Abstract

Aim

To evaluate those cases that are suitable for operation by the junior ophthalmic trainee.

Methods

A prospective survey of 96 consecutive cases from five consultant lists for phacoemulsification over a 1 month period were preoperatively assessed for their suitability for the ophthalmic trainee using set criteria. A checklist was designed for all patients and criteria were marked with reference to suitability by a single examiner. The criteria chosen were arbitrary and had no bearing on a consultant’s final decision to allow the junior to operate.

Results

Twenty-two out of 96 cases (22.9%) were deemed to be suitable for operation by a junior ophthalmologist (ie 4.4 cases per consultant list). The three main reasons for exclusion were first eye case, eye for operation with visual acuity 6/12 or better, and mature cataract.

Discussion

Using our results, if 4.4 cases were suitable for a junior ophthalmologist per month, this would allow for adequate exposure during the early stages of training. However, if the number of relatively straightforward cases on training lists were to be reduced owing to unavailability on hospital waiting lists, this could potentially compromise ophthalmic training in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The junior ophthalmic trainee is faced with the daunting task of picking up new skills quite rapidly. Phacoemulsification surgery is the commonest intraocular procedure encountered and apart from occasional courses, learning is very much hands-on. There are numerous reports of surgical training in cataract surgery and visual outcomes for junior surgeons, which conclude that various factors influence the suitability of a patient for operation by a trainee.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Our study aims to determine the proportion of suitable cases in our unit over a fixed period, to assess whether the trainee has adequate exposure to cataract surgery. This is particularly relevant with the advent of Independent Sector Treatment Centres (IS-TCs) and external contracts, which could have an impact on the availability of relatively straightforward cases and therefore on future training itself.

Method

Ninety-six consecutive cases (42 men, 54 women) from five consultant lists were assessed preoperatively over a 1-month period. The mean age was 75.11 (range 34–96 years). A checklist was designed for all patients. If any of the criteria were marked, then the surgical case was deemed to be unsuitable for the Senior House Officer (SHO). The checklist used the format as shown in Table 1. Criteria marked as ‘other’ were due to patients found to have associated pathology, including (1) small eye, (2) Salzmann's nodular degeneration, (3) Parkinson's disease, (4) ankylosing spondilitis, (5) previous MRSA from nose swab, and (6) severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Results

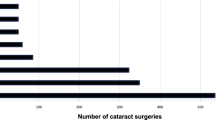

According to our criteria, 22 of the 96 cases (22.9%) were deemed to be suitable for the SHO. A consultant operated on unsuitable cases and all were uneventful procedures. The results are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

During the period of Basic Surgical Training, the SHO is required to have performed 50 cases of phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implant by the end of the second year. Our study assessed five consultant lists, each list having its own SHO. From our results, 22 cases would be suitable for five SHOs over the period of 1 month, that is, 4.4 cases per SHO per month. Potentially, this would allow for adequate exposure to achieve the target by the end of the second year. If first eye cases were deemed suitable, the number of available cases would rise considerably to 63 (65.6%).

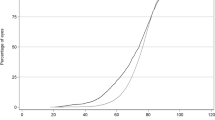

Our results have shown that the commonest reasons for exclusion are first eye case (32.8%), eye for operation with visual acuity 6/12 or better (13.6%), and mature cataract (8.8%). The broad criteria used in our study are arbitrary; in reality, these differ depending on the trainee's skill level and experience and on the decision of the senior surgeon observing the trainee. A system for preassessing cataract patients according to the risk of intraoperative complications has been suggested by one group.4 With regards to intraoperative complications, studies have shown that their frequency decreases exponentially with experience; vitreous loss rates have been shown to range from 2.6 to 5.8% for junior surgeons, with 77–90.6% of all operated patients achieving a final visual acuity of 6/12 or better.2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10 O’Brien et al11 showed that risk of endothelial cell loss was higher for trainees, concluding that less dense cataracts should be chosen for operation, thereby minimising this risk.11 There are no data to suggest that the endophthalmitis rate is any higher in procedures performed by junior surgeons.

During our study, no patients specifically requested for a consultant to operate (see Table 1). Whether or not this was due to assumption or due to unawareness of training requirements on the patient's part was not assessed. A recent study reported that patients were unhappy, regardless of surgical outcome, if they did not recall an explicit discussion about training at the time of consent.12

In England and Wales, approximately 2.4 million people aged 65 years and older are estimated to have visually impairing cataract in one or both eyes. The number of cataract procedures has increased from 153 000 in 1997–1998 to 270 000 in 2002–2003.13 In January 2005, the Department of Health announced that over 130 000 cataract patients had received treatment in IS-TCs, with mobile cataract units performing 37 cataract operations per day, 6 days a week.14 Assuming that relatively straightforward cases are removed from general ophthalmic units and placed in IS-TCs, this could further compromise the number of cases available for the trainee. A prospective study over an extended period is therefore required to investigate the impact of external contracts on surgical training. In the USA, it is acknowledged that reducing surgical numbers and funding are threatening the quality of phacoemulsification training. Prospective solutions to avoid this problem include improved wetlab training, virtual and alternative live surgical practice, and additional sources of funding for training.15 These same ideas may need to be implemented to prevent the otherwise impending decline of cataract surgery training in the UK.

References

Gibson A, Boulton M, Watson M, Fielder A . Surgical training in ophthalmology. Lancet 2002; 360 (9346): 1702.

Randleman JB, Srivastava SK, Aaron MM . Phacoemulsification with topical anesthesia performed by resident surgeons. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004; 30 (1): 149–154.

Hennig A, Schroeder B, Kumar J . Learning phacoemulsification. Results of different teaching methods. Indian J Ophthalmol 2004; 52 (3): 233–234.

Muhtaseb M, Kalhoro A, Ionides A . A system for preoperative stratification of cataract patients according to risk of intraoperative complications: a prospective analysis of 1441 cases. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88 (10): 1242–1246.

Tarbetu KJ, Mamalis N, Theurer J, Jones BD, Olson RJ . Complications and results of phacoemulsification performed by residents. J Cataract Refract Surg 1995; 21 (6): 661–665.

Tabandeh H, Smeets B, Teimory M, Seward H . Learning phacoemulsification: the surgeon-in-training. Eye 1994; 8 (Part 4): 475–477.

Prasad S . Phacoemulsification learning curve: experience of two junior trainee ophthalmologists. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998; 24 (1): 73–77.

Quillen DA, Phipps SJ . Visual outcomes and incidence of vitreous loss for residents performing phacoemulsification without prior planned extracapsular cataract extraction experience. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135 (5): 732–733.

Blomquist PH, Rugwani RM . Visual outcomes after vitreous loss during cataract surgery performed by residents. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002; 28 (5): 847–852.

Corey RP, Olson RJ . Surgical outcomes of cataract extractions performed by residents using phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998; 24 (1): 66–72.

O’Brien PD, Fitzpatrick P, Kilmartin DJ, Beatty S . Risk factors for endothelial cell loss after phacoemulsification surgery by a junior resident. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004; 30 (4): 839–843.

Vallance JH, Ahmed M, Dhillon B . Cataract surgery and consent; recall, anxiety, and attitude toward trainee surgeons preoperatively and postoperatively. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004; 30 (7): 1479–1485.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Cataract Surgery Guidelines 2004.

Department of Health. Press releases notices. Over 120000 treated since start of pioneering treatment centre programme. (Published: Friday 7 January 2005).http://www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/PressReleases/PressReleasesNotices/fs/en?CONTENT_ID=4100522&chk=KonN62.

Smith JH . Teaching phacoemulsification in US ophthalmology residencies: can the quality be maintained? Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2005; 16 (1): 27–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work has not been previously presented at a meeting

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aslam, S., Elliott, A. Cataract surgery for junior ophthalmologists: are there enough cases?. Eye 21, 799–801 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702337

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702337