessment of allergen-specific IgE to grass pollen, birch pollen, HDM, cat dander, and pets if present at home (RAST CAP-Phadiatop®, Pharmacia Diagnostics AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Sensitisation to an allergen was defined as positive when allergen-specific IgE levels were 0.35kU/L or higher (≥ class 1).1,2

Monosensitisation and polysensitisation

Subjects sensitised to only one tested allergen were defined as monosensitised and those sensitised to two or more tested allergens were defined as polysensitised. For polysensitised children, we distinguished sensitisation patterns of two, three, and four or more (maximum seven) sensitisations.

We analysed the different perceptions of nasal and eyes symptoms in: (1) non-sensitised children; (2) children with a grass pollen sensitisation but not a HDM sensitisation; (3) children with a HDM sensitisation but not a grass pollen sensitisation; and (4) children with both a grass pollen and HDM sensitisation.

In the grass pollen study, 307 children were visited and in the HDM study 500 children (total of 807 children). For the present analysis we only included children who fulfilled the criteria of completely recorded symptom scores (nasal and eye) and an analysed blood sample for allergen-specific IgE test (irrespective of the result).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The differences between means were analysed by the independent- samples t test and differences between proportions were analysed by the χ2 test.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The study population consisted of 784 children with a doctor's diagnosis of allergic rhinitis or prescription of relevant allergy medication. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the groups are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 12.2 years; 57% were boys. The mean nasal symptom score was 6 and the mean eye symptom score over the last three months was 1.4.

Sensitisation patterns, age groups and gender

Sensitisation to an allergen was found in 89% of the patients (n=699). Table 1 shows that polysensitisation was found in 69% of all children (538/784). The mean number of positive tested sensitisation was 2. Sensitisation to two tested allergens was found in 298 of the 784 children (38%), three positive IgE tests for specific allergens were found in 166 children (21%), and sensitisation to four or more allergens in 174 children (22%). The mean levels of specific grass pollen IgE and HDM IgE in children who were sensitised were 41.8kU/L and 26.9kU/L, respectively (Table 1).

The co-sensitisation patterns to grass pollen, HDM, birch pollen, and cat dander are presented in Table 2. In children sensitised to HDM, 79% also had co-sensitisation to grass pollen. In children sensitised to birch pollen, 97% had co-sensitisation to grass pollen. In children sensitised to cat dander, 88% had co-sensitisation to HDM and 93% had co-sensitisation to grass pollen.

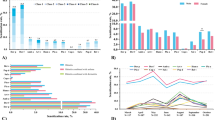

The percentage of children in each sensitisation group for the different age groups is presented in Figure 1A. Sensitisation was more common in children aged 9–13 years than in younger children aged 5–8 years (p=0.03). The difference between the oldest age group (14–17 years) and the youngest age group did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08). This was also seen between children aged 9–13 years and children aged 14–17 years (p=0.88).

The gender distribution in the sensitisation groups is shown in Figure 1B. The sensitisation pattern was not significantly different between girls and boys (p=0.11).

Self-reported nasal and eye symptom scores

The mean nasal symptoms during the last three months was significantly lower in non-sensitised children than in monosensitised and polysensitised children (Figure 2A; p=0.001). This was also seen for the mean eye symptom score during the last three months in non-sensitised children compared with monosensitised and polysensitised children (Figure 2B; p<0.0001). There was no significant difference between monosensitised and polysensitised children in nasal and eye symptoms.

Perception of nasal and eye symptom scores in children with different sensitisation patterns during last 3 months. Perceived severity of (A) nasal symptoms and (B) eye symptoms during last 3 months (mean±SE) in non-sensitised, monosensitised, and polysensitised children. Perceived severity of (C) nasal symptoms and (D) eye symptoms during last 3 months (mean±SE) in non-sensitised children, children with both house dust mite (HDM) sensitisation and grass pollen sensitisation, children with HDM sensitisation (without grass pollen sensitisation), and children with grass pollen sensitisation (without HDM sensitisation)

As shown in Figure 2C, the perceived severity of nasal symptoms during the last three months was significantly higher in children with HDM or grass pollen sensitisation or a combination of both allergens than in children without a sensitisation (p<0.001 and p=0.001). There was no significant difference between children sensitised to HDM or grass pollen only and children with a sensitisation to both allergens.

The perceived severity of itching eye symptoms during the last three months was significantly higher in children with grass pollen sensitisation (without HDM sensitisation) than in children with only HDM sensitisation (without grass pollen sensitisation) or children with sensitisation to both grass pollen and HDM (p<0.001 and p=0.008). Children with sensitisation to both grass pollen and HDM reported higher eye symptoms than those with HDM sensitisation only (p=0.009; Figure 2D). Compared with non-sensitised children, the perceived severity of itching eye symptoms during the last three months in children with HDM sensitisation (without grass pollen sensitisation) or grass pollen sensitisation (without HDM sensitisation) or both was significantly higher (p=0.02 and p<0.0001).

Discussion

Main findings

This study shows that polysensitisation is frequent in children with allergic rhinitis in primary care. Clinical symptoms are equally severe in polysensitised children and in monosensitised children and are less severe in non-sensitised children. Children with grass pollen sensitisation (without HDM sensitisation) experienced significantly greater eye symptoms during the last three months than children with HDM sensitisation (without grass pollen sensitisation), or both.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study, conducted in a large group of children with allergic rhinitis in primary care, gives an insight into the different patterns of sensitisation and confirms that polysensitisation is common in primary care. In the Netherlands the majority of patients with allergic rhinitis are treated by primary care physicians. Recent articles address the importance of primary care in the treatment and management of allergic rhinitis.9,17 For these reasons, we considered it important to perform this analysis in a population that was seen in primary care. Future studies designed exclusively to explore the clinical relevance of different (co)sensitisation patterns in children should be encouraged.

Both selection bias and reporting bias may have affected our results. The studied population was screened for two randomised double-blind placebo-controlled studies, comparing the efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with either grass pollen allergen or HDM allergen with placebo. This could potentially introduce a bias with regard to the differences between clinical trial participants (i.e. willing to participate in a trial, more severe complaints) and the general population. Also, before inclusion a selection bias could have been introduced. Patients with symptoms due to allergens other than HDM or grass pollen probably did not apply for both studies. These patients could have a monosensitisation. However, it is also possible that these patients are sensitised to multiple allergens but are mainly affected by an allergen that was not relevant for both studies.

We recognise that selection bias could have affected the results regarding the standard set of allergens that were tested (i.e. grass pollen, HDM, birch pollen, and cat dander). Allergen-specific IgE to other pet(s) were only determined if the pet was present at home. Children could thus be sensitised to, for example, dog dander but not tested if no dog was present at home. These patients are then incorrectly labelled as monosensitised, indicating that the true number of monosensitised children is even lower than was found.

Because the nasal and eye symptoms were assessed through interviews, misclassification bias is a concern. Both nasal and eye self-reported symptoms could be underestimated because of the different seasons when asking the symptoms.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Polysensitisation is a frequent phenomenon in subjects with allergic rhinitis. This finding is not new, as it has been reported in previous studies.5,8,18 However, these studies were performed in patients in a secondary care setting. In the present primary care study, we found similar results in children diagnosed with allergic rhinitis. About 75% of patients were sensitised to two or more allergens. Hence, primary care physicians should also be aware of the fact that patients can have multiple allergies.

The basis of diagnosing allergy consists of a good history and physical examination. However, the diagnosis cannot be confirmed on the basis of symptoms alone because both allergic and non-allergic conditions can present with similar symptoms.11 Knowledge of the type of sensitisation may affect general practitioners or other physicians in the way they advise children with allergic rhinitis or in the selection of aeroallergens for allergen immunotherapy.11,19 Also, confirmation that an allergen trigger is not the cause may prevent unnecessary lifestyle changes and discourage further allergy investigations.10,11,19

In our study, 11% of the children were not sensitised. These children visited their general practitioner for complaints of allergic rhinitis or they received relevant medication for allergic rhinitis. An explanation for the fact that these patients had a negative blood test could be that rhinitis symptoms might have been caused by non-immunological aspecific triggers (hyperreactivity) or by an allergen not tested. We tested the most common allergens in the Netherlands, but other allergens such as plants (mugwort) or moulds (Alternaria) could be responsible for these complaints.

A study in a paediatric population showed that children with polysensitisation had higher symptom scores and a poorer response to immunotherapy than monosensitised children. Polysensitisation seems to be characterised by more severe clinical outcomes compared with monosensitisation.6,18 However, in our study we found no difference in mean nasal and eye symptom scores in children with different sensitisation patterns. Similar results in adults were observed in a study by Malling and colleagues20 although, if we compared HDM monosensitisation and grass pollen monosensitisation, significant differences in eye symptoms were found. A grass pollen-induced allergic rhinitis is characterised by more eye symptoms than HDM-induced allergic rhinitis.1,2

In previous studies the risk of polysensitisation was shown to increase with age.8,21,22 For example, Fasce et al. concluded that the number of sensitisations increased with age and monosensitised children are likely to become polysensitised.21 In our study we found that increasing age was responsible for an increased expression of polysensitisation only in early adolescence. The causes of these age differences may be related to changes in the hormonal environment, environmental factors, and behavioural factors (e.g. less frequent outdoor exposure during childhood).23,24 We can assume there is a link between these factors, but the underlying pathophysiology is unclear.

It is known that, in childhood, allergic rhinitis is more common in boys than in girls.25,26 In our study we saw no difference in monosensitisation and polysensitisation between boys and girls. This is in contradiction to other studies where boys were more likely to be polysensitised than girls.6,8

Conclusion and implications for clinical practice

Sensitisation to multiple allergens occurs frequently in children with allergic rhinitis in general practice. Overall, clinical symptoms are equally severe in polysensitised and monosensitised children. Treatment decisions including allergen avoidance measures for allergic rhinitis and prescription of immunotherapy should be made on the basis of a clinical history and allergy testing.

References

Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108(5 Suppl):S147–334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.118891

Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA): 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy 2008;63:8–160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x

Liu AH . The allergic march of childhood. Med Sci Update 2006;23:1–7.

Migueres M, Fontaine JF, Haddad T, et al. Characteristics of patients with respiratory allergy in France and factors influencing immunotherapy prescription: a prospective observational study (REALIS). Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2011;24:387–400.

Ciprandi G, Alesina R, Ariano R, et al. Characteristics of patients with allergic polysensitization: the Polismail Study. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;40:77–83.

Kim KW, Kim EA, Kwon BC, et al. Comparison of allergic indices in monosensitized and polysensitized patients with childhood asthma. J Korean Med Sci 2006;21:1012–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2006.21.6.1012

Cirillo I, Vizzaccaro A, Klersy C, et al. Quality of life and polysensitization in young men with intermittent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005;94:640–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61321-X

Baatenburg de Jong A, Dikkeschei LD, Brand PLP . Sensitization patterns to food and inhalant allergens in childhood: a comparison of non-sensitized, monosensitized, and polysensitized children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2011;22:166–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.00993.x

Sachs A, Berger MY, Lucassen PLBJ, et al. Allergische en niet-allergische rhinitis M48 Eerste herziening. Huisarts en Wetenschap 2006;49:254–65.

Host A, Andrae S, Charkin S, et al. Allergy testing in children: why, who, when and how? Allergy 2003;58:559–69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00238.x

Ahlstedt S, Murray CS . In vitro diagnosis of allergy: how to interpret IgE antibody results in clinical practice. Prim Care Respir J 2006;15:228–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2006.05.004

Ryan D, van Weel C, Bousquet J, et al. Primary care: the cornerstone of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Allergy 2008;63:981–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01653.x

de Bot CMA, Moed H, Schellevis FG, et al. Allergic rhinitis in children: incidence and treatment in Dutch general practice in 1987 and 2001. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;20:571–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00829.x

de Bot CMA, Moed H, Berger MY, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of sublingual immunotherapy in children with house dust mite allergy in primary care: study design and recruitment. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-9-59

Roder E, Berger MY, Hop WC, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen is not effective in symptomatic youngsters in primary care. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:892–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.651

de Bot CMA, Moed H, Berger MY, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy not effective in house dust mite-allergic children in primary care. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;23:150–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01219.x

Costa DJ, Bousquet PJ, Ryan D, et al. Guidelines for allergic rhinitis need to be used in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:250–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00028

Ciprandi G, Contini P, Fenoglio D, et al. Relationship between soluble HLA-G and HLA-A,- B,-C serum levels and IFN-gamma production after sublingual immunotherapy in patients with allergic rhinitis. Human Immunol 2008;69:510–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2008.05.010

Cox L, Williams B, Sicherer S, et al. American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Test Task Force, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force. Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing: report from the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;101:580–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60220-7

Malling HJ, Montagut A, Melac M, et al. Eficacy and safety of 5-grass pollen sublingual immunotherapy tablets in patients with different clinical profiles of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:387–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03152.x

Fasce L, Tosca MA, Baroffio M, et al. Atopy in wheezing infants always starts with monosensitization. Allergy Asthma Proc 2007;28:449–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.2500/aap.2007.28.2966

Silvestri M, Rossi GA, Cozzani S, et al. Age-dependent tendency to become sensitized to other classes of aeroallergens in atopic asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999;83:335–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62674-9

Govaere E, van Gysel D, Massa G, et al. The influence of age and gender on sensitization to aero-allergens. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2007;18:671–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00570.x

Silvestri M, Oddera S, Crimi P, et al. Frequency and specific sensitization to inhalant allergens within nuclear families of children with asthma and/or rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1997;79:512–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63058-X

Dykewicz MS, Fineman S, Skoner DP, et al. Diagnosis and management of rhinitis: complete guidelines of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters in Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998;81:478–518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63155-9

Mygind N, Maclerio R . Definition, classification and terminology. In: Mygind NN, ed. Allergic and Non-Allergic Rhinitis. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1993:11–4.

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Osman Mohammed Yusuf

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Funding This study was funded by Artu Biologicals (since 2010 owned by ALK/Abello), Lelystad, The Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CdB, ER, JvdW and HM had full access to the data and were responsible for the conception and design of the study as well as interpretation, analysis and writing. DP, PB and RGvW commented on drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Bot, C., Röder, E., Pols, D. et al. Sensitisation patterns and association with age, gender, and clinical symptoms in children with allergic rhinitis in primary care: a cross-sectional study. Prim Care Respir J 22, 155–160 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00015

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00015

This article is cited by

-

Clinical response to varying pollen exposure in allergic rhinitis in children in The Netherlands

BMC Pediatrics (2023)

-

Gut microbial characteristics of adult patients with allergy rhinitis

Microbial Cell Factories (2020)