Abstract

Objective To study the therapeutic prescribing of antibiotics by general dental practitioners.

Design A postal questionnaire of National Health Service general dental practitioners in ten English Health Authorities.

Subjects General dental practitioners (1,544) contracted to provide NHS treatment in the Health Authorities of Liverpool, Wirral, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Nottingham, North Nottinghamshire, Sheffield, Newcastle, Northumberland and North Tyneside.

Main outcome measures The questionnaires were analysed and the responses to each question expressed as absolute frequencies.

Results Responses to the questionnaire were received from 929 (60.1%) practitioners. More than 95% of practitioners recognised the need for prescribing antibiotics where there was evidence of spreading infection. Some practitioners (12.5 %) prescribed antibiotics for acute pulpitis and (3.3 %) for chronic marginal gingivitis. Antibiotics were prescribed by practitioners before drainage of acute abscesses (69%) and by 23% after drainage. Practitioners were generally not influenced by patient's expectations of receiving antibiotics (92%), but would prescribe when under pressure of time (30.3%), if they were unable to make a definitive diagnosis (47.3%), or if treatment had to be delayed (72.5 %). Amoxicillin was the most frequently prescribed antibiotic used for most clinical conditions apart from pericoronitis, acute ulcerative gingivitis and dry sockets where metronidazole was the drug of choice. There was a wide variety of dosage, frequency and duration for all the antibiotics used in the treatment of acute dental infections.

Conclusions The results obtained from this questionnaire support the conclusion that the therapeutic prescribing of antibiotics in general dental practice varies widely and is suboptimal. There is a clear need for the development of prescribing guidelines and educational initiatives to encourage the rational and appropriate use of the antibiotics in National Health Service general dental practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

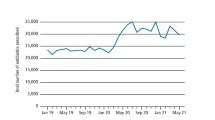

There is widespread concern about the overuse of antibiotics and the emergence of resistant bacterial strains.1,2,3 Overprescribing of antibiotics by general dental practitioners (GDPs) is not generally perceived as a problem, although in 1997 more than 3.5 million prescriptions for antibiotics were dispensed by GDPs at a net ingredient cost of £5.2 million.4 Antibiotic prescribing by dentists could therefore, play a significant part in the emergence of resistant bacterial strains, particularly if there was evidence that there was significant misuse.

There have been some limited studies of antibiotic prescribing by dental practitioners and these have shown wide variation in what is prescribed and the dosages employed.5,6,7 Only two pilot studies have investigated how practitioners prescribe and in what clinical situations.8,9 The aims of this study were to investigate when, why and what antibiotics were prescribed by a large population of National Health Service (NHS) GDPs.

The authors would like to thank all those general dental practitioners who gave so generously of their time to answer the questionnaires. The ten health authorities are thanked for providing current lists of NHS practitioners and the NHS National Primary Dental Care Research and Development Programme for providing funding for this project.

Materials and methods

Questionnaire

A questionnaire was devised to examine general dental practitioner's prescribing patterns. This questionnaire was a modification of that described by Palmer et al.9 The questionnaire was anonymous but investigated the place and year of qualification, age (banded in decades from 21 to 61 years), sex and whether any postgraduate courses had been attended on antibiotics in the previous 2 years.

The questionnaire investigated for which clinical signs the practitioner would prescribe antibiotics for patients presenting with a dental infection. The clinical signs chosen were elevated temperature, evidence of systemic spread, localised fluctuant swelling, gross diffuse swelling, restricted mouth opening, difficulty in swallowing and closure of the eye because of swelling.

Information was sought on the antibiotic dose, frequency and number of days that the practitioner would prescribe for patients with an acute dental infection, who were not allergic to penicillin. They were also asked to select their preferred choice of antibiotic for a dental infection for patients allergic to penicillin. Information was also sought on a number of non-clinical factors to determine if they affected practitioners' prescribing. Specifically, questions were asked whether or not the patient's expectation of an antibiotic prescription, pressure of time and workload, the patient's social history, uncertainty of diagnosis, or if treatment had to be delayed would cause an antibiotic to be prescribed.

Information was sought on the use of antibiotics for common clinical conditions, if a positive response was made then the practitioners were asked to state what antibiotic would be prescribed. The clinical conditions were acute pulpitis, acute periapical infection (before, with or after drainage), chronic apical infection, pericoronitis, cellulitis, periodontal abscesses, acute ulcerative gingivitis, chronic marginal gingivitis, sinusitis, chronic periodontitis, dry socket, trismus and reimplantation of teeth.

Sample and data handling

Ten health authorities were chosen for sampling, these were Liverpool, Wirral, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, North Tyneside, Northumberland, Newcastle, Nottingham, North Nottinghamshire and Sheffield. All the general dental practitioners contracted to provide NHS General Dental Services were included from the health authority lists; specialist practitioners (eg orthodontists) were excluded. Questionnaires were sent out at the beginning of February 1999 with a freepost envelope which was coded with an area code, so that the response rate from any locality could be assessed. The respondent dentists could not be identified from the completed questionnaire.

The questionnaires received were entered into a Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) database.10 From this database the overall response rate was calculated, together with the percentage responses for each question.

Results

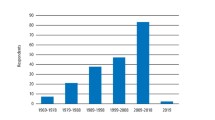

A total of 929 replies were received giving a response rate of 60.1%; 38 of the returned questionnaires were incomplete resulting in 891 useable replies. All the dental schools in the UK were represented, 71.5% males and 28.5% females responded and there was a normal distribution of age groups. Only 21.5% of the respondents had attended postgraduate courses on antibiotics in the previous 2 years.

Table 1 shows the clinical signs for which practitioners would prescribe antibiotics. Elevated temperatures, gross diffuse swelling, difficulty in swallowing and closure of the eye, were the principal clinical indications for antibiotic prescribing.

Table 2 shows the antibiotics prescribed for adults with an acute dentoalveolar infection, the frequencies, dosages and length of the course. Amoxicillin was the principal antibiotic prescribed with 70.5% choosing this antibiotic as their first choice. The principal dosage of amoxicillin was 250 mg three times daily for 5 days, but 3 g, 200 mg and 500 mg were also used, the latter two doses for periods of 3 to 10 days, and three to four times daily. Penicillin V was the next most popular first choice of antibiotic with 20.5% using it; the dosages and frequency were mainly 250 mg and four times daily for 5 days. Metronidazole was used by 7% of the respondents at dosages of 200, 250 and 400mg for 3 to 7 days. Both ampicillin and cephalexin were prescribed by only 0.5% of respondents. The main choice of therapeutic antibiotic for patients allergic to penicillin was either erythromycin 46.7%, or metronidazole 48%: the other choices were tetracycline (0.9 %) or cephalosporins (1.3%).

The non-clinical factors influencing antibiotic prescribing are shown in Table 3. Almost half the practitioners surveyed used antibiotics when they were uncertain about the diagnosis or when under pressure of time (30%). Circumstances where treatment had to be delayed accounted for 72.5% of prescribing.

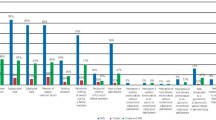

The percentage of practitioners prescribing for specific conditions is shown in Figure 1. The majority prescribed for acute periapical lesions before drainage, pericoronitis, acute ulcerative gingivitis, dry sockets, periodontal abscesses and the reimplantation of teeth. More than 10% prescribed for acute pulpitis and chronic periodontitis. The GDPs' choice of antibiotics for specific conditions, assuming no allergy to penicillin, are shown in Table 4. Amoxicillin or metronidazole were the most used antibiotics for all the conditions surveyed.

Discussion

There are about 15,800 dentists practising (excluding assistants and vocational trainees) within the NHS General Dental Services in England, 72% are male and 28% female.11 This study aimed to sample around 10% of GDPs. The geographical areas chosen for the study included rural and inner city areas and 1,544 dentists were surveyed. When the sample was analysed the 60.1% response rate had a male to female split of 71.5% male and 28.5% female; graduates representing all the English dental schools and a normal distribution of age groups. Although it was hoped to achieve a higher response rate, research in general medical practice has suggested that the primary reason for non-response to postal surveys is that questionnaires get lost in other paperwork, that practitioners are too busy or that the questionnaires are routinely binned.12

The indications for antibiotics in acute dentoalveolar infections are well defined as signs of spreading infection, patient malaise, temperature elevation and lymphadenitis.13,14 Generally this survey showed that GDPs are aware of these indications and mostly used antibiotics judiciously for acute infections (Table 1). However, more than one third would prescribe antibiotics for a localised fluctuant swelling and where there was no evidence of trismus. This study suggests therefore that a significant proportion of practitioners prescribed antibiotics for all swellings where local treatment would have sufficed.

Amoxicillin was the most frequently prescribed antibiotic for acute dentoalveolar infections requiring antibiotics, followed by phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin V). The antibiotic of choice for acute dentoalveolar infections has traditionally been phenoxymethylpenicillin and this antibiotic, at a dose of 500 mg, is currently recommended by the Dental Practitioners Formulary (DPF).15 The use of phenoxymethylpenicillin was based on old studies that had isolated mainly streptococci and staphylococci as the main bacteria from dental abscesses.6,16,17 More recent studies have shown that the main isolates from dental abscesses are complex mixtures of facultative and anaerobic bacteria, some of which are penicillin resistant.18,19 The main choices of antibiotics by the practitioners in the survey for dental abscesses were amoxicillin and metronidazole. The use of amoxicillin and metronidazole is supported by some microbiological and clinical findings,20,21,22 but the DPF still recommends phenoxymethylpenicillin as the first choice for most dentoalveolar infections.15 Erythromycin and metronidazole were used by the dentists surveyed for dental abscesses in patients allergic to penicillin, concurring with the advice in the DPF.15

The wide range of doses and duration of antibiotics prescribed for dentoalveolar infections was alarming. There is increasing evidence that short courses of antibiotics, together with local surgical measures, are adequate for the resolution of dentoalveolar infections.23 Prolonged courses of antibiotics, which were recommended by some of the practitioners in the survey, for periods up to 10 days, could be harmful by selecting resistant bacteria and abolishing colonisation resistance.24 Large doses of amoxicillin (500 mg) are not indicated in acute dentoalveolar infections as the absorption of this antibiotic in standard 250 mg amounts is good enough to be therapeutically effective.19 A minority of practitioners used the two-dose 3 g amoxicillin regime which has been shown to be effective for dental abscesses in some specific situations.21

Although most of the practitioners in the survey (90%) would not be influenced to prescribe antibiotics because of patient expectation, 30% would prescribe because of shortage of time and 47% if they were unable to make a definitive diagnosis. The decision to prescribe antibiotics must be based on a thorough medical history, clinical examination and accurate diagnosis. The use of antibiotics for the eradication of the cause of an acute dentoalveolar infection is difficult to support on clinical or medico-legal criteria. There are some clinical situations where antibiotics can be used where treatment has to be delayed eg where drainage cannot be established, 72% of practitioners used them for this purpose. However, evidence from other studies showed that antibiotics were used in 50% of out-of-hours emergency consultations in which there was evidence of infection in only 25% of cases.25

There is no indication for prescribing antibiotics for acute pulpitis,26 yet 13% of practitioners used them for this condition. Similarly, more than 3% of the survey prescribed antibiotics for chronic marginal gingivitis; antibiotics are not indicated for this purpose. There was similar confusion over the use of antibiotics in the presence of purulent infection. In this study 69% used antibiotics prior to drainage and 45% when it was established. Drainage of an infection is the only treatment necessary in the majority of uncomplicated infected swellings. Chronic apical infections rarely need antibiotics unless there is evidence of gross local spread; extraction or root canal therapy are the definitive treatment options. In this survey more than a quarter of those surveyed would prescribe antibiotics for chronic apical infections.

Pericoronitis, periodontal abscesses and dry sockets can be effectively treated by local measures and antibiotics are only indicated for large spreading infections, or systemic involvement. The majority of practitioners routinely prescribe antibiotics for these conditions. Most of those surveyed would correctly prescribe antibiotics for cellulitis, trismus and acute ulcerative gingivitis, with amoxicillin and metronidazole being the antibiotics of choice. The majority of those surveyed prescribed prophylactically for reimplanting avulsed teeth as recommended.27 The prescribing of antibiotics for sinusitis is controversial. Recent research has shown that antibiotics do not affect the clinical course of the disease.28 From this survey 54% of dentists would prescribe antibiotics for sinusitis when it is unlikely to have any effect.

The results of this survey have shown that the prescribing of antibiotics by dentists is often not based on sound clinical principles. Most of those surveyed used antibiotics routinely for conditions where local treatment would suffice. This survey supports the conclusion that there is overprescribing of antibiotics within NHS general dental practice in England. Part of the problem is that the DPF, which is designed for all grades of dental personnel within the NHS, gives only general guidelines on prescribing rather than definitive regimes. GDPs need clear, simple and practical advice on when to prescribe, what to prescribe, for how long and in what dose. The Faculty of General Dental Practitioners of the Royal College of Surgeons is shortly to publish recommended standards for antimicrobial prescribing for dental practitioners which may help to combat overprescribing.29 There is also an urgent need for consistent antimicrobial policies to be taught to dental undergraduates within schools. A small survey of antibiotic teaching within dental schools (results not shown) revealed a wide disparity in the teaching of antibiotic usage. Finally, there is a clear need for research in the efficacy and indications for antibiotic use, to provide evidence-based regimens for general dental practitioners.

References

Monitoring and Management of Bacterial Resistance to Antimicrobial Agents: a World Health Organisation Symposium. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 24 (suppl 1): S1–176.

Standing Committee of Science and Technology House of Lords. Resistance to antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents. London: The Stationary Office, 1998.

Wise R, Hart T, Cars O, Streulens M, Helmuth R, Huovinen P, et al. Antimicrobial resistance is a major threat to public health [editorial]. Br Med J 1998; 317: 609–610.

Prescription Cost Analysis System. Dental practitioner prescribing – Antimicrobials. Department of Health, Statistics Division 1E, 1998.

Thomas D W, Satterthwaite J, Absi E G, Lewis M A O, Shepherd J P . Antibiotic prescription for acute dental conditions in the primary care setting. Br Dent J 1996; 181: 401–404.

Lewis M A O, Meechan C, MacFarlane T W, Lamey P J, Kay E . Presentation and antimicrobial treatment of acute orofacial infections in general dental practice. Br Dent J 1989; 166: 41–45.

Barker G R, Qualtrough A J . An investigation into antibiotic prescribing at a dental teaching hospital. Br Dent J 1987; 162: 303–306.

Palmer N O A, Martin M V . An investigation of antibiotic prescribing by general dental practitioners: a pilot study. Primary Dent Care 1998; 5: 11–14.

Palmer N O A, Ireland R S, Palmer S E . Antibiotic prescribing patterns of a group of general dental practitioners: results of a pilot study. Primary Dent Care 1998; 5: 137–141.

SPSS for Windows Base Version 9.0.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc, 1998.

Manpower tables. Eastbourne: Dental Practice Board, February 1999.

Kaner E F, Haighton C A, McAvoy B R . A telephone survey of general practitioners' reasons for not participating in postal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract 1998; 48: 1067–1069.

Pogrel M A . Antibiotics in general practice. Dent Update 1994; 21: 274–280.

Cawson R A, Spector R G . Clinical Pharmacology in Dentistry. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

Dental Practitioners Formulary 1996–1998 British National Formulary No 32. London: The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain and the British Medical Association.

Lewis M A O, MacFarlane T W, McGowan D A . Quantitative bacteriology of acute dentoalveolar abscesses. J Med Microbiol 1986; 21: 101–104.

Gill Y, Scully C . The microbiology and management of acute dentoalveolar abscess views of the British oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 26: 452–457.

Lewis M A O, MacFarlane T W, McGowan D A . A microbiological and clinical review of the acute dentoalveolar abscess. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 28: 359–366.

Lewis M A O, Parkhurst C L, Douglas C W, Martin M V, Absi E G, Bishop P A, et al. Prevalence of penicillin resistant bacteria in acute suppurative oral infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 1995; 35: 785–791.

Ingham H R, Hood F J, Bradnum P, Tharagonnet D, Selkon J B . Metronidazole compared with penicillin in the treatment of acute dental infections. Br J Oral Surg 1977; 14: 264–269.

Lewis M A O, McGowan D A, MacFarlane T W . Short-course high-dosage amoxicillin in the treatment of acute dentoalveolar abscess. Br Dent J 1986; 161: 299–302.

Fazakerley M W, McGowan P, Hardy P, Martin M V . A comparative study of cephadrine, amoxicillin and phenoxymethylpenicillin in the treatment of acute dentoalveolar infection. Br Dent J 1993; 174: 359–363.

Martin M V, Longman L P, Hill J B, Hardy P . Acute dentoalveolar infections: an investigation of the duration of antibiotic therapy. Br Dent J 1997; 183: 135–137.

Longman L P, Martin M V . The use of antibiotics in the prevention of post-operative infection: a reappraisal. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 257–262.

Olson A K, Edington E M, Kulid J C, Weller R N . Update on antibiotics for endodontic practice. Compend Continuing Educ Dent 1990; 11: 328–332.

Palmer N O A . Clinical audit of emergency out-of -hours service in general practice in Sefton. Primary Dent Care 1996; 3: 65–67.

Trope M . Clinical management of the avulsed tooth. Dent Clin North Am 1995; 39: 93–112.

Van Buchem F L, Knottnerus J A, Schrijnemaekers V J, Peeters M F . Primary care based randomised placebo-controlled trial of antibiotic treatment in acute maxillary sinusitis. Lancet 1997; 349: 683–687.

Faculty of General Dental Practitioners, Royal College of Surgeons, England. Adult antimicrobial prescribing in Primary Care for general dental practitioners (In Press).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palmer, N., Pealing, R., Ireland, R. et al. A study of therapeutic antibiotic prescribing in National Health Service general dental practice in England. Br Dent J 188, 554–558 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800538

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800538

This article is cited by

-

Effect of an educational intervention among Lebanese dentists on antibiotic prescribing: a randomized controlled study

Clinical Oral Investigations (2022)

-

Investigating acute management of irreversible pulpitis: a survey of general dental practitioners in North East England

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Antibiotic use and resistance: a nationwide questionnaire survey among French dentists

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2020)

-

A survey of prescribing practices by general dentists in Australia

BMC Oral Health (2019)

-

Antimicrobial prescribing by dentists in Wales, UK: findings of the first cycle of a clinical audit

British Dental Journal (2016)