Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Majority of neonates in developing countries are born at home and most neonatal deaths occur without receiving medical care. This retrospective analysis was undertaken to develop simple clinical criteria for use in rural community to identify neonates at risk of death.

STUDY DESIGN:

By analyzing the observational data on two cohorts of neonates in 39 villages in different years of the Gadchiroli field trial, we selected a minimum set of clinical features. We evaluated this set for its sensitivity, specificity and predictive value to detect eventual neonatal death, the primary study outcome.

RESULTS:

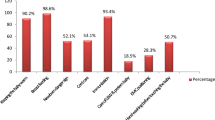

The cohorts included 763 neonates with 40 deaths in 1995 to 1996, a year with minimum interventions, and 1598 neonates with 38 deaths in 1996 to 1998, the years of intensive interventions. On the day of birth, presence of any one of the three: (1) birth weight <2000 g, (2) preterm birth or (3) baby not taking feeds; or, during the rest of neonatal life, mother's report of reduced or stopped sucking by baby, were identified as the predictors of neonatal deaths. The combined set gave a sensitivity of 95%, specificity, 77.3%; predictive value, 18.8%; and the yield, 26.5% in 1995 to 1996 and, respectively, 86.8, 78, 8.8, and 23.5% in 1996 to 1998. The mean lead time gained was 3.4 to 6.6 days.

CONCLUSION:

Presence of any one of the four predictors will identify with high sensitivity and moderate specificity nearly a quarter of the neonates in rural community as high risk, 3.4 to 6.6 days in advance, for intensive attention at home or referral.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Save the Children. State of the World's Newborn. Washington, DC: Save the Children; 2001.

National Family Health Survery II (1998–1999). International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai, India, 2000.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Mornkar VP, Sontakke PG, Solanki JM . Pneumonia in neonates: can it be managed in the community? Arch Dis Child 1993;68:550–556.

Bhandari N, Bahl R, Bhatnagar V, et al. Treating sick young infants in urban slum setting. Lancet 1996;347:1774–1775.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule S, Deshmukh M, Reddy MH . Burden of morbidities and the unmet need for health care in rural neonates — a prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. Indian Pediatr 2001;38:952–965.

Morrison AS . Screening. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincot-Raven Publishers; 1998.

Gove S, for the WHO Working Group on Guidelines for Integrated Management of Sick Children. Integrated management of childhood illness by outpatient health workers: technical basis and overview. Bull World Health Organ 1997;75 (Suppl 1):7–24.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule S, Reddy MH, Deshmukh M . Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet 1999;354:1955–1961.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM, et al. Methods and the baseline situation in the field trial of home-based neonatal care in Gadchiroli, India. J Perinatol 2005;25:S11–7.

Bang AT, Reddy HM, Baitule SB, Deshmukh MD, Bang RA . The incidence of morbidities in a cohort of neonates in rural Gadchiroli, India: seasonal and temporal variation and the scope for prevention. J Perinatol 2005;25:S18–28.

Bang AT, Paul VK, Reddy HM . Why do neonates die in rural Gadchiroli, India? Part I. J Perinatol 2005;25:S29–34.

WHO Collaborative Study of Birth Weight Surrogates. Use of a simple anthropometric measurement to predict birth weight. Bull World Health Organ 1994;71 (2):157–163.

Raymond EG, Tafari N, Troendle JF, Clemens JD . Development of a practical screening tool to identify preterm, low birth weight neonate in Ethiopia. Lancet 1994;344:520–523.

Daga SR, Daga AS, Patole S, Kadam S, Mukadam Y . Foot length measurement from foot print for identifying a newborn at risk. J Trop Pediatr 1988;34:16–19.

World Health Organization. Post-Partum Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The financial support for this work came from The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation and Saving Newborn Lives Initiative, Save the Children, USA, and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reddy, M., Bang, A. How to Identify Neonates at Risk of Death in Rural India: Clinical Criteria for the Risk Approach. J Perinatol 25 (Suppl 1), S44–S50 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211272

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211272

This article is cited by

-

Low Birth Weight and Preterm Neonates: Can they be Managed at Home by Mother and a Trained Village Health Worker?

Journal of Perinatology (2005)

-

Home-Based Neonatal Care: Summary and Applications of the Field Trial in Rural Gadchiroli, India (1993 to 2003)

Journal of Perinatology (2005)