Abstract

The aim of this study is to evaluate the rate of axillary recurrences in sentinel lymph node (SLN)-negative breast cancer patients after sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone without further axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Between May 1999 and February 2002, 333 consecutive patients with primary invasive breast cancer up to 4 cm and clinically negative axillae were entered into this prospective study. Sentinel lymph nodes were identified using the combined method with blue dye (Patent blue V®) and technetium 99m-labelled albumin (Nanocoll®). Sentinel lymph nodes were examined by frozen sections, standard haematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry staining. In SLN-positive patients, ALND was performed. Sentinel lymph node-negative patients had no further ALND. The SLN identification rate was 98.5% (328 out of 333). In all, 128 out of 328 (39.0%) patients had positive SLNs and complete ALND. A total of 200 out of 328 (61.0%) patients were SLN negative and had no further ALND. The mean tumour size of SLN-negative patients was 16.5 mm. The mean number of SLNs removed was 2.1 per patient. There were no local or axillary recurrences at a median follow-up of 36 months. The absence of axillary recurrences after SLNB without ALND in SLN-negative breast cancer patients supports the hypothesis that SLNB is accurate and safe while providing less surgical morbidity than ALND. Short-term results are very promising that SLNB without ALND in SLN-negative patients is an excellent procedure for axillary staging in a cohort of breast cancer patients with small tumours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) has been the surgical standard treatment of the axilla for breast cancer patients for decades and is about to be replaced by sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy (SLNB) for patients with early-stage breast cancer. The rationales for ALND are the exact staging and prognosis, the regional control in the axilla and the possibility of survival improvement (Fisher et al, 1980; Harris and Osteen, 1985; Petrek and Blackwood, 1995). The extent of the axillary lymph node involvement is one of the most important independent prognostic factors for recurrence and survival in patients with invasive breast cancer (Carter et al, 1989; Rosen et al, 1989, 1993; Rosen and Groshen, 1990; NIH Consensus Conference, 1991; Mustafa et al, 1998). However, ALND is associated with major problems such as pain, restriction of arm motion or chronic lymphedema. One of the most important advances in the surgical treatment of breast cancer is the introduction of SLNB. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is an innovative method for axillary staging in breast cancer patients. Many studies have shown that SLNB can accurately predict axillary lymph node status. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is a minimally invasive surgical technique for axillary staging and has the potential to reduce the morbidity of the surgical procedure (Petrek et al, 2001; Temple et al, 2002; Peintinger et al, 2003; Schijven et al, 2003). The overall risk of axillary lymph node metastases in invasive breast cancer is decreasing with the early detection of small tumours. The increasing frequency of routine mammograms and the awareness of women leads to the early detection of small breast carcinomas. The probability of axillary lymph node involvement in those patients is 30–40% (Lin et al, 1993; Petrek and Blackwood, 1995; Cady et al, 1996). These patients possibly could benefit from ALND. The remaining 60–70% with negative axillary lymph nodes may thus have an unnecessary ALND and suffer from minor to major short- and long-term morbidity of ALND. Many studies have shown that SLNB can identify axillary lymph node involvement in most patients (Krag et al, 1993, 1998; Giuliano et al, 1994, 1997; O'Hea et al, 1998; Nieweg et al, 2001). The aim of this study was to evaluate the rate of axillary recurrences in SLN-negative patients after SLNB alone, without further ALND.

Patients and methods

A total of 333 consecutive patients with invasive breast carcinomas was included in this prospective study between May 1999 and February 2002. Diagnosis of invasive breast carcinoma was performed by core needle biopsy prior to surgery in all cases. All patients had clinically negative axillae. Patients, who had in situ carcinomas, multicentric carcinomas or patients with locally advanced disease or tumours larger than 4 cm or clinically positive axillary lymph nodes were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. For the identification of SLNs, the combined technique using blue dye and radioactive tracer was performed. Technetium-99m-labelled albumin (Nanocoll®, Sorin Biomedica, Saluggia, Italy) was injected peritumorally 16–18 h before surgery at a dose of 30–60 MBq by the nuclear medicine physician if the tumour was palpable. The injection was performed by ultrasound guidance if the tumour was not palpable. A dynamic lymphoscintigraphy was performed after injection and before surgery. The skin overlying the hot spot was marked with a skin marker. Subareolar subcutaneous injection of 2 ml of blue dye (Patent Blue V®, Laboratoire Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) was performed in the operating room after draping of the patient, and exactly 5 min after injection of the blue dye the axillary incision near the hot spot was performed. Careful and bloodless dissection was performed to identify the blue lymphatic channels leading to the blue SLN. Additionally, a gamma probe (C-Trak, Care Wise, Morgan Hill, CA, USA) was used to identify the hot SLN. All hot and blue nodes were excised and frozen sections were made. Subsequently, breast surgery was performed as indicated. Axillary lymph node dissection was done in the same surgical procedure if SLNs could not be identified, or if SLNs were positive for metastases in frozen sections. No further ALND was performed, if SLNs were negative in frozen sections. If negative SLNs converted positive in permanent haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections or immunohistochemistry (IHC)-stained sections, a secondary ALND had to be performed. Sentinel lymph node biopsy alone, without ALND, was performed exclusively if SLNs were negative in frozen sections and in H&E-stained slides and in IHC-stained slides. The histopathologic examination of SLNs was performed according to the Austrian Pathology Society's consensus conference statement. SLNs were cut in 2–3 mm slices, from which 2–3 frozen sections were obtained. Slices were embedded in paraffin and serially cut in 250 μm levels. From each level, one H&E-stained slide and one IHC-stained slide using cytokeratin cocktail (AE1/AE3) were examined if the H&E-stained slide was negative for metastases. Adjuvant treatment of SLN-negative patients consisted of tamoxifen in most oestrogen receptor-positive postmenopausal women, and consisted of LHRH analogues combined with tamoxifen or anastrozole in premenopausal oestrogen receptor-positive patients. Oestrogen receptor-negative patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. All patients with breast-conserving surgery received radiotherapy to the whole breast after surgery, but no radiotherapy was given to the axilla. Postsurgical follow-up consisted of clinical controls every 3 months in combination with sonography of the breast and the axilla. Mammograms, X-ray and abdominal sonography were performed annually.

Results

A total of 333 patients were included in the study. The SLN could be identified in 328 out of 333 patients, calculating an identification rate of 98.5%. SLNs were positive for metastases in 128 out of 328 patients (39.0%). In all, 104 out of 128 patients (81.3%) had positive SLNs in frozen sections and underwent ALND immediately after SLNB in the same surgical procedure. In nine out of 128 patients (7.0%) SLNs were negative in frozen sections, but positive in permanent H&E staining, and in further 15 out of 128 patients (11.7%) SLNs converted positive in IHC staining. Hence, in 24 patients a secondary ALND had to be performed after receipt of the final pathological report. That means, 18.7% (24 out of 128) of all patients with positive SLNs, respectively 10.7% (24 out of 224) of all patients with primarily negative SLNs, respectively 7.3% (24 out of 328) of all patients, who had a successful SLNB, had to undergo secondary ALND. In total, 224 out of 328 patients (68.3%) were SLN negative in frozen sections, but dropped to 215 out of 328 (65.5%) after H&E staining in permanent sections, and totalled in 200 out of 328 (61.0%) SLN-negative patients after addition of IHC staining (Table 2). Consecutively, 15 out of 215 patients (7.0%) converted from negative to positive and were upstaged by the addition of IHC staining. Exclusively, the 200 patients whose SLNs were negative in frozen sections and permanent H&E-stained sections and in IHC staining had SLNB alone without further ALND. The mean number of SLNs removed was 2.1 per patient and the mean number of lymph nodes removed in ALND was 20.8 per patient. The SLN was the only positive node in 77 out of 128 patients (60.2%). The mean tumour size was 20.45 mm in SLN-positive patients and 16.5 mm in SLN-negative patients. The median follow-up period was 36 months with a maximum follow-up time of 56 months and a minimum follow-up time of 22 months. No local or axillary recurrence could be observed in the 200 patients, who underwent SLNB without ALND.

Discussion

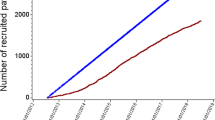

The present standard of care for treatment of early-stage invasive breast cancer is partial or total mastectomy and ALND of levels I and II, and occasionally of level III. About 30–40% of patients have positive axillary lymph nodes. The remaining 60–70% of patients are lymph node negative and may therefore be overtreated with ALND, with the disadvantage of early and late complications as seroma, pain, limited arm motion, numbness or lymph oedema of the arm and breast (Kuehn et al, 2000). Sentinel lymph node biopsy is a minimally invasive surgical procedure with significant lower morbidity than ALND (Peintinger et al, 2003; Schijven et al, 2003). The accuracy of SLNB for axillary staging has been confirmed in many studies (Krag et al, 1993; Giuliano et al, 1994, 1997; Krag et al, 1998; O'Hea et al, 1998; Nieweg et al, 2001). The long-term outcome of SLNB without ALND has not yet been evaluated and prospective randomised trials comparing SLNB alone vs SLNB plus ALND in SLN-negative patients as the American NSABP-B 32 trial or the European ALMANAC trial are in the recruitment phase. Few data exist on the local control of SLNB and there are only a few reports on SLNB alone without further ALND to date (Giuliano et al, 2000; Roumen et al, 2001; Schrenk et al, 2001; Chung et al, 2002). Axillary recurrences, as reported in those studies, range between 0 and 1.4% and follow-up periods range between 22 and 39 months. A recent study (Chung et al, 2002) reported on 208 patients with SLNB alone with a median follow-up of 26 months. In this study, three patients developed axillary recurrences after a negative SLNB, estimating a false-negative rate of 1.4%. In this study, 60% of patients received adjuvant systemic therapy. As nearly all of our patients received adjuvant sytemic treatment and all patients with breast-conserving surgery received radiotherapy to the whole breast, but not to the axilla, it cannot be stated as to what extent adjuvant treatment and radiotherapy contributed to the negative axillary failure rate in our group of patients. In our study, we have a median follow-up period of 36 months and no axillary recurrence could be observed. This may be a rather short follow-up period, but in a study on outcome of axillary recurrences after ALND (Newman et al, 2000) a median time interval of 19 months for local recurrence after ALND is reported. Axillary recurrence after ALND ranges between 0 and 3% (Recht and Houlihan, 1995). We could observe no axillary recurrence in 200 patients with a median follow-up of 36 months after SLNB only. If we had missed the true SLN and if we had an unknown false-negative rate, we should have observed 2–12% of patients (Kjaergaard et al, 1985; Senofsky et al, 1991) with axillary recurrences, which were 4–24 patients. All of our patients were SLN negative in frozen sections, H&E and IHC staining. As the impact of micrometastases identified by IHC is still controversial, we carried out ALND in all patients with IHC-positive SLNs according to our protocol. IHC was positive for micrometastases in 15 out of the 328 patients, but we could not find any further metastases in non-SLNs. A study from the Lee Moffitt Cancer Center (Jakub et al, 2002) suggested that ALND should be performed in patients with SLNs positive by CK-IHC only to reduce the false-negative rate. To date, there is no definite answer as to how to treat patients with micrometastases in SLNs. ACOSOG Z0010 will answer the question of micrometastases in SLNs and bone marrow in the near future.

The results of our study confirm the accuracy of SLNB and SLN-negative patients with SLNB alone are not at risk for axillary recurrences in a short-term follow-up. However, as long as prospective randomised studies are not available, ALND should not be abandoned as the standard of care for SLN-negative patients.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Cady B, Stone MD, Schuler JG, Thakur R, Wanner MA, Lavin PT (1996) The new era in breast cancer: invasion, size and nodal involvement dramatically decreasing as a result of mammographic screening. Arch Surg 131: 301–308

Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE (1989) Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24 740 breast cancer cases. Cancer 63: 181–187

Chung MA, Steinhoff MM, Cady B (2002) Clinical axillary recurrence in breast cancer patients after a negative sentinel node biopsy. Am J Surg 184: 310–314

Fisher B, Montague E, Redmond C, Deutsch M, Brown GR, Zauber A, Hanson WF, Wong A (1980) Findings from NSABP Protocol No. B-04 comparison of radical mastectomy with alternative treatments for primary breast cancer. I. Radiation compliance and its relation to treatment outcome. Cancer 46: 1–13

Giuliano AE, Haigh PI, Brennan MB, Hansen NM, Kelley MC, Ye W, Glass EC, Turner RR (2000) Prospective observational study of sentinel lymphadenectomy without further axillary dissection in patients with sentinel node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 13: 2553–2559

Giuliano AE, Jones RC, Brennan M, Statman R (1997) Sentinel lymphadenectomy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 15: 2345–2350

Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL (1994) Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg 220: 391–401

Harris JR, Osteen RT (1985) Patients with early breast cancer benefit from effective axillary treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat 5: 17–21

Jakub JW, Diaz NM, Ebert MD, Cantor A, Reintgen DS, Dupont EL, Shons AR, Cox CE (2002) Completion axillary lymph node dissection minimizes the likelihood of false negatives for patients with invasive breast carcinoma and cytokeratin positive only sentinel lymph nodes. Am J Surg 184: 302–306

Kjaergaard J, Blichert-Toft M, Andersen JA, Rank F, Pedersen BV (1985) Probability of false negative nodal staging in conjunction with partial axillary dissection in breast cancer. Br J Surg 72: 365–367

Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT (1993) Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol 2: 335–339

Krag DN, Weaver DL, Ashikaga T, Moffat F, Klimberg VS, Shriver C, Feldman S, Kusminsky R, Gadd M, Kuhn J, Harlow S, Beitsch P (1998) The sentinel node in breast cancer – a multicenter validation study. N Engl J Med 339: 941–946

Kuehn T, Klauss W, Darsow M, Regele S, Flock F, Maiterth C, Dahlbender R, Wendt I, Kreienberg R (2000) Long-term morbidity following axillary dissection in breast cancer patients – clinical assessment, significance for life quality and the impact of demographic, oncologic and therapeutic factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 64: 275–286

Lin PP, Allison DC, Wainstock J, Miller KD, Dooley WC, Friedman N, Baker RR (1993) Impact of axillary lymph node dissection on the therapy of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 11: 1536–1544

Mustafa IA, Cole B, Wanebo HJ, Bland KI, Chang HR (1998) Prognostic analysis of survival in small breast cancers. J Am Coll Surg 186: 562–569

Newman LA, Hunt KK, Buchholz T, Kuerer HM, Vlastos G, Mirza N, Ames FC, Ross MI, Singletary SE (2000) Presentation, management and outcome of axillary recurrence from breast cancer. Am J Surg 180: 252–256

Nieweg OE, Rutgers EJ, Jansen L, Valdes Olmos RA, Peterse JL, Hoefnagel KA, Kroon BB (2001) Is lymphatic mapping in breast cancer adequate and safe? World J Surg 25: 780–788

NIH Consensus Conference (1991) Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. J Am Med Assoc 265: 391–395

O'Hea BJ, Hill AD, El-Shirbiny AM, Yeh SD, Rosen PP, Coit DG, Borgen PI, Cody III HS (1998) Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: initial experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. J Am Coll Surg 186: 423–427

Peintinger F, Reitsamer R, Stranzl H, Ralph G (2003) Comparison of quality of life and arm complaints after axillary lymph node dissection vs sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer 89: 648–652

Petrek JA, Blackwood MM (1995) Axillary dissection: current practice and technique. Curr Probl Surg 32: 257–323

Petrek JA, Senie RT, Peters M, Rosen PP (2001) Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis. Cancer 92: 1368–1377

Recht A, Houlihan MJ (1995) Axillary lymph nodes and breast cancer: a review. Cancer 76: 1491–1512

Rosen PP, Groshen S (1990) Factors influencing survival and prognosis in early breast carcinoma (T1N0M0–T1N1M0). Assessment of 644 patients with median follow-up of 18 years. Surg Clin North Am 70: 937–962

Rosen PP, Groshen S, Kinne DW, Norton L (1993) Factors influencing prognosis in node-negative breast carcinoma: analysis of 767 T1N0M0/T2N0M0 patients with long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol 11: 2090–2100

Rosen PP, Groshen S, Saigo PE, Kinne DW, Hellman S (1989) Pathological prognostic factors in stage I (T1N0M0) and stage II (T1N1M0) breast carcinoma: a study of 644 patients with median follow-up of 18 years. J Clin Oncol 7: 1239–1251

Roumen RM, Kuijt GP, Liem IH, van Beek MW (2001) Treatment of 100 patients with sentinel node-negative breast cancer without further axillary dissection. Br J Surg 88: 1639–1643

Schijven MP, Vingerhoets AJ, Rutten HJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Roumen RM, van Bussel ME, Voogd AC (2003) Comparison of morbidity between axillary lymph node dissection and sentinel node biopsy. Eur J Surg Oncol 29: 341–350

Schrenk P, Hatzl-Griesenhofer M, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W (2001) Follow-up of sentinel node negative breast cancer patients without axillary lymph node dissection. J Surg Oncol 77: 165–170

Senofsky GM, Moffat FL, Davis K, Masri MM, Clark KC, Robinson DS, Sabates B, Ketcham AS (1991) Total axillary lymphadenectomy in the management of breast cancer. Arch Surg 126: 1336–1342

Temple LK, Baron R, Cody III HS, Fey JV, Thaler HT, Borgen PI, Heerdt AS, Montgomery LL, Petrek JA, Van Zee KJ (2002) Sensory morbidity after sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection: a prospective study of 233 women. Ann Surg Oncol 9: 654–662

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Reitsamer, R., Peintinger, F., Prokop, E. et al. 200 Sentinel lymph node biopsies without axillary lymph node dissection – no axillary recurrences after a 3-year follow-up. Br J Cancer 90, 1551–1554 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601765

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601765

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A prospective comparative study to assess the contribution of radioisotope tracer method to dye-only method in the detection of sentinel lymph node in breast cancer

BMC Surgery (2013)

-

Influencing factors for regional lymph node recurrence of breast cancer

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2008)

-

Factors predicting the sentinel and non-sentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2006)

-

Accuracy and reliability of sentinel node biopsy in patients with breast cancer. Single centre study with long term follow-up

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2006)

-

Axillary recurrences after sentinel node (SLN) biopsy without complete axillary dissection in breast cancer patients

British Journal of Cancer (2005)