Abstract

Columnar cell lesions (CCLs) of the breast with low-grade/monomorphic-type cytologic atypia are being identified increasingly in biopsies performed owing to mammographic microcalcifications. The WHO Working Group on the Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast recently introduced the term ‘flat epithelial atypia’ (FEA) for these lesions. However, the ability of pathologists to reproducibly diagnose FEA and to distinguish it from CCLs without atypia has not been previously evaluated. Eight pathologists with an interest in breast pathology participated in a study to address this issue. The study reference pathologist provided the other seven study pathologists with a Powerpoint tutorial that included written criteria for, and representative images of, FEA and CCLs without atypia (ie, columnar cell change and columnar cell hyperplasia). Following review of the tutorial, the study pathologists examined images in Powerpoint format from 30 CCLs and were instructed to categorize each as either ‘FEA’ or ‘not atypical’. Overall agreement among the eight pathologists was 91.8% (95% CI, 84.0–96.9%), and the multi-rater kappa value was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.67–0.94), which is within the ‘excellent agreement’ range. Agreement was slightly better for determining absence of FEA (92.8%: 95% CI, 84.1–97.4%), than for determining its presence (90.4%: 95% CI, 79.9–96.7%). We conclude that the diagnosis of FEA and its distinction from CCLs without atypia is highly reproducible with the use of available diagnostic criteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Columnar cell lesions (CCLs) of the breast represent a spectrum of histologic alterations that have in common the presence of columnar epithelial cells lining variably enlarged terminal duct lobular units. These lesions range in appearance from those characterized by a single layer of cytologically banal columnar cells to those in which the columnar cells exhibit sufficient cytologic and/or architectural atypia to raise the question of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

CCLs were first recognized about a century ago1 and have subsequently been described by a number of authors under a wide variety of names.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Recently, there has been renewed interest in these lesions because they are being detected with increasing frequency in breast biopsies performed owing to mammographic microcalcifications. At this time, however, the lack of standardized terminology and the limited available information on their clinical significance has created difficulties with regard to both pathologic diagnosis of CCLs and the management of patients with these lesions.

Recent observational studies as well as emerging genetic evidence suggest that some CCLs, particularly those with low-grade/monomorphic-type cytologic atypia, represent precursors to, or an early stage in the development of, low-grade DCIS.7, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19 In fact, CCLs with cytologic atypia were initially recognized by Azzopardi as a form of DCIS that he designated ‘clinging carcinoma’.6, 7, 20 Subsequently, De Potter et al separated clinging carcinoma into two subtypes: clinging carcinoma with pleomorphic nuclei and clinging carcinoma with monomorphic nuclei.21 The latter subgroup of lesions would fall under the recently proposed term ‘flat epithelial atypia’ (FEA). This term was introduced by the WHO Working Group on the Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast16 to encompass CCLs with low-grade/monomorphic-type cytologic atypia that lacked the architectural features of atypical ductal hyperplasia or low-grade DCIS. Although the natural history of these lesions is poorly defined, prior studies have documented an association between FEA and the presence of synchronous atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), DCIS, invasive carcinoma (particularly, tubular carcinoma), and lobular neoplasia.3, 5, 22, 23 Therefore, the identification of FEA and its distinction from non-atypical CCLs is a matter of practical importance to surgical pathologists and will be important for future studies of these lesions. At this time, however, the ability of pathologists to reproducibly separate FEA from CCLs without atypia is unknown. As a first step toward addressing this issue, we conducted a study to determine if eight pathologists with an interest in breast pathology could reproducibly distinguish FEA from non-atypical CCLs using available diagnostic criteria for these lesions.

Materials and methods

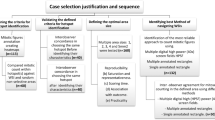

The study reference pathologist (SJS) prepared a tutorial in Powerpoint format that included written criteria for the diagnosis of columnar cell change and columnar cell hyperplasia (non-atypical CCLs) and for FEA, as well as representative digital images of each category of lesion. The diagnostic criteria for FEA used in this study were those adopted by the WHO Working Group on the Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast.16 The criteria for the non-atypical CCLs used were those proposed by Schnitt and Vincent-Salomon.13 These diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

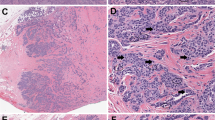

Columnar cell change. (a) Low power shows a terminal duct lobular unit with dilated acini. (b) At high power, these acini are lined by a single layer of columnar cells with nuclei that are ovoid, rather than rounded, in shape. Nucleoli are inconspicuous or absent. The cells are oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane in a ‘picket fence’ arrangement.

Columnar cell hyperplasia. (a) A dilated terminal duct lobular unit is evident at low power. (b) High power reveals stratification of the columnar cells with formation of small tufts. As in columnar cell change the cells are ovoid in shape, and although stratified, retain a perpendicular orientation to the basement membrane.

Flat epithelial atypia. (a) The dilated acini are lined by a few cell layers with no evidence of architectural complexity. The lumina contain flocculent secretions and minute calcifications. (b) The columnar cells, at high power, show low-grade cytologic atypia with rounded rather than ovoid nuclei. There is loss of orientation of the cells relative to the basement membrane. Apical snouts are present.

Flat epithelial atypia. (a) Medium power shows a variably dilated terminal duct lobular unit lined by cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. As in Figure 3, there is no evidence of architectural complexity, such as bridge formation or micropapillae. (b) The cells are atypical with rounded nuclei and nucleoli. Snouts are prominent.

Flat epithelial atypia. (a) In this example, the dilated acinus is lined by 1–2 cell layers and abundant intraluminal calcifications are present. (b) High power view shows cytologic atypia with a slight increase in nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, a monomorphic appearance to the cells and lack of orientation relative to the basement membrane.

Following review of this training tutorial, the other seven study pathologists were provided with a test set of 30 CCLs (also prepared by the reference pathologist) that consisted of a Powerpoint file containing digital images of each case (three images for 21 of the cases, two images for seven of the cases, and four images for two of the cases). The participants were instructed to categorize each case as either ‘FEA’ or ‘not atypical’. If a case was considered equivocal, the participants were instructed to place it in the ‘not atypical’ category.

The diagnoses of the reference pathologist and those of the other seven study pathologists were independently submitted directly to the study statistician (ME). The data were tallied and plotted, and unweighted multi-rater kappa statistics and percent agreement were calculated.24 Percent specific agreement for the presence and absence of FEA was also calculated.25 The 95% confidence intervals for kappa and percent agreement were obtained using the BCa bootstrap method,26 based on 1000 bootstrap samples.

Results

The overall agreement among the eight pathologists for the 30 cases was 91.8% (95% CI, 84.0–96.9%) and the multi-rater kappa value was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.67–0.94), which is within the ‘excellent agreement’ range. Complete agreement among all eight pathologists was achieved in 24 cases (80.0%), at least seven pathologists agreed in 26 cases (86.7%), and six or more agreed in 28 cases (93.3%). Agreement was slightly better for determining the absence of FEA (92.8%: 95% CI, 84.1–97.4%), than for determining the presence of FEA (90.4%: 95% CI, 79.9–96.7%). Of the 14 cases of FEA diagnosed by the reference pathologist, all eight pathologists agreed on the presence of FEA in 10 (71.4%), six or more agreed on the presence of FEA in 12 (85.7%), five or more agreed on the presence of FEA in 13 (92.9%), and at least four agreed on the presence of FEA in all 14 cases (100%). Of the 16 cases that were classified as ‘not atypical’ by the reference pathologist, all eight pathologists agreed on the absence of FEA in 14 (87.5%) and seven or more pathologists agreed on the absence of FEA on all 16 cases (100%). These results are summarized in Figure 6. Representative cases are illustrated in Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12.

Case 21: flat epithelial atypia. (a) The exaggerated snouts in the cells lining this dilated space are evident at low power. (b) High power shows a monomorphic appearance to the atypical nuclei. Many cells have conspicuous nucleoli. There was unanimous agreement that this was flat epithelial atypia.

Case 28. This is another example where there was less than unanimous agreement; four pathologists recorded this as flat epithelial atypia and the remaining four categorized it as not atypical. (a) On low power, the cells lining the dilated spaces have a low grade, monomorphic appearance. (b) On high power, the cytologic atypia can be appreciated, although again the changes are very subtle.

Discussion

The identification of CCLs is becoming increasingly common in breast biopsies performed owing to mammographic microcalcifications. A subset of these lesions is characterized by enlarged terminal duct lobular units in which the acini are lined by one to several layers of cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells with low-grade/monomorphic-type cytologic atypia similar to that seen in low-grade DCIS. Lesions with this constellation of features have long been recognized by pathologists under a wide variety of names including atypical cystic duct,27 atypical lobules type A,4 clinging carcinoma,6, 20 hypersecretory hyperplasia with atypia,8, 10 small ectatic ducts lined by atypical ductal cells with apical snouts,5 columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions with atypia,3 atypical cystic lobules,9 ductal intraepithelial neoplasia-flat type,18 and columnar cell hyperplasia with atypia.11, 13 Most recently, the WHO Working Group on the Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast introduced the term ‘flat epithelial atypia’ (FEA) to describe these lesions.16 While this term may be no better than any that have been suggested before it, it is now part of the WHO classification of tumors of the breast and, as such, we believe that it is prudent for pathologists to use it in clinical practice and in research studies at least in addition to, if not in place of, any of the other names that have been used to describe this lesion in the past.

Emerging evidence suggests that FEA may have an important role in neoplastic progression in the breast.18, 19 Whereas its ultimate role in breast tumorigenesis remains to be more clearly defined, available observational data have indicated that FEA often coexists with other lesions for which the clinical implications and management considerations are better understood such as ADH, DCIS, invasive carcinoma (particularly tubular carcinoma) and lobular neoplasia.3, 5, 22, 23 Therefore, the recognition of FEA is of importance for surgical pathologists because this serves as a ‘red flag’, particularly in core biopsies, for the possible presence of these other lesions.

A number of prior studies have addressed the issue of interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of proliferative breast lesions.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 One conclusion that can be drawn from these studies is that observer agreement is fostered by the use of standardized histologic criteria by the study participants. In keeping with this observation, the results of this study demonstrate for the first time that FEA, as defined by the WHO Working Group, can be distinguished from non-atypical CCLs with a high degree of consistency using available diagnostic criteria. In fact, the level of agreement we observed among eight pathologists in this study was higher than that seen in prior studies of observer agreement in proliferative breast lesions, even those in which standardized criteria were employed.32

There are a number of potential limitations to this study. First, it could be argued that our results may not be representative of the level of agreement attainable in general pathology practice because all of the pathologists participating in this study have a particular interest in breast pathology. Second, the pathologists in this study were asked to render their diagnoses following examination of selected digital images rather than following examination of whole histologic sections under the microscope, as is done in routine clinical practice. However, given that the goal of this study was to assess observer variability in the classification of specific lesions, we believe that the use of digital images could be viewed as a strength of the study as this required the participants to base their diagnoses solely on the microscopic features of the lesions in question without the aid of surrounding histologic cues.

Criteria for the diagnosis of CCLs and FEA may continue to evolve as new knowledge about these lesions becomes available. However, the results of this study indicate that the diagnosis of FEA and its distinction from non-atypical CCLs (columnar cell change and columnar cell hyperplasia) is highly reproducible with the use of currently available diagnostic criteria. The use of these criteria in clinical practice and in future research studies evaluating the molecular biology and clinical significance of these lesions should help improve patient care and communication between pathologists and with clinicians, and should help advance our understanding of these lesions.

References

Warren JC . A plea for reciprocity as illustrated by the consideration of the classification and treatment of benign tumors of the breast. JAMA 1905;45:149–165.

Foote FW, Stewart FW . Comparative studies of cancerous vs non-cancerous breasts. Basic morphological characteristics. Ann Surg 1945;121: 6-53-197-222.

Fraser JL, Raza S, Chorny K, et al. Columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions: a spectrum of changes frequently present in breast biopsies performed for microcalcifications. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1521–1527.

Wellings SR, Jensen HM, Marcum RG . An atlas of subgross pathology of the human breast with special reference to possible precancerous lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst 1975;55:231–273.

Goldstein NS, O'Malley BA . Cancerization of small ectatic ducts of the breast by ductal carcinoma in situ cells with apocrine snouts: a lesion associated with tubular carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1997;107:561–566.

Azzopardi JG . Problems in Breast Pathology. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, 1978, pp 193–202.

Eusebi V, Feudale E, Foschini MP, et al. Long-term follow-up of in situ carcinoma of the breast. Semin Diagn Pathol 1994;11:223–235.

Kasami M, Jensen RA, Simpson JF, et al. Lobulocentricity of breast hypersecretory hyperplasia with cytologic atypia: infrequent association with carcinoma in situ. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;122:714–720.

Oyama T, Iijima K, Takei H, et al. Atypical cystic lobule of the breast: an early stage of low-grade ductal carcinoma in-situ. Breast Cancer 2000;7:326–331.

Page DL, Kasami M, Jensen RA . Hypersecretory hyperplasia with atypia in breast biopsies. Pathology Case Reviews 1996;1:36–40.

Schnitt S . Columnar cell lesions of the breast. Pathology Case Reviews 2003;8:201–210.

Schnitt SJ . The diagnosis and management of pre-invasive breast disease: flat epithelial atypia—classification, pathologic features and clinical significance. Breast Cancer Res 2003;5:263–268.

Schnitt SJ, Vincent-Salomon A . Columnar cell lesions of the breast. Adv Anat Pathol 2003;10:113–124.

Shaaban AM, Sloane JP, West CR, et al. Histopathologic types of benign breast lesions and the risk of breast cancer: case–control study. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:421–430.

Rosen PP . Rosen's Breast Pathology, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 2001.

Tavassoli FA, Hoefler H, Rosai J, et al. Intraductal proliferative lesions. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2003, pp 63–73.

Bijker N, Peterse JL, Duchateau L, et al. Risk factors for recurrence and metastasis after breast-conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 10853. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2263–2271.

Moinfar F, Man YG, Bratthauer GL, et al. Genetic abnormalities in mammary ductal intraepithelial neoplasia-flat type (‘clinging ductal carcinoma in situ’): a simulator of normal mammary epithelium. Cancer 2000;88:2072–2081.

Simpson PT, Gale T, Reis-Filho JS, et al. Columnar cell lesions of the breast: the missing link in breast cancer progression? A morphological and molecular analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:734–746.

Eusebi V, Foschini MP, Cook MG, et al. Long-term follow-up of in situ carcinoma of the breast with special emphasis on clinging carcinoma. Semin Diagn Pathol 1989;6:165–173.

De Potter CR, Foschini MP, Schelfhout AM, et al. Immunohistochemical study of neu protein overexpression in clinging in situ duct carcinoma of the breast. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1993;422:375–380.

Rosen PP . Columnar cell hyperplasia is associated with lobular carcinoma in situ and tubular carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1561.

Brogi E, Oyama T, Koerner FC . Atypical cystic lobules in patients with lobular neoplasia. Int J Surg Pathol 2001;9:201–206.

Fleiss JL . Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 1981.

Holman CD . Analysis of interobserver variation on a programmable calculator. Am J Epidemiol 1984;120:154–160.

Carpenter J, Bithell J . Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med 2000;19:1141–1164.

Tsuchiya S . Atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia and interpretation of a new borderline lesion. Jpn J Cancer Clin 1998;44:548–555.

Rosai J . Borderline epithelial lesions of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:209–221.

Palazzo J, Hyslop T . Hyperplastic ductal and lobular lesions and carcinoma in situ of the breast: Reproducibility of current diagnostic criteria among community and academic based pathologists. Breast J 1998; 4:230–237.

Bodian CA, Perzin KH, Lattes R, et al. Reproducibility and validity of pathologic classifications of benign breast disease and implications for clinical applications [see comments]. Cancer 1993;71:3908–3913.

Palli D, Galli M, Bianchi S, et al. Reproducibility of histological diagnosis of breast lesions: results of a panel in Italy. Eur J Cancer 1996;32A:603–607.

Schnitt SJ, Connolly JL, Tavassoli FA, et al. Interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of ductal proliferative breast lesions using standardized criteria [see comments]. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:1133–1143.

Sloane JP, Amendoeira I, Apostolikas N, et al. Consistency achieved by 23 European pathologists in categorizing ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast using five classifications. European Commission Working Group on Breast Screening Pathology. Hum Pathol 1998;29:1056–1062.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathologists meeting, San Antonio, 2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O'Malley, F., Mohsin, S., Badve, S. et al. Interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of flat epithelial atypia of the breast. Mod Pathol 19, 172–179 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800514

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800514

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Erythrophagocytosis is not a reproducible finding in liver biopsies, and is not associated with clinical diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

Virchows Archiv (2024)

-

Dimorphic cells: a common feature throughout the low nuclear grade breast neoplasia spectrum

Virchows Archiv (2023)

-

IV Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, Including its Histologic Subtypes and Grades

Current Breast Cancer Reports (2021)

-

Inter-observer reproducibility of classical lobular neoplasia (B3 lesions) in preoperative breast biopsies: a study of the Swiss Working Group of breast and gynecopathologists

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2020)

-

Columnar cell lesions of the breast: a practical review for the pathologist

Surgical and Experimental Pathology (2019)