Abstract

Background

The lack of prospective data comparing early surgery and medical management in primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) in the developing world led us to conduct a small randomised controlled clinical trial to evaluate acceptance and effectiveness of early trabeculectomy in these patients.

Methods

A total of 60 patients with moderately advanced POAG were randomised into three groups (Group I—Conventional medical management, Group II—Option for early trabeculectomy, Group III—Received an educational package about their disease before an option for early trabeculectomy). The patients were followed up for a period of 6 months for visual acuity, intraocular pressures (IOP), and subjective satisfaction.

Results

The three study groups were statistically similar with respect to mean IOP, demographic, and socio-economic profile. 35% of the patients accepted early surgery when offered a choice between early surgery and medical management in one of the groups. 65% of patients in another group expressed willingness for an early surgery after receiving health education on glaucoma. The mean IOP in the operated eyes was lower than the medically treated eyes at 2 weeks (16.6 vs23.0 mmHg), 6 months (18.5 vs22.8 mmHg), and 1-year review (17.9 vs22.3 mmHg) (P<0.001). No significant difference was seen among the groups with regard to visual acuity and subjective satisfaction.

Conclusion

There is a reasonable acceptance of early surgery in POAG patients in the developing world and increases on educating patients about their disease. Early surgery offers better IOP control with no long-term subjective adverse effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is a significant cause of ocular morbidity worldwide.1 The relentless progression of the disease and asymptomatic nature has challenged the blindness prevention efforts by posing greater difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. Conventional medical management is traditionally accepted as the first line of management in newly diagnosed patients of POAG. This approach seems reasonable, taking into consideration the various complications of a surgical procedure and the availability of newer antiglaucoma medications in recent years.2, 3

In the developing world, this approach may be confounded by the socio-economic dimensions. The lifelong treatment with glaucoma drops could be economically burdening to the patient.4, 5 An early surgical approach may appear as an attractive solution to this problem in the developing world. However, open-angle glaucoma causes no symptoms in the early stages to justify a surgery from the patient's point of view. The varied social, cultural, and religious beliefs have a great impact on the acceptance of any treatment by the patients.

Although there are many retrospective studies on the outcome of trabeculectomies from the developing world, there is a paucity of data comparing early surgery and medical management in POAG 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 (Table 1). The lack of large comparative studies makes it difficult to draw any definite conclusions. However, small systematically conducted studies, within the constraints of local resources, may provide data for meta-analysis in future. We conducted a randomised controlled clinical trial in our ophthalmic centre to evaluate the acceptance and outcome of early trabeculectomy POAG patients in the developing world.

Methods

In a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial, 60 recently diagnosed patients of POAG were consecutively enrolled for the study from the glaucoma services of our centre between August 2000 and September 2001. The patients included in the study met the following criteria: intraocular pressure (IOP) greater than 22 mmHg, optic disc showing glaucomatous changes, moderately advanced visual field defects (Humphrey visual field analyser, Model 745, Humphrey Instruments; Full threshold program 30–2), less than 3 months of topical antiglaucoma medications, presence of a clear media, and no systemic or local contraindications to antiglaucoma medications or surgery. The optic disc was referred to as glaucomatous when the cup/disc ratio was greater than 0.5 and/or presence of any pattern of loss of neuroretinal rim consistent with visual field loss. The moderately advanced visual field loss was defined as (1) mean deviation between –6 and –12 dB, (2) fewer than 37 points depressed below the 5% probability level and fewer than 20 points depressed below the 1% probability level, (3) no absolute deficit in the five central degrees, and (4) only one hemifield with sensitivity of less than 15 dB in the five central degrees.15 The patients were randomly assigned to three groups of 20 patients each using a computer-generated table of random numbers. A written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. A detailed demographic profile of each patient was noted.

The first group of 20 patients (Group I) were put on conventional medical management as the first line of therapy. Any patient uncontrolled on maximal tolerable medical management was eligible for surgery. The second group of 20 patients (Group II) were given a choice of early surgery and conventional medical management in the outpatient setting. The third group of 20 patients (Group III) were given an educational package by a paramedical worker. In a standardised and pretested counselling session of 20 min, involving slide-show and flipcharts, the paramedical worker explained the disease process to the patients and discussed the benefits and potential complications of either treatment modalities with these patients. This subgroup was also given a choice between early surgery and conventional medical management.

When commencing medical therapy, patients were initially prescribed a topical β-blocker. If β-blocker was inadequate or ineffective, the choice of additional drops was limited to cholinergic and nonselective or alpha-2 selective adrenergic agonists in the majority of patients. The mean interval between offer of early surgical option to patients in Groups II and III and trabeculectomy was 5.8 weeks (range 2–12 weeks). A standard phakic trabeculectomy without use of antimetabolites was performed in all cases. A triangular superficial scleral flap was dissected and a 2 × 2 mm corneoscleral tissue was excised employing a limbus-based conjunctival flap. A peripheral iridectomy was done and the superficial scleral flap was closed with two or three 10–0 nylon sutures. The conjunctiva was closed with 8–0 vicryl continuous sutures. Postoperative treatment consisted of a topical antibiotic–steroid combination, which was tapered off over 8 weeks.

All the three groups were followed up and data from visits on day 14 and 6 months was used to analyse the results. On each visit, a detailed ocular examination was carried out and the patients were asked about subjective satisfaction with their treatment modality and, where relevant, compliance to medications. Automated visual fields were obtained at 3rd- and 6th-month review. A 1-year (range 9–15 months) outcome was retrospectively analysed for operated and medically treated patients who continued follow-up in the glaucoma clinic, in an attempt to overcome the limitation of short follow-up in the study.

The patients refusing early surgery in Groups II and III were considered dropouts and were questioned regarding their reasons for the refusal. The dropouts in Groups II and III were put on conventional medical therapy and followed up during the period of study. Patients were taken as ‘lost to follow-up’ when they did not establish contact, as prearranged on entry into study, for a period of 8 weeks after failing to keep appointment.

Statistical analysis was performed by the use of commercial statistical program (Stata, College Station, TX). Frequencies of categorical variables were tabulated and compared across categories with the χ2 or Fisher's exact test. Student's t-tests and ANOVA were used to compare the age, mean IOP, and mean number of glaucoma drops between groups. Linear regression analysis of baseline IOP and IOP reduction was undertaken for operated eyes.

Results

The study comprised of 39 males and 21 females with a mean age of 58.29±12.99 years. All patients in the study were of Asian Indian ethnic origin. Table 2 shows the demographic and social profile of the patients in the three study groups. When given an option, acceptance for early surgery was observed in 35% (n=7) of patients in Group II and 65% (n=13) of patients in Group III (χ2=2.5; P=0.08). Table 3 summarises the reasons for refusal of early surgery, profile and outcome of dropouts in Groups II and III.

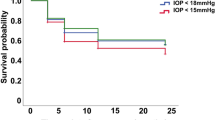

In total (Group II+Group III), 20 patients opted for early surgery and trabeculectomy was done in 22 eyes (both eyes met the inclusion criteria in two patients). Similarly in Group I, 29 eyes of 20 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included for analysis. The three study groups were statistically similar in mean baseline IOP without treatment (Group I=31.2(5.6) mmHg, Group II=31.6(5.6) mmHg, Group III=30.7(5.3) mmHg, P=0.87). At 2 weeks postoperatively, the mean IOP (SD) in Groups I, II, and III was 23.0(3.4), 20.7(4.2), and 19.0(5.5) mmHg, respectively (Groups II and III include both operated patients and dropouts on medical treatment). We found a high attrition rate in our study and only 60% (12/20) of patients in Group I, 75.0% (15/20) in Group II, and 80.0% (16/20) in Group III completed the 6 months follow-up. At 6 months, the mean IOP (SD) in Groups I, II, and III was 22.8(3.0), 21.9(5.1), and 20.5(4.2) mmHg, respectively. The mean (95%CI) IOP in the operated eyes was significantly lower than the medically treated eyes in the 6-month study period, and on a 12-month visit outside the study period. Table 4 compares the mean IOP and mean number of drops among operated and medically treated patients at 2 weeks, 6 months, and 1-year follow-up. A linear regression analysis of baseline IOP and IOP reduction (calculated from last recorded IOP without use of additional glaucoma medications) in the operated eyes is presented in Figure 1.

There was no significant difference in drop of best-corrected visual acuity among the operated and the medically treated eyes at 6-month and 1-year review (χ2=0.47, P=0.79 and χ2=1.3, P=0.5, respectively). At 2-weeks follow-up, subjective satisfaction with their treatment modality was reported by 20% (4/20) operated patients and 40% (8/20) medically treated patients (χ2=1.07, P=0.3). At 6 months, 53.3% (8/15) of the operated patients and 41.7% (5/12) of medically treated patients were satisfied with their treatment modality (χ2=0.046, P=0.83). The short period of follow-up limited a reliable comparison of operated and medically treated eyes with respect to progression of visual fields and advancement of optic disc changes.

The average inpatient stay among the operated patients was 2.3±0.92 days (range 1–4 days). Postoperative hypotony and shallow anterior chamber were found in 27.3% (6/22) of operated eyes and 9.1% (2/22) of operated eyes required bleb revision. Hyphaema was observed in 13.6% (3/22) of operated eyes. 13.6% (3/22) of the operated eyes had shallow choroidal detachments in the early postoperative period. There were no cases of early or late endophthalmitis in the operated patients.

A high attrition rate found in the study led us to investigate the profile of patients noncompliant with their appointments. At 6-month visit, there was no statistically significant difference between the compliant and noncompliant patients with respect to study group (Group I-8/20, Group II-5/20, Group III-4/20), mean age, gender, employment and health insurance. 29.4% (5/17) of patients lost to follow-up responded to a letter asking them the reasons for failed appointments. Expenses incurred on travel/medications (n=4), dissatisfaction resulting from ‘lack of permanent cure’ (n=2) and desire to seek second opinion (n=1) were the reasons given for failed appointments. All responders declined offer of future clinic services.

Discussion

This small randomised controlled trial found a reasonable acceptance of early surgery in POAG patients in the developing world. A simple educational package improved patients' understanding of the disease and, further, increased acceptance of early surgery. Early trabeculectomy offered better IOP control with comparable subjective satisfaction in the short follow-up period.

There has been an ongoing debate between early surgery and medical management as the treatment modality of choice for open-angle glaucoma.10, 11, 14, 16 In recent years, there has been a shift in trend towards initial medical treatment with the introduction of improved topical pharmacotherapies for glaucoma.17 However, it may not be possible to have a universal treatment of choice for open-angle glaucoma. The treatment should be tailored according to the socio-economic and psychological profile of the patient cohort. Any treatment modality, howsoever effective, may ultimately prove worthless if not accepted by the patients.

The acceptance for early surgery has been found to be 50% in earlier literature from the developing world.18 In one of the groups in this study, one-third of the patients accepted early surgery when offered a choice between early surgery and conventional management. 65% of patients in another group expressed willingness for an early surgery after receiving health education on glaucoma and its natural history. This supports the view that the use of patient education can improve their active participation in the treatment, especially in the developing world.19 Where resources are limited, paraclinical health staff can be effectively used for this purpose.

The results show a higher drop in IOP in the operated eyes compared to eyes on conventional medical therapy till the last follow-up.11, 14 Although, newer topical pharmacotherapies for reduction in IOP address efficacy and safety issues more successfully than the older ones,20, 21, 22 the prohibitive cost limits their widespread use in the developing world. Most of our patients did not enjoy any health insurance schemes to cover the cost of drops and could not afford any of the newer pharmacotherapies (see Table 2). At each visit, patients on medical therapy were asked which drops they were taking and at what time the drops had been instilled. With each visit, both the compliance with medications and follow-up appeared to be poorer. The expenditure incurred on medications and travelling appears to be the main cause for poor compliance observed in our study.

There was no significant difference in drop in best-corrected visual acuity in operated eyes and medically treated eyes. In our study, early trabeculectomy did not appear to hasten the progression of cataracts till the last review. There was no statistically significant difference in the subjective satisfaction reported by the operated and medically treated patients. There appear to be no long-term effects of early trabeculectomy that adversely affect the patients' quality of life.

We realise the limitations of this study. The study was a small project to evaluate the feasibility of an early surgical option in the developing part of the world. The results at 6-month review were confounded by the patients lost to follow-up. However, a favourable bias was introduced once the patients enrolled in this hospital-based study. The quality of follow-up and compliance with medications in the general population may be worse than observed in the present study. The short period of follow-up limited a critical evaluation of early trabeculectomies in this ethnic population with respect to prolonged IOP control, progression of visual fields and advancement of optic disc changes. A retrospective study on 10-year outcome of trabeculectomy without antimetabolites in the same population reports an efficacy in lowering IOP and in visual field preservation.23

In conclusion, there is a reasonable acceptance of early surgery in POAG patients in the developing world and increases on educating patients about their disease. Early surgery offers better IOP control with no long-term subjective adverse effects.

References

Thylefors B, Negrel AD, Pararajasegaram R, Dadzie KY . Global data on blindness. Bull World Health Organ 1995; 73: 115–121.

Watson PG, Jakeman C, Ozturk M, Barnett MF, Barnett F, Khaw KT . The complications of Trabeculectomy (A 20-year follow-up). Eye 1990; 4: 425–438.

Cantor L . Achieving low target pressures with today's glaucoma medications. Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48 (Suppl 1): S8–S16.

Doyle JW, Smith MF, Tierney Jr JW . Glaucoma medical treatment—2002: does yearly cost now equal the year? Optom Vis Sci 2002; 79: 489–492.

Fiscella RG, Green A, Patuszynski DH, Wilensky J . Medical therapy cost considerations for glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136: 18–25.

Thomas R, Sekhar GC, Kumar RS . Glaucoma management in developing countries: medical, laser, and surgical options for glaucoma management in countries with limited resources. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004; 15: 127–131.

Verrey JD, Foster A, Wormald R, Akuamoa C . Chronic glaucoma in northern Ghana—a retrospective study of 397 patients. Eye 1990; 4: 115–120.

Schwab L, Steinkuller PG . Surgical treatment of open angle glaucoma is preferable to medical management in Africa. Soc Sci Med 1983; 17: 1723–1727.

Janz NK, Wren PA, Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE et al. CIGTS Study Group. The Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study: interim quality of life findings after initial medical or surgical treatment of glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 1954–1965.

Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE, Janz NK, Wren PA et al. Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 1943–1953.

Migdal C, Gregory W, Hitchings R . Long term functional outcomes after early surgery compared with laser and medicine in open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 1651–1659.

Ainsworth JR, Jay JL . Cost analysis of early trabeculectomy versus conventional management in primary open angle glaucoma. Eye 1991; 5: 322–328.

Jay JL, Allan D . The benefit of early trabeculectomy versus conventional management in primary open angle glaucoma relative to severity of disease. Eye 1989; 3: 528–535.

Jay JL, Murray SB . Early trabeculectomy versus conventional management in primary open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1988; 72: 881–889.

Hodapp E, Parrish II RK, Anderson DR . Clinical decisions in glaucoma. St Louis, The CV Mosby 1993; 84–126.

Sherwood MB, Migdal CS, Hitchings RA . Initial treatment of glaucoma: surgery or medications. I. Filtration Surgery. Survey of Ophthalmology 1983; 37: 293–299.

Strutton DR, Walt JG . Trends in glaucoma surgery before and after the introduction of new topical glaucoma pharmacotherapies. J Glaucoma 2004; 13: 221–226.

Quigley HA, Buhrmann RR, West SK, Isseme I, Scudder M, Oliva MS . Long term results of glaucoma surgery among participants in an east African population survey. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84: 860–864.

Rosenthal AR, Zimmerman JF, Tanner J . Educating the glaucoma patient. BJO 1983; 67: 814–817.

Walters TR, DuBiner HB, Carpenter SP, Khan B, VanDenburgh AM . 24-H IOP control with once-daily bimatoprost, timolol gel-forming solution, or latanoprost: a 1-month, randomized, comparative clinical trial. Surv Ophthalmol 2004; 49 (Suppl 1): S26–S35.

De Natale R, Draghi E, Dorigo MT . How prostaglandins have changed the medical approach to glaucoma and its costs: an observational study of 2228 patients treated with glaucoma medications. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2004; 82: 393–396.

Cantor L . Achieving low target pressures with today's glaucoma medications. Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48 (Suppl 1): S8–S16.

Sihota R, Gupta V, Agarwal HC . Long-term evaluation of trabeculectomy in primary open angle glaucoma and chronic primary angle closure glaucoma in an Asian population. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2004; 32: 23–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This material was presented as a rapid-fire paper at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress, May 2004. We hold no proprietary interests in any of the products discussed. This study was conducted as a thesis project with no research funding

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anand, A., Negi, S., Khokhar, S. et al. Role of early trabeculectomy in primary open-angle glaucoma in the developing world. Eye 21, 40–45 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702114

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702114

This article is cited by

-

Glaucoma, “the silent thief of sight”: patients’ perspectives and health seeking behaviour in Bauchi, northern Nigeria

BMC Ophthalmology (2016)

-

Primary open angle glaucoma in northern Nigeria: stage at presentation and acceptance of treatment

BMC Ophthalmology (2015)

-

Human pericardium graft in the management of bleb's complication performed in childhood: a case report

BMC Ophthalmology (2011)