Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article was to study the clinical features, pathogenic organisms, and the outcome in cases of infectious scleritis.

Method

Retrospective chart review of all patients of infectious scleritis examined from January 2000 to February 2005 in the cornea services of L.V. Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India was done. Information including patient's age, predisposing factors, clinical presentation, pathogenic organism, methods of diagnosis, treatment, and outcome were abstracted from the medical records.

Results

A total of 21 eyes of infectious scleritis were identified. All except three eyes had preceding predisposing factors, prior cataract surgery (6 eyes) (30%) and pterygium surgery (5 eyes) (23.8%) were the most common predisposing factors. Fungus (8 eyes) (38%), either alone (5 eyes) (24%) or as mixed infection (3 eyes) (14%), was the most common offending organism. Nocardiawas identified in five eyes (24%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosain two eyes (10%). Seven eyes (33%) had accompanying corneal infiltration. Multifocal scleral abscess was seen in three eyes (14%) and endophthalmitis was seen in three eyes (14%). During the course of treatment, five eyes (24%) were complicated by serous retinal or choroidal detachment and five eyes (24%) with progression of cataract. Surgical debridement was carried out in 14 eyes (67%). Four eyes (19%) were eviscerated. Useful vision, defined as visual acuity ≥20/200, could be preserved with treatment in seven eyes (33%).

Conclusion

Although predisposing factors were similar, fungi and Nocardiawere the most common etiological agents in this series and the clinical outcomes were poorer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scleritis, an inflammatory disorder of sclera, is often due to immunological phenomena. In nearly 40–50% patients, this is associated with systemic collagen vascular diseases. Infectious scleritis is a rare entity and accounts for just 5–10% of all cases of scleritis.1, 2, 3 However, the initial clinical picture of infectious scleritis may be identical to that caused by immune-mediated scleritis. Therefore, in a patient presenting with scleritis, an infectious etiology is usually not suspected, which may result in an unusual delay in the diagnosis. Infectious scleritis may follow accidental or surgical trauma, severe endophthalmitis, or may occur as an extension of a primary corneal infection.4 Conjunctival and possible tear film alterations expose the underlying necrotic scleral collagen to microorganisms, thereby allowing them to localize, adhere, colonize, and invade the tissues. In addition, some infectious agents such as Mycobacteria and Treponema may cause an immune-mediated inflammatory microangiopathy and thereby indirectly lead to scleritis.5

Although a variety of organisms have been identified as the cause of infective scleritis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been the most commonly reported causative agent in various series.6, 7, 8 In the earlier series, the clinical outcomes were reported to be poor and most cases required enucleation or evisceration. A review of more recent reports clearly suggests that infectious scleritis can be managed successfully with preservation of vision as a result of combined antibiotic therapy and early surgical intervention.6, 7, 8 Surgical debridement not only facilitates the penetration of antibiotics but also debulks the infected scleral tissue. Since most of these reports are from countries where bacterial infections of eye are otherwise common, we hypothesized that based on the experience with microbial keratitis; etiological agents may be different in geographic regions with tropical climate. In the present communication, we highlight the differences in etiology and outcome of the cases of infectious scleritis, compared to the prior reported data.

Methodology

All patients of infectious scleritis examined in the cornea services of L.V. Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India from January 2000 to February 2005 were included in this study. The criteria for the diagnosis of infectious scleritis were the presence of single or multiple ulcerated or non-ulcerated, inflamed scleral nodules that revealed microorganisms either on microbiology or histopathology evaluation. A total of 21 patients met these inclusion criteria. Patients presenting with ulcerative lesions underwent a detailed microbiology workup that consisted scleral scrapings from the base of the active lesion for microscopic examination as well as culture on blood and chocolate agar, brain–heart infusion broth, thioglycolate broth, non-nutrient agar with an overlay of Escherichia coli, and Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Details of microbiology workup have been published in our previous publication.9 Patients presenting with non-ulcerative lesions, and where an infectious etiology was strongly suspected were subjected to scleral scraping in the operating room after de-roofing the nodular lesion by dissecting overlying conjunctiva. Initial therapy was based on either the clinical suspicion or results of microscopic examination of smears. Treatment was later modified depending on the clinical response and the results of culture and sensitivity. The medical management included topical and systemic antibiotics and surgical debridement was performed as indicated to remove the infected necrotic tissue and facilitate antibiotic penetration. Screening was done in all the patients to rule out collagen vascular diseases. Information including patient's age, the predisposing factors, pathogenic organisms, clinical presentation, methods of diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes were abstracted from the medical records.

Results

A total of 21 patients (21 eyes) were included in this study. Demographic data and clinical details of these cases are given in Table 1.

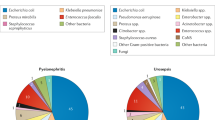

The age of these patients ranged between 6 and 80 years. Male to female ratio was 6 : 1. All except three eyes (14%) had preceding history of surgical or accidental injury. None of the patients had any debilitating ocular or systemic disease except for case 7, who was a known diabetic. Cataract surgery was a predisposing factor for infectious scleritis in six eyes (30%) (95% confidence interval (CI), 10–48%) followed by pterygium excision in five eyes (24%) (95% CI, 6–42%) and scleral buckling in three eyes. Because the surgeries were performed elsewhere, preoperative and operative details of these cases were not available in the medical records of the institute. The latency period between the time of cataract surgery and the onset of infectious scleritis ranged from 1 month to 4 years, and between pterygium excision and infective scleritis from 1 month to 3 years. Three patients had incurred ocular trauma, 1 month to 1 year prior to the onset of infective scleritis. The various organisms isolated from these cases are shown in Table 1 (Figure 1a–d). Fungus, (8 eyes) (38%) (95% CI, 17–59%) either alone (5 eyes) (24%) or as mixed infection (3 eyes) (14%) was the most common offending organism in this series. Nocardia was identified in five eyes (24%), Corynebacterium diphtheria in three eyes (14%), P. aeruginosa in two eyes (10%), and Streptococcus pneumoniae in one eye (5%). At presentation, seven cases (33%) had associated corneal involvement. Corneal infection was contiguous with the scleral lesion in all cases. Corneal infiltrate was of full thickness and there was associated severe anterior chamber reaction. There was no difference in predisposing factors or etiological agents in these cases as compared to those without corneal involvement. An ulcerative scleral lesion was the most common presentation in this series. In addition, three eyes presented with multifocal scleral abscesses, and three eyes (14%) had associated endophthalmitis at presentation.

(a) Clinical photograph of a 63-year-old male patient with a scleral ulcer in the left eye caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, one month after scleral buckling surgery (patient 1). (b) A 55-year-old female presented with multifocal scleral abscess in her left eye caused by A. fumigatus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 4 years after cataract surgery, (patient 7). (c) Clinical photograph of a 62-year-old male patient with a scleral and corneal ulcer in the left eye caused by Nocardia asteroides (patient 9). (d) Clinical photograph of a 50-year-old male patient with a scleral and a corneal ulcer in the right eye caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, one month after pterygium surgery (patient 13).

Treatment details of these cases are given in Table 1. Fungal scleritis cases were treated with topical natamycin 5% eye drops supplemented with systemic itraconazole 100 mg two times per day. Nocardia scleritis cases were treated with topical amikacin and a systemic trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole combination. The treatment of fungal and Nocardia scleritis cases had to be continued for an average duration of 5–6 months. Surgical debridement was performed in 14 eyes (67%). The surgical debridement was diagnostic in cases with nodular lesion or those with negative microbiology on initial scraping. This also facilitated debulking of the infected scleral tissue and improved the drug penetration. During the surgical debridement, the actual area of involvement was usually found to be larger than the visible lesion on biomicroscopic view.

During the course of treatment, five eyes (23.8%) were complicated by serous retinal or choroidal detachment and five eyes (23.8%) with progression of cataract. Four eyes (19%) were eventually eviscerated (all these eyes had fungal scleritis), 3 of these 4 eyes had associated endophthalmitis and one had multifocal scleral abscess. Comparison of fungal with other scleritis cases is shown in Table 2. Infection resolved in 17 eyes but useful vision (better than or equal to 20/200) was regained only in 7 eyes (33%).

Discussion

Necrotizing scleritis, generally associated with autoimmune vasculitic diseases, tuberculosis, or syphilis, is a devastating ocular disorder. All these cases require treatment with systemic corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive agents that may worsen infectious scleritis. Therefore, it is important to make an early diagnosis of infectious scleritis. Infectious scleritis should be suspected in any case of indolent progressive scleral necrosis with suppuration, especially if there is a history of accidental or surgical trauma. Faulty surgical technique and trauma cause destruction of conjunctival and episcleral tissue and their vasculature, predisposing to direct scleral invasion by organisms. In addition, inflammatory microangiopathy response in vessels induced by microbial agents may perpetuate the condition. It is unusual for the operative site to be infected after a long and silent postoperative period without any other occurrence. Survival of organisms in the tissue for this period of time is unlikely. For these cases, the trigger mechanism is still unknown for the development of infectious scleritis after a long latent period. But it is well established that necrotizing scleritis (SINS) can be activated long after surgery.10 The mechanism which induces SINS may be a prodromal factor in inducing the infectious scleritis. It had been postulated by Lin et al6 that probably after the initiation of SINS, the microorganisms invaded and caused the late onset postsurgical infectious scleritis. However, unlike the high prevalence of vasculitis among patients of SINS, none of our patients had any systemic disorder.10 Similar experience has been reported by Altman et al,11 in their series of four cases of infectious scleritis by S. pneumoniae. Two of the four patients developed scleritis 4 and 13 years after the prior surgeries and it was suspected that an underlying SINS became super-infected. Both these patients were negative for collagen vascular diseases.

Although various organisms have been identified as the cause of infectious scleritis, P. aeruginosa remains the leading responsible organism in reported literature.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Fungal scleritis was a rare entity. Huang et al reported 16 cases of infective scleritis, of which three were fungal (18%). Lin et al6 reported 30 patients of infectious scleritis of which only one had fungal keratitis (3%). In a series by Hsio et al,7 only one case had fungal etiology (5%) out of the total 18 cases of infectious scleritis. Unlike these previous reports, fungus in our series was the most common offending organism (38%), probably due to geographic areas with a hot and humid climate. At the L.V. Prasad Eye Institute, among the 3399 patients with culture-proven infectious keratitis cases examined from February 1991 to June 2001, 1352 (39.8%) patients were diagnosed as having fungal keratitis.12 The increased incidence of fungal infections over a major part of the year in India may be attributable to the enormous amount of fungal spores prevalent in the environment.12

Fungal scleritis usually occurs as an exogenous infection; occasionally, however, it may result from the hematogenous spread of systemic fungal disease.13 Stenson et al13 reported a case of endogenous fungal scleritis in an intravenous drug abuser. In our series, all cases of fungal scleritis had a preceding predisposing surgical or accidental trauma. None of the patients had any debilitating ocular or systemic disease predisposing for endogenous scleritis except for case 7, who was a known diabetic. Aspergillus flavus was the most common fungus isolated in these cases. Three cases of fungal scleritis had associated corneal infiltration (case no. 3, 6, and 18) and three had associated endophthalmitis (cases no. 3, 5, and 18).

Nocardia was the next common microorganism isolated from this series. Review of literature using PubMed and search using term ‘infective scleritis’ revealed that even this organism is a rare cause of scleritis.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 High prevalence in the current series could be due to the higher presence of Nocardia in the soil of India. Also, India being an agricultural-based developing economy, has led to greater opportunities for transfer of these organisms from the soil to the eye.19

Nocardia belongs to the order Actinomycetales. It is a Gram positive, weakly acid-fast, filamentous saprophyte representing the indigenous microflora of soil and decaying vegetation. Nocardia are not a normal part of the ocular flora. The mode of infection is normally by implantation or seeding of the organisms from the soil due to preceding trauma or a foreign body and run a slow chronic clinical course. In our cases, an antecedent history of previous ocular surgery or trauma was present in three cases. Corticosteroids are known to worsen the infection, probably by stabilizing and inhibiting the release of lysosomal enzymes thereby preventing the destruction of phagocytosed intracellular Nocardial organisms. High doses of both topical and systemic antibiotics were necessary to halt the progression of infection by this organism. While literature review suggests a variable response to medical, surgical, and combined treatment regimes, all patients in our series responded favourably to treatment.14, 15, 16, 17, 18

As recommended for severe scleritis refractory to medical treatment, surgical debridement and irrigation of the exposed scleral bed with antibiotics were performed in this series in 14 cases. Surgical debridement not only facilitates the penetration of antibiotics but also debulks the infected scleral tissue. Lin et al6 reported favourable outcomes in 26 cases of infectious scleritis that underwent surgical debridement. Hsio et al7 also reported similar outcomes in their series of 18 patients of infective scleritis.

In our series, the overall outcome of treatment in spite of surgical debridement was not very good; the infection resolved in 15 of 21 cases. Even in these cases, useful vision, defined as vision better than 20/200, could be achieved in seven (33%) cases only. All these resolved cases had bacterial etiology except for one case of fungus. Vision could not be salvaged in remaining cases of fungal scleritis. Review of literature using PubMed revealed that outcome of fungal scleritis is usually poor.6, 7, 8, 20, 21, 22 Huang et al reported 16 cases of infective scleritis, of which three were fungal, two of these cases required enucleation, and the last one developed recurrence in a patch graft. Similar poor outcome of fungal scleritis was reported by Lin et al6 and Hsio et al.7 Numerous factors could be responsible for progressive worsening in fungal scleritis; these are poor penetration of antifungal agents in avascular sclera, nonavailability of fungicidal agent, and the ability of organisms to persist in the avascular interstitial scleral lamellae for prolonged periods without inciting an inflammatory response, leading to progressive worsening. Moriarty et al23 reported presence of fungal hyphae in enucleated specimens from two patients, in spite of the prolonged treatment.

Further, infective scleritis can be complicated by formation of cataract, glaucoma, endophthalmitis, and exudative choroidal and retinal detachment. These sequelae are at least partially responsible for poor visual outcomes seen in our series in cases of resolved scleritis. The high percentage of these complications was probably due to prolonged and severe infection and inflammation. Further, the actual intraocular spread of infective agent may lead to infective endophthalmitis. In our series, endophthalmitis developed in three eyes, all of which were eventually eviscerated. All three of these eyes had fungal scleritis (case no. 3, 5, and 18).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate the high frequency of fungal scleritis among infective scleritis patients. Most of these patients had poor anatomical and visual outcomes. Nevertheless, early diagnosis, appropriate antimicrobial therapy, and timely surgical debridement are essential to shorten the course of treatment and improve the final outcome of infective scleritis.

As with all retrospective studies, our results must be interpreted cautiously. Our series is one from a tertiary care practice and not a population-based study. As such, there is the potential for ascertainment bias and towards patients with more unusual or difficult-to-control disease.

References

Jabs DA, Mudun A, Dunn JP, Marsh MJ . Episcleritis and Scleritis; clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 130: 469–476.

Sainz de la Maza M, Jabbur NS, Foster CS . Severity of scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 389–396.

Tuft SJ, Watson PG . Progression of scleral disease. Ophthalmology 1991; 98: 467–471.

Reynolds MG, Alfonso E . Treatment of infections Scleritis and keratoscleritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1991; 112: 543–547.

Foster CS, Sainz de la Maza M . The Sclera: Infections Scleritis. Springer-Verlag New York, 1994; 242–277.

Lin CP, Shih MH, Tsai MC . Clinical experience of infections scleral ulceration: a complication of pterygium operation. Br J Ophthalmol 1997; 81: 980–983.

Hsiao CH, Chen JJ, Huang SC, Ma HK, Chen PY, Tsai RJ . Intrascleral dissemination of infectious scleritis following pterygium excision. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82: 29–34.

Huang FC, Huang SP, Tseng SH . Management of infections scleritis after pterygium excision. Cornea 2000; 19: 34–39.

Sharma S, Kunimoto DY, Gopinathan U, Atmanathan S, Garg P, Rao GN . Evaluation of corneal scraping smear examination methods in the diagnosis of bacterial and fungal keratitis: a survey of eight years of laboratory experience. Cornea 2002; 21: 643–647.

O' Donoghue E, Lightman S, Tuft S, Watson S . Surgically induced necrotising sclerokeratitis- precipitating factors and response to treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76: 17–21.

Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Atmanathan S, Rao GN . The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: a 10-year review at a referral eye care center in South India. Cornea 2002; 21: 555–559.

Altman AJ, Cohen EJ, Berger ST, Mondino BJ . Scleritis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Cornea 1919; 10: 341–345.

Stenson S, Brookner A, Rosenthal S . Bilateral endogenous necrotizing scleritis due to Aspergillus Oryzae. Ann Ophthalmol 1982; 14: 67.

Brooks JGJ, Mills RAD, Coster DJ . Nocardia scleritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 114: 371–372.

Basti S, Gopinathan U, Gupta S . Nocardia necrotizing scleritis after trauma. Cornea 1994; 13: 274–275.

Knox CM, Whitcher JP, Cevellos V, Margolis TP, Irvine AR . Nocardia scleritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1997; 123: 713–714.

Choudhry S, Rao SK, Biswas J, Madhavan HN . Necrotizing Nocardia scleritis with intraocular extension: a case report. Cornea 2000; 19: 246–248.

Sridhar MS, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ, Lister MA, Laibson PR . Nocardia asteroids sclerokeratitis in a contact lens wearer. CLAO J 2002; 28: 16–18.

Haripriya A, Lalitha P, Mathen M, Prajna NV, Kim R, Shukla D et al. Nocardia endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: clinicomicrobiological study. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 139: 837–846.

Lincoff HA, McLean JM, Nano H . Scleral abscess: I. A complication of retinal detachment buckling procedures. Arch Ophthalmol 1965; 74: 641.

Milouskas AT, Duke JR . Mycotic scleral abscess: report of a case following a scleral buckling operation for retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol 1967; 63: 951.

Margo CE, Polack FM, Mood CI . Aspergillus panophthalmitis complicating treatment of pterygium. Cornea 1988; 7: 285.

Moriarty AP, Crawford GJ, McAllister IL, Constable IJ . Severe corneoscleral infection. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111: 947–951.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was funded by Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation. The authors have no financial interest or any conflicting relationship in any of the issues or products referred in the manuscript

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jain, V., Garg, P. & Sharma, S. Microbial scleritis—experience from a developing country. Eye 23, 255–261 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6703099

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6703099

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A novel technique of full-thickness scleral debridement in fulminant necrotising infectious scleritis and its outcomes—a consecutive case series

International Ophthalmology (2022)

-

Candida albicans scleral abscess in a HIV-positive patient and its successful resolution with antifungal therapy—a first case report

Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection (2016)