Abstract

Data sources

Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Register and CENTRAL. Unpublished literature was searched on ClinicalTrials.gov, the National Research Register, and Pro-Quest Dissertation Abstracts and Thesis database. Hand searching of reference lists only.

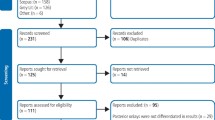

Study selection

Randomised controlled trials with a minimum of three years follow-up that compared direct to indirect inlays or onlays in posterior teeth. Primary outcome was failure (the need to replace or repair).

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently and in duplicate performed the study selection and two extracted data independently using a customised data extraction form. The unit of analysis was the restored tooth. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Meta-analysis was conducted on two studies using the random-effects model.

Results

Three studies were included. Across these studies there were 239 participants in whom 424 restorations were placed. Two studies compared direct and indirect inlays and had follow-up of five and 11 years respectively. One study compared direct and indirect onlays with a follow-up of five years. The studies were at unclear or high risk of bias. For direct and indirect inlays, Relative Risk (RR) of failure after five years was 1.54 (95% Cl: 0.42, 5.58; p = 0.52) in one study and, in another was 0.95 (95% Cl: 0.34, 2.63; p = 0.92) over 11 years. For onlays there was also no statistically-significant difference in survival, though overall five-year survival was 87% (95% CI: 81–93%).

Conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to favour the direct or indirect technique for the restoration of posterior teeth with inlays and onlays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

The adoption of a conservative and minimally invasive restorative approach, coupled with patient demands for aesthetic restorations and phasing out of amalgam means composite resin is often a material of choice when restoring posterior teeth. Direct and indirect techniques can be used and this generally well-conducted systematic review sought to help guide clinical decision-making by comparing the long-term clinical performance of direct versus indirect composite inlays and onlays in posterior teeth.

The primary outcome was restoration failure (restorations requiring replacement or repair) and secondary outcomes were secondary caries, post-operative sensitivity, marginal discoloration and colour match.

The review authors conducted an extensive literature search though they didn't report doing hand searching other than of reference lists (that is, they didn't hand search relevant journals), which could mean they didn't identify other potentially eligible studies. Studies had to have a minimum follow-up of three years and the risk of bias for each study was assessed independently and in duplicate by two authors.

Three studies met the eligibility criteria: two compared direct to indirect inlays and one compared direct to indirect onlays. The authors do not explain why they excluded 24 studies at the title-reading stage. Two of the included trials were of an unclear risk of bias and one was at high risk of bias. The included studies had follow-up periods of approximately five (two studies) and 11 years. They included 28, 157 and 54 patients with 140, 176 and 108 restorations placed respectively. Across the studies more premolars (n = 264) than molars (n = 160) were restored.

There was no statistically significant difference in the failure rates of direct and indirect composite inlay or onlay restorations in these studies. Overall, failure rates for both direct and indirect groups were two out of 100 in the five-year inlay study, 14 out of 100 in the 11-year inlay study and ten out of 100 in the five-year onlay study.

Regarding the secondary outcomes, the authors did not find a difference in the post-operative sensitivity, caries or colour matches. There was a difference in the marginal discolouration around inlays that favoured direct restorations.

Although the review seems to have been well conducted, we are aware of another, similar review published by da Veiga et al.1 a few months later in the same journal. The da Veiga review included three additional trials that compared direct to indirect composite inlays with follow-up periods of more than three years and wonder how these came to be missed or rejected. The studies were considered to be at low risk of bias (where this review had considered them to be moderate to high) and when they combined the results of these studies the risk ratio was 0.716 (95% CI 0.177 – 2.888), which though it suggests a tendency to favour direct over indirect restoration, is also statistically insignificant.

References

da Veiga AM, Cunha AC, Ferreira DM, et al. Longevity of direct and indirect resin composite restorations in permanent posterior teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2016; 54: 1–12

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dimitrios Kloukos, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, University of Bern, Freiburgstrasse 7, CH-3010 Bern, Switzerland. E-mail: dimitrios.kloukos@zmk.unibe.ch

Angeletaki F, Gkogkos A, Papazoglou E, Kloukos D. Direct versus indirect inlay/onlay composite restorations in posterior teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2016 Oct 31; 53:12–21.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dhadwal, A., Hurst, D. No difference in the long-term clinical performance of direct and indirect inlay/onlay composite restorations in posterior teeth. Evid Based Dent 18, 121–122 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401276

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401276