Abstract

Aims

The instillation of a combined flourescein-anaesthetic eye drop is common practice in most ophthalmology clinics. Chauvin Pharmaceuticals produce unpreserved proxymethacaine 0.5% and flourescein 0.25% in a Minims® vial (PFM) intended for single application only. Our aim was to determine whether the reuse of these eye drops for multiple applications has the potential for bacterial transmission.

Methods

Samples were collected from doctors in general outpatient clinics. Each sample constituted a blood agar plate inoculated with the initial drop of fluid from a PFM as a control. The vial was then used for multiple applications on consecutive patients. One of the last remaining drops was then inoculated onto an alternate marked site on the same plate to serve as the test sample. The samples were immediately transported to the Microbiology laboratory and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The results were interpreted thereafter by a Microbiologist.

Results

A total of 41 samples were collected by eight Samplers. In all, 7/41(17%) samples showed growth of normal conjunctiva and lid flora on the test area. These were coagulase negative Staphylococciand Corynebacteriumspp.

Conclusions

The reuse of single application of PFM should be questioned due to the potential risk of transmitting pathogens. A change to a single use only policy would result in a projected threefold increase in the annual budget for these drops.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The instillation of a combined fluorescein-anaesthetic eye drop has become common practice in most ophthalmology clinics. This facilitates Goldmann applanation tonometry for determining intraocular pressure and corneal staining to elucidate any epithelial defect.

In the United Kingdom, Chauvin Pharmaceuticals (a subsidiary of Bausch & Lomb), produce individual vials of various eye drops called Minims, intended for a single application only. Each vial contains 0.5 ml of solution. Each drop delivered is approximately 50 μl (0.05 ml), which equates to about 10 drops per vial.

Discarding 80% of the medication and the entire packaging after an intended single application does appear to be wasteful and not cost effective. An audit of the current practice of 62 UK Ophthalmologists revealed that 79% reused Minims vials on more than one patient during the course of their routine practice.

The risk associated with multiple applications is the transmission of micro-organisms between eyes by a contaminated vial. Precautionary measures employed to reduce this risk are hand washing, alcohol hand gels, avoidance of contact with the eye or lids, discarding any possibly contaminated vial, recapping the vial after use, and excluding all possibly infected eyes from the chain of multiple applications. Various studies have shown contamination of multiuse ophthalmic solutions and their applicators.1, 2, 3 There is, however, little evidence that accurately assesses the safety of using Minims vials for multiple applications.

Our aim was to determine whether the commonly followed practice of using single application Minims eye drops for multiple applications during a single clinic session has the potential for bacterial transmission.

Materials and methods

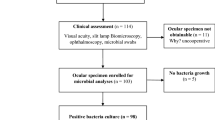

Ethical approval was deemed not to be required by the local Research and Ethics Committee for this prospective non-randomised series. Samples were collected randomly from doctors in general outpatient clinics over a 2-week period. Each sample constituted a blood agar plate, which was inoculated on a marked site with an initial drop (applied immediately upon opening the vial) of fluid from a combined proxymethacaine 0.5% and fluorescein 0.25% unpreserved Minim (PFM) vial as a control. The vial was then used for multiple applications on consecutive patients taking all the previously mentioned precautionary measures. One of the last remaining drops was then inoculated onto an alternate marked site on the same plate to serve as the test sample. The sampler and the number of patients the vial was used on were recorded. To be included in the study, the same vial needed to be used for the control, consecutive patients, and the test sample. All patients with active ocular infection and samples with a high risk of contamination (eg, vials making contact with the lids) were excluded. The samples were immediately transported to the Microbiology laboratory and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The results were interpreted thereafter by the same consultant microbiologist. The primary outcome measure was the culture results.

Results

A total of 41 samples were collected by eight samplers. The number of samples submitted by each doctor ranged from 1 to 11 (mean 5.12, SD 3.68).

The vials were used on 196 patients (392 eyes) in total. The number of patients per culture plate ranged from 1 to 7 (mean 4.78, SD 1.56).

None of Minims vials showed bacterial growth on the control drop. In all, 7 of the 41 samples were positive for normal conjunctiva and lid flora on the test area (these results are summarised in Table 1.)

These were coagulase negative Staphylococci and Corynebacterium spp. Therefore, 17% of the samples were contaminated after routine use. Figure 1 shows a positive culture.

Discussion

Our study suggests that the practice of reusing PFMs has the potential for bacterial transmission, despite employing precautionary measures. It would be logical to assume that the same should apply for various other micro-organisms including viruses. Inter ocular viral transmission through direct contact with ocular secretions is a well-known phenomenon. Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis is a common example. In cases where there is obvious ocular infection, preventative measures can be taken to prevent cross contamination. Viral infection may, however, not be apparent and transmission may have much more grave consequences. HSV-1, VZV, CMV, EBV, Hepatitis B and C, and HIV among others have all been shown to appear in the tear film of infected patients. Therefore, the potential exists for inter ocular transmission.

There is little robust evidence to compare our results. The contamination of the vial nozzle as expected and, to a lesser degree, the content (which was not precisely quantified) has been shown in a similar study.4 Contact with the nozzle could cause transmission directly or indirectly by contaminating a passing drop. If no direct contact with any part of the eye takes place, as intended, it would be more valid to culture a drop as this mimics the natural course of events.

There are obviously significant cost implications associated with this suggested practice. A box containing 20 Minims costs our trust £8.30 that equates to 41.5p per vial. In March 2007, the price quoted in the BNF was £7.95.5

The NHS Hospital Episode Statistics for 2005–20006 financial year revealed that 5 120 671 patients (ie, 10.23% of all outpatient consults) were seen in Ophthalmology outpatients within the NHS in England.6 Assuming 80% of Ophthalmologists do reuse the Minims®, as suggested by a recent audit,4 the cost incurred would be £765 028 (this is a conservative estimate assuming that each vial is used on five patients, and does not allow for any wastage).

If a new Minims was used on each of the total number of patients, the cost to the NHS would be £2 125 079. This equates to an almost threefold additional cost of £ 1 360 050 to the NHS across England.

The cost effectiveness of adopting our suggested practice is not known. We have not audited the exact number of patients presenting with conjunctivitis post-eye clinic examination, but after questioning all primary care nurses and doctors, this number appears to be very low. What about asymptomatic patients who may have contracted a virus that presents later or may not cause any ocular involvement? What are the possible clinical sequelae that may result? Is reducing cross contamination in a small number of patients cost effective when weighted against the enormous potential cost of implementing a strategy of single use?

The cost of a PFM is about 1% of the cost of a single outpatient attendance.

In the interest of patient safety, our study suggests using PFM for a single application only.

References

Nentwich MM, Kollmann KH, Meshack J, Ilako DR, Schaller UC . Microbial contamination of multi-use ophthalmic solutions in Kenya. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 1265–1268.

Jokl DH, Wormser GP, Nichols NS, Montecalvo MA . Karmen CL Bacterial contamination of ophthalmic solutions used in an extended care facility. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 1308–1310.

Rahman MQ, Tejwani D, Wilson JA, Butcher I . Ramaesh K Microbial contamination of preservative free eye drops in multiple application containers. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 139–141.

Qureshi MA, Wong R, Robbie SJ, Qureshi KM, Rowe C, Leach J . Contamination of single-use Minims eye drops by multiple use in clinics. J Hosp Infect 2006; 62: 245–247.

Mehta DK . British National Formulary (BNF) 54. Pharmaceutical Press: UK, 2007, p 564.

Department of Health. Hospital Episode Statistics online NHS England, 2007, http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=893.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

There were no competing and financial interests for this project

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rautenbach, P., Wilson, A. & Gouws, P. The reuse of opthalmic minims®: an unacceptable cross-infection risk?. Eye 24, 50–52 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.39