Abstract

Data sources

Searches for studies were made using MEDLINE, Current Contents, EMbase, CAB Abstracts and Core Biomedical Collection, and the reference lists of selected articles. A search was also made by hand of relevant journals.

Study selection

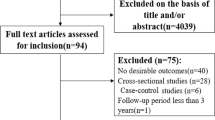

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) case–control or cohort study published as an original article; (ii) findings expressed as odds ratio or relative risk (RR) considering at least three levels of alcohol consumption; (iii) papers reported the number of cases and controls and the estimates of the odds ratios or RR for each exposure level. When the results of a study were published more than once, only the most recent and complete article was included in the analysis.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two readers, blinded to the authors' names and affiliations and to the results pertaining to alcohol consumption, independently determined the eligibility and scored the quality of the studies. Pooled estimates of the effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of each investigated condition were based on a four-step procedure. Meta-regression models were fitted considering fixed and random-effect models and linear and nonlinear effects of alcohol intake.

Results

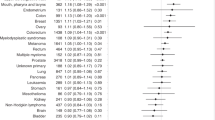

Of the 561 initially reviewed studies, 156 were selected for meta-analysis because of their quality. They included a total of 116 702 subjects. Strong trends in risk were observed for hypertension, liver cirrhosis, chronic pancreatitis, injuries, violence and for cancers of the oral cavity, oesophagus and larynx. Less strong relationships were observed with cancers of the colon, rectum, liver and breast. For all these conditions, significant increased risks were also found for ethanol intake of 25 g per day. Threshold values were observed for ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes. For coronary heart disease, a J-shaped relationship was observed with a minimum RR of 0.80 at 20 g ethanol/day, a significant protective effect up to 72 g/day, and a significant increased risk at 89 g/day. No clear relationship was observed for gastroduodenal ulcer.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows no evidence of a threshold effect for both neoplasms and several non-neoplastic diseases. A J-shaped distribution was observed only for coronary heart disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

This is a welcome and timely systematic review of the risk of alcohol consumption on a range of diseases, many pertinent to the dental practitioner and to the public health community.

Alcohol misuse is costly to society. Estimates of between 2 and 5% of a country's annual gross national product have been calculated,1 with individual UK studies estimating the costs at between 2 and 12% of total National Health Service expenditure2 — approximately £1.7 billion in England and £0.5 billion in Scotland.3, 4

The data for this review come from 156 selected studies assessing the association between alcohol consumption and the risk for 14 major alcohol-related neoplasms and non-neoplastic diseases, plus injuries. Methodological care was taken to include most published information on alcohol and disease and due consideration was taken in the analysis of accounting for the potential confounders of gender, age and smoking.

Of most relevance to dentistry were the findings in relation to oral cancer and trauma. In assessing oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer risk, 14 case–control studies and one cohort study were included. The meta-analysis found a strong direct trend of increasing risk with increased alcohol consumption for oral and pharyngeal cancer, a stronger risk than that for both oesophageal and laryngeal cancer across all levels of alcohol drinking. A similar finding comes from an assessment of the literature (one case–control study and 11 cohort studies) on injuries and violence associated with alcohol consumption, but this was not broken down to examine different sites specifically, for example, maxillofacial trauma.

In the assessment of both oropharyngeal cancer and trauma, significant increased risks were found starting from the lowest dose of alcohol considered (25 g/day, corresponding to about two drinks per day) where there was a RR of 1.9 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.8–2.0] rising to 6.5 (95% CI, 5.8–7.2) in people drinking the highest amounts (100 g/day). Thus, there was no threshold limit to the amount of alcohol associated with increased risk, that is, there was a significant risk associated with even modest amounts of alcohol consumption. In light of these findings, there is no evidence to support the perception in some quarters that low doses of alcohol are protective against oral cancer.

The nature of the design of the meta-analysis meant that it could not assess the impact on patterns of drinking behaviour, particularly binge drinking, and this needs further investigation. Although the recent emphasis on smoking cessation advice within dental practices is important, it is now time to consider similar initiatives and research to guide dental practitioners on alcohol misuse prevention.

Practice points

-

Level of alcohol-drinking should form part of the risk assessment for oral cancer on an individual basis and at the population level.

-

Advice on sensible drinking should be integral to oral cancer prevention advice in primary health care.

-

A model of prevention of oral cancer is provided by the Oral Cancer Awareness Group, University of Glasgow Dental School. [Package: Oral Cancer Prevention and Detection for the Primary Health Care Team. www.gla.ac.uk/Acad/Dental/OralCancer]5

References

Alcohol Concern. Proposals for a National Alcohol Strategy for England, London: Alcohol Concern; 1999.

Working Group of the Royal College of Physicians. Alcohol — Can the NHS Afford It? Recommendations for a Coherent Alcohol Strategy for Hospitals, London: Royal College of Surgeons; 2001.

Prime Minister's Strategy Unit. Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy for England, London: Cabinet Office; 2004.

Catalyst Health Economics Consultants. Alcohol Misuse in Scotland: Trends and Costs — Final Report, Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2001.

Macpherson LMD, Binnie VI, Gibson J, Conway DI . Prevention and Detection of Oral Cancer. Second Edition, Edinburgh: University of Glasgow/NHS Scotland; 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: C La Vecchia, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche“Mario Negri”, Via Eritrea 62, 20157 Milan, Italy. Fax: +39 02 33200231; E-mail: lavecchia@marionegri.it

Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 2004, 38:613–619

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conway, D. Alcohol consumption and the risk for disease. Evid Based Dent 6, 76–77 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400336

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400336