Abstract

This study sought to assess blood pressure (BP) control rates by determining the factors associated with poor BP control, therapeutic management and physicians’ therapeutic behavior among elderly Spanish hypertensive patients in a primary care setting. This cross-sectional multicenter study included hypertensive patients at least 80 years of age in primary care settings throughout Spain who were on pharmacologic treatment. BP was considered well controlled at <140/90 mm Hg (<130/80 in patients with diabetes, chronic renal disease or cardiovascular disease). A total of 923 patients were included (83.3±3.5 years; 62.9% women). Almost two-thirds (64.0%) of the patients were taking a combined therapy (68.7%; 2 drugs) and approximately one-third (35.6%; 95% CI 32.6–38.7) of the patients attained BP goals. Physicians modified the antihypertensive treatment in 26.1% (95% CI 22.3–29.9) of patients with uncontrolled BP, which most frequently involved the addition of another drug (47.6%). Predictive factors for no BP control and no therapeutic modification in patients with uncontrolled BP included diabetes (OR 2.8 (95% CI 2.0–3.9); P<0.0001) and mistaken physician perceptions about BP control (OR 108.1 (95% CI 40.5–288.6); P<0.0001), respectively. Only three out of 10 hypertensive patients 80 years or older in Spain achieved the BP goals. Physicians only modified the treatment in one out of four patients with uncontrolled BP. Diabetes was associated with a threefold increase in the likelihood of uncontrolled BP, and the mistaken physician perceptions about BP control were associated with a 100-fold rise in the probability of not modifying antihypertensive therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular morbidity and health costs are increasing among the elderly in the majority of Western countries, owing primarily to the aging of the population.1, 2 In Spain, the proportion of patients 80 years or older has increased by 28.8% in the past 6 years, and it has been estimated that this percentage will rise by about 33% by 2015 and 44% by 2020.3

Hypertension is one of the most important factors for cardiovascular risk. Although the prevalence of hypertension increases with age (about three-quarters of patients 80 years or older are hypertensives), the available evidence about the benefits of treating hypertension in that patient population is scarce.4, 5 Most randomized controlled trials involving older adults either have excluded those 80 years or older or have included too few participants.6, 7, 8, 9

Systolic blood pressure (BP) increases with age, whereas diastolic pressure rises until the 50 s and falls after that.10 Taking into account that the majority of patients with hypertension are above that age, it has been suggested that only systolic BP should be considered a target in the elderly population.11

The results of the HYVET trial have just been published. In that study, 3845 patients from Europe, China, Australasia and Tunisia who were 80 years old or older and had a sustained systolic BP of ⩾160 mm Hg were randomly assigned to receive antihypertensive treatment (vs. placebo) with a target BP of 150/80 mm Hg. Active treatment was associated with a 30% reduction in the rate of fatal or nonfatal stroke, a 39% reduction in the rate of death from stroke, a 21% reduction in the rate of death from any cause, a 23% reduction in the rate of death from cardiovascular causes and a 64% reduction in the rate of heart failure, with fewer serious adverse events.12 The results of this trial strongly suggest that in hypertensive patients 80 years or older, achieving BP goals is crucial to improved cardiovascular prognosis. However, physicians and patients remain largely unaware of this. Indeed, scarce information exists for this patient population with regard to clinical profiles, therapeutic management and BP control rates.13, 14

This study sought to assess BP control rates by determining which factors were associated with poor BP control, therapeutic management and physicians’ therapeutic behavior among elderly Spanish hypertensive patients in a primary care setting.

Methods

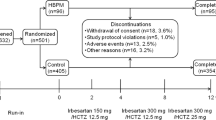

PRESCAP 2006 was a multicenter and cross-sectional survey that aimed at determining the BP control rates in hypertensive patients in a primary care setting.15 This paper presents the results regarding patients 80 years or older. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital La Paz, Madrid, and the patients were provided with written informed consent documents before enrollment.

A total of 2850 general practitioners throughout Spain participated in the study, which was conducted for 3 days (20 June 2006 to 22 June 2006). Each investigator was asked to include the first four consecutive outpatients at the clinic who met the inclusion criteria. Patients of both sexes, at least 18-years old and with an established diagnosis of hypertension, were included in the study. Hypertension was considered when patients had a systolic BP of 140 mm Hg, diastolic BP of 90 mm Hg (130/80 mm Hg for diabetics) or a history of hypertension and taking antihypertensive medication. Patients with a recent diagnosis of hypertension (<6 months) or those undergoing treatment for <3 months were excluded. Overall, 11 094 patients with hypertension were included; a total of 574 patients were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or because incorrect data were recorded. In total, 10 520 patients were analyzed. Of these, 923 patients (8.8%) were 80 years or older.

The biodemographic data, risk factors, and history of cardiovascular disease and treatments, which were defined according to the 2003 European Guidelines,16 were recorded for every patient. Ischemic heart disease was defined as the presence of angina, evidence of myocardial ischemia assessed by stress tests, history of myocardial infarction or previous revascularization (surgery or percutaneous). The presence of organ damage (left ventricular hypertrophy) or associated clinical conditions (heart failure, peripheral artery disease, renal impairment and stroke) was recorded from the clinical history of the patient. The diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy was established by either electrocardiogram or echocardiogram according to the definition of the 2003 European Guidelines.16 Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol >6.5 mmol l−1 (250 mg per 100 ml), LDL cholesterol >4.0 mmol l−1 (150 mg per 100 ml), HDL cholesterol <1.0 and 1.2 mmol l−1 (40 and 48 mg per 100 ml) in men and women, respectively, or triglycerides >1.7 mmol l−1 (150 mg per 100 ml). Smoking was defined as current smokers of ⩾1 cigarette per day in the last month. Excessive alcohol intake was considered weekly consumption equivalent to 26 oz of 40-proof alcohol. A sedentary lifestyle was defined as daily physical activity of less than a 30-min walk. Waist circumference was measured at the midway point between the iliac crest and the costal margin. Obesity was defined as body mass index of ⩾30 kg m−2, and abdominal obesity was defined as waist circumference of >102 and 88 cm in men and women, respectively.

Blood pressure readings were taken according to the 2003 European Guidelines, with the patients in a seated position with their backs supported and after a 5 min rest, using calibrated aneroid or mercury sphygmomanometers or validated automatic devices, depending on the availability.16 The patients were advised to avoid smoking or drinking coffee within 30 min of BP assessment. The visit BP was the average of two separate measurements taken by the examining physician, and a third measure was obtained when there was a difference of ⩾5 mm Hg between the two readings. Adequate BP control was defined as the systolic BP of <140 mm Hg and diastolic BP of <90 mm Hg (<130 and <80 mm Hg for diabetics, chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease).16 The type, number and time of taking of antihypertensive agents were recorded. As this survey was conducted to represent daily clinical practice, patients were not asked earlier to take their antihypertensive treatment. After BP measurement, physicians were asked whether they considered their patients to have adequate BP control and whether they would recommend any change in antihypertensive therapy, and, if so, what change and why.

Statistical analysis

The presence of normal distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables, which were expressed as means (s.d.), were compared using Student's t-test for paired and unpaired data. Categorical variables, expressed as a percentage, were compared using the χ2-test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. To determine the main factors involved in BP control and in the therapeutic behavior of the physicians, a multivariate analysis was performed. Cardiovascular risk factors, including abdominal obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular and renal diseases, time of evolution of hypertension (⩽5 vs. >5 years), antihypertensive drugs, whether the patient had taken the treatment on the day of the visit, the time of the visit and the perception of physicians about BP control of patients were included as potential predictive factors. The data design was subjected to internal consistency rules and ranges to control for inconsistencies/inaccuracies in the collection and tabulation of data. Statistical significance was set at a P-value <0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS statistics package, version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Biodemographic data

A total of 923 patients (62. 9% women; 83.3±3.5 years) were included in the study. The mean time of evolution of hypertension was 13.2±8.7 years; 680 participants (73.7%) were 80–84 years of age, 177 (19.2%) were 85–89 years of age and 66 (7.1%) were ⩾90 years of age. The main clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The three most frequent cardiovascular risk factors were sedentary lifestyle (66.7%), abdominal obesity (47.1%) and dyslipidemia (44.5%). With regard to organ damage and vascular disease, 11.2% of the patients showed left ventricular hypertrophy and 42.4% cardiovascular disease (15.8% renal failure, 14.0% coronary heart disease, 13.9% heart failure, 6.8% stroke, 5.9% peripheral artery disease and 2.4% advanced retinopathy). Women were older (83.4±3.5 vs. 83.1±3.6 years) and showed a higher body mass index (28.6±4.6 vs. 28.3±3.7 kg m−2), whereas men had a larger waist circumference (98.5±13.4 vs. 94.9±14.9 cm; all P=0.001). The prevalence of a sedentary lifestyle (67.0% vs. 33.0%; P<0.001), abdominal obesity (74.4 vs. 25.6%; P<0.001) and cardiovascular disease (58.0 vs. 42.0%; P=0.004) was higher in women than in men, whereas smoking showed the opposite trend (88.3 vs. 11.7%; P<0.0001).

Hypertension and BP control rates

The mean BP was 139.7±15.8/77.0±9.5 mm Hg, with no significant differences between genders (138.8±14.6/77.2±10.0 in men and 140.2±16.4/76.9±9.3 mm Hg in women); 29.5% (95% CI 26.5–32.4%) showed a high-normal BP. The distribution of patients according to the different 2003 ESH/ESC BP categories is presented in Table 2.

A total of 35.6% of patients achieved BP goals; 39.2% showed control of only systolic BP and 72.3% showed control of only diastolic BP; no significant differences were found between genders: 34.1%, 36.9% and 69.2%, respectively, in men vs. 36.8%, 40.8% and 73.6%, respectively, in women (Table 3).

An additional analysis was performed to determine whether there were differences in BP control regarding the three age groups: 80–84 years, 85–89 years and ⩾90 years. BP control rates were 35.9%, 34.5% and 36.4% for patients in the three age groups, respectively (P=NS). BP control rates were poorer in patients with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and kidney disease (18.2% vs. 43.1%, P<0.001; 30.7% vs. 40.2%, P<0.05 and 27.9% vs. 37.3%, P<0.01, respectively). Patients with uncontrolled BP had more dyslipidemia and organ damage, and were more frequently diabetic. A total of 12.9% (n=119) did not take medication on the day of the visit. There was better BP control among patients who had taken antihypertensive medication on the day of the visit (90.7% vs. 9.3%, P=0.018).

Antihypertensive treatment

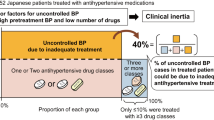

The mean time of treatment was 11.2±7.5 years, 10.5±7.3 years in men vs. 11.7±7.6 years in women, P<0.05. Of the patients, 36.0% (n=332) were on monotherapy and the other 64.0% (n=591) were on combined therapy (68.7% (n=406) were on two drugs and 31.3% (n=185) on three or more agents). When considering each antihypertensive drug individually, 30.7% (n=283) of the patients were taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), 28.9% (n=267) angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and 21.4% (n=198) diuretics (Figure 1). Regarding combined therapy, overall, fixed combinations were prescribed in 28.1% (n=259) of the patients (ACEi diuretic (43.4%, n=113), ARB (35.6%, n=92), ACEi calcium channel blocker (12.8%, n=33), β-blocker-diuretic (6.1%, n=16) and others (2.1%, n=5)) and free combinations were prescribed in 35.9% (n=332) of the patients (ACEi diuretic (27.9%, n=93), ARB diuretic (23.7%, n=79), ACEi-calcium channel blocker (10.3%, n=34), ACEi-β-blocker (8.1%, n=27), diuretic calcium channel blocker (6.1%, n=20), diuretic-β-blocker (5.8%, n=19), ARB-ACEi (5.3%, n=18), ARB-β-blocker (3.9%, n=13) and others (8.9%, n=29)). No significant differences were found between BP control rates and being on monotherapy (36.7%) or combined therapy (35.0%).

Physicians’ therapeutic behavior and insufficient BP control

Physicians modified antihypertensive treatment in 26.1% (95% CI 22.3–29.9%) of the patients with uncontrolled BP. The causes for therapy modification were lack of efficacy (89.5%), side effects (6.3%) and others (4.2%). In 47.6% of the cases, another antihypertensive drug was added; in 34.1% of the cases, the dose of the earlier antihypertensive agent was increased; in 4.9% of the cases, the earlier medication was substituted by another; and in 13.4% of the cases, another action was performed. When compared with patients <80 years old, the frequency of treatment modification by physicians was higher in younger patients (31.2% (95% CI 30.0–32.5%), P=0.04), Figure 2. No differences were found between genders regarding the behavior of the physicians.

With regard to the physicians’ perception of patients’ BP control, 60.0% of the patients with uncontrolled BP were considered well controlled. Of these, 85.2% had taken their medication on the day of the visit. Their BP values were 139.9±8.9 and 77.6±8.6 mm Hg. In those patients whose BP was considered uncontrolled, general practitioners modified the treatments in 89.1% vs. 10.9% of patients who were considered well controlled (P<0.0001).

The predictive factors most frequently associated with no BP control and with no therapeutic modification in patients with uncontrolled BP were diabetes (OR 2.8 (95% CI 2.0–3.9); P<0.0001) and the physicians' wrong perceptions of patients’ BP control (OR 108.1 (95% CI 40.5–288.6); P<0.0001), respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

Different guidelines have reported that the presence of hypertension increases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality; even small elevations above the optimal BP values increase the likelihood of developing negative cardiovascular outcomes.16, 17, 18 Taking into account that some epidemiological studies have suggested that BP is inversely related to the risk of death in patients 80 years or older, there is very scarce information about the best practices in the elderly population.4, 19, 20 However, recent clinical trials such as HYVET12 provide consistent evidence that antihypertensive treatment in persons 80 years of age or older is beneficial. In this context, surveys such as PRESCAP 2006 are important because they depict clinical practice and provide an accurate picture of the hypertensive population 80 years of age or older who are managed in primary care. This is a common condition. In fact, our study indicated that about 9% of the patients who are attended to daily in primary care settings are 80 years of age or older. Concomitant cardiovascular risk factors such as organ damage and vascular disease are common in this overall study population and in other studies conducted under conditions common to daily clinical practice.19, 21

In our study, 35.6% of the patients who were 80 years or older achieved BP goals vs. 41.4% of the overall study population.15 Similarly, in two studies conducted in the United States and Europe,22, 23 BP control declined with advancing age. Although BP control is still far from optimal, in recent years, BP control has improved not only in the general population but also in the elderly and high-risk subgroups.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Interestingly, BP control improved in patients ⩾90 years old (36.4%). This could be explained by the fact that systolic BP declines after 85 years and because it is more likely that patients with poorer BP control would have died from this or other causes.14, 19 In multivariate analysis, diabetes (OR 2.8) and not having taken the medication on the day of the visit (OR 1.7) were predictors of no BP control. Although significant in other studies, predictors from other surveys such as gender or body mass index were not significant in our study.19, 26 This could be related to the fact that gender differences and muscle mass decrease with age.29

About two-third of the study population was taking two or more drugs. The median number of antihypertensive agents was 2 (range 1–6). Although this is positive, our study showed that only about one-quarter of physicians modified antihypertensive treatment in patients with uncontrolled BP, with lack of efficacy being the most frequent reason. Mistaken physician perceptions about BP control for their patients dramatically increased (OR 108.1) the probability of not making changes in the antihypertensive treatment of participants with uncontrolled BP. Unfortunately, this occurs not only in the elderly but also in the overall hypertensive population.29 It has been suggested that an incorrect perception of BP control may be one of the most important factors for therapeutic inertia.30 It is likely that some physicians may be afraid of prescribing two or more antihypertensive drugs in this population to avoid side effects and polymedication.29 Taking into account that 60% of the patients with uncontrolled BP were perceived as well controlled, it is necessary to carry out medical education activities to improve the maintenance of good BP control in very elderly hypertensive patients. On the other hand, when the perception of uncontrolled BP was correct, nearly 90% of the physicians modified the treatment.

Limitations

As the patients and physicians were not randomly selected and as BP control was calculated with 2–3 office measurements in the same visit, it is likely that these data cannot be generalized to the whole Spanish population. Moreover, as our study was carried out in a population attended by general practitioners in Spain, the data could probably only be generalized to countries with similar health care delivery and cardiovascular risk profiles. As the aim of this study was to investigate BP control in the hypertensive population of 80 years of age or older under conditions of daily clinical practice, the high number of participants and meticulousness of data collection make the results representative for this population. This cross-sectional survey was conducted in 2006. Taking into account that the HYVET research was published in 2008, there has been little time for physicians to enact behavior change, and it is likely that the results of this study may still represent current clinical practice.

Conclusions

Only three out of 10 hypertensive patients of 80 years of age or older in Spain achieve BP goals. Physicians only modify treatment in one of the four patients with uncontrolled BP. Diabetes is associated with a threefold increase in the likelihood of bad BP control and mistaken physician perceptions of BP control with a 100-fold rise in the probability of not modifying the antihypertensive therapy.

Addendum

Members of the working group of arterial hypertension of SEMERGEN

T Sánchez-Ruiz (Valencia), JL Llisterri-Caro (Valencia), GC Rodríguez-Roca (La Puebla de Montalbán, Toledo), FJ Alonso-Moreno (Toledo), S Lou-Arnal (Utebo, Zaragoza), JA Divisón-Garrote (Casas Ibáñez, Albacete), JA Santos-Rodríguez (Rianxo, A Coruña), O García-Vallejo (Madrid), LM Artigao-Rodenas (Albacete), R Durá-Belinchón (Burjassot, Valencia), M Ferreiro-Madueño (Sevilla), E Carrasco-Carrasco (Abarán, Murcia), T Rama-Martínez (Badalona, Barcelona), P Beato-Fernández (Badalona, Barcelona), JJ Mediavilla-Bravo (Pampliega, Burgos), MA Pérez-Llamas (Boiro, A Coruña), I Mabe-Angulo (Getxo, Bizkaia), JL Carrasco-Martín (Estepona, Málaga), JM Fernández-Toro (Cáceres), L García-Matarín (Vícar, Almería), MA Prieto-Díaz (Oviedo, Asturias), JL Górriz-Teruel (Valencia), V Barrios-Alonso (Madrid), A Calderón-Montero (Madrid), A González-Sánchez (Teguise, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), JC Martí-Canales (Motril, Granada), V Pallarés-Carratalá (Castellón), J Polo-García (Cáceres), F Valls-Roca (Benigànim, Valencia), A Galgo-Nafría (Madrid).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Ezzati M, Hoorn SV, Rodgers A, Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Murray CJ . The Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Estimates of global and regional potential health gains from reducing multiple major risk factors. Lancet 2003; 362: 271–280.

Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould L, Hofman KJ . The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA 2004; 291: 2616–2622.

National institute of statistics. Estimates of the current population of Spain calculated from the 2001 census: population by reference date, sex and age group Inebase. Available at http://www.ine.es/jaxi/tabla.do?per=12&type=db&divi=epob&idtab=1.

Rastas S, Pirttilä T, Viramo P, Verkkoniemi A, Halonen P, Juva K, Niinistö L, Mattila K, Länsimies E, Sulkava R . Association between blood pressure and survival over 9 years in a general population aged 85 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 912–918.

Satish S, Freeman Jr DH, Ray L, Goodwin JS . The relationship between blood pressure and mortality in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 367–374.

MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ 1992; 304: 405–412.

Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Scherstén B, Ekbom T, Wester PO . Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOPHypertension). Lancet 1991; 338: 1281–1285.

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991; 265: 3255–3264.

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhäger WH, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Dollery CT, Fletcher AE, Forette F, Leonetti G, Nachev C, O’Brien ET, Rosenfeld J, Rodicio JL, Tuomilehto J, Zanchetti A . Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet 1997; 350: 757–764.

Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, L’Italien GJ, Lapeurta P . Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Hypertension 2001; 37: 869–874.

Williams B, Lindholm LH, Sever P . Systolic pressure is all that matters. Lancet 2008; 371: 2219–2221.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C, Belhani A, Forette F, Rajkumar C, Thijs L, Banya W, Bulpitt CJ, HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1887–1898.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D . Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum. Current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA 2005; 294: 466–472.

Franklin SS, Gustin W, Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB, Levy D . Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1997; 96: 308–315.

Llisterri-Caro JL, Rodríguez-Roca GC, Alonso-Moreno FJ, Banegas-Banegas JR, González-Segura D, Lou-Arnal S, Divisón-Garrote JA, Sánchez-Ruiz T, Santos-Rodríguez JA, Barrios-Alonso V . Control of blood pressure in Spanish hypertensive population attended in primary health-care. PRESCAP 2006 Study. Med Clin (Barc) 2008; 130: 681–687.

European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 1011–1053.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright Jr JT, Roccella EJ . The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention: Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289: 2560–2572.

Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Narkiewicz K, Ruilope L, Rynkiewicz A, Schmieder RE, Boudier HA, Zanchetti A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Erdine S, Kiowski W, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Lindholm LH, Viigimaa M, Adamopoulos S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Bertomeu V, Clement D, Erdine S, Farsang C, Gaita D, Lip G, Mallion JM, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, O’Brien E, Ponikowski P, Redon J, Ruschitzka F, Tamargo J, van Zwieten P, Waeber B, Williams B . 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: the task force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1105–1187.

Rodríguez-Roca GC, Artigao-Rodenas LM, Llisterri-Caro JL, Alonso Moreno FJ, Banegas Banegas JR, Lou Arnal S, Pérez Llamas M, Raber Béjah A, Pacheco López R . Control of hypertension in elderly patients receiving primary care in Spain. Rev Esp Cardiol 2005; 58: 359–366.

Langer RD, Criqui MH, Barrett-Connor EL, Klauber MR, Ganiats TG . Blood pressure change and survival after age 75. Hypertension 1993; 22: 551–559.

Barrios V, Escobar C, Calderón A, Llisterri JL, Echarri R, Alegría E, Muñiz J, Matalí A . Blood pressure and lipid goal attainment in the hypertensive population in the primary care setting in Spain. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007; 9: 324–329.

Wyatt SB, Akylbekova EL, Wofford MR, Coady SA, Walker ER, Andrew ME, Keahey WJ, Taylor HA, Jones DW . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension 2008; 51: 650–656.

van Rossum CTM, van de Mheen H, Witteman JCM, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Grobbee DE . Prevalence, treatment and control of hypertension by sociodemographic factors among the Dutch elderly. Hypertension 2000; 35: 814–821.

González-Juanatey JR, Alegría E, Lozano JV, Llisterri JL, García JM, González I . Impact of hypertension in cardiac diseases in Spain. The CARDIOTENS Study 1999. Rev Esp Cardiol 2001; 54: 139–149.

Banegas JR, Segura J, Ruilope LM, Luque M, García-Robles R, Campo C, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Tamargo J, CLUE Study Group Investigators. Blood pressure control and physician management of hypertension in hospital hypertension units in Spain. Hypertension 2004; 43: 1338–1344.

Ong KL, Cheung BMY, Man YB, Lam KSL . Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension 2007; 49: 69–75.

Whitmer RA, Gustafson DR, Barrett-Connor E, Haan MN, Gunderson EP, Yaffe K . Central obesity and increased risk of dementia more than three decades later. Neurology 2008; 71: 1057–1064.

Wolf-Maier K, Cooper R, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, Kastarinen M, Poulter N, Primatesta P, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Stegmayr B, Thamm M, Tuomilehto J, Vanuzzo D, Vescio F . Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada and the United States. JAMA 2003; 289: 2363–2369.

Schmieder RE, Ruilope LM . Blood pressure control in patients with comorbidities. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008; 10: 624–631.

Barrios V, Escobar C, Bertomeu V, Murga N, de Pablo C, Calderón A . Importance of perception for blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1928.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all the investigators who have actively participated in this study. Without their dedication and quality of work, this publication would not have been possible. We also thank Almirall, S.A. pharmaceuticals for its financial support and ADKNOMA HEALTH RESEARCH S.L. for statistical analyses, both indispensable to complete this observational study. All data have been recorded and analyzed independently to prevent bias.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Roca, G., Pallarés-Carratalá, V., Alonso-Moreno, F. et al. Blood pressure control and physicians’ therapeutic behavior in a very elderly Spanish hypertensive population. Hypertens Res 32, 753–758 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.102

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.102

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypertension in older patients, a retrospective cohort study

BMC Geriatrics (2016)

-

Blood pressure control and management of very elderly patients with hypertension in primary care settings in Spain

Hypertension Research (2014)

-

Treatment of hypertension in the elderly: data from an international cohort of hypertensives treated by cardiologists

Journal of Human Hypertension (2013)