Key Points

-

Describes some of the difficulties encountered in obtaining valid consent for treatment.

-

Helps to clarify the terms used such as 'capacity' and 'competence'.

Abstract

Obtaining informed consent for dental and medical treatment is a fundamental ethical and legal responsibility for all clinicians. It is an opportunity for patients to have healthcare that is based on their informed choice. The assessment of a patient's competence is an essential part of the consent process and clinicians need to be aware that patients can be misunderstood and wrongly deemed incompetent. This paper aims to aid the clinician to better understand the concept of patient competency and capacity in relation to obtaining valid consent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well recognised in Common Law that a patient has the right to autonomy. Judge Cardozo acknowledged this right in relation to surgery over 80 years ago. He stated that: 'Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without the patient's consent commits an assault'.1

Obtaining informed consent for dental and medical treatment is a fundamental ethical and legal responsibility for all clinicians as part of the 'Charter of Medical Professionalism'.2

There have been many attempts to define and describe the processes involved in obtaining valid consent. In 2001, the Department of Health stated that for adult patients, for consent to be valid it must be given voluntarily by an appropriately informed person, who has the capacity to consent to the intervention in question. In addition, acquiescence where the person does not know what intervention entails is not consent.3

There has been much debate of the meaning of the terms 'competence' and 'capacity' in the scientific literature and the law and how they can be reliably verified.4 An understanding of these terms is therefore of great importance when determining whether consent for treatment is valid.

There are additional complications due to current legal differences between Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom. It is hoped that the introduction of the Mental Incapacity Bill will clarify the rather confusing law particularly for carers and others who have to take decisions for someone who lacks mental capacity.5

Factors relating to obtaining valid consent

There are a number of factors that need to be considered during the process of obtaining consent for treatment.

Information

Patients need to be provided with adequate information about the clinical procedure including its intent, nature, sequelae, probability of success and all possible alternatives. Any information supplied to the patient about their treatment should be simple and clear. It is the responsibility of the dentist to ensure that the information provided to the patient is easily understood. It is important to avoid confusing medical terms, abbreviations or acronyms when conveying information to patients.

Choice

Consent must be given voluntarily without any form of duress or undue influence from dentist, family or carers. Consent for treatment should be considered as an ongoing process and not a one-off event.6 It is important to remember that patients are entitled to change their minds and withdraw consent at any time. If complicated treatment is planned, it is often advisable to discuss the treatment and then allow an appropriate time period to elapse, for the patient to consider the proposals being made, before readdressing the issues. Pressures such as administrative convenience, resource limitation and time constraints should not compromise the consent process. It is important that patients are not coerced into having a particular treatment just to satisfy their carers, family or clinicians.

Competence and capacity

Competence is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as: 'Sufficiency for means of living, legal capacity, right to make cognisance: attend to, not allow to go unobserved'.7 The dentist has to provide the patient with information regarding any treatment choices and also to determine whether the patient is competent to interpret the information given. It is the issue of competence and capacity that is often overlooked in the process of obtaining valid consent.

The dentist is required to determine whether the patient has the 'capacity' to interpret and appreciate the information that is being conveyed. Legally, competence does not require actual understanding but rather capacity to understand. Patients may be considered competent to make decisions about their dental health even if they are not considered competent to make decisions about other issues.5 Patients need to have sufficient ability to understand the nature of treatment, consequences of accepting or refusing treatments and both the likely benefits and risks of each given option.8,9

The ability to assess a patient's capacity to make competent decisions concerning their own care is an important skill. This assumes even greater importance for clinicians treating the elderly, chronically ill and other vulnerable groups living either on their own in the community or in residential care.10

A patient must be able to comprehend and retain information that is pertinent to the decision, including its likely consequences. People have varying levels of capacity and an individual's capacity may fluctuate over time.11 A patient's capacity to understand may be temporarily or permanently affected by a number of factors. Examples of conditions that could temporarily affect capacity include: confusion, panic, shock, fatigue, pain, medication, drugs or alcohol.12 However, even if any of these factors are present, it does not automatically render the patient incapable of giving consent. The Law Commission Report 231 published 1 March 1995 defines lack of capacity to mean if at the time of decision the person is unable to, by reason of mental disability, make a decision (understand, retain information or foresee consequences of that decision or failure to make a decision) and is unable to communicate that decision.13

Any decision made on behalf of a patient without mental capacity should be in their best interests. The factors taken into account in making that decision include: a record of any ascertainable past wishes or feelings of that patient concerning their health; the need to try and encourage the person to contribute to the decision; active involvement of any person named as someone to be consulted; involvement of spouse, relative, friend or carer interested in the patient's welfare; the donee of a continuing power of attorney; any manager appointed by a court.

Consideration may be required to determine whether referral to a specialist physician is required or simply a delay for the patient to reassess the situation.

Competent patients must be able to:

-

Demonstrate the capacity to understand the information (requiring cognitive and imaginative skills and appreciating a basic concept of the dental condition and its treatment options).

-

Make a judgement about the information in accordance with their values (requiring awareness and stability of personal life goals and values and the ability to deliberate between alternative treatment options).

-

Communicate that decision.8

Adults are always assumed to be competent unless demonstrated otherwise. If you have doubts about their competence, you should ask the question 'can this patient understand and weigh up the information needed to make this decision?'6 It is important to be aware that patients can be competent to make some health care decisions, even if they are not competent to make others.

Patients with a chronic deteriorating illness, who realise their future mental abilities or physical ability to communicate is likely to be compromised, should be encouraged to plan ahead. Although it is difficult to plan for all eventualities, it is important that someone is aware of the patient's desires in relation to issues such as future health and care requirements. The appointment of someone with continuing power of attorney to take decisions about personal welfare and health should be encouraged.

Varying standards in competence requirements

The standards for determining competence will vary according to the benefits and risks that the proposed treatment offers. Treatment that has a high risk to health or treatment that has a low risk/benefit ratio requires higher levels of competency, especially if patients are refusing treatment. The law states that 'the graver the consequence of the decision, the commensurably greater the level of competence that is required to make that decision'.14 The court of appeal (in a case concerning caesarean section) stated that a patient will lack the capacity to make a decision when:

-

The patient is unable to comprehend and retain the information that is material to the decision

-

The patient is unable to use the information and weigh it in the balance as part of the process of arriving at a decision.15,16

Refusal of treatment

Competent adults are entitled to consent to refuse treatment or to choose an alternative treatment even when it would clearly benefit their health (including life-saving treatment). The only exception to this rule is governed by the Mental Health Act 1983.4 Determining a patient's competence in the first instance however would identify whether this was a valid 'refusal'.14

The only circumstance when consent can be given on behalf of an adult patient is when the patient concerned has appointed someone to make decisions on their behalf or when the courts have appointed such a person and there is a call for proxy consent.1

In Scotland, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act of 2003 has specified the procedures to be adopted for medical treatment for patients incapable of consenting to treatment. A suitably qualified and trained medical practitioner is appointed and has specific requirements to follow in respect of the patient's treatment. The Act includes legislation for treatment of: adults, children, emergencies, treatment given over a period of time and whether the patient has the capability to give consent and accept or resist or objects to the planned treatment.

A patient with a capacity to consent can decline a treatment even if in a dentist's opinion it would be in their 'best' interest. The level of competence required to refuse treatment may be considered to be higher than that required if the patient accepts treatment. The reason for this is that in refusing treatment, the patient may be acting against the advice of the dentist who knows more about the treatment of dental disease than the patient. In this circumstance, the patient would be rejecting that advice from a position of limited understanding. The wrong decision may be regretted at a later date, as later treatment options may no longer be available or even possible. The two situations of accepting or rejecting treatment cannot therefore be regarded on a par.1

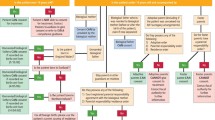

Factors which may result in the patient being erroneously classified as incompetent

The court considers that the assessment of mental incompetence should be based on the general condition of the patient rather than that at a given moment in time.14 The following examples illustrate a number of circumstances when a competent adult could be wrongly described as incompetent.

Language barriers

Difficulties in communication can occur when English is not the patient's first language. Although many trusts will provide patient information literature in several different languages, this is insufficient if the patient is unable to read or can only understand a specific dialect. It is inappropriate to judge the competence of patients whose first language is not English. In these situations, the services of an interpreter are required. The use of a child interpreter is not acceptable.12

Use of jargon and technical terms

Clinicians who may pride themselves on communication skills need to be alert to the fact that patients may not fully understand technical medical terms. Patients may feel that they have to agree to a proposed treatment, yet not fully understand the terminology.

Irregular attendees or persons with infrequent access to health care

Patients who have not accessed health care for many years may be confused by current treatment methods and further elaboration may be required. Patients may refuse treatment based on their experiences 30 years previously.

Hearing impairment

Not all hearing impaired patients will wear a hearing aid or be able to hear clearly even when wearing one. Patients who do not respond to a question can appear to be less competent simply because they may have failed to hear the question. Care must be taken to avoid speaking from behind the patient or while still wearing a facemask, which is covering your lips.

Physical impairment or mobility disability

It is important to remember that just because a patient has required help from a carer to enter your surgery, it does not mean that the carer is required to make decisions on behalf of the patient. In the case of visual impairment it is important that any advice or patient information literature is read to the patient, if it is not available in Braille. Well meaning family members or carers may unconsciously take over the decision making process, even though the patient is fully capable of making their own decision. It is important to establish that carers or relatives are not attempting to direct dental treatment for their own convenience.

Communication breakdown and behavioural problems

Communication difficulties between dentist and patient may lead to patients being wrongly judged as incompetent. It is recognised that health professionals are so accustomed to dealing with patients' families that they do not see the need to address the patient directly. Patients can easily be excluded from conversations and decisions about their treatment.

Relatives and carers of persons with learning disabilities or uncontrolled voluntary movements may avoid health services. If the patient has behavioural problems or is noisy or disruptive in the waiting room it can be all too easy to label them as lacking the capacity to understand treatment.17

Referral for tests of competence

Assessment of a patient's level of competence initially relies on the attending dentist and involves discussion with those who are closely involved with the care of the patient. Occasions may arise when a clinician finds it difficult to assess the competence of a patient. Under these circumstances it is necessary to obtain help for further assessment. The procedure for obtaining further assessment varies in different parts of the UK. At present this can include assessment from a specialist medical practitioner, psychologist, psychiatrist, specialist learning disability teams, or speech and language therapists. The involvement of these specialists forms part of the patient's overall assessment, unless the urgency of the patient's condition dictates otherwise. Where the consequences of having, or not having the treatment are potentially serious a court declaration may be required.17

Different types of tests have been devised to distinguish a patient's decision-making competence. Positive tests have attempted to assess whether a patient actually has the required abilities and qualities to make a decision about the treatment. Negative tests use a set of standard questions for assessment. However, it was found that none of the described approaches and tests offered a reliable and valid method for assessment. The tests do not take into account low scores, which may have been as a result of poor situational support, rather than genuine incompetence.18

Treatment without consent

There are limited circumstances when a dentist may proceed to provide treatment without the patient giving their consent. This is provided as non-voluntary therapy, given only when the patient is not in a position to have or to express any views as to his or her management. Examples of such cases include: when the patient is a young child and parents give consent, patients who are unconscious, or when the patient's state of mind is such as to render apparent consent invalid.

Scenarios where a court application is required for treatment without patient consent, may include:

-

1

Where there is serious dispute about a patient's capacity or their best interests

-

2

Where there is a serious unresolved disagreement between a patient's family and clinician.19

In Scotland, there are specific procedures and regulations to follow, governed by the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 2003.

Patients who are judged to lack the mental capacity to consent to a particular treatment and whose day-to-day living is dependent on the aid provided by a carer

Dentists providing treatment for this group of patients are often faced with a dilemma. In a study of the medical treatment of adults with learning difficulties, it has been reported that there is often little evidence of any routine assessment of a patient's competence to consent to treatment.20 Decision-making seemed to have been based in many cases on the assumption of incompetence, regardless of competence. Many parents and carers identified themselves as the primary decision-makers for adult patients with cognitive disabilities.17

Treatment of patients lacking competence may only proceed if the treatment is considered to be in their best interest. 'Best interests' are considered rather than best dental interests and include factors such as: the wishes and beliefs of the patient when competent (available from people close to the patient), the current wishes, the general well-being and their spiritual and religious welfare.1

Under the Mental Health Act 1983, no one can give consent on behalf of an adult lacking capacity. In Scotland, the mechanism for the provision of medical treatment, although continuing to safeguard the patient, has been addressed. In England, the Draft Mental Incapacity Bill published in 2003 is being considered following the Law Commission Report 231 on Mental Incapacity (1995). It is hoped that the introduction of a bill will protect adults who lack mental capacity, and include guidelines on healthcare. The bill will also clarify the rather confusing law particularly for carers and others who in day-to-day matters have to make decisions for someone who lacks mental capacity.

When a patient lacking competence expresses a choice, it is important to establish whether the patient is able to reconcile conflicting influences. In these situations the assistance of carers and relatives can be invaluable. The vast majority of carers and relatives involved in the care can provide information about the feelings and values of the patient. This is a great help for the dentist to help in formulating a treatment plan that is in the patient's best interests. The major determinant in deciding if a dentist has acted in the patient's best interests would be determined, as laid down in 'Bolam': whether treatment provided was a treatment which a reasonable body of professional opinion would have considered appropriate in the circumstances.21 The law considers discussion with relatives and carers as good clinical practice despite the views of these people bearing no legal status. When the prescribing dentist doubts what is in the best interests of the patient and input from relatives and carers is not conclusive in determining an outcome, other members of the healthcare team should be consulted.19 Such an approach may be regarded as wise and good clinical practice. A delay in seeking a second opinion which compromises a patient's treatment would result in the dentist being judged to have failed in their duty of care and consequently negligent.21

The fact that a patient has been assumed to be mentally incompetent and unable to make health care decisions can become the rationale for some clinicians not consulting them throughout the entire treatment. This can result in patients who find it difficult to assert their opinion in a clinical setting; thus it is important for a dentist to constantly incorporate the patient in each decision, however easy that choice may seem.17

It is hoped that the introduction of the Mental Incapacity Bill in England will provide the following: legal definition to 'capacity', introduce the criteria necessary for assessing what is in someone's 'best interest' if they lack capacity, introduce 'general authority to act', lasting powers of attorney, establish a new court to resolve complex issues and create a new office of Public Guardian. In addition to the legislation there should be a code of practice and clear guidance on decisions relating to healthcare topics such as advance refusal of medical, dental or surgical treatment, provision of emergency treatment, provision of basic care, alleviation of severe pain, and nutrition.

Conclusion

The process of obtaining a patient's consent for treatment, apart from being a necessary legal requirement, is an opportunity for patients to have healthcare that is based on their informed choice. The assessment of a patient's competence is an essential part of the consent process and clinicians need to be aware that patients can be misunderstood and wrongly deemed incompetent. Treatment may not be provided for a competent patient who withholds consent. Clinicians providing dental treatment for patients with mental incapacity will welcome the Draft Mental Incapacity Bill as it is hoped that it will clarify the legal situation for clinicians, relatives and carers.

References

Mason JK, McCall Smith RA . Consent to treatment. In Law and medical ethics. 4th ed. pp 218–237. Butterworth Heinemann, 2002.

Yeager AL . Issues in dental ethics. J Am Coll Dent 2002; 69: 53–60.

Department of Health. Reference guide to consent for examination or treatment 2001.

Welie JV, Welie SP . Patient decision making competence: outlines of a conceptual analysis. Med Health Care Philos 2001; 4: 127–138.

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on the Draft Mental Incapacity Bill. Draft Mental Incapacity Bill. Session 2002-2003. HC Paper. 189-1 HC 1803-1.

Primary Care, an edition of NHS Magazine. Feb 2002.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary. 6th ed. Austria: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Corless-Smith D . Consent to treatment. In Dental Law and Ethics. pp 63–88. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2002.

Mayberry MK, Mayberry JF . Consent with understanding: a movement towards informed decisions. Clin Med 2002; 2: 523–526.

Gallacher SM . Competency in informed consent. Ostomy Wound Manage 1999; 45: 8–9.

British Medical Association. Guidance for decision making. Withholding and withdrawing life prolonging medical treatment 2000. Part 3.

Endozien L . Policy for consent to examination or treatment 2003. Central Manchester and Manchester Children's University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Law Com No 231. Report on mental incapacity. 1995.

Bridgman AM, Wilson MA . The treatment of adult patients with a mental disability. Part 2: Assessment of competence. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 143–146.

Bridgman AM, Wilson MA . The treatment of adult patients with a mental disability. Part 3: The use of restraint. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 195–198.

Rodgers WVH . Winfield, Jolowicz on Tort Law. 16th ed. London: Sweet and Maxwell, 2002.

Adults with learning difficulties' involvement in health care decision-making. Oct 1999. http://www.jrf.org.uk/knowledge/findings/socialcare/029.asp.

Welie SP . Criteria for patient decision making incompetence: a review of and commentary on some empirical approaches. Med Health Care Philos 2001; 4: 139–151, refs 68.

The Lord Chancellor's Department Consultation Paper Making decisions: Leaflet 2 helping people who have difficulty deciding for themselves. A guide for health care professionals. http://www.lcd.gov.uk/consult.family/leaf2.htm

Checkland D, Silberfield M . Mental competence and the question of beneficent intervention. Theor Med 1996; 17: 119–134.

Bridgman AM, Wilson MA . The treatment of adult patients with mental disability. Part 1: Consent and duty. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 66–68.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Henwood, S., Wilson, M. & Edwards, I. The role of competence and capacity in relation to consent for treatment in adult patients. Br Dent J 200, 18–21 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813118

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813118

This article is cited by

-

An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

British Dental Journal (2008)

-

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its impact on dental practice

British Dental Journal (2007)