Key Points

-

Discusses the indications for using an extraoral approach when surgically removing a lower third molar.

-

Discusses the normal radiographic appearance of the ID canal and possible variations.

-

A useful reminder of anatomy in the submandibular region.

Abstract

This case report illustrates an example of when an extraoral approach was successfully used to remove a lower left third molar.

Similar content being viewed by others

Case study

A 39-year-old male was referred to the Maxillofacial Surgery Department by his general dental practitioner with pericoronitis of the lower left third molar. He gave a history of significant intermittent left sided facial swelling and bad taste. Each episode resolved after a few days with antimicrobial treatment. On examination the lower left third molar was unerupted; however, there was a deep pocket distal to the lower left second molar.

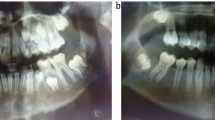

Radiographic examination (Fig. 1) showed a horizontally and deeply impacted third molar immediately related to the inferior dental nerve and the lower border of the mandible. No other features of an intimate relationship between the neurovascular bundle and third molar were seen. There was a radiolucent area associated with the crown of the tooth. This corresponded clinically to a sinus discharging pus into the mouth. All other teeth in the lower left quadrant were clinically and radiologically assessed as disease free.

As the patient was experiencing continuing symptoms, the decision was taken to remove the tooth under general anaesthetic. Via a standard transoral approach, extraction was attempted. The root of the tooth was found to be apparently ankylosed and a decision made that further bone removal would have been likely to cause morbidity to the inferior dental nerve and possible fracture of the mandible. Without consent for an extra oral approach the patient was sutured and recovered with the tooth still in situ. Although the preoperative radiograph does not classically show features of ankylosis, close inspection does not reveal any defined space between the lamina dura and the apical third of the root.

The patient was reviewed one month following surgery when he reported paraesthesia of the ipsilateral mental nerve and a foul tasting discharge into the mouth. This settled with one course of antimicrobial therapy and within four months sensation to the lip returned fully. Due to lack of further infective episodes and good healing it was decided to monitor the patient. Serial radiographs showed good bony in-fill in the area of surgery.

One year following the surgery the patient attended complaining of intermittent pain and swelling in the same area. This failed to settle with a course of antibiotics. Further imaging using a dentogram (a sectional CT scan) (Fig. 2) revealed the ID nerve had been displaced buccally and was situated immediately adjacent to the crown of the tooth. Given the continuing symptoms, this additional information, and the knowledge provided by the previous surgery, a decision to use an extraoral approach was made.

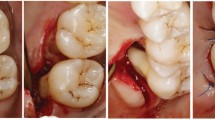

A standard submandibular approach was used and the marginal mandibular nerve identified and protected. The facial artery and vein were ligated and divided to allow greater access to the lower border of the mandible. A drill was used to remove the overlying bone on the lingual side of the lower border of the mandible. Through this lingual approach it was possible to visualise the crown of the tooth. Care was taken to ensure the tooth was disimpacted from the surrounding bone. It was sectioned before any attempt was made to elevate the tooth, so minimum pressure was exerted to the mandible, thus reducing the chance of fracture. The crown was elevated (Fig. 3) followed by the roots. Any residual fibrous tissue was debrided from the area and the inferior dental bundle was identified intact. An extra oral drain was placed to prevent a haematoma developing and to allow the blood loss from the surgical site to be monitored. The soft tissues were closed in layers.

The patient was discharged from hospital the following day and reviewed one month after surgery. At this time he had slight residual swelling. Normal function of the facial, inferior dental and lingual nerves was demonstrated. A radiograph taken six months post operatively showed good bony infill in the region of surgery.

Discussion

Before surgical removal of an impacted mandibular tooth a careful clinical and radiographic assessment should be carried out. The method of extraction depends largely on correct interpretation of a pre-operative radiological imaging.

We now work in an increasingly litigious environment making accurate assessment of the relationship of the ID canal to the apices of the tooth particularly important. The normal radiographic appearance of the ID canal is two thin parallel radiopaque lines (tramlines). Variations that indicate a possible intimate relationship include: loss of tram lines, narrowing of tram lines, a sudden change in direction of the tram lines, and a radiolucent band across the tooth root if the tooth is grooved or tunnelled through by the ID canal.

The use of an extra oral approach to remove teeth is rarely indicated.1 Table 1 shows the clinical indications given in previous publications for using an extraoral approach. This case illustrates an example where an extra oral approach can be successfully used.

References

Dhaig G . Extraoral extraction of teeth. J Irish Dental Ass 1996; 42: 18–19.

Plumpton S . The extraction of mandibular teeth via an extraoral approach. Br J Oral Surg 1966; 4: 127–131.

Christenson RO . Extraoral impaction of an impacted lower third molar: report of a case. J Oral Surg 1950; 8: 335–337.

Blake H, Blake F . Extraoral removal of an unerupted mandibular cuspid. Oral Surg Oral Path Oral Med 1954; 8: 1197–1200.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milner, N., Baker, A. Extraoral removal of a lower third molar tooth. Br Dent J 199, 345–346 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812693

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812693

This article is cited by

-

Ectopic third mandibular molar: evaluation of surgical practices and meta-analysis

Clinical Oral Investigations (2021)