Abstract

Since the identification of dystrophin as the protein product of the Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy locus, many different mutations, encompassing the entire spectrum of gene mutations ranging from point mutations to large deletions, have been found. These discoveries have led to the investigation of a variety of methods aimed at the treatment of muscular dystrophy, including strategies for gene replacement, gene correction, and modification of the gene product. The preferred approach in each case depends on the nature of the gene defect. In this Review, we focus on methods that have been developed for gene correction and for the modification of gene products. This mutation-focused approach offers the opportunity for 'personalized' gene therapy for muscular dystrophy and might also be a logical strategy for the treatment of other genetic disorders.

Key Points

-

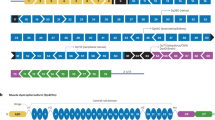

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked recessive disorder of skeletal and cardiac muscle that is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene

-

New approaches to the treatment of DMD are directed at the specific kind of mutation that the patient carries, thereby effectively creating 'personalized gene therapy'

-

Mutation-specific therapies for DMD can be divided broadly into those that focus on point mutations and those that focus on frameshift deletions

-

The main technologies to target point mutations involve small molecules that enable stop-codon suppression, and small oligonucleotides that elicit gene correction

-

The main technology targeted at frameshift deletions is the use of antisense oligonucleotides to induce exon skipping

-

The identification of the patients with DMD who are most likely to benefit from personalized therapy will be greatly enhanced by advances in rapid and accurate molecular diagnostics

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Emery A and Muntoni F (2003) Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, edn 3. New York: Oxford University Press

Nigro G et al. (1983) Prospective study of X-linked progressive muscular dystrophy in Campania. Muscle Nerve 6: 253–262

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM® (2006) Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. OMIM® number: 300376 [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=300376]

Koenig M et al. (1987) Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell 50: 509–517

Hoffman EP et al. (1987) Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 51: 919–928

Ervasti JM and Campbell KP (1991) Membrane organization of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex. Cell 66: 1121–1131

Cohn RD and Campbell KP (2000) Molecular basis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve 23: 1456–1471

Rando TA (2001) The dystrophin-glycoprotein complex, cellular signaling, and the regulation of cell survival in the muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve 24: 1575–1594

Forrest SM et al. (1987) Preferential deletion of exons in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Nature 329: 638–640

Darras BT et al. (1988) Intragenic deletions in 21 Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD)/Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) families studied with the dystrophin cDNA: location of breakpoints on Hind III and BglII exon-containing fragment maps, meiotic and mitotic origin of the mutations. Am J Hum Genet 43: 620–629

Roberts RG et al. (1994) Searching for the 1 in 2,400,000: a review of dystrophin gene point mutations. Hum Mutat 4: 1–11

Prior TW et al. (1995) Spectrum of small mutations in the dystrophin coding region. Am J Hum Genet 57: 22–33

Prior TW and Bridgeman SJ (2005) Experience and strategy for the molecular testing of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Mol Diagn 7: 317–326

Hoffman EP et al. (1988) Characterization of dystrophin in muscle-biopsy specimens from patients with Duchenne's or Becker's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med 318: 1363–1368

Monaco AP et al. (1988) An explanation for the phenotypic differences between patients bearing partial deletions of the DMD locus. Genomics 2: 90–95

Koenig M et al. (1989) The molecular basis for Duchenne versus Becker muscular dystrophy: correlation of severity with type of deletion. Am J Hum Genet 45: 498–506

Baumbach LL et al. (1989) Molecular and clinical correlations of deletions leading to Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Neurology 39: 465–474

Chamberlain JS and Rando TA (2006) Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Advances in Therapeutics. New York: Taylor and Francis

Wolff J et al. (2005) Non-viral approaches for gene transfer. Acta Myol 24: 202–208

Blankinship MJ et al. (2006) Gene therapy strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy utilizing recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Mol Ther 13: 241–249

Liu M et al. (2005) Adeno-associated virus-mediated microdystrophin expression protects young mdx muscle from contraction-induced injury. Mol Ther 11: 245–256

Acsadi G et al. (1991) Human dystrophin expression in mdx mice after intramuscular injection of DNA constructs. Nature 352: 815–818

Danko I et al. (1993) Dystrophin expression improves myofiber survival in mdx muscle following intramuscular plasmid DNA injection. Hum Mol Genet 2: 2055–2061

Scott JM et al. (2002) Viral vectors for gene transfer of micro-, mini-, or full-length dystrophin. Neuromuscul Disord 12 (Suppl 1): S23–S29

Galvez BG et al. (2006) Complete repair of dystrophic skeletal muscle by mesoangioblasts with enhanced migration ability. J Cell Biol 174: 231–243

Fardeau M et al. (2005) About a phase I gene therapy clinical trial with a full-length dystrophin gene-plasmid in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy [French]. J Soc Biol 199: 29–32

Foster K et al. (2006) Gene therapy progress and prospects: Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Gene Ther 13: 1677–1685

Palmer E et al. (1979) Phenotypic suppression of nonsense mutants in yeast by aminoglycoside antibiotics. Nature 277: 148–150

Singh A et al. (1979) Phenotypic suppression and misreading Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 277: 146–148

Martin R et al. (1989) Aminoglycoside suppression at UAG, UAA and UGA codons in Escherichia coli and human tissue culture cells. Mol Gen Genet 217: 411–418

Howard M et al. (1996) Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore CFTR function by overcoming premature stop mutations. Nat Med 2: 467–469

Barton-Davis ER et al. (1999) Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest 104: 375–381

Dunant P et al. (2003) Gentamicin fails to increase dystrophin expression in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Muscle Nerve 27: 624–627

Howard MT et al. (2000) Sequence specificity of aminoglycoside-induced stop condon readthrough: potential implications for treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 48: 164–169

Bidou L et al. (2004) Premature stop codons involved in muscular dystrophies show a broad spectrum of readthrough efficiencies in response to gentamicin treatment. Gene Ther 11: 619–627

Wagner KR et al. (2001) Gentamicin treatment of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy due to nonsense mutations. Ann Neurol 49: 706–711

Politano L et al. (2003) Gentamicin administration in Duchenne patients with premature stop codon: preliminary results. Acta Myol 22: 15–21

Howard MT et al. (2004) Readthrough of dystrophin stop codon mutations induced by aminoglycosides. Ann Neurol 55: 422–426

Arakawa M et al. (2003) Negamycin restores dystrophin expression in skeletal and cardiac muscles of mdx mice. J Biochem (Tokyo) 134: 751–758

Hirawat S et al. (2007) Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of PTC124, a nonaminoglycoside nonsense mutation suppressor, following single- and multiple-dose administration to healthy male and female adult volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 47: 430–444

Welch EM et al. (2007) PTC124 targets genetic disorders caused by nonsense mutations. Nature 447: 87–91

Ye S et al. (1998) Targeted gene correction: a new strategy for molecular medicine. Mol Med Today 4: 431–437

Igoucheva O et al. (2001) Targeted gene correction by small single-stranded oligonucleotides in mammalian cells. Gene Ther 8: 391–399

Gamper HB Jr et al. (2000) A plausible mechanism for gene correction by chimeric oligonucleotides. Biochemistry 39: 5808–5816

Andersen MS et al. (2002) Mechanisms underlying targeted gene correction using chimeric RNA/DNA and single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides. J Mol Med 80: 770–781

Igoucheva O and Yoon K (2000) Targeted single-base correction by RNA–DNA oligonucleotides. Hum Gene Ther 11: 2307–2312

Cole-Strauss A et al. (1996) Correction of the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia by an RNA–DNA oligonucleotide. Science 273: 1386–1389

Rando TA et al. (2000) Rescue of dystrophin expression in mdx mouse muscle by RNA/DNA oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5363–5368

Bartlett RJ et al. (2000) In vivo targeted repair of a point mutation in the canine dystrophin gene by a chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotide. Nat Biotechnol 18: 615–622

Bertoni C et al. (2006) Enhanced level of gene correction mediated by oligonucleotides containing CpG modification in the mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy [abstract #573]. Presented at the 9th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Gene Therapy: 2006 May 31–June 4, Baltimore, MD, USA

Schwartz TR and Kmiec EB (2007) Reduction of gene repair by selenomethionine with the use of single-stranded oligonucleotides. BMC Mol Biol 8: 7

Parekh-Olmedo H et al. (2001) Targeted gene repair in mammalian cells using chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides and modified single-stranded vectors. Sci STKE 2001: PL1

Bertoni C et al. (2005) Strand bias in oligonucleotide-mediated dystrophin gene editing. Hum Mol Genet 14: 221–233

Igoucheva O et al. (2006) Involvement of ERCC1/XPF and XPG in oligodeoxynucleotide-directed gene modification. Oligonucleotides 16: 94–104

Schmalbruch H and Lewis DM (2000) Dynamics of nuclei of muscle fibers and connective tissue cells in normal and denervated rat muscles. Muscle Nerve 23: 617–626

McLoon LK et al. (2004) Continuous myofiber remodeling in uninjured extraocular myofibers: myonuclear turnover and evidence for apoptosis. Muscle Nerve 29: 707–715

Bertoni C and Rando TA (2002) Dystrophin gene repair in mdx muscle precursor cells in vitro and in vivo mediated by RNA–DNA chimeric oligonucleotides. Hum Gene Ther 13: 707–718

Aartsma-Rus A et al. (2006) Entries in the Leiden Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutation database: an overview of mutation types and paradoxical cases that confirm the reading-frame rule. Muscle Nerve 34: 135–144

Dominski Z and Kole R (1993) Restoration of correct splicing in thalassemic pre-mRNA by antisense oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 8673–8677

Vacek M et al. (2003) Antisense-mediated redirection of mRNA splicing. Cell Mol Life Sci 60: 825–833

van Deutekom JC et al. (2001) Antisense-induced exon skipping restores dystrophin expression in DMD patient derived muscle cells. Hum Mol Genet 10: 1547–1554

Aartsma-Rus A et al. (2003) Therapeutic antisense-induced exon skipping in cultured muscle cells from six different DMD patients. Hum Mol Genet 12: 907–914

McClorey G et al. (2006) Induced dystrophin exon skipping in human muscle explants. Neuromuscul Disord 16: 583–590

Wilton SD et al. (1999) Specific removal of the nonsense mutation from the mdx dystrophin mRNA using antisense oligonucleotides. Neuromuscul Disord 9: 330–338

Fall AM et al. (2006) Induction of revertant fibres in the mdx mouse using antisense oligonucleotides. Genet Vaccines Ther 4: 3

Lu QL et al. (2003) Functional amounts of dystrophin produced by skipping the mutated exon in the mdx dystrophic mouse. Nat Med 9: 1009–1014

Gebski BL et al. (2003) Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide induced dystrophin exon 23 skipping in mdx mouse muscle. Hum Mol Genet 12: 1801–1811

Fletcher S et al. (2006) Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse after localised and systemic administration of a morpholino antisense oligonucleotide. J Gene Med 8: 207–216

Alter J et al. (2006) Systemic delivery of morpholino oligonucleotide restores dystrophin expression bodywide and improves dystrophic pathology. Nat Med 12: 175–177

Sirsi SR et al. (2005) Poly(ethylene imine)-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymers facilitate efficient delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to nuclei of mature muscle cells of mdx mice. Hum Gene Ther 16: 1307–1317

Williams JH et al. (2006) Induction of dystrophin expression by exon skipping in mdx mice following intramuscular injection of antisense oligonucleotides complexed with PEG–PEI copolymers. Mol Ther 14: 88–96

Fletcher S et al. (2007) Morpholino oligomer-mediated exon skipping averts the onset of dystrophic pathology in the mdx mouse. Mol Ther 15: 1587–1592

Goyenvalle A et al. (2004) Rescue of dystrophic muscle through U7 snRNA-mediated exon skipping. Science 306: 1796–1799

Denti MA et al. (2006) Body-wide gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3758–3763

Takeshima Y et al. (2006) Intravenous infusion of an antisense oligonucleotide results in exon skipping in muscle dystrophin mRNA of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Res 59: 690–694

van Deutekom et al. (2007) Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med 357: 2677–2686

Aartsma-Rus A et al. (2002) Targeted exon skipping as a potential gene correction therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 12 (Suppl 1): S71–S77

Beroud C et al. (2007) Multiexon skipping leading to an artificial DMD protein lacking amino acids from exons 45 through 55 could rescue up to 63% of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mutat 28: 196–202

Aartsma-Rus A et al. (2004) Antisense-induced multiexon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy makes more sense. Am J Hum Genet 74: 83–92

Bertoni C and Rando TA (2002) Dystrophin gene repair in mdx muscle precursor cells in vitro and in vivo mediated by RNA–DNA chimeric oligonucleotides. Hum Gene Ther 13: 707–718

Wilton SD et al. (1997) Dystrophin gene transcripts skipping the mdx mutation. Muscle Nerve 20: 728–734

Lu QL et al. (2000) Massive idiosyncratic exon skipping corrects the nonsense mutation in dystrophic mouse muscle and produces functional revertant fibers by clonal expansion. J Cell Biol 148: 985–996

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, L., Rando, T. Technology Insight: therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy—an opportunity for personalized medicine?. Nat Rev Neurol 4, 149–158 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpneuro0737

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpneuro0737

This article is cited by

-

Transgenic primate offspring

Nature (2009)

-

A novel custom high density-comparative genomic hybridization array detects common rearrangements as well as deep intronic mutations in dystrophinopathies

BMC Genomics (2008)

-

Follow the follistatin

Science-Business eXchange (2008)