Abstract

The hedgehog (Hh)-signaling pathway plays an essential role in normal development. Deregulation of this pathway is responsible for several types of cancers. The aim of this study was to determine the expression pattern and the extent of Hh-signaling molecules in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix and its precursor lesions. A total of 106 uterine cervical cancers and related lesions (37 squamous cell carcinomas, 23 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) III, 10 CIN II, four CIN I, 32 normal cervical epithelia) were immunohistochemically analyzed with anti-Shh, Indian Hh (Ihh), Patched (PTCH), Smoothened (Smo), Gli-1, Gli-2, Gli-3 antibodies on paraffin blocks. The results showed that the expression of all the Hh-signaling molecules was greatly enhanced in uterine cervical tumors, including carcinoma and its precursor lesions. The staining pattern was mainly cytoplasmic except for Gli-1/2, whose expression was observed in both cytoplasm and nucleus. In case of Ihh, PTCH, Smo and Gli-1, their expression in normal epithelium was completely absent or rare. The expression of all the seven Hh-signaling molecules mentioned above was significantly increased in CIN II/III and carcinoma, compared with that in normal epithelium (P<0.05). The expression of Shh was increased by double; the first increase occurred in normal epithelium–CIN transition, and the second, during the progression of CIN to carcinoma. These results strongly suggest that the Hh-signaling pathways were extensively activated in carcinoma and CIN of uterine cervix. In conclusion, the Hh-signaling pathways may be involved in carcinogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix and can be considered as a potential therapeutic target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Hedgehog (Hh) is a family of secreted proteins and the Hh-signaling pathway has been known to play central roles in directing the embryonic pattern formation during development and to be involved in the regulation of stem cell renewal in adult tissue.1 In human development, the Hh-signaling pathway is crucial for the decision making of left-right asymmetry and patterning of various organs including the brain, spinal cord, craniofacial structures, lung, teeth, eye, and hair. However, during the postembryonic period, the Hh-signaling pathway has been known to be involved in the regulation of adult tissue stem cells during the regeneration of adult tissue after damage.1, 2, 3, 4

In mammals, three hedgehog (Hh) homologues have been identified: Sonic (Shh), Indian, and Desert. The Hh proteins activate a membrane–receptor complex and this, in turn, by means of cytoplasmic signal transduction, activates Gli zinc-finger transcription factors. The receptor complex is formed by Patched (PTCH) and Smoothened (Smo), where PTCH normally inhibits Smo. When Hh binds to PTCH, this repression of Smo by PTCH is released, allowing Smo to activate the Gli protein.5 The Gli proteins are large and multifunctional transcription factors, and there are three Gli proteins that behave differently with partially redundant functions; Gli1 and Gli2 can mediate Hh signals and have been implicated in tumorigenesis. Gli-1 is known to function primarily as an oncogene if tumors arise due to overexpression. On the other hand, Gli-2 and Gli-3 function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors, depending on the type of mutation and cellular context.6

The deregulation of Hh-signaling pathway has been implicated in several types of cancers.2, 3, 4 The mutational activation of the Hh-signaling pathway, whether sporadic or in Gorlin's syndrome, is associated with tumorigenesis in a small subset of these tissues, predominantly skin, the cerebellum, and skeletal muscle.7, 8 Furthermore, extensive activation of the Shh-signaling pathways has been reported in cancers of other organs, such as small cell lung cancer,9, 10 carcinomas of esophagus, stomach, pancreas, biliary tract, and prostate,1 and colonic neoplasia.11

Approximately 10 370 new cases of cervical cancers and 3710 deaths were anticipated in the United States in 2005.12 Cervical cancer is also an important health problem in adult women in developing countries, where it is the most or second most common cancer among women.13 Cervical cancer claims the lives of 231 000 women annually worldwide.13 Even a conservative estimate of the global prevalence suggests that there are 1.4 million cases of clinically recognized cervical cancer each year. It is also estimated that 3–7 million women worldwide may have high-grade dysplasia.13

Although the importance of the Hh signaling in tumor development is recognized in various organs, there has been no study regarding the expression of Hh-signaling molecules in uterine cervical tumors.

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the expression of Hh-signaling molecules at the protein level via immunohistochemistry in uterine cervical cancer and its precancerous lesions. The results demonstrated that the increased and persistent expression of Hh-signaling molecules may be implicated in carcinogenesis of uterine cervix.

Materials and methods

Patients, Tissue Samples, and Reagents

We investigated 106 cases of uterine cervical carcinomas and their related lesions, obtained from the surgical pathology files at the Department of Pathology, Chungbuk National University Hospital. The criteria for inclusion were the histopathologic diagnosis of uterine cervical lesions and the availability of paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. The selected cases consisted of 37 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, 23 cases of CIN III, 10 cases of CIN II, four cases of CIN I, and 32 cases of normal cervical epithelium. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chungbuk National University Hospital.

The pathologic slides were reviewed to analyze pathologic parameters, including tumor size, depth of invasion, and the presence of nodal metastasis. The 37 squamous cell carcinomas (age range=22–69 years; average age=46 years) encompassed 29 early cases (pTNM stage I=27, pTNM stage II=2) and eight advanced cases (pTNM stage III=8). The TNM staging was assessed according to the staging system established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).14

Tissue microarray slides were employed for the purpose of effective detection. For preparation of these slides, we punched tissue columns (3.0 mm in diameter) from the original blocks and inserted them into new paraffin blocks (each containing 30 holes to accept the tissue columns). Consequently, serially sectioned slides were prepared. Each tissue microarray slide (1 × 3 in) could hold 30 specimens, allowing us to analyze 30 specimens simultaneously with a minimum variation during the staining process. Each specimen was round in shape and 3.0 mm in diameter, thereby providing a sufficient amount of tissue for histopathologic analysis.

All archival materials were routinely fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm) were prepared on silane-coated slides (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The immunostaining kits were purchased from DAKO Inc. (Glostrup, Denmark).

The Immunohistochemical Staining Procedure

The tissue sections in the microslides were deparaffinized with xylene, hydrated in serial dilutions of alcohol, and immersed in 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were then microwaved in 40 mM Borate buffer (pH 8.2) supplemented with 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM NaCl for 20 min for antigen retrieval.15, 16 Tris-EDTA buffer (Tris 40 mM, EDTA 1 mM, pH 10.0) was also used as a retrieval buffer. The tissues were then incubated with several primary antibodies (anti-Shh, anti-Ihh, anti-PTCH, anti-Smo, anti-Gli1, anti-Gli2, and anti-Gli3). The dilution ratio and optimal retrieval buffer of each antibody are shown in Table 1. Primary antibody incubation was carried out for 60 min, followed by three successive rinsings with a washing buffer. Further incubation was performed with dextran polymer conjugated with peroxidase and goat anti-rabbit Ab (DAKO, Envision plus) for an additional 20 min at room temperature. After rinsing, the slides were washed and the chromogen was developed for 5 min with liquid 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DiNonA, Seoul, South Korea). The slides were counterstained with Meyer's hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with Canada balsam for examination. We used distilled water with 0.1% tween 20 as a rinsing solution.17

Evaluation of Results of Immunohistochemical Staining

We used the Sinicrope et al's18 scoring method (1995) to evaluate both the intensity of immunohistochemical staining and the proportion of the stained epithelial cells. The staining intensity was subclassified as follows: 1, weak; 2, moderate; or 3, strong. The positive cells were quantified as a percentage of the total number of epithelial cells and the proportions were assigned to one of five categories: 0, <5%; 1, 5–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; and 4, >75%. The percentage of positivity of the tumor cells and the staining intensity were then multiplied in order to generate the immunoreactivity score (IS) for each of the tumor specimens. Cytosolic and nuclear stainings were independently analyzed. Each lesion was separately examined and scored by two pathologists (XYH and SHK). Cases with discrepant scores were discussed to obtain a consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Fisher's exact tests, Pearson's χ2 tests, ANOVA, Mann–Whitney tests, Kruskal–Wallis test, Tukey's HSD, and Duncan's test (as a post hoc test). P-values <0.05 were regarded to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The Expression Pattern of Hh-Signaling Molecules in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Uterine Cervix and Its Precursor Lesions

We analyzed the expression pattern of Hh-signaling molecules (ie Shh, Indian Hh (Ihh), PTCH, Smo, Gli-1, Gli-2, Gli-3) in squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions of uterine cervix via immunohistochemistry. First, the average intensity was analyzed (the mean of IS from immunostaining). Then the Shh expression in terms of the rate of high expression was analyzed.

Shh expression

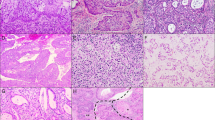

In case of Shh, the expression was observed in the cytoplasm of both glandular component and squamous epithelium of normal uterine cervical epithelium; however, the level was low (IS: 1.5±1.1). In squamous epithelium of the cervix, Shh was mainly expressed in basally located cells (Figures 1 and 2). However, its expression level was significantly increased in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN I, IS: 3.5±1.9; CIN II, IS: 3.4±1.2; CIN III, IS: 3.8±1.5) compared with in normal epithelium (IS: 1.5±1.1) (P<0.005) (Figures 1 and 3, Table 2). The level of Shh expression was also increased significantly in squamous cell carcinoma (IS: 5.7±1.5) compared with in CINs with a statistical significance (P<0.001) (Figures 1 and 3, Table 2). We also analyzed the Shh expression in terms of the rate of high expression, which was defined by IS higher than 3 (Table 3). In normal epithelium Shh high expression was rare (3/32, 9%). The rate was significantly increased in CIN (CIN I: 2/4, 50%. CIN II: 6/10, 60%. CIN III: 15/22, 68%) and even higher in carcinomas (35/37, 95%) (P<0.001) (Table 3).

A schematic representation of the expression of Hh-signaling molecules in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix and its related lesions; NL, normal uterine cervical epithelium; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Gli-1(C), cytoplasmic staining of Gli-1; Gli-1(N); nuclear staining of Gli-1; Gli-2(C), cytoplasmic staining of Gli-2; Gli-2(N); nuclear staining of Gli-2; Gli-3(C), cytoplasmic staining of Gli-3; Gli-3(N); nuclear staining of Gli-3. The expression level of individual cases of each disease entity represented by immunoreactivity score (IS) is shown in colors.

Ihh expression

The Ihh expression was very rare and almost completely absent in normal uterine cervical epithelium. However, aberrant expression of Ihh was frequently observed in CIN II, CIN III and squamous cell carcinoma (Figures 1 and 3). The level of Ihh expression was significantly increased in CIN II (IS: 2.0±1.5), CIN III (IS: 2.7±1.5) and carcinoma (IS: 2.9±2.4), compared with in normal epithelium (IS: 0.1±0.4) (P<0.001) (Table 2). The rate of high expression (IS>3) was zero in normal epithelium (0/25) and was significantly increased in CIN III (6/22, 27%) and carcinoma (13/37, 35%) (P<0.05) (Table 3).

PTCH expression

In normal epithelium PTCH was expressed in 5 of 25 cases (20%) (Figure 1). The average staining intensity (IS) increased significantly in CIN II (IS: 2.0±1.5), CIN III (IS: 2.7±1.5), and carcinoma (IS: 2.9±2.4), compared with normal epithelium (IS: 0.1±0.4) (P<0.001) (Table 2). The rate of high expression (IS>3) was low in normal epithelium (0/25, 0%) and CIN II (1/9, 11%), but substantially and significantly increased in CIN III (11/22, 50%) and carcinoma (22/37, 60%) with a statistical significance (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Smo expression

Smo expression was also rare and was found in only two out of 27 cases (Figure 1). The average intensity was extremely low in normal epithelium (IS: 0.1±0.3) and was significantly increased in neoplastic lesions including CIN I/II/III (IS: 2.7±1.5/2.6±2.1/2.1±1.7, respectively), and carcinoma (IS: 3.2±2.4) (P<0.001) (Figures 1 and 3, Table 2). The rate of high expression (IS>3) was also zero in normal epithelium (0/27, 0%), but was increased significantly in tumorous lesions such as CIN I (1/3, 33%)/CIN II (4/9, 44%)/CIN III (5/21, 24%) and carcinoma (18/37, 49%) (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Gli-1 expression

In contrast to the other Shh-signaling molecules whose expressions were observed mainly in cytoplasm, Gli-1/2 molecules were expressed in both cytoplasm and nucleus. The cytoplasmic expression of Gli-1 was completely absent in normal epithelium, but aberrant expression of the protein was frequently observed in CIN II/III and carcinoma (Figure 1). The average intensity of cytoplasmic Gli-1 expression significantly increased in CIN II (IS: 1.6±1.3)/CIN III (IS: 2.6±1.6) and carcinoma (IS: 1.9±1.7), compared with in normal cervical epithelium (IS: 0.0±0.0) (P<0.001) (Table 2). The rate of high cytoplasmic expression (IS>3) was zero in normal epithelium (0/29) and CIN I/II (0/3 and 0/8), but significantly increased in CIN III (7/23, 30%) and carcinoma (8/36, 22%) (P<0.01) (Table 3).

The nuclear expression of Gli-1 was very weak and rare in normal cervical epithelium (Figures 1 and 2). The average intensity of nuclear expression significantly increased in CIN II (IS: 2.3±2.3)/CIN III (IS: 1.4±1.5) and carcinoma (IS: 1.0±1.3), compared with in normal epithelium (IS: 0.1±0.3) (P<0.001) (Table 2). The rate of high nuclear expression (IS>3) was generally low in overall cervical lesions without a significant difference (Table 3).

Gli-2 expression

The cytoplasmic expression of Gli-2 was completely absent in normal epithelium, but aberrant expression of the protein was frequently noted in CIN II/III and carcinoma in the same manner as in Gli-1 (Figures 1 and 2). The average intensity of cytoplasmic Gli-2 expression significantly increased in CIN II (IS: 1.1±1.4)/CIN III (IS: 1.1±1.2) and carcinoma (IS: 1.1±1.3), compared with in normal epithelium (IS: 0.0±0.0) (P<0.001) (Table 2). The rate of high cytoplasmic expression (IS>3) was generally low in overall cervical lesions without a significant difference (Table 3).

The nuclear expression of Gli-2 was very abundant in normal epithelium in contrast to cytoplasmic staining (Figure 1). Nuclear staining was also found in endocervical glands as well as squamous epithelium. The average intensity of nuclear expression significantly increased in CIN I (IS: 6.8±1.0)/CIN II (IS: 7.7±1.4)/CIN III (IS: 8.2±2.3) and carcinoma (IS: 8.2±2.4) (P<0.001), compared with in normal epithelium (IS: 4.9±1.6) (Table 2). The rate of high nuclear expression (IS>7) was low in normal epithelium (3/29, 10%), but significantly increased in CIN II/III (5/8, 63% and 16/22, 73% respectively) and carcinoma (26/38, 68%) (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Gli-3 expression

In contrast to Gli-1/2, the majority of Gli-3 expression was cytoplasmic. The nuclear expression was observed in only three cases out of 36 carcinomas. There was no nuclear expression in the normal epithelium and CIN I/II/III lesions (Figure 1). Conversely, the cytoplasmic expression of Gli-3 was relatively abundant in normal epithelium. Cytoplasmic staining was also focally found in endocervical glands as well as in squamous epithelium. The average intensity of cytoplasmic expression was significantly increased in CIN II (IS: 4.1±2.0)/CIN III (IS: 5.6±2.0) and carcinoma (IS: 5.8±2.1), compared with normal epithelium (IS: 0.8±0.9) (P<0.001) (Table 2). And the average intensity of Gli-3 cytoplasmic expression in carcinoma was significantly higher than in CIN I/II (P<0.05). On the other hand, the rate of high cytoplasmic expression (IS>3) was zero in normal epithelium (0/25, 0%), but significantly increased in CIN II/III (5/8, 63% and 18/22, 82%, respectively) and carcinoma (30/36, 83%) (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the expression pattern of Hh-signaling molecules via immunohistochemistry in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix and its precursor lesions. Our results are summarized in Table 3 and indicate that the expression of Hh-signaling molecules is greatly enhanced over the whole normal epithelium-CIN I/II/III-carcinoma sequence in the uterine cervix. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of expression of Hh-signaling molecules in carcinoma and CIN of uterine cervix. The expression of all Hh-signaling molecules is upregulated in neoplastic lesions including CIN and carcinoma, compared with normal epithelium. The expression of Ihh, PTCH, Smo, and Gli-1 was completely absent or rare in normal epithelium, whereas frequent and aberrant expression of these molecules was observed in neoplastic lesions. These results strongly suggest that the Hh-signaling pathway was extensively activated in carcinoma and CIN of uterine cervix.

There has been no study regarding the expression of Hh-signaling molecules in uterine cervix. The significance and functional implication of the Hh-signaling pathway in normal uterine cervical epithelium are unknown. Based on our results, it is postulated that the Hh–Gli-signaling pathway is not functioning in normal cervical epithelium despite the prevalent expression of Shh and Gli-2,3 because of absence or very rare expression of PTCH and Smo, which are major mediators in the Hh signaling. Instead, it is possible that Shh may affect other uncharacterized signaling pathways rather than the Shh–Gli pathway, and Gli-2 may also be regulated by other signaling pathways such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling2 in normal cervix. The functional significance of Gli-3 as a transcription factor is questionable because its expression was relatively restricted to the cytoplasm instead of nucleus.

In the neoplastic lesions, the expression of PTCH and Smo were dramatically increased. Thus, it can be postulated that the Hh–Gli pathway is established. The significance of the Hh-signaling pathway in neoplastic lesions of uterine cervix is still elusive. Generally, the Hh-signaling pathways are known to function postembryonically in stem cell renewal, tissue repair, and regeneration. When aberrantly and persistently activated by chronic tissue injury, this pathway may play an important role in the initiation and growth of cancer.1 Hence, the Hh-signaling pathway as well as WNT signaling can be considered as a potential link between chronic tissue injury and cancer. The first link between Hh signaling and tumor formation was noted in patients with a familial cancer syndrome, basal cell-nevus syndrome (Gorlin's syndrome) that is associated with a PTCH mutation.2 Familial PTCH mutations that activate the Hh pathway have been associated with an increased incidence of cancers in brain, skin, skeletal muscle in humans and mice. Additional studies in which the Hh pathway activities were antagonized by drugs such as cyclopamine, antibodies, and overexpression of negatively acting pathway components demonstrated an ongoing requirement for the Hh pathway activity in small cell lung cancer and carcinomas of esophagus, stomach, pancreas, colon, biliary tract, and prostate.1 In addition, a consistent expression of Gli2 and Gli3 was observed in breast carcinomas.2 It is intriguing that the Hh pathway activation in tissues that gives rise to non-Gorlin's tumors seems to be limited not by the ligand availability but by the responsiveness to the ligand. In normal prostate, the limiting factor for ligand responsiveness is Smo, which is not expressed in normal prostate tissue, and high-level activation of Hh pathway mediators including Smo occurs only in cancer cells. Collectively, these results are highly consistent with our findings.1

An important factor in the carcinogenesis of uterine cervix is HPV infection, especially in high-risk groups. E6 proteins derived from high-risk HPV (type 16, 18, or 31) inactivate p53 by enhancing its degradation through ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.19 It is intriguing that the hyperactivation of Hh–Gli signaling synergizes with loss of other tumor suppressor genes, especially p53. In other words, tumorigenesis in the Ptc+/− mice was greatly enhanced in a p53-null background.20 Therefore, exaggerated and inappropriate activation of the Hh-signaling pathway and inactivation of p53 by E6 proteins from the HPV may exert a synergistic effect on the carcinogenesis of uterine cervix.

Previously we observed a two-fold increase of Shh in gastric cancer.21 Shh expression is increased two-fold over the whole metaplasia–dysplasia early and advanced gastric carcinoma. The first increase was observed in metaplasia–dysplasia (adenoma) transition. The second occurred during the progression of early gastric cancer to advanced gastric cancer. This expression pattern is very similar to that observed in cervical neoplasia. The implications of these findings remain to be clarified. However, these results indicate that the role of Shh may change in a dosage-dependent manner and acquire additional tumor-promoting functions at higher expression.

LOH at the PTCH locus was detected in 15.6% of squamous cell carcinoma cases (5/32) of uterine cervix.22 LOH, as well as an elevation of mRNA level of PTCH was found in basal cell carcinoma (BCC). This indicates that constitutive activation of Shh–PTCH signaling is required for the development of BCC.23 It was reported that PTCH+/− mice have a higher incidence of squamous cell carcinomas after ultraviolet (UV) exposure, and the size of the tumor is also greatly increased.24 Therefore, it is possible to postulate that genetic alteration or deregulation of the expression of PTCH superimposed with another genetic alteration such as UV exposure or p53 alteration by HPV may play a role in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix.

Gli-1 is known to function primarily as an oncogene if tumors arise due to overexpression. However, Gli-2 and Gli-3 could function either as oncogenes or tumor suppressors, depending on the type of mutation and cellular context.6 However, Gli-2 is known to have a redundant function with Gli-1 and has been implicated in tumorigenesis.2 According to our results, Gli-2 may play a more important role than Gli-1. The Gli-1 expression in the nucleus is relatively frequent but is negative in a considerable portion of tumor cases, whereas nuclear expression of Gli-2 is strong and persistent in all tumor cases. The nuclear expression of Gli-3 is very rare in tumor cases. Thus, the role of Gli-3 as a transcription factor is considered minimal.

In summary, we demonstrated that the expression of Hh-signaling molecules is greatly enhanced in uterine cervical tumors including carcinoma and its precursor lesions. Although the functional significance of the Hh pathway remains to be determined in uterine cervical cancer, the Hh-signaling pathway may play an important role in tumorigenesis and could be a potential therapeutic target.

References

Beachy PA, Karhadkar SS, Berman DM . Tissue repair and stem cell renewal in carcinogenesis. Nature 2004;432:324–331.

Altaba ARi, Sanchez P, Dahmane N . Gli and hedgehog in cancer: tumours, embryos and stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:361–372.

McMahon AP . More surprise in the hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell 2000;10:185–188.

Wetmore C . Sonic hedgehog in normal and neoplastic proliferation: insight gained from human tumors and animal models. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2003;13:34–42.

Altaba ARi . Gli proteins and hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Trends Genet 1999;15:418–425.

Matise P, Joyner AL . Gli genes in development and cancer. Oncogene 1999;18:7852–7859.

Bale AE, Yu KP . The hedgehog pathway and basal cell carcinomas. Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:757–762.

Wechsler-Reya R, Scott MP . The developmental biology of brain tumors. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001;24:385–428.

Watkins DN, Berman DM, Burkholder SG, et al. Hedgehog signaling within airway epithelial progenitors and in small cell lung cancer. Nature 2003;422:313–317.

Kubo M, Nakamura M, Tasaki A, et al. Hedgehog signaling pathway is a new therapeutic target for patients with breast cancer. Cancer Res 2004;64:6071–6074.

Oniscu A, James RM, Morris RG, et al. Expression of Sonic hedgehog pathway genes is altered in colonic neoplasia. J Pathol 2004;203:909–917.

Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:10–30.

Sankaranarayanan R, Budukh AM, Rajkumar R . Effective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:954–962.

Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edn. Springer: Berlin, 2002, 139pp.

Kim SH, Kook MC, Song HG . Optimal conditions for the retrieval of CD4 and CD8 antigens in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J Mol Histol 2004;35:403–408.

Kim SH, Kook MC, Shin YK, et al. Evaluation of antigen retrieval buffer systems. J Mol Histol 2004;35:409–416.

Kim SH, Shin YK, Lee KM, et al. An improved protocol of biotinylated tyramine-based immunohistochemistry minimizing nonspecific background staining. J Histochem Cytochem 2003;51:129–132.

Sinicrope FA, Ruan SB, Cleary KB, et al. bcl-2 and p53 oncoprotein expression during colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 1995;55:237–241.

zur Hausen H . Cervical cancer: papilloma virus and p53. Nature 1998;393:217.

Wetmore C, Eberhart DE, Curran T . Loss of p53 but not ARF accelerates mdulloblastoma in mice heterozygous for patched. Cancer Res 2001;61:513–516.

Wang LH, Choi YL, Hua XY, et al. Expression of sonic hedgehog in gastric cancer and its related lesions and methylation as its regulating mechanism. Mod Pathol 2006;19:675–683.

Lu X, Nikaido T, Toki T et al. Loss of heterozygosity among tumor suppressor genes in invasive and in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2000;10:452–458.

Toftgard R . Hedgehog signaling in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 2000;57:1720–1731.

Aszterbaum M, Epstein J, Oro A, et al. Ultraviolet and ionizing radiation enhance the growth of BCCs and trichoblastomas in patched heterozygous knockout mice. Nat Med 1999;5:1285–1291.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xuan, Y., Jung, H., Choi, YL. et al. Enhanced expression of hedgehog signaling molecules in squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix and its precursor lesions. Mod Pathol 19, 1139–1147 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800600

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800600

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Aberrant activation of the Hedgehog signalling pathway in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva as a potential target for cancer therapy

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: Molecular mechanisms in progression of HPV-associated cervical carcinogenesis

Journal of Biomedical Science (2019)

-

Differential effects of GLI2 and GLI3 in regulating cervical cancer malignancy in vitro and in vivo

Laboratory Investigation (2018)

-

Cross-talk between Human Papillomavirus Oncoproteins and Hedgehog Signaling Synergistically Promotes Stemness in Cervical Cancer Cells

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Genes targeted by the Hedgehog-signaling pathway can be regulated by Estrogen related receptor β

BMC Molecular Biology (2015)