Key Points

-

The education and training system for dental technicians in Scotland currently lacks resource and structure.

-

The advent of mandatory CPD following registration will be difficult for many people in Scotland to access because of geographical location.

-

The shortage of funding for CPD poses a problem for dental technicians.

-

Rates of remuneration are inadequate and unlikely to encourage people in to the profession in the future.

Abstract

Objective To investigate the educational needs and employment status of dental technicians in Scotland.

Subjects Two hundred and fifty dental technicians with postal addresses in Scotland.

Design Structured questionnaire.

Results An 83% response rate was achieved following three mailings. The majority of respondents were employed in commercial dental laboratories largely within the 'central belt' of Scotland, with 96% stating they were in full-time employment. Only 33% of these essential health-care workers were voluntarily registered with the Dental Technicians' Association, suggesting that a significant number had not felt it necessary or beneficial to do so. A lack of educational structure was identified, as was poor remuneration and an absence of opportunity for career progression. Although the prospect of continuing professional development was desirable, many respondents reported that they would be penalised financially for undertaking this and, in addition, may not be given the opportunity to pursue education because of lack of co-operation from their employer. Only 47% had attended an educational event within the preceding year, and of those who had not done this, a period of two-32 years had elapsed since any CPD involvement. Of the respondents, only 34% stated that any financial assistance had been available for educational purposes, with access to education being highlighted as problematic by 68%. A total of 64% of subjects felt they were out-of-date with professional education.

Conclusions This study highlights a number of real and potential problems in the field of education in dental technology. It is apparent that change within the structure of education and professional status, although largely welcomed, may be difficult to implement. The profession, as a whole, must realise that these changes in education and employment are not optional, and should be embraced as a positive step which will hopefully raise the profile and status of dental technicians throughout the UK.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oral health, function and appearance of patients receiving modern-day dentistry are dependent upon the clinical skills of those involved in the provision of treatment and the technical prowess of the dental technician. Dental technician education and training has changed dramatically over the last 25 years, however, many aspects of their position in terms of status and professional profile within the dental team have unfortunately remained the same.1

Historically, these professionals were known as dental mechanics and no restriction was placed on their capacity to undertake duties associated with dental technology, whether trained or not. There was also no requirement for those running dental laboratories to hold a recognised qualification.2 This situation remained unchanged until 1998 when the General Dental Council (GDC) made the decision, as part of its reform programme, to register all groups of professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs).3 This was instigated by the Nuffield Foundation Report into Education and Training of Personnel Auxiliary to Dentistry, which was a far-reaching and long-awaited document of investigation, that resulted in a number of significant changes being implemented.2

It was the intention of the Scottish Executive that by 2004, there would be an output of at least 15-20 dental technicians qualifying annually, with up to 35 student technicians in education and training.4 However, this is not now expected to be in place until 2006. Currently, education in dental technology is available in both full and part-time settings and offers the National Certificate, Higher National Certificate and Higher National Diploma. Only three cities in Scotland offer such training, these are Edinburgh, Dundee and Glasgow, in a combination of dental schools and colleges of further education. A degree in dental technology is only available in the UK within the University of Manchester, although discussion is underway in the hope of developing this programme in one of the universities in Scotland.

There is a distinct paucity of information in relation to this increasingly important group of PCDs, and the aim of this study was to determine the current situation in terms of individual educational requirements and employment status, in order to inform those responsible for future developments within the field of dental technology.

Methods and materials

There is no formal register for dental technicians in the United Kingdom although this situation will change in 2005 when mandatory registration of all groups of PCD commences. In an attempt to identify as many of these healthcare professionals in Scotland as possible, data were taken from the voluntary Dental Technicians' Association Register and, in addition to this, individual commercial laboratories, dental hospitals and NHS trusts and colleges of education were targeted, in the hope of building as robust a database as possible for future research and workforce planning purposes. Subjects were requested to complete a proforma indicating their name, address and status within their laboratory of employment, and also the name and address of their employer.

On receipt of these completed forms, a needs assessment questionnaire was formulated and distributed to 250 dental technicians in Scotland who had responded to the initial request for information. This questionnaire was derived from that which was used in a previous study, which investigated the educational needs and employment status of Scottish dental hygienists.5 Modifications were made to this questionnaire and, based on these, appropriate questions were developed for dental technicians. Following three separate mailings, a total of 207 (83%) were returned and subsequently analysed.

Results

Personal details

A total of 162 (78%) of the respondents were male; 45 (22%) were female.

Qualifications

Subjects were asked to state whether they held qualifications in dental technology and, of those who responded (189), 169 (89%) reported that they did while 20 (11%) stated that they did not. The majority held the City and Guilds of London qualification in dental technology and the range of qualifications held is shown in Figure 1.

The number in training to become a dental technician was explored, and it was revealed that of those who answered this question (n=198), only 26 (13%) were undergoing training leading to a qualification. Of the remainder (n=172), 10 (6%) subjects reported that they neither held any qualifications, nor were they in training. The remaining 162 (94%) held one or more qualifications, but were no longer undertaking further education within the field of dental technology.

Voluntary registration was assessed, and it was established that 33% of respondents (n=202) were registered with the Dental Technicians' Association.

Subjects were questioned about professional qualifications held outside dental technology and it was determined that of those who replied to this query (n=190), 32% (60) did so and 68% (130) did not. The range of qualifications held are illustrated in Table 1.

Employment information

Of the respondents to this question (n=204), 96% (195) reported being in full time employment and only 4% (9) stated that they were in part time work. The majority indicated that they were employed either in a commercial laboratory setting or by an NHS Trust. Results are illustrated in Figure 2.

Those employed within a commercial dental laboratory (n=98) were asked to state whether they were the laboratory owner or an employee. Responses to this question indicated that 47% (n=46) were owners and 53% (n=52) stated they were employees.

Subjects who were employed outside a commercial laboratory were questioned regarding the position and grade they held within their employment. A total of 112 (54%) responded and details of this are shown in Figure 3. The breakdown of 'Other' in relation to this question is detailed in Table 2.

Specialisation

Subjects were asked if they specialised in a particular area of dental technology. Results are presented in Figure 4.

Time in employment

The time in employment as a dental technician ranged from one month to 54 years. These figures are illustrated in Figure 5.

Geographical location of employment

Technicians were asked to specify their location of employment and the majority of respondents were employed within the central belt of Scotland. Results are shown in Figure 6.

Continuing professional education

Affiliation to professional organisations other than the Dental Technicians' Association was explored, and of those who responded (n=201), 47 (23%) belonged to one or more of the technicians' professional bodies. Results are shown in Figure 7.

Access to meetings and courses

Of those who responded to this question (n=196), 47% (n=93) stated that they had access to educational courses or meetings in relation to dental technology. The majority of respondents (47%) had attended one educational session during the preceding year. Those who had not attended any sessions in the previous year were asked when they last attended such an event, and this ranged from 1971-2000. Full results are shown in Figure 8.

Funding issues

Issues in relation to funding were explored, and it was found that financial assistance to attend courses or meetings had been available to only 67 (34%) of subjects who replied (n=195).

Access issues

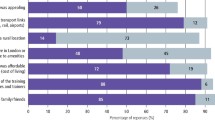

Access to CPD was reported as being difficult by 134 (68%) of those who answered this question (n=197) and, in relation to this, 130 (64%) felt that they were not up to date with their education in dental technology.

Educational subjects

Technicians were asked to suggest CPD subjects for prospective inclusion in educational programmes which they felt would be of value to them in their current employment. These are shown in Figure 9.

Other subjects suggested by individuals were digital photography, management issues, clinical dental technology, maxillofacial issues, appliances for special needs patients, business management and medical issues in dentistry.

Comments

An open section for comments was included in the questionnaire which elicited a number of interesting responses. Several comments were made, the more important of which are detailed in the following section.

Education and funding issues

-

Most courses available in London or Manchester

-

Impossible to fulfil CPD because of time-constraints and location of employment

-

Funding dependent on employing authority

-

Too expensive to attend courses in England

-

Lack of funding specifically for dental technology

-

Funded 50% of HND personally — others receive nothing

-

Difficult to access courses which do not revolve around one product

-

Employer stated that day-release course would be available, but did not materialise. Further suggestion from employer to do evening course but unable to do so as additional evening employment was necessary to supplement disgraceful wages.

-

As part-time member of staff, often overlooked in terms of CPD

-

Only had 50% of training fees paid — earning £9,590 per annum

-

Not sure if Trust will fund HNC. Course fees ∼£600 per annum. Salary £10,000 per annum. Unable to fund any further personal education

-

Poor standards of education in comparison to centres overseas

-

Funds extremely limited in employing Trust

-

Educational updates in technology usually relayed by other members of staff who have attended courses

-

No provision for evening education

-

Refused access to education by employing Trust

-

Difficult to develop education with no funding

-

Only named technicians given access to education

-

Lack of funding will lead to further shortage of technicians

-

Prioritised funding for other members of staff

-

No encouragement given for career progression from HNC to HND

-

Would like to further skills but courses are too expensive and too distant to access.

Career issues

-

No career pathway — intend to leave dental technology

-

Have been technician for 10 years and would like to further career but no opportunity available for development or advancement. Intend to leave dental technology.

-

No structure in place to promote and reward those who have attempted to master their craft. Inappropriate staff used to teach undergraduates in order to save money

-

Qualifications not recognised within Trust. Upgrading non-existent regardless of experience or qualifications

-

Career progression only available to those who are willing to move geographically.

Employment issues

-

Very poor wages with no career prospects

-

Money deducted from salary to attend courses which were self-funded in the first place

-

Long hours with poor rewards

-

No opportunity to undertake research because of lack of staffing and funding

-

Problem of working in isolation. Laboratory cannot function if one member of staff is away for any time.

Discussion

This National Educational Needs Assessment exercise has elicited a number of significant responses in relation to the education, training and employment patterns of dental technicians in Scotland. Increased sophistication in operative techniques inevitably demands superior technical skills and therefore it is vital that all involved in dental technology have skills and abilities concomitant with that dictated by dentistry today. To date, the education and training system for this group of professionals in Scotland has lacked resource and structure and is an issue which is currently being addressed by the Scottish Executive.4

The majority of technicians are employed within commercial dental laboratories and the problem of communication between dentist and technician becomes increasingly difficult as isolation increases. As part of the evolutionary process of undergraduate dental education and, more recently, revision of the curriculum as a result of the publication of the document The First Five Years by the GDC, dental students no longer devote so much time to developing practical prosthetic skills.6 Therefore, the knowledge of highly specialised technical work is firmly the responsibility of the skilled dental technician and, as such, recognition in terms of remuneration and career progression should be made available to those who elect to enter this profession.

Analysis of the data revealed that further education and funding issues posed a substantial problem for many technicians in that CPD was often dependent on the co-operation of the employer, and in certain cases access to this was frankly denied.

In some instances, it was reported that money was deducted from individuals' salaries when they attended courses, despite the fact they had been self-funded in the first place. Poor rates of remuneration were cited as being a particular source of frustration, particularly when many individuals had acquired further qualifications but had remained unrewarded financially. This is clearly a disincentive to further education and indeed, in a number of situations, the intention was to leave dental technology altogether. Skilled technicians are already scarce in Scotland, and it is of deep concern that those in whom time and effort have been invested in the past, reject the career they have chosen as a result of a lack of vision by those who determine remuneration structures, and issues relating to education and career progression.

Other employment difficulties were highlighted where it was reported that staff shortages restricted the opportunity to undertake CPD and that long hours and poor wages in some commercial laboratories, removed the possibility of further education. This is without doubt, a real concern for many technicians who, as a result of forthcoming mandatory GDC registration, will have to undertake CPD in order to remain in their profession. This, of course, is not limited to dental technicians, as there is currently no system in place for any of the PCD groups to claim expenses or compensation for loss of earnings whilst undertaking CPD.

The entire structure of education and career progression in dental technology should be addressed as a matter of urgency, in order to encourage individuals both to join and remain within the profession. This is a highly skilled group of healthcare workers who are essential for dentistry and the comfort and function of the patient. For too long, their needs have at best been sidelined, but mostly ignored. The role of the PCD is developing and dental technicians must not be forgotten. The recent publication of the new curricula for PCD gives structure to the basic education in dental technology, although degree programmes should be developed in recognition of the spectrum of work involved, and to ensure the highest quality of education for those both receiving and providing instruction in the future.7

Conclusions

This survey indicated that only 33% (n=66) of this predominantly male profession were voluntarily registered, and that 6% (n=10) were employed in a dental laboratory, but not in any training programme. Although this number is small, it indicates that the situation exists where people are in employment supposedly as dental technicians, but without formal education leading to the opportunity of achieving a recognised qualification. This number may possibly be more, as these figures only relate to those who participated in this survey. Clearly, with the forthcoming directive of mandatory registration from the GDC, these individuals will be denied the opportunity of remaining in dental technology unless their educational prospects are changed radically.

The rapid approach of statutory registration and mandatory CPD should be highlighted to all technicians, in order that their profession progresses in the manner in which it undoubtedly should, and that certain individuals are not left behind in this time of change.

References

Barrett P A, Murphy W M . Dental technician education and training – a survey. Br Dent J 1999; 186; 85–88:

Education and Training of Personnel Auxiliary to Dentistry. The Nuffield Foundation, 1993.

Professionals Complementary to Dentistry. Report of the GDC Dental Auxiliaries Review Group. March 1998.

Dentistry in the new millenium. Education and training of the Professionals Complementary to Dentistry in Scotland. Summary and Recommendations of the Working Group Report. February 2002.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Rennie J S . Educational needs and employment status of Scottish dental hygienists. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 105–109.

The First Five Years. The Undergraduate Dental Curriculum. General Dental Council, 1997.

Developing the Dental Team: Curricula Frameworks for Registrable Qualifications for Professionals Complementary to Dentistry (PCDs). General Dental Council, 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ross, M., Ibbetson, R. Educational needs and employment status of Scottish dental technicians. Br Dent J 199, 97–101 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812524

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812524

This article is cited by

-

The impact of General Dental Council registration and continuing professional development on UK dental care professionals: (2) dental technicians

British Dental Journal (2012)

-

Activity and education of clinical dental technicians: a UK survey

British Dental Journal (2007)

-

Professional development for dental technicians; a pilot study

British Dental Journal (2007)

-

Educational needs and employment status of Scottish dental nurses

British Dental Journal (2006)

-

Scottish dental technicians: needs and status

British Dental Journal (2005)