Abstract

Purpose

To describe the incidence and current management of fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom.

Methods

Cases were identified prospectively through the British Ophthalmologic Surveillance Unit (BOSU) from December 2003 to November 2005. Questionnaire data were requested at diagnosis and at 6 months follow-up. Inclusion criteria were a positive culture or microsopic proof from a scraping or biopsy, and a normal residence in the United Kingdom.

Results

Data were available on 39 confirmed cases at diagnosis and 34 cases at follow-up. The minimum average annualised incidence was 0.32 (95% CI, 0.24–0.44) cases per million individuals. In 22 cases (56%), only Candida was isolated and 14 of these (63%) had prior ocular surface disease treated with topical steroid. A filamentary fungus infection was more common in male patients (P=0.02), often following trauma, and the differences in risk factors between types of fungal infection was statistically significant (P<0.001). One case had a mixed yeast and filamentary fungus infection. The most frequent initial topical therapies were amphotericin B (38%) or econazole (28%). In addition, oral fluconazole was used in 11 (31%) patients and oral itraconazole in six (15%). At follow-up, the vision in 15 eyes (44%) was <6/60 including three eyes eviscerated.

Conclusions

This study provides data on the minimum incidence of fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom. It provides evidence of frequent delay in diagnosis after presentation to eye departments, inconsistent management, and poor outcome. Issues that can now be addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fungal keratitis is a potentially devastating ocular infection. The true incidence is unknown, but the figure is likely to vary according to regional differences in climate, urbanisation, and occupation. In tropical and rural areas, fungi can be the predominant isolate from cases of suppurative keratitis, where it is typically the result of filamentary fungal infection following trauma.1 The proportion of cases with fungal keratitis who have yeast infection is greater in temperate countries where chronic ocular surface disease is the major risk factor.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

To provide data on the incidence, risk factors for infection, current management, and the outcome of fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom, we have performed the first national prospective survey that was carried over a period of 2 years. This included all cases reported to the British Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (BOSU).14

Materials and methods

This was a 2-year population-based prospective survey of cases through the BOSU monthly reporting card system. At the end of each month, all consultants and associate specialists throughout the United Kingdom (approximately 1100 doctors) were asked to indicate a new case or confirm that no cases had been seen. Case notification was requested for a 24-month study period from December 2003 to November 2005 inclusive. Cases were defined as any patient with an episode of suppurative keratitis from which at least one positive fungal isolate that was not considered to be a contaminant was obtained after culture of samples of corneal tissue, or a case of suppurative keratitis from which fungal elements were identified by microscopy of appropriately stained tissue. There were no age restrictions, and patients normally residing outside the United Kingdom were excluded. To maximise recruitment, the aims of the study were publicised in special interest groups for corneal disease in the United Kingdom. The protocol was reviewed by the BOSU steering committee and the approval was obtained form the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee.

Following the notification of a positive case to BOSU, the reporting ophthalmologist was sent an incident questionnaire by the study investigators. Information requested included suspected risk factors for infection, the nature of the isolate, if a positive culture had been obtained, and the initial management. Specific information on a prior history of ocular trauma, microbial keratitis, contact lens wear, recent surgery, dry eye, persistent epithelial defect, and topical steroid use were requested, with space for additional comments as free text if other local or systemic risk factor were present. For this study, a history of a prior corneal graft was considered as ocular surface disease. Outcome data from cases that matched the inclusion criteria were obtained from a follow-up questionnaire sent to the reporting ophthalmologist 6 months after diagnosis. If a questionnaire was not returned at least two reminder letters were sent. The incidence was calculated using the estimated population (59.9 million) of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) at the midpoint of the study period.15 Ethical approval to record the postcode of the normal residence of cases was not sought and an analysis of distribution of cases was not attempted.

A single case with mixed fungal infection was excluded from the subsequent risk analysis. Differences in the distribution of categorical variables between yeast and filamentous groups were compared using Fisher's exact test. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare ages and grouped visual outcomes. A P-value of ⩽0.05 was considered as evidence of significance. Subgroup analysis of visual outcome according to species of fungus was not performed because of the low number of cases.

Results

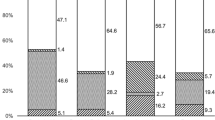

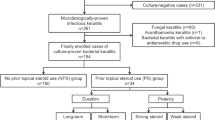

In the 24-month study period, 88 incident forms were received, of which 49 forms were excluded. Fourteen of these 49 forms were errors (ie, ‘false’ reports on patients that did not have fungal infection, or only presumed infection), 13 were duplicate reports, and 14 reported cases with fungal keratitis did not fulfil the study inclusion criteria (ie, they developed disease outside the study period or they were cases referred from outside the United Kingdom). A notification form only was received in eight cases, but the initial questionnaire was not returned, and these were considered as ‘potential cases’. Therefore, a total of 39 eligible questionnaires were received at baseline from 31 ophthalmologists in 23 centres, with 21 cases in the first year and 18 in the second year. Follow-up forms at 6 months were received for 34 of the 39 cases. In total, 22 (56%) cases had yeast infection, 16 (41%) had filamentary fungal infection, and one case (an 88-year-old female patient) had a mixed infection of penicillium and yeast while applying topical steroid following penetrating keratoplasty (Table 1). The minimum average total annualised incidence was 0.32 per million individuals (95% CI, 0.24–0.44), with 0.19 per million (95% CI, 0.13–0.29) having a yeast corneal infection and 0.14 per million (95% CI, 0.09–0.23) having a filamentary fungus corneal infection. During the study period, the average monthly response rate to the BOSU reporting system was 78%. Therefore, assuming that all eight incident forms for which a questionnaire was not returned (potential cases) were eligible for inclusion, and accounting for underreporting, the maximum annualised incidence for the study period was 0.50 cases per million individuals (95% CI, 0.39–0.64).

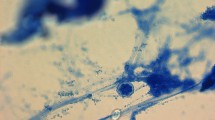

The average interval between presentation to an eye care service and confirmation of the diagnosis of fungal keratitis was 31 days (median 14 days, range: 0–145). There was no difference in distribution of delay in diagnosis between the yeast and filamentary fungal keratitis groups (P=0.381). Positive cultures were obtained in 35 (90%) of the cases (36 isolates); in two cases, a yeast was only identified in a smear and in two cases, a filamentous fungus was only identified in a tissue biopsy. Of the 39 cases, 24 (61%) were female and the right eye was involved in 16 (41%) patients. There was an association between gender and type of infection; with yeast infection more common in female patients, whereas filamentary fungal infection was more common in male patients (P=0.02). Confirmation of fungal infection was not more common in the warmer half of the year (1 April–30 September) for either yeast or filamentary fungi (P=0.33; Table 2).

A history of prior ocular surface disease was present in 25 (64%) eyes before the development of fungal keratitis. In the order of frequency, the ocular surface disease types were severe dry eye (eight cases), bullous keratopathy (seven cases), allergic eye disease (five cases), prior microbial infection (two cases), rosacea keratitis, recurrent erosion syndrome, and penetrating keratoplasty (one case each). Ocular surface disease was present in 100% of 22 eyes with pure yeast infection, and 2 of 16 (12%) eyes with pure filamentary fungal infection. Before the confirmation of diagnosis, 14 (63%) of the 22 cases with pure yeast infection and 6 (38%) of the 16 cases with pure filamentary fungal infection had been treated with topical steroid, but this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.188). Eleven (69%) cases of filamentary fungal infection developed after trauma, and three cases developed infection secondary to cosmetic contact lens wear (one isolate each of Scedosporium apiospermum, Fusarium solani, and Fusarium dimerum), but the details of the contact lens type or the care system used were not recorded. Three cases of yeast infection with chronic ocular surface disease were receiving treatment with systemic immunosuppression at the onset of infection; one patient with yeast infection was known to be HIV positive. The data showed that there was a strong association between the species of fungus identified and risk for infection. Yeast infection was only found in cases with prior ocular surface disease, whereas filamentary fungal infection occurred with prior ocular surface disease, trauma, and cosmetic contact lens wear (P<0.001).

Microbial coinfection was identified in 10 cases—eight with yeast and two with a filamentary fungus. In one patient with an agricultural injury, Acanthamoeba was cultured and a filamentous fungus was later identified in the keratoplasty specimen. The second patient with Acanthamoeba keratitis secondary to contact lens wear and a persistent epithelial defect developed a secondary yeast infection. Although microbial coinfection was more common in eyes with yeast infection than filamentary infection, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.143). The presence of a hypopyon was more common in filamentary fungal infections than in yeast infections (P=0.029), but other clinical signs were not compared. Two eyes with filamentary fungal infection (Aspergillus fumigatus, Cylindrocarpon sp.) progressed to endophthalmitis.

The preferred initial topical agents were amphotericin B (38%), econazole (28%), miconazole (15%), and clotrimazole (8%; Table 3). Sixteen eyes were treated with topical agents alone. The average duration of topical treatment was 14 weeks (median 12, range: 2–62 weeks). The preferred oral agents for initial treatment were fluconazole (31%), itraconazole (15%), ketaconazole (5%), and voriconazole (5%). The average duration of oral treatment was 8 weeks (median 5 weeks, range: 1–44 weeks). After investigation or at the time of resolution of infection, six (18%) cases had changed their topical treatment and 11 (32%) had been started on or had a change in their oral treatment, with the addition of oral voriconazole in six cases. Although cases with filamentary fungal infection tended to get topical treatment for longer than cases with yeast infection (the median duration of use of topical treatment in filamentary infections was 5.5 weeks compared with 5 weeks in yeast infections), this difference was not statistically significant at the 5% level (P=0.0563). There was also no significant difference in the distribution of duration of oral treatment between the two groups (P=0.619).

At the 6-month observation period, after the onset of infection, corneal graft surgery had been performed in 10 of the 34 eyes with follow-up data, 4 of 19 eyes (21%) with yeast infection, and 6 of 15 eyes (40%) with filamentary fungal infection. The number of eyes that had recurrent fungal infection after graft surgery could not be determined. A conjunctival flap was performed in three eyes (two with yeast infection), and three eyes with filamentary fungal infection were eviscerated. At the final follow-up, 11 of 34 eyes (32.4%) had a visual acuity of ⩾6/18, eight had an acuity between 6/24 and 6/60, and 15 eyes (44.1%) were <6/60. Five eyes, (15%) including the three eyes eviscerated, lost all vision. In the majority of cases, there were multiple pathologies associated with infection, and the primary cause of visual loss could not be determined. There was no evidence of an association between the type of infection and visual outcome (P=0.902).

Discussion

This prospective national survey provides a figure for the minimum incidence of fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom. The effect of under ascertainment from a failure to report cases could not be reliably estimated, and it was impossible to independently validate the isolates. For the purpose of this study, the criterion of a single positive identification rather than two was used, but the referring centre was also asked to confirm that the isolate was not considered to be a contaminant. Only a small percentage of isolates were sent to national reference laboratories for identification and sensitivity testing, and the principal reference laboratory kept a species-specific rather than a disease-specific database of referred isolates. Therefore, the possibility that some samples were misidentified cannot be excluded. These are shortcomings that would need to be addressed before any future study. The number of potential cases that were treated empirically without investigation during the study period is also unknown.

Despite collecting data for 2 years, the total number of cases was still relatively small and comparative data to validate our figure are unavailable. In a recent series of 65 patients seen at a single tertiary referral centre in London, an estimate of incidence could not be derived as the size of the referral population was unknown.13 The number of cases in this study was insufficient to allow a comparison of the several potential risk factors associated with infection between the two fungal groups, as well as the effect of treatment on outcome. Because of the small sample size our results should be considered as exploratory and further studies are required to confirm the reported associations.

More than half of the isolates reported in this series were species of the genus Candida. This confirms the importance of yeast as a cause of fungal keratitis in urbanised and temperate areas, with previous reports putting the proportion between 32 and 66% of cases.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Ocular surface disease was the most common risk factor for yeast infection, which has previously been reported as a major risk factor.1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16 Trauma and cosmetic contact lens wear were the major risk factors in patients with filamentary fungal infection.13 Male patients were more likely to have a filamentary fungal infection than a yeast infection, although, in contrast to previous studies, the mean age between the two groups was similar possibly because the majority of injuries in this series were not related to agriculture. Many eyes with ocular surface disease in this series had additional associated risk factors. Topical steroid and antibiotics have previously been suggested as risk factors for fungal keratitis,2, 9, 13, 17, 18, 19, 20 and topical steroid use is commonly reported before the onset of yeast infection, often to reduce the risk of rejection in eyes with a penetrating keratoplasty.7, 9, 21, 22 Topical steroid used to treat allergic conjunctivitis or herpetic keratitis is also a risk for fungal infection.2, 5, 9 Cosmetic contact lenses are a known risk for Fusarium fungal infection,23, 24 and two cases were identified in this series. Only one patient in this series was known to be HIV positive in contrast to a 21% of patients with fungal keratitis reported from New York.11

There is no agreed protocol for the treatment of suspected fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom, and a recent review of six randomised controlled trials, all performed in India or Bangladesh, did not demonstrate the superiority of any particular antifungal agent.25 Amphotericin 0.15% was the principal topical antifungal agent used in our series, followed by 1% econazole. Topical natamycin 5%, a commonly used drug for filamentary fungal infection in many countries, is not generally available for prescription in the United Kingdom. Fluconazole was the most frequently prescribed oral antifungal prescribed at the outset of treatment (31% of cases), including three cases with filamentary fungal infection, but voriconazole had been prescribed in 25% of 32 cases at final review. Although the proportion of eyes that required a penetrating keratoplasty was higher after filamentary fungal infection than after yeast infection, there was not a significant difference in visual outcome between groups at final review. The visual outcome was generally poor, with 44% of eyes having a final acuity <6/60. However, three of the five eyes that lost all vision were blind from their underlying disease. Because the associated pathologies and the acuities before the onset of keratitis were so dissimilar between groups, a comparison of the effect of the type of fungal infection on visual outcome was not attempted.

Corneal scarring from suppurative keratitis is a major cause of preventable blindness worldwide.26 In this case series, from a temperate and developed country, species of the genus Candida were the most common isolate and Aspergillus was the most common filamentary fungal isolate. Ocular surface disease was the risk factor that most frequently preceded yeast infection, but this was rare in cases that developed filamentary fungal infection. The majority of eyes with ocular surface disease had also been treated with topical steroid. It has been suggested that the incidence of fungal keratitis may be increasing as a result of clinical awareness, better diagnostic techniques, an increased use of broad spectrum topical antibiotics and topical corticosteroids, and cosmetic contact lens wear.2, 27, 28, 29, 30 Our study does not clarify this issue, although a future change in incidence could be identified by a repeat of this survey in the future.

References

Leck AK, Thomas PA, Hagan M, Kaliamurthy J, Ackuaku E, John M et al. Aetiology of suppurative corneal ulcers in Ghana and south India, and epidemiology of fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86: 1211–1215.

Thygeson P, Okumoto M . Keratomycosis: a preventable disease. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1974; 78: OP433–OP439.

Chin GN, Hyndiuk RA, Kwasny GP, Schultz RO . Keratomycosis in Wisconsin. Am J Ophthalmol 1975; 79: 121–125.

Foster CS . Miconazole therapy for keratomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1981; 91: 622–629.

Doughman DJ, Leavenworth NM, Campbell RC, Lindstrom RL . Fungal keratitis at the University of Minnesota: 1971–1981. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1982; 80: 235–247.

O’Day DM . Selection of appropriate antifungal therapy. Cornea 1987; 6: 238–245.

Kelly LD, Pavan-Langston D, Baker AS . Keratomycosis in a New England referral center: spectrum of pathogenic organisms and predisposing factors. In: Bialasiewicz AA, Schaal KP (eds). Infectious diseases of the eye. Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, 1994, pp 184–190.

Griffiths MFP, Clayton YM, Dart JKG . Antifungal sensitivity testing of keratitis isolates at Moorfields Eye Hospital 1975–1990: therapeutic implications. In: Bialasiewicz AA, Schaal KP (eds). Infectious diseases of the eye. Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, 1994, pp 190–194.

Tanure MA, Cohen EJ, Sudesh S, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR . Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea 2000; 19: 307–312.

Rondeau N, Bourcier T, Chaumeil C, Borderie V, Touzeau O, Scat Y et al. Fungal keratitis at the Centre Hospitalier National d’Ophtalmologie des Quinze-Vingts: retrospective study of 19 cases. J Fr Ophtalmol 2002; 25: 890–896.

Ritterband DC, Seedor JA, Shah MK, Koplin RS, McCormick SA . Fungal keratitis at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary. Cornea 2006; 25: 264–267.

Bhartiya P, Daniell M, Constantinou M, Islam FM, Taylor HR . Fungal keratitis in Melbourne. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2007; 35: 124–130.

Galarreta DJ, Tuft SJ, Ramsay A, Dart JK . Fungal keratitis in London: microbiological and clinical evaluation. Cornea 2007; 26: 1082–1086.

Foot B, Stanford M, Rahi J, Thompson J . The British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit: an evaluation of the first 3 years. Eye 2003; 17: 9–15.

http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_population/PT118_V1.pdf Office for National Statistics. accessed 15 March 2008, 2008.

Ross HW, Laibson PR . Keratomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1972; 74: 438–441.

Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Athmanathan S, Rao GN . The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: a 10-year review at a referral eye care center in South India. Cornea 2002; 21: 555–559.

Chowdhary A, Singh K . Spectrum of fungal keratitis in North India. Cornea 2005; 24: 8–15.

Liesegang TJ, Forster RK . Spectrum of microbial keratitis in South Florida. Am J Ophthalmol 1980; 90: 38–47.

Berson EL, Kobayashi GS, Becker B, Rosenbaum L . Topical corticosteroids and fungal keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol 1967; 6: 512–517.

Harris Jr DJ, Stulting RD, Waring III GO, Wilson LA . Late bacterial and fungal keratitis after corneal transplantation. Spectrum of pathogens, graft survival, and visual prognosis. Ophthalmology 1988; 95: 1450–1457.

Fong LP, Ormerod LD, Kenyon KR, Foster CS . Microbial keratitis complicating penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology 1988; 95: 1269–1275.

Alfonso EC, Cantu-Dibildox J, Munir WM, Miller D, O'Brien TP, Karp CL et al. Insurgence of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear. Arch Ophthalmol 2006; 124: 941–947.

Khor WB, Aung T, Saw SM, Wong TY, Tambyah PA, Tan AL et al. An outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wear in Singapore. JAMA 2006; 295: 2867–2873.

FlorCruz NV, Peczon Jr I . Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 23 (1): CD004241.

Whitcher JP, Srinivasan M, Upadhyay MP . Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 214–221.

Rosa Jr RH, Miller D, Alfonso EC . The changing spectrum of fungal keratitis in south Florida. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 1005–1013.

Foster CS . Fungal keratitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1992; 6: 851–857.

Johns KJ, O’Day DM . Pharmacologic management of keratomycoses. Surv Ophthalmol 1988; 33: 178–188.

Thomas PA . Fungal infections of the cornea. Eye 2003; 17: 852–862.

Acknowledgements

We thank Suzanne Cabral for help with the administration of this study. We also thank all our colleagues who reported cases for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

SJ Tuft received a grant from the Iris fund for the administration of this project

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tuft, S., Tullo, A. Fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom 2003–2005. Eye 23, 1308–1313 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.298

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.298

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Antifungal susceptibility profiles for fungal isolates from corneas and contact lenses in the United Kingdom

Eye (2024)

-

Utility of investigation for suspected microbial keratitis: a diagnostic accuracy study

Eye (2023)

-

Filamentous Fungal Keratitis in Greece: A 16-Year Nationwide Multicenter Survey

Mycopathologia (2022)

-

Das Deutsche Pilz-Keratitis-Register

Der Ophthalmologe (2019)

-

Fungal keratitis in the Republic of Ireland

Eye (2017)