Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the long-term effectiveness and safety of botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT-A) treatment in patients with blepharospasm (BEB), hemifacial spasm (HFS), and entropion (EN) and to use for the first time two modified indexes, ‘botulin toxin escalation index-U’ (BEI-U) and ‘botulin toxin escalation index percentage’ (BEI-%), in the dose-escalation evaluation.

Methods

All patients in this multicentre study were followed for at least 10 years and main outcomes were clinical efficacy, duration of relief, BEI-U and BEI-%, and frequency of adverse events.

Results

BEB, HFS, and EN patients received a mean BoNT-A dose with a significant inter-group difference (P<0.0005, respectively). The mean (±SD) effect duration was statistically different (P=0.009) among three patient groups. Regarding the BoNT-A escalation indexes, the mean (±SD) values of BEI-U and BEI-% were statistically different (P=0.035 and 0.047, respectively) among the three groups. In BEB patients, the BEI-% was significantly increased in younger compared with older patients (P=0.008). The most frequent adverse events were upper lid ptosis, diplopia, ecchymosis, and localized bruising.

Conclusions

This long-term multicentre study supports a high efficacy and good safety profile of BoNT-A for treatment of BEB, HFS, and EN. The BEI indexes indicate a significantly greater BoNT-A-dose escalation for BEB patients compared with HFS or EN patients and a significantly greater BEI-% in younger vsolder BEB patients. These results confirm a greater efficacy in the elderly and provide a framework for long-term studies with a more flexible and reliable evaluation of drug-dose escalation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benign essential blepharospasm (BEB) is a focal cranial dystonia characterized by excessive involuntary contractions of the eyelid muscles. It is usually bilateral, although it may be unilateral briefly at onset.1, 2, 3 Initial symptoms include unpleasant sensations, eyelid fluttering, and increased blink rate in response to stimuli, progressing eventually to chronic involuntary spasms in both eyes.4 Quality of life may be significantly impaired, with increased difficulty in reading, writing, and driving.5 BEB is estimated to affect between 16 and 133 out of 1 000 000 individuals in the general population6, 7 and is increasingly being recognized as cause of visual disability responsible for about 32 out of 100 000 people.8, 9 An estimated 20 000–50 000 people are affected in the USA, with approximately 2000 new cases of BEB diagnosed annually.7 Typically beginning in the fifth or sixth decade of life, it affects women more frequently than men (3 : 1)10 and the elderly.6

Botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT-A) therapy for strabismus was introduced by Scott11 in the early 1980s, and in 1989 the Food and Drug Administration approved BoNT-A for ophthalmologic and neurologic use in treating strabismus, blepharospasm, and hemifacial spasm (HFS).12 Since then, BoNT-A has replaced eyelid surgery as the first-line therapy for BEB,13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and has become the treatment of choice, as it is very successful in controlling eyelid spasms.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Although some authors have reported decreasing effectiveness with prolonged use,23, 30 others have not observed this in the majority of patients.24, 31 There is no evidence that prolonged treatment has any adverse effects related either to the chemodenervation of adjacent non-target muscle groups by the toxin or to the injection technique. Complications include localized bruising, ecchymosis, ptosis, exposure keratopathy, diplopia, mid-facial weakness, lagophthalmos, and dry eye.

HFS, a form of segmental myoclonus, is typically characterized by involuntary unilateral tonic and clonic contractions of the face. Onset is usually in the fifth and sixth decades and occurs more commonly in women (2 : 1) with an overall prevalence of about 10 : 100 000. However, in some populations, such as Asians, the prevalence is much higher.32 Some patients may be genetically predisposed to developing HFS,33 but most cases are sporadic.9 Unlike blepharospasm, HFSs persist during sleep and are not related to hypersensory input. The anatomical basis for the spasms is believed to be mechanical irritation of the facial nerve at its exit root by compression from one or more adjacent arteries or veins. The condition may be bilateral in rare instances, and can cause significant cosmetic and functional disability. Although neurosurgical treatment is available, the potential complications and relatively high recurrence rate have made botulinum toxin A the preferred symptomatic treatment for HFS.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 As HFS rarely remits spontaneously,40 most patients need to continue BoNT-A treatment for many years, if not for the rest of their lives. The long-term efficacy and safety of BoNT-A are, therefore, increasingly important questions. Few of the numerous published studies assessing BoNT-A treatment for HFS34, 36, 37, 40, 41 included patients with serial treatment spanning several years and none had follow-up past 5 years.

Spastic entropion (EN) is a form of EN in which the lower eyelid margin is turned in, with a riding up of the pre-tarsal orbicularis muscle, and often accompanies involutional EN. In older patients with pre-existing lid laxity, ocular irritation after ocular surgery can sometimes cause a reflexive orbicularis muscle spasm, resulting in muscle override and EN that often resolves after a few weeks or months. Temporary relief can be achieved by weakening lower eyelid muscle tone with 5–10 U botulinum toxin injected into the pre-tarsal or pre-septal orbicularis muscle.42, 43, 44, 45 This can completely eliminate the EN for up to 3–4 months. Botulinum toxin is a highly effective temporary EN treatment with few complications and no adverse effects on the results of surgical EN repair.39

Treatment of blepharospasm and HFS with BoNT-A has been found to alleviate symptoms and enhance quality of life.5, 46 Whereas most patients show long-term clinical improvement with repeated injections, however, some eventually stop responding and others fail to respond at all.13, 24, 30 Although BoNT-A has been used for many years to treat focal dystonia-like blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, and HFS, there are little data on its long-term efficacy.47 Furthermore, earlier studies have explored the limitations of BoNT-A; in particular, the development of secondary resistance to therapy.48 Two recent reports suggest that higher doses and long-term use with shorter duration between treatments increase the risk of antibody formation and treatment failure.49, 50 Recently, two studies also confirmed that higher doses of BoNT-A than recommended (50 U × eye) may be needed for some patients.51, 52 Therefore, it is important to determine whether efficacy with high-dose therapy can be sustained for long treatment periods without developing resistance, and whether the risk of complications is increased.

The aim of this multicentre study was to investigate the long-term effectiveness and safety of BoNT-A treatment in patients with BEB, primary HFS, and EN. We followed up regularly with patients for at least 10 years to compare the duration of relief, the number of doses needed, clinical efficacy, frequency of adverse reactions, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and antidepressant use among the three patient groups. In particular, we examined the variations in therapeutic dosage using new, modified indexes already used in other drug therapies and considered effective in the evaluation of drug-dose escalation.53 Finally, we assessed the effectiveness of BoNT-A treatment in relationship to patient variables, such as age and gender.

Materials and methods

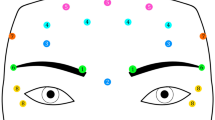

This multicentre study was conducted at the Ophthalmology Section, Department of Clinical Neuroscience of Palermo University, Italy and at the Service d’Ophtalmologie, Hôpital Foch, Suresnes, Paris, France. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this prospective study. All patients received a diagnosis of BEB, primary HFS, or EN according to published criteria and began treatment with BoNT-A (Botox, Allergan, Irvine, California, USA) injections between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 1998. Patients who were followed up for at least 10 years were enrolled in this prospective study. Both centres used standard methods for recording information, injecting BoNT-A, and assessing treatment effectiveness.54 The injections were performed by two experienced surgeons (NG and SD) one for each centre; site of injection and the BoNT-A dosage were determined according to Helveston.55 Patients with other neurological defects, including ocular motility or eyelid problems or facial spasm grade <2, were excluded from the study.

A total of 173 patients completed the 10-year follow-up: 83 patients with BEB, 65 with HFS, and 25 with EN. Of these, 18 did not attend follow-up visits for 12 months or more and were thus considered as ‘dropouts.’ Of the 18 dropouts, 6 had not discontinued BoNT-A therapy, but had switched to other treatment centres closer to their homes. Reasons for treatment discontinuation included death from other causes (five patients) and unsatisfactory results (four patients). Three patients dropped out for unknown reasons.

To assess the long-term effectiveness and safety of BoNT-A, we reviewed patients’ medical records for the 10 years of follow-up and collected the following demographic and clinical patient data for each group: age and gender, concomitant systemic diseases, duration of disease, earlier facial paralysis, date of BoNT-A injections, total dose for each injection, number and location of injection sites, duration of effect (defined as the interval between treatment and the recurrence of symptoms severe enough to prompt patients to receive another injection), quality of the effect induced by the preceding treatment, and occurrence and duration of adverse effects. Before each injection session, patients were questioned about the results of the earlier session. The severity of diagnosis and the subjective efficacy of the BoNT-A treatment were measured using a patient self-evaluation scale. At each injection visit, changes in the patient's status were scored as no change (muscle spasms that interfered with activities of daily living or social tasks in such a way that patients continued to be socially embarrassed), moderate improvement (reduction in the frequency and duration of spasms, so that they interfered only slightly with activities of daily living or social tasks), or marked improvement (spasms in the injected muscle had ceased altogether, so that they no longer interfered with activities of daily living or social tasks). Furthermore, the self-administered questionnaire included three questions about the frequency of anxiety or depressive symptoms and use of antidepressants in the three groups of patients.

For age analysis, patients were categorized into two groups: under 65 years old and ⩾65 years old. To assess the inter- and intra-group variations among BEB, HFS, and EN patients for scheduling dosage regimens of BoNT-A, we used two new, modified indexes already used in other fields of drug therapy and considered effective in evaluation of drug-dose escalation.53 For the calculation of these indexes (evaluated in U and in per cent of BoNT-A-dose escalation), the botulinum toxin starting dose (BSD), the botulinum toxin maximum dose (BMD), and the total days of duration effect between treatments were recorded for each patient. The botulinum toxin escalation index in U (BEI-U) was calculated as the mean increase in botulinum toxin dosage (in U) using the following formula: (BMD–BSD)/days. The botulinum toxin escalation index percentage (BEI-%) was calculated as the mean percentage of increase in botulinum toxin dosage from BSD using the following formula: [(BMD–BSD)/BSD]/(days × 100).52 Any local and systemic side effects attributable to BoNT-A therapy were evaluated at each injection time.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Epi Info software, version 3.2.2 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) and SPSS Software (version 14.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results are expressed as mean±standard deviation. To compare parametric variables among patient groups, univariate analysis of variance test was used and post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni test was used to determine whether there were multiple differences. When a normal distribution was not expected, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Changes between baseline and follow-up values were compared using the paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test, as needed. A two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Of the 155 patients treated with BoNT-A who completed the 10-year course of follow-up, 73 (22M/51F) patients had BEB, 58 (21M/37F) had HFS, and 24 (12M/12F) had EN (Table 1). There were more females (P<0.05) compared with males in both the BEB and HFS groups, but not in the EN group. There was a significant difference in mean age among the three groups, with patients in the EN group older (P=0.024) compared with the BEB and HFS patient groups (Table 1). Furthermore, duration of the disease was significantly shorter in the EN patient group (P=0.001). No difference was found among patient groups for concomitant systemic disease, though earlier facial paralysis was more frequently found in the HFS patient group (P=0.004) (Table 1).

BEB, HFS, and EN patient groups received a total of 529, 391, and 64 treatments and a mean treatment number of 8.7 (±7.1), 7.8 (±5.5), and 2.7 (±3.2), respectively, with a significant difference among diagnosis groups (P=0.006). Post hoc analysis (Bonferroni test) showed significant differences between the EN group and both BEB and HFS groups (P=0.005 and 0.020, respectively) (Table 2). The frequency of patients who needed only one dose of BoNT-A were 14/73 (19.2%) for BEB, 9/58 (15.5%) for HFS, and 13/24 (54.2%) for EN, with a statistical significant difference in favour of the EN patient group (P<0.0005). On average, each patient received a mean BoNT-A dose of 28.2 (±12.2) U for BEB, 18.7 (±9.4) U for HFS, and 10.6 (±4.7) U for EN patients, with a statistically significance difference among the groups (P<0.0005). Post hoc analysis (Bonferroni test) showed significant differences between the BEB group and both HFS and EN groups (P<0.0005 in both cases) and between the HFS group and EN group (P=0.005) (Table 2). The mean (±SD) effect duration was 18.2 (±12.3) weeks for BEB, 20.6 (±11.6) weeks for HFS, and 13.7 (±7.0) weeks for EN, with statistically significant inter-group difference (P=0.009) (Table 2).

For analysis of the BoNT-A escalation index, the mean (±SD) values of BEI-U were 0.027 (±0.05), 0.008 (±0.01), and 0.005 (±0.01) for the BEB, HFS, and EN, respectively, groups with a statistically significant difference among the groups (P=0.035). Post hoc analysis (Bonferroni test) showed significant differences between the BEB group and both HFS and EN groups (P=0.028 and 0.022, respectively). The mean (±SD) values of BEI-% were 0.169 (±0.24), 0.053 (±0.08), and 0.068 (±0.10) for BEB, HFS, and EN groups, respectively, with a statistical significant difference among groups (P=0.047) (Table 2).

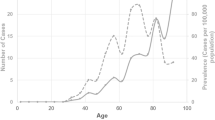

Significant intra-group differences were found for mean dosages, which increased significantly (P<0.05) after the first three or four doses of treatment for both BEB and HFS patient groups. No significant difference was found in the duration effect between BEB and HFS patient groups (Figures 1 and 2).

In 23/73 (31.5%), 18/58 (31.0%), and 1/24 (4.2%) patients with BEB, HFS, and EN, respectively, local adverse events occurred (Table 3). The most frequently reported adverse reaction was upper lid ptosis, followed by diplopia, ecchymosis, and localized bruising on the side of injection. Although there was a significant difference (P=0.023) in total side effects among three patient groups because of the low incidence of complications in the EN group, the incidence of side effects was similar in the BEB and HFS groups. Of the 42 patients with adverse effects, 32 had only one adverse event and two patients had more than two complications. Local adverse events were rated as mild to moderate and resolved without sequelae, but they interfered with daily activities and social tasks in approximately 30% of cases. The mean dose of BoNT-A was not significantly higher for injection sessions that induced adverse reactions than for sessions that did not (P=0.480).

Symptoms of anxiety were more frequently found in the HFS patient group (P=0.045), but there were no significant differences in depressive mood or use of antidepressants among patient groups.

According to patients’ subjective impressions, nearly all treatments improved BEB and HFS, with response rates of 96 and 98%, respectively. BoNT-A was also highly effective in temporary treatment of spastic EN. No systemic side effects of BoNT-A treatment were noted, a finding consistent with the medical reports (no cases of anaphylaxis or death). There were no significant gender-based differences between the three patient groups. In patients with blepharospasm, the BEI-% was significantly increased in younger compared with older patients (P=0.008), whereas no age group differences were found in HFS patients. The intra-group analysis performed by age group and diagnosis showed that the mean dosages of BoNT-A were significantly increased during follow-up in older BEB and HFS patients (P<0.05). Furthermore, the duration effect increased significantly in these patients as treatment progressed (P<0.05). No differences in duration effect and dosage were found in younger BEB and HFS patients. No difference in the incidence of adverse effects was found according in the age group analysis for BEB (P=0.848) and HFS (P=0.166) patients.

Discussion

Our multicentre study provided a larger sample of patients with BEB, HFS, and spastic EN receiving BoNT-A treatment than would be possible with one centre alone. It also had the advantage of a 10-year follow-up. The study data support the high efficacy and good safety profile of BoNT-A for treatment of BEB, HFS, and EN without increased risk of side effects. A total of 96% of patients with BEB, 98% of patients with HFS, and 100% of patients with EN had significant relief of their symptoms.

Although BoNT-A has been used to treat BEB, HFS, and EN for several years, most available studies describe relatively short treatment courses and follow-up, with few patients receiving continuous treatment throughout the study.16, 25, 29, 36, 45, 56 Little work has been done to track longer-term outcomes in terms of response rates, duration of improvement, and long-term adverse reactions.28, 40, 47, 57, 58 In our long-term, multicentre study, we have obtained at least a 96% response rate and a mean duration of improvement of 18, 21, and 14 weeks for BEB, HFS, and EN, respectively. This outcome compares well with shorter-term study results. The effectiveness of BoNT-A treatment in relieving the symptoms of BEB, HFS, and EN, as measured by the response rate and average duration of improvement, remained unchanged over the treatment years. Hence, BoNT-A use produces substantial, sustained relief over time for BEB and HFS. Our study also confirms results of other studies showing that botulinum toxin is a highly effective temporary treatment for EN, with few complications and no adverse effects on the results of surgical EN repair.39, 45, 59

The clinical reestablishment of muscle function after BoNT-A injections requires repeated injections over long periods.49, 50 The onset of resistance to botulinum toxin over time may be due to the immunological properties of the toxin that lead to the stimulation of antibody production, thus rendering further treatments ineffective.48, 49, 50, 51 Greene and Fahn49 found that patients resistant to botulinum toxin received more booster injections early after treatment, as well as higher doses compared with responsive patients. These authors, therefore, recommended that the lowest possible effective dose should be used, with treatment intervals of at least 3 months, and that booster injections be avoided. Atassi and Oshima50 confirmed these findings by showing an association of high-dose, high-frequency botulinum toxin injections with increased antigenicity.

In our study, we have for the first time used two indexes that are already widely used in other drug therapy studies53, 60 for assessing the medium, long-term effects of a specific treatment with uncertain duration. These indexes, namely ‘botulin toxin escalation index-U’ (BEI-U) and ‘botulin toxin escalation index percentage’ (BEI-%), include several factors, but are easy to calculate for different settings and periods and can be used to compare data in clinical trials. This dynamic tool can be useful to describe a trend in botulinum toxin treatment response, in which multiple factors can be identified in the clinical records, and can be used for the entire treatment period or for restricted periods of time.

In our prospective study, we found an increase in mean dosages for BEB and HFS patients with no statistically significant change in duration of relief during the follow-up period. Furthermore, subgroup analysis according to age (< or ⩾65 years) indicates a significant increase in duration of relief and mean doses over the follow-up period in older but not younger BEB and HFS patients. Using BEI-U and BEI-%, we found a significantly greater BoNT-A-dose escalation for BEB patients compared with HFS or EN patients. In particular, a significantly greater BEI-% was found in younger vs older BEB patients.

These results suggest early underdosing, but only in older BEB and HFS patients. Furthermore, as reported for BoNT-A (Dysport) treatment by Truong et al,61 the BEI-U and BEI-% data confirm a greater efficacy in the elderly, who may have lower muscle bulk than younger people and who may require a lower-dose escalation to achieve optimal benefit.

Our data provide a framework for long-term studies in which a more flexible and reliable evaluation of dose escalation as a function of variable treatment time for different diseases is required.

Consistent with earlier studies,9, 39, 62 30% of our patients showed one or more side effects, including eyelid ptosis, ecchymosis, diplopia, and localized bruising occurred. Adverse events were rated as mild to moderate and resolved without sequelae. There was no evidence that prolonged treatment or age increased adverse effects. We found that anxiety was more frequent in the HFS patient group (P=0.045), emphasizing the need for treatments such as BoNT-A injections, which have showed to improve the quality of life and reduce the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with blepharospasm.46

Some potential limitations of our study include the retrospective nature of our analysis and the use of a patient self-evaluation scale, which have earlier been used effectively,58 rather than an observer-based rating to determine the effect of BoNT-A treatment on BEB, HFS, and EN patients. However, the large effect reported in other studies (over 90% of patients benefit) makes it difficult and probably unethical to perform controlled trials for the efficacy of BoNT-A. Future trials should explore technical factors, such as the optimal treatment intervals and the effects of different injection techniques, doses, botulinum toxin types, and formulations. Other issues include service delivery, quality of life, long-term efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity. Although botulinum neurotoxin injections are currently the mainstay of therapy, other therapies are on the horizon.17, 38, 46, 63, 64

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Jankovic J, Orman J . Blepharospasm: demographic and clinical survey of 250 patients. Ann Ophthalmol 1984; 16: 371–376.

Grandas F, Elston J, Quinn N, Marsden CD . Blepharospasm: a review of 264 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988; 51: 767–772.

Vitek JL . Pathophysiology of dystonia: a neuronal model. Mov Disord 2002; 17: S49–S62.

Jankovic J, Havins WE, Wilkins RB . Blinking and blepharospasm. Mechanism, diagnosis, and management. JAMA 1982; 248: 3160–3164.

Reimer J, Gilg K, Karow A, Esser J, Franke GH . Health-related quality of life in blepharospasm or hemifacial spasm. Acta Neurol Scand 2005; 111: 64–70.

Epidemiological Study of Dystonia in Europe (ESDE) Collaborative Group. A prevalence study of primary dystonia in eight European countries. J Neurol 2000; 247: 787–792.

Defazio G, Livrea P . Epidemiology of primary blepharospasm. Mov Disord 2002; 17: 7–12.

Cossu G, Mereu A, Deriu M, Melis M, Molari A, Melis G et al. Prevalence of primary blepharospasm in Sardinia, Italy: a service-based survey. Mov Disord 2006; 21: 2005–2008.

Kenney C, Jankovic J . Botulinum toxin in the treatment of blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. J Neural Transm 2008; 115: 585–591.

Anderson RL, Patel BC, Holds JB, Jordan DR . Blepharospasm: past, present and future. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 14: 305–317.

Scott AB . Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology 1980; 87: 1044–1049.

FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Botulinum toxin type A (Botox), Allergan, Inc. Product approval information, licensing action, 2000a. Available at:http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/appletter/2000/botaller122100L.htm.

Porter JD, Strebeck S, Capra NF . Botulinum-induced changes in monkey eyelid muscle. Comparison with change seen in extraocular muscle. Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109: 396–404.

Siatkowski RM, Tyutyunikov A, Biglan AW, Scalise D, Genovese C, Raikow RB et al. Serum antibody production to botulinum A toxin. Ophthalmology 1993; 100: 1861–1866.

Huang W, Foster JA, Rogachefsky AS . Pharmacology of botulinum toxin. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43: 249–259.

Snir M, Weinberger D, Bourla D, Kristal-Shalit O, Dotan G, Axer-Siegel R . Quantitative changes in botulinum toxin a treatment over time in patients with essential blepharospasm and idiopathic hemifacial spasm. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136: 99–105.

Costa J, Espírito-Santo C, Borges A, Ferreira JJ, Coelho M, Moore P et al. Botulinum toxin type A therapy for blepharospasm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (1): CD004900.

Mauriello JA . Blepharospasm, Meige syndrome, and hemifacial spasm: treatment with botulinum toxin. Neurology 1985; 35: 1499–1500.

Scott AB, Kennedy RA, Stubbs HA . Botulinum A toxin injection as a treatment for blepharospasm. Arch Ophthalmol 1985; 103: 347–350.

Cohen DA, Savino PJ, Stern MB, Hurtig HI . Botulinum injection therapy for blepharospasm: a review and report of 75 patients. Clin Neuropharmacol 1986; 9: 415–429.

Dutton JJ, Buckley EG . Botulinum toxin in the management of blepharospasm. Arch Neurol 1986; 43: 380–382.

Elston JS . Long-term results of treatment of idiopathic blepharospasm with botulinum toxin injections. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 664–668.

Engstrom PF, Arnoult JB, Mazow ML, Prager TC, Wilkins RB, Byrd WA et al. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin therapy for essential blepharospasm. Ophthalmology 1987; 17: 971–975.

Dutton JJ, Buckley EG . Long-term results and complications of botulinum A toxin in the treatment of blepharospasm. Ophthalmology 1988; 95: 1529–1534.

Taylor JD, Kraft SP, Kazdan MS, Flanders M, Cadera W, Orton RB . Treatment of blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm with botulinum A toxin: a Canadian multicentre study. Can J Ophthalmol 1991; 26: 133–138.

Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Training guidelines for the use of botulinum toxin for the treatment of neurologic disorders. Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment. Neurology 1994; 44: 2401–2403.

Dutton JJ . Botulinum-A toxin in the treatment of craniocervical muscle spasms: short- and long-term, local and systemic effects. Surv Ophthalmol 1996; 41: 51–65.

Calace P, Cortese G, Piscopo R, Della Volpe G, Gagliardi V, Magli A et al. Treatment of blepharospasm with botulinum neurotoxin type A: longterm results. Eur J Ophthalmol 2003; 13: 331–336.

Roggenkämper P, Jost WH, Bihari K, Comes G, Grafe S . for the NT 201 Blepharospasm Study Team. Efficacy and safety of a new Botulinum Toxin Type A free of complexing proteins in the treatment of blepharospasm. J Neural Transm 2006; 113: 303–312.

Frueh BR, Musch DC . Treatment of facial spasm with botulinum toxin. An interim report. Ophthalmology 1986; 93: 917–923.

Gonnering RS . Treatment of hemifacial spasm with botulinum A toxin. Results and rationale. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1986; 2: 143–146.

Auger RG, Whisnant JP . Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Arch Neurol 1990; 47: 1233–1234.

Micheli F, Scorticati MC, Gatto E, Cersosimo G, Adi J . Familial hemifacial spasm. Mov Disord 1994; 9: 330–332.

Wang A, Jankovic J . Hemifacial spasm: clinical findings and treatment. Muscle Nerve 1998; 21: 1740–1747.

Yoshimura DM, Aminoff MJ, Tami TA, Scott AB . Treatment of hemifacial spasm with botulinum toxin. Muscle Nerve 1992; 15: 1045–1049.

Elston JS . The management of blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. J Neurol 1992; 239: 5–8.

Flanders M, Chin D, Boghen D . Botulinum toxin: preferred treatment for hemifacial spasm. Eur Neurol 1993; 33: 316–319.

Costa J, Espírito-Santo C, Borges A, Ferreira JJ, Coelho M, Moore P et al. Botulinum toxin type A therapy for hemifacial spasm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (1): CD004899.

Dutton JJ, Fowler AM . Botulinum toxin in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 2007; 52: 13–31.

Mauriello JA, Leone T, Dhillon S, Pakeman B, Mostafavi R, Yepez MC . Treatment choices of 119 patients with hemifacial spasm over 11 years. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1996; 98: 213–216.

Jitpimolmard S, Tiamkao S, Laopaiboon M . Long term results of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of hemifacial spasm: a report of 175 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64: 751–757.

Carruthers J, Stubbs HA . Botulinum toxin for benign essential blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm and age-related lower eyelid entropion. Can J Neurol Sci 1987; 14: 42–45.

Neetens A, Rubbens MC, Smet H . Botulinum A-toxin treatment of spasmodic entropion of the lower eyelid. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 1987; 224: 105–109.

Clarke JR, Spalton DJ . Treatment of senile entropion with botulinum toxin. Br J Ophthalmol 1988; 72: 361–362.

Steel DH, Hoh HB, Harrad RA, Collins CR . Botulinum toxin for the temporary treatment of involutional lower lid entropion: a clinical and morphological study. Eye 1997; 11: 472–475.

Ochudlo S, Bryniarski P, Opala G . Botulinum toxin improves the quality of life and reduces the intensification of depressive symptoms in patients with blepharospasm. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007; 13: 505–508.

Vogt T, Lüssi F, Paul A, Urban P . Long-term therapy of focal dystonia and facial hemispasm with botulinum toxin A. Nervenarzt 2008; 79: 912–917.

Dressler D, Münchau A, Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Bigalke H . Antibody-induced botulinum toxin therapy failure: can it be overcome by increased botulinum toxin doses? Eur Neurol 2002; 47: 118–121.

Greene P, Fahn S . Development of resistance to Botulinum toxin type A in patients with torticollis. Mov Disord 1994; 9: 213–217.

Atassi MZ, Oshima M . Structure, activity and immune recognition of botulinum neurotoxins. Crit Rev Immunol 1999; 19: 219–260.

Pang AL, O’Day J . Use of high-dose botulinum A toxin in benign essential blepharospasm: is too high too much? Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2006; 34: 441–444.

Levy RL, Berman D, Parikh M, Miller NR . Supramaximal doses of botulinum toxin for refractory blepharospasm. Ophthalmology 2006; 113: 1665–1668.

Mercadante S, Dardanoni G, Salvaggio L, Armata MG, Agnello A . Monitoring of opioid therapy in advanced cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 13: 204–212.

Berardelli A, Abbruzzese G, Bertolasi L, Cantarella G, Carella F, Currà A et al. Guidelines for the therapeutic use of botulinum toxin in movement disorders. Italian Study Group for Movement Disorders, Italian Society of Neurology. Ital J Neurol Sci 1997; 18: 261–269.

Helveston EM . Surgical Management of Strabismus. An Atlas of Strabismus Surgery, 4th ed. St Louis: CV Mosby, 1993, pp 345–354.

Drummond GT, Hinz BJ . Botulinum toxin for blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm: stability of duration of effect and dosage over time. Can J Ophthalmol 2001; 36: 398–403.

Ainsworth JR, Kraft SP . Long-term changes in duration of relief with botulinum toxin treatment of essential blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. Ophthalmology 1995; 102: 2036–2040.

Defazio G, Abbruzzese G, Girlanda P, Vacca L, Currà A, De Salvia R et al. Botulinum toxin A treatment for primary hemifacial spasm: a 10-year multicenter study. Arch Neurol 2002; 59: 418–420.

Wabbels B, Förl M . Botulinum toxin treatment for crocodile tears, spastic entropion and for dysthyroid upper eyelid retraction. Ophthalmologe 2007; 104: 771–776.

Lowe SS, Nekolaichuk CL, Fainsinger RL, Lawlor PG . Should the rate of opioid dose escalation be included as a feature in a cancer pain classification system? J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 35: 51–57.

Truong D, Comella C, Fernandez HH, Ondo WG . Dysport Benign Essential Blepharospasm Study Group. Efficacy and safety of purified botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) for the treatment of benign essential blepharospasm: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2008; 14: 407–414.

Simpson DM, Blitzer A, Brashear A, Comella C, Dubinsky R, Hallett M et al. Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: Botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of movement disorders (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2008; 70: 1699–1706.

Hallett M, Evinger C, Jankovic J, Stacy M . BEBRF International Workshop. Update on blepharospasm: report from the BEBRF International Workshop. Neurology 2008; 71: 1275–1282.

Cetinkaya A, Brannan PA . What is new in the era of focal dystonia treatment? Botulinum injections and more. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2007; 18: 424–429.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cillino, S., Raimondi, G., Guépratte, N. et al. Long-term efficacy of botulinum toxin A for treatment of blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, and spastic entropion: a multicentre study using two drug-dose escalation indexes. Eye 24, 600–607 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.192

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.192

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

How to face the hemifacial spasm: challenges and misconceptions

Acta Neurologica Belgica (2024)

-

Validation of a new hemifacial spasm grading questionnaire (HFS score) assessing clinical and quality of life parameters

Journal of Neural Transmission (2021)

-

Botulinum Toxin for the Head and Neck: a Review of Common Uses and Recent Trends

Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports (2020)

-

Treatment of blepharospasm and Meige’s syndrome with abo- and onabotulinumtoxinA: long-term safety and efficacy in daily clinical practice

Journal of Neurology (2020)