Abstract

Purpose

To determine the incidence of glaucomatous progression at mean intraocular pressure (IOP) levels in patients with ocular hypertension (OHT).

Methods

A retrospective, multicentre, cohort analysis of 230 OHT patients with 5 years of follow-up evaluated for risk factors associated with progressive optic disc and visual field loss to determine the incidence of glaucomatous progression.

Results

Forty percent of patients with IOPs ⩾24 mmHg, 18% of patients with IOPs of 21–23 mmHg, 11% of patients with IOPs with 18–20 mmHg, and 3% of patients with IOPs of ⩽17 mmHg progressed to glaucoma. The mean IOP was 19.8±2.4 mmHg in the stable group and 21.7±2.6 mmHg in the progressed group (P=0.0004). The highest average peak IOP was 23.4±4.0 mmHg in the stable group and 25.2±3.1 mmHg in the progressed group (P=0.006). Based on the pachymetry values for central corneal thickness, patients with thinner corneas more often progressed to glaucoma (P<0.0001). A multivariant regression analysis to determine risk factors for progression was positive primarily for higher peak IOPs, older age, male gender, argon laser trabeculoplasty, visual acuity ⩾20/50, and no topical medical therapy or β-blocker therapy prior to the study.

Conclusions

IOP reduction within the normal range over 5 years of follow-up reduces the chance of progression to primary open-angle glaucoma in OHT patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) showed that the reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP) in patients with ocular hypertension (OHT) may help prevent glaucomatous progression.1 In addition, by multivariant analysis this trial indicated several risk factors that help physicians identify patients more likely to progress, including advancing age, higher IOPs, wider cup/disc ratios, and thinner corneas.

Although the OHTS trial indicated the importance in reducing the IOP in general, it did not provide specific mean pressures that prevent progression to primary open-angle glaucoma. In addition, it did not show when, and in which ocular hypertensive patients, treatment should be initiated. Unfortunately, little information currently exists that provides specific target pressures to help a physician know when to initiate therapy, and the extent to which an ocular hypertensive patient should be treated to prevent progression to open-angle glaucoma.

The purpose of this trial was to evaluate a 5-year follow-up of patients with OHT to determine risk factors for progression and the appropriate treatment target pressures that could help prevent progression to glaucoma.

Methods and materials

Patients

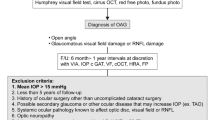

This retrospective trial was conducted in seven centres from seven primary investigators who were each fellowship-trained glaucoma subspecialists. Patients included in this study were ⩾22 years of age at Visit 1 and had a clinical diagnosis of OHT (non-glaucomatous visual field and optic disc findings) in at least one eye (study eye) at Visit 1. Also included were patients who had been treated with at least 5 years follow-up (unless progression to glaucoma occurred) and had no closed angle component as a mechanism for their pressure elevation.

Patients were excluded who had: abnormality preventing reliable applanation tonometry in the study eye; opacity or patient uncooperativeness that restricted adequate examination of the ocular fundus or anterior chamber in the study eye; poor follow-up (less than six visits with IOP measured by Goldmann applanation tonometry over 5 years (non-progressed patients only)); no reliable baseline visual field and optic disc exam within 12 months before or within 6 months after Visit 1; and a diagnosis of a primary or secondary glaucoma, including exfoliation glaucoma.

In general, OHT was defined by an IOP of ⩾22 mmHg and a normal appearing optic nerve head and visual field associated with an open and normal appearing anterior chamber angle. Progression to glaucoma was typically diagnosed by the development of glaucomatous visual field loss and/or glaucomatous optic nerve head cupping.

Methods

Patients were chosen for this study from consecutively reviewed charts from the practices of the study investigators. Data collection began from the patient's initial examination by the investigator or the initial diagnosis of OHT made by the investigator. However, initial IOPs from patients requiring immediate treatment were excluded from analysis until they were stabilized to a level suitable for long-term follow-up. Data were recorded from each available visit included in the follow-up period. Data were gathered from the stable OHT group for 5 years following the initial visit with the investigator. In contrast, data were collected from the records of progressed patients only until the time glaucoma was diagnosed, so the information included in this study would reflect the ocular condition that progressed to glaucoma.

The following baseline information was collected retrospectively from the patients' charts: date of visit, age, race, gender, medications to reduce IOP, surgeries to treat OHT, IOP, visual acuity, baseline optic disc exam, baseline automated perimetry, and central corneal thickness (collected at any time during the 5-year follow-up period) as well as the optic disc status characterized by ‘normal’ (no other option available at Visit 1) or ‘glaucomatous findings,’ and automated perimetry characterized by ‘no glaucomatous changes’ (no other option available at Visit 1) or ‘glaucomatous changes.’

Data collected during the follow-up period were IOP, visual acuity, central corneal thickness (if not measured previously), medications to reduce IOP, glaucoma surgeries, and date of each visit. Each investigator determined progression to glaucoma based on visual field and optic disc status of the patient. In general, changes that would lead to a diagnosis of glaucoma were the development of neural rim thinning, a disc haemorrhage, or a nerve fiber layer defect and/or the initiation of a visual field defect within the arcuate area. In each case, progression must have been noted in the chart with the associated clinical changes. Patients without ‘progression’ noted were assumed to be stable.

Statistics

PRN Pharmaceutical Research Network, LLC, analysed the data. The primary safety variable, the incidence of glaucomatous progression, was described by the number of patients progressed and non-progressed at each mean IOP level and by corneal thickness as measured by contact corneal pachymetry. Corneal thickness was subdivided into the thinnest, thickest, and middle-third as determined by the central corneal pachymetry measurement. The division between the three levels of corneal thicknesses was performed subjectively to attempt to isolate the range of thin corneas with the greatest incidence of progression compared to the range of thick corneas with the lowest incidence of progression. The corneal levels were divided in this fashion to help isolate the level of corneal thickness that would be more often associated with progression to glaucoma. The OHTS trial had previously found generally that thin corneas were a risk factor to develop glaucoma.1

The following variables were compared by a Student's unpaired t-test for progressed and non-progressed patients: age, average number of visits per year, average number of visits in the study, average and peak IOP as well as the associated standard deviation over time, number of medicines at the end of the study and study term.2 Country, gender, study eye, glaucoma medicine, and ophthalmic surgeries (both at baseline and during follow-up) were evaluated by a Fisher's exact test or χ2 test as appropriate. Visual acuity and optic disc at baseline were evaluated by a Mann–Whitney U-test. Cause for progression was not evaluated statistically.

A multivariant regression analysis was run to determine treatment effectiveness related to both progression and mean IOP level over the 5 years of follow-up.

Results

Patient characteristics

We included in this study 230 patients with OHT from seven separate clinical sites in Spain, Turkey, Slovenia, Russia, the United States, Greece, and Hungary. The number of progressed patients was 32 (14%) and of stable patients was 198 (86%). The stable group had an average of 10.2±3.5 visits per patient over 5.1±1.1 years and the progressed group had 6.8±3.1 visits over 3.0±1.1 years (P<0.0001).

Baseline patient characteristics at the beginning of the follow-up period are shown in Table 1. At study baseline, progressed patients demonstrated a higher average age (P=0.002), were more often male (P=0.01), and had a larger cup/disc ratio (P=0.008) than patients who remained stable. No baseline differences between groups were noted for the eye included in the study, visual acuity, or laser trabeculoplasty (P>0.05). Table 2 shows the topical medicines at baseline. At baseline no differences between groups were noted for classes of glaucoma medications, except the stable group had more patients treated with β-blockers (P=0.02). In addition, more patients who were untreated were in the progressed group (P=0.01). The mean IOP at baseline for treated patients was 20.1±3.7 mmHg and for untreated patients was 22.1±3.0 mmHg (P<0.0001). The mean pressure for all patients at baseline was 20.8±3.6 mmHg.

Patient follow-up

In the Figure 1, the number of progressed and stable patients at each level of mean IOP is shown. Forty percent of patients with pressures ⩾24 mmHg (n=10 of 25), 18% of patients with mean pressures of 21–23 mmHg (n=12 of 65), 11% of patients with pressures of 18–20 mmHg (n=9 of 106), and 3% of patients with pressures of ⩽17 mmHg progressed (n=1 of 34) to glaucoma.

Follow-up characteristics are shown in Table 3. Both the overall mean (P=0.0004) and mean peak (P=0.006) IOPs were higher in the progressed compared to the stable group. However, the mean standard deviation for the IOP was not significantly higher in the progressed than the stable group (P=0.8). Laser trabeculoplasties were statistically more common in the progressed group (P=0.04) No other statistical differences were observed between groups including the number of medicines at study end, the class of medication treatment during follow-up or the incidence of cataract, and trabeculectomy surgeries (P>0.05). Most patients who were diagnosed with glaucomatous progression demonstrated changes in both their optic disc and visual field together.

Based on the pachymetry values for central corneal thickness, patients with thinner corneas more often progressed to glaucoma (P<0.0001, Table 4). In addition, statistical differences were observed between groups for a higher average number of visits per year (P=0.04) and the incidence of laser trabeculoplasty (P=0.04) in progressed patients. No differences in corneal thickness were found based on gender (P=0.86) or patient age (P=0.33).

The multivariant regression analysis showed numerous risk factors for progression, including higher peak IOPs, older age, male gender, argon laser trabeculoplasty, and visual acuity ⩾20/50, as well as no topical medical therapy and no β-blocker therapy prior to the study. A complete list of statistically significant values is shown in Table 5.

Discussion

Controversy still exists over the proper treatment end points of patients with glaucoma. Several historical and recent studies have demonstrated not only the benefit of IOP reduction in primary open-angle glaucoma, but have indicated specific target pressures that help prevent progressive glaucomatous damage. These reports have shown that IOPs of between 13 and 18 mmHg over 5 years helped prevent glaucomatous progression with approximately 5–15% of patients with primary open-angle, and 28% with exfoliation glaucoma worsening over 5 years.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Several studies, however, have indicated a further benefit in advanced glaucoma patients of pressures as low as 12–13 mmHg.6, 10, 11

In contrast, generally IOPs above 18 mmHg have led to greater incidences of progressive glaucomatous damage. For example, in several reports patients with slightly higher mean pressures (19–21 mmHg) progressed in approximately 50–67% of cases, and progression occurred with pressures ⩾22 mmHg in almost 100% of patients.3, 13 However, the level of mean or peak pressures that would provide safety for all patients with primary open-angle glaucoma has not yet been defined clearly.10

In addition, prior studies by both Medeiros et al15 and Herndon et al14 have indicated that a thin cornea was a risk factor for progression in glaucoma patients.14, 15 Accordingly, Stewart et al16 recently evaluated target pressures based on corneal thickness in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. They found that patients with thinner corneas (⩽510 μm) progressed more often than those with thicker corneas. The level of IOP, however, that kept patients with thinner corneas stable (⩽17 mmHg) was no different than for those with thicker corneas.

The purpose of this trial was to evaluate retrospectively a 5-year follow-up of patients with OHT to determine risk factors for progression and appropriate treatment target pressures that might help preserve long-term vision.

This study helped confirm the results of the OHTS trial by indicating that ocular hypertensive patients, over 5-years of follow-up, are less likely to progress to glaucoma with a lower IOP. Patients at mean IOP levels of ⩾24 mmHg progressed to glaucoma in 40% of cases. However, patients with progressively lower pressures progressed less often. At mean pressures of 21–23 mmHg patients worsened in 21% of cases, at pressures of 18–20 mmHg in 9% of cases, and at pressures of 14–17 mmHg in only 3% of cases.

The information in this paper is additive to the OHTS because it helps the physician understand the chance of progression long-term at specific mean pressure levels. In general, the chance of progression appears to be reduced by 50% with when pressure levels of ⩾24 mmHg are decreased to 21–23 mmHg and another 50% to 18–20 mmHg.

It remains unclear to the authors, however, why some patients with normalized mean pressures would still progress to glaucoma. Our data provide no clear answer. Our follow-up, however, relied on multiple single IOP measurements taken over time. This follow-up strategy may not have fully delineated the 24-h pressure characteristics in some patients. Perhaps progressed patients had worse 24-h IOP characteristics associated with large fluctuations. In contrast, non-compliance to medical therapy in some treated patients may have contributed to progression to glaucoma. In addition, some patients may have had a genetic or vascular component apart from IOP that contributed to their disease.

The higher incidence of progression in patients with thin (489–514 μm) corneas by a multivariant regression analysis was not a surprise based on the results from the OHTS trial.1 The reason for this finding is not known. It has been suggested that patients with thin corneas may have weaker collagen, which might cause the optic nerve head to have a greater susceptibility to glaucomatous damage.16 Alternatively, the Goldmann tonometer may have underestimated the pressure in these patients because of the greater ease with which this instrument could applanate a thin cornea.17 More research is needed to discern the basis for higher progression rates associated with thin corneas.

The multivariant regression analysis showed other numerous statistically significant risk factors for progression. Consistent with previous studies in exfoliation or primary open-angle glaucoma, our patients with higher peak IOPs were also more likely to progress.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Also, older age has been noted previously.1 Furthermore, several findings probably were related to the study design or the nature of glaucoma as a disease and its treatment, including that progressed patients were more often untreated prior to the study and required argon laser trabeculoplasty probably to control their disease.

Of interest, however, was that patients taking β-blockers prior to the study were less likely to progress. The percentage of progression among patients taking β-blockers prior to the study was 8.9% compared to 12.5% among patients taking prostaglandins. This finding was a surprise because latanoprost is known to be a more effective ocular hypotensive agent.18 Still, β-blockers may demonstrate a systemic vascular effect. However, whether any systemic physiologic changes associated with β-blockers would positively, or adversely, impact the clinical course of an ocular hypertensive patient currently remains unknown. Future research will hopefully clarify this finding. In contrast, β-blocker use during the follow-up period was not associated with less progression.

In summary, this study suggests that pressure reduction, close to or within the normal range, reduces the chance of progression to primary open-angle glaucoma over 5 years of follow-up in patients with OHT.

This study did not evaluate patients in a prospective manner, nor were patients randomized in a masked manner to individual medicines or therapies. In addition, this study was an initial evaluation only of target pressures in OHT. Future studies should include more patients to evaluate and define potential target pressures for this disease. Hopefully, future studies will determine treatment goals and options to better safeguard long-term vision in these patients.

References

Brandt JD, Beiser JA, Kass MA, Gordon MO . Central corneal thickness in the ocular hypertension treatment study (OHTS). Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 1779–1788.

Book SA . Essentials of Statistics. McGraw-Hill Book Company:New York, 1978; 122: 205.

Stewart WC, Chorak RP, Hunt HH, Sethuraman G . Factors associated with visual loss in patients with advanced glaucomatous changes in the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol 1993; 116: 176–181.

Stewart WC, Kolker AE, Sharpe ED, Day DG, Holmes KT, Leech JN et al. Factors associated with long-term progression or stability in primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 130: 274–279.

Konstas AGP, Hollo G, Astakhov YS, Teus MA, Akopov EL, Jenkins JN et al. Factors associated with long-term progression or stability in exfoliation glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122: 29–33.

The AGIS Investigators. The advanced glaucoma intervention study (AGIS):7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 130: 429–440.

Quigley HA, Maumenee AE . Long-term follow-up of treated open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1979; 87: 519–525.

Kolker AE . Visual prognosis in advanced glaucoma: a comparison of medical and surgical therapy for retention of vision in 101 eyes with advanced glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1977; 75: 539.

Odberg T . Visual field prognosis in advanced glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol 1987; 65: 27–29.

Schulzer M, Mikelberg FS, Drance SM . Some observations on the relation between intraocular pressure reduction and the progression of glaucomatous visual loss. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 486–488.

Grant WM, Burke JF . Why do some people go blind from glaucoma? Ophthalmology 1982; 89: 991–998.

Stewart WC, Sine CS, Lo Presto C . Surgical vs medical management of chronic open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1996; 122: 767–774.

Mao LK, Stewart WC, Shields MB . Correlation between intraocular pressure control and progressive glaucomatous damage in primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1991; 111: 51–55.

Herndon LW, Weizer JS, Stinnett SS . Central corneal thickness as a risk factor for advanced glaucoma damage. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122: 17–21.

Medeiros FA, Sample PA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Aihara M, Weinreb RN . Corneal thickness as a risk factor for visual field loss in patients with preperimetric glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136: 805–813.

Stewart WC, Day DG, Jenkins JN, Passmore CL, Stewart JA . Mean intraocular pressure and progression based on corneal thickness in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2006; 22: 26–33.

Stewart WC, Jenkins JN, Stewart JA . Changes of intraocular pressure measurements and central corneal thickness following refractive surgery. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 1637.

Hedman K, Watson PG, Alm A . The effect of latanoprost on intraocular pressure during 2 years of treatment. Surv Ophthalmol 2002; 47(Suppl 1): S65–S76.

Acknowledgements

This study was not supported by any public or private funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konstas, A., Irkec, M., Teus, M. et al. Mean intraocular pressure and progression based on corneal thickness in patients with ocular hypertension. Eye 23, 73–78 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702995

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702995

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Aqueous humor cytokine levels are associated with the severity of visual field defects in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma

BMC Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Thinner retinal nerve fibre layer in healthy myopic eyes with thinner central corneal thickness

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2020)

-

Short-term reproducibility of intraocular pressure and ocular perfusion pressure measurements in Chinese volunteers and glaucoma patients

BMC Ophthalmology (2016)