Case 1 Jim is a five-year-old boy. He had toothache. Father had been told that a local dentist was 'good with children' and would be willing to see a child in pain at any time. An appointment was duly arranged. On entering the surgery the dentist took father aside and obtained Jim's dental and medical history. He then turned his attention to Jim. He explained how he would numb and then extract Jim's tooth. He allowed Jim to see and touch the forceps so that Jim would understand what was happening to him. Father had been impressed by the dentist's management skills and at Jim's next appointment decided to register his two other younger children for dental care with this dentist.

Case 2 Jessie arrived for her first appointment with her mother. She held tightly onto mother's hand refusing to leave her side. Jessie ignored the dentist's overtures and remained curled up on her mother's lap. With mother's agreement it was decided that Jessie would return to meet the dentist and dental nurse without any treatment being imposed upon her. Gradually over several visits Jessie left her mother's side and walked round the surgery. On one occasion she took the dentist's hand telling her that she had brought 'Dolly-dolly' who was not frightened of the dentist. Jessie climbed into the chair. At this fourth visit Jessie's teeth were examined and prophylaxis completed. Jessie had her treatment completed within several visits with her mother being present in the surgery at the time of treatment.

Case 3 Mother brought Maura to the surgery for the extraction of two upper premolar teeth for orthodontic reasons. Maura had previously coped well with dental treatment and it was decided that the teeth would be extracted immediately. After the extraction of one tooth Maura had a panic attack. She felt sick, faint and cried for mother. The intensity of the attack destroyed Maura's ability to accept any further treatment. It was decided to leave the other extraction for another time. A phone call from mother informed the dentist of Maura's psychological difficulties. As a three-year-old she had become so frightened and panicky of life in general that she had been referred to a child psychiatrist. Maura's old fears were returning. She was finding it difficult to leave her mother at any time and gradually becoming phobic of school. Mother had been so shocked by the return of Maura's anxieties that she felt that Maura would not be able to withstand the extraction of the other tooth. The intensity of Maura's panic attack had shocked both the dentist and mother. Maura was referred for secondary level hospital dental care.

Case 4 Sandra, aged 9-years-old, was considered to be a 'good' patient being quite compliant with the dental treatment provided for her by her dentist. She had had several restorations but seemed to have taken all these in her stride. Sandra's grandmother usually brought her to the dentist and remained with her during the operative procedures. However, for Sandra's last appointment her mother also came along and like grandmother sat in the surgery. As the dentist was about to drill Sandra's tooth, mother stated nervously, 'I just hate it!' Sandra froze, became tearful and it was impossible to continue treatment. A new appointment for Sandra was made. The intervening time interval allowed the dentist to reflect upon Sandra's reaction to her mother's previous verbal outburst. A phone call ensured that grandmother would bring Sandra on her next visit. This allowed Sandra to complete her dental care.

Case 5 The young dentist could not understand Peter's anxieties and felt irritated at the thought of treating him. She had tried many times to provide dental care but Peter had always refused. This latest appointment was his 'last chance'. Otherwise he would be referred elsewhere. Despite her sense of hopelessness about caring for Peter the dentist decided to speak to his mother and this proved fruitful. Peter had been so frightened at the thought of treatment that he had not slept for the previous three nights and vomited before leaving the house. Mother had told the dentist that she had told Peter that he 'must try hard', that she would be with him during treatment. After receiving this information the dentist felt less concerned about treating Peter knowing that mother was supportive of her treatment plans. The dentist asked Peter why he was so frightened and he responded by saying, 'It was the injection'. The dentist now spent some time explaining how his gum and tooth would be numbed. Peter's mother sat beside him, encouraging him and holding her son's hand tightly when the local anaesthetic was administered. Peter was given a face mirror with the instruction to raise his hand if he wanted the dentist to stop. These simple procedures (activities) helped Peter combat his fears of passivity. With the treatment alliance restored the course of treatment was completed.

Case 6 Janet a four-year-old girl arrived as an emergency patient. She clung to her mother and refused to let the dentist examine her. As the dentist put her hand up to touch Janet's swollen face, Janet started to cry.

Case 7 The woman dentist, who treated Nora was kind and patient, encouraging her through her treatment experiences and in this regard had been helped by Nora's mother. Nora was frightened by the dentist sitting behind her. Her mother remembered that when Nora was 4-years-old she had a general anaesthetic to have a tonsillectomy. For that operation a female anaesthetist had also sat behind Nora whilst administering the inhalation anaesthetic. This had been a traumatic experience for Nora.

Abstract

The argument for and against the presence of the mother in the surgery while her child undergoes a dental procedure has been contentious. Using a psychodynamic framework, this paper suggests that the mother's presence is necessary for the dentist-child relationship to function correctly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The interaction of dentists with their child patients is a very special type of dentist–patient relationship. Child patients do not decide to attend on their own accord. Their mothers will often have made this decision for them. It will be mother who makes all dental health decisions for her child — when her child will be brought for dental care, decides what foods her child will eat, who will supervise tooth- brushing with a fluoride toothpaste and whether or not her child receives fluoride supplements. Mother is an integral part of dental health care for children.

Given this background, it is surprising, then, that mother is often left in the waiting room. The issue of whether the mother should or should not stay with the child during dental treatment has become a hotly debated issue in paediatric dentistry.1 There are those who state that the accompanying adult must remain in the waiting room while others believe mother's presence in the surgery is essential. Antagonists state that the child will 'play up' in front of mother while supporters state that to separate child from mother increases anxiety and interferes with treatment compliance.2 The latter authors suggest that the mother's presence in the surgery allows the dentist to form a relationship with mother and child which strengthens compliance, treatment and preventive regimes (the treatment alliance).3

Why should the debate of mother in or out of the surgery stir up such strength of feeling within the dental profession? Perhaps the answer to this question is related to the dentist's interaction with mother and child. This is a special type of dentist–patient relationship in which the dentist has to care for two people — child and mother. The dentist–patient interaction, therefore, shifts from being a two person encounter to being a three person encounter.4 When mother is excluded from the surgery the dentist–child patient relationship reverts to a two person endeavour as with adult patients. The wish to retain this familiar pattern of treatment encounter may be proposed as a reason for the exclusion of mother. Using a psychodynamic framework together with the concepts of the real relationship, the treatment alliance and transference will assist in understanding the dentist–child patient relationship and demonstrate the case for the mother being in the dental surgery during operative dental treatment.

The psychodynamic theory of the dentist–child patient relationship

Models exist5 which help explain the dentist– child patient relationship. What is proposed here is a psychodynamic model which illustrates the quality of the interaction between dentist, child and parent during dental care. In addition this model helps in understanding the shift of feeling or attention which occurs when a dentist treats a child patient in the presence of the mother. Different aspects of the model provide appropriate explanations for this three person endeavour, thus allowing the dentist to use it to strengthen the treatment alliance and the child's ability to accept dental care.

The real relationship

The real relationship is an equal and unique relationship between two adults. What possible relevance can it have for the dentist–child patient interaction? A real relationship does exist in the treatment of the child patient. It exists between the dentist and the parent who brings the child for care. The parent has heard about the dentist's skills with small children and it is with the parent that the equality of the interaction must be maintained. In Case 1, Jim's toothache and his emergency treatment allowed the real relationship between the dentist and Jim's father to be forged. This resulted in Jim's younger siblings being registered for dental treatment with the dentist. Father in this scenario acted as an advocate for Jim.

The treatment alliance

The need to reduce the child's dental anxiety is the most important aspect of managing children in the dental surgery. The intensity of the child's anxiety acts to destroy any attempt to form a treatment alliance. Everything must be done to reduce the child's anxiety so that a treatment alliance with the dentist may be achieved. The child's anticipatory and separation anxieties must be reduced. The unwanted effects of mother's own worries and concerns must be dealt with as well as the child's fears of helplessness and abandonment which arise as a result of the dental treatment itself.

The mother is an integral part of treatment of a family because she will assist the dentist to reduce the sources of anxiety which contribute to her children's fears of dental care. Although mother's personality may affect her child's ability to cope with dental care, the mother who can withstand her own anxieties together with those of her child will help the dentist to form and strengthen the treatment alliance. Irrespective of whether the child presents with pain or not, the first step in treating children is by communicating and discussing treatment options with the mother. It is in this way that mother's help is invaluable.

Anticipatory dental anxiety

The mother will be able to help her child cope with the dental experience by reducing the level of anticipatory anxiety. She should tell her child where they are going shortly before the dental appointment. The child should be encouraged to ask questions and have any questions answered. Mother must be advised to bring her child to the surgery only a few minutes before the appointment time. At the dental surgery the dentist, by using simple techniques, as tell-show-do, reduces the child's uncertainty by explaining every clinical procedure.6 By the mother and dentist working in partnership, the child's anticipatory anxiety, whether based on previous traumatic dental experiences and/or fears of the unknown, will be reduced allowing the child to accept the treatment that is being offered.

Separation anxiety

Another source of child dental anxiety is the fear of being separated from the mother. Separation anxiety1,7,8 is often confused with shyness in small children and it has been shown to be a good indicator of dental anxiety in childhood.9,10 Separation anxiety must be reduced to a minimum and therefore the mother must be invited into the surgery with her child.

In Case 2, the dentist's awareness of three-year-old Jessie's separation fears together with the help of the mother assisted in building up a treatment alliance. For several visits no dental treatment occurred as Jessie's 5-minute visits deliberately coincided with lunch-time breaks. In terms of time expended it was well spent. Jessie's restorative treatment was easily completed and resulted in a number of new families being registered at the practice.

For Jessie, aged three, the degree of separation anxiety1,8 was to be expected in a child at her stage of psychological development. For Maura, aged ten (Case 3), the inappropriateness and intensity of her separation fears were indicative of her considerable psychological difficulties.1 Her separation anxiety was so great that she was unable to leave her mother at anytime. Mother's presence in the surgery did little to alleviate the intensity of Maura's anxieties. Indeed the extraction of an upper premolar provided the necessary stimulus to precipitate a panic attack. The intensity of the anxiety Maura experienced destroyed the treatment alliance.

Maternal dental anxiety and the treatment alliance

Difficulties in child patient management may occur when the mother is too anxious and herself too frightened of dental treatment. Although some mothers are able to contain their dental fears, there are those who experience such an intensity of effect that it increases their child's anxiety and disturbs the developing treatment alliance. The infectiousness of maternal anxiety is observed in children who are dentally phobic. Their mothers are themselves dentally phobic and often admit to having psychological difficulties.11 The destruction of the treatment alliance reflects the intensity of anxiety experienced by the child which is compounded by the mother's dental anxiety status. In such cases it is better for the child to come with the father or indeed another close relative who is less fearful and with whom the child feels comfortable and safe. This was the situation when mother accompanied Sandra (Case 4) for restorative treatment.

Fears of passivity and helplessness

There is another source of anxiety which must be dealt with for the child to accept dental care. A possible source of anxiety arises from the fact that the child has to lie passively on the dental chair during treatment. This enforced passivity causes a sense of helplessness and abandonment.

The sense of helplessness in lying on a dental chair can be so intense that it interferes with the treatment alliance. It may be exacerbated by occupational anxieties arising within the dental practitioner.12 In case 5 the intensity of Peter's dental anxiety was such that it upset the treatment alliance. Peter's anxiety disturbed the young woman dentist who initially reacted to him in a brusque manner. Mother's interventions helped in his treatment.

The sense of helplessness and passivity must be lessened if the child is to be able to accept dental treatment. The child must be helped to turn the passive experiences of treatment into actions. For example the child can be asked to hold a face mirror so that (s)he can see what is happening inside the mouth. With other children the activity may take the form of 'playing dentist'. A small plastic mirror allows them to act the anticipated, fearful treatment experiences and this lessens helplessness and fears of abandonment. With mother's help in assisting her child 'play dentist' at home, the child's anticipatory anxiety will also be further reduced thereby strengthening the treatment alliance and the child's acceptance of dental care.12,13

Transference and regression

The interaction between the dentist and the adult patient is characterised by transferences and regression. The transference, for adults is a repetition of previously emotionally important relationships inappropriately (and automatically) imposed upon the person of the dentist. It is associated with regression which is reflected in a shift in the patient's attitudes. An equivalent situation does not exist in children. While children may regress in their ability to function, it is not true to say that a transference, of the type observed with adult patients, occurs in children, as the child is still attached to the mother. In children regression is more specific being related to the physical discomfort of dental treatment, pain of toothache and fears of dental treatment. The role of this regression is to reduce the child's age-adequate functioning in terms of psychological development, coping skills, cognition and motility. In other words, the child patient may be chronologically ten years old but as a consequence of regression may appear from their manner and behaviour to be much younger.

The discomfort of dental treatment as the cause of regression

Anna Freud14 stated that any physical discomfort acts as a regressive agent in children. In the case of seven-year-old Jo, a combination of her dental anxiety together with the discomfort of having her teeth fissure sealed, resulted in regression. This was observed in her behaviour (clinging to mother), her manner (she became incommunicable) and in her motility (she was motionless). She appeared much younger than her true age.

The discomfort of dental pain as the cause of regression

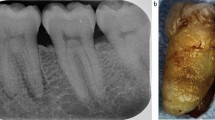

Mother's discovery of her child's abscessed tooth and swollen face had been a shock to both of them (Case 6). Janet was understandably distressed by her 'sore face' and consequently clung to her mother. According to mother, Janet was an outgoing child but since she had been unwell with toothache she had not let mother out of her sight and it became clear that Janet had regressed in her behaviour. Furthermore Janet was suffering with the pain of her abscessed tooth. When approached by the dentist Janet could not differentiate between the suffering caused by her dental abscess and the 'suffering' caused by the treatment to cure it.14

Dental anxiety as a stimulus for regression

The case of 14-year-old Nora illustrates how dental anxiety acts as a stimulus for regression (Case 7). Nora's mother always accompanied her for dental treatment and despite her considerable anxieties Nora managed to undergo any treatment required. She was nevertheless consumed with feelings of shame and humiliation, particularly when she thought about how she felt and behaved in the dental surgery, it made her feel like a baby. In this instance a false connection15 was made between a female doctor, wearing a white coat, sitting behind Nora and the female dentist who wore a white coat, and sat behind Nora when administering dental treatment.

Conclusions

This article sets out the case for the child's mother being present during treatment in the dental surgery. It illustrates how the mother is an integral part of child patient dental care. It is with the mother that the dentist forms the real relationship and it is through her that the treatment alliance between the dentist and the child is created and strengthened. For the child and dentist the mother is the greatest ally in terms of management.

References

Guthrie A . Separation anxiety: an overview. Pediatric Dentistry 1997; 19: 486–490.

Wright G Z, Starkey P E, Gardner D E . Parent–child separation. In G Z Wright, P E Starkey, D.E Gardner (Eds.) Managing Children's Behaviour in the Dental Office. St Louis. Mosby, 1983.

Frankl S N, Shiere F R, Fogels H R . Should the parent remain in the operatory? ASDC J Dent Child 1962; 29: 150–162.

Kamp A A . Parent child separation during dental care: a survey of parent's preference. Pediatric Dentistry 1992; 14: 231–235.

Robert J F . How important are techniques? The empathetic approach to working with children. J Dent Child 1995; 62: 38–43.

Carson P, Freeman R . Tell-show-do: Reducing anticipatory anxiety in emergency paediatric dental patients. Int J Health Prom Edu 1998; 36: 87–90.

Blinkhorn A S . Introduction to the dental surgery. In R R Welbury (Ed.) Paediatric Dentistry. Oxford. Oxford University Press. 1997.

Bowlby J, Robertson J, Rosenbluth S . A two and half-year-old goes to the hospital. The Psychoanal Stud Child 1952; 7: 82–94.

Holst A, Hallonsten A-L, Schroder U, Ek L, Edlund K . Prediction of behavior-management in 3-year-old children. Scand J Dent Res 1993; 101: 110–114.

Quinonez R, Santos R G, Boyar R . Temperament and trait anxiety as predictors of child behavior prior to general anesthesia for dental surgery. Ped Dent 1997; 19: 427–431.

Corkey B, Freeman R . Predictors of dental anxiety in 6 year-old children- a report of a pilot study. ASCD J Dent 1994: 61: 267–271.

Marcum B K, Turner C, Courts F J . Pediatric dentists' attitudes regarding parental presence during dental procedures. Ped Dent 1995; 17: 432–436.

Radis F G, Wilson S, Griffen A L, Coury D L . Temperament as a predictor of behaviour during initial dental examination in children. Ped Dent 1994; 16: 121–126.

Freud A . (1952) The role of bodily illness in the mental life of children. In R Ekins, R Freeman (Eds.) The Selected Writings of Anna Freud. Harmondsworth, Penguin Books. 1998.

Freeman R . A psychodynamic theory for dental phobia. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 170–176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

*The author recognises that fathers, grandparents, other relatives and/or family friends accompany children to the dentist. The noun mother will be used throughout to represent the accompanying adult.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freeman, R. The case for mother in the surgery. Br Dent J 186, 610–613 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800177

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800177