Abstract

The cytologic diagnosis of malignancy is frequently straightforward. For difficult cases, multiple immunostains and immunostain panels have been investigated without consensus. β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) has been reportedly expressed in malignancies, but not in normal tissue. HCG also has been reported as a specific marker of metastases in serous fluids when detected with laboratory assays. We investigated the clinical utility of hCG in this cytologic setting. A total of 97 cases of benign and malignant effusions were studied. Each case was immunostained with monoclonal hCG using the avidin–biotin technique and diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Additionally, a mucicarmine stain was performed on most cases. Cases were evaluated for hCG expression and mucin in a blinded fashion. After the cases were reviewed, the diagnoses were unblinded and staining patterns were evaluated. Of the 47 benign cases studied, 23 (49%) exhibited immunoreactivity to hCG in at least 5% of mesothelial cells present. In contrast, 28 of 44 (64%) adenocarcionomas exhibited a similar degree of immunostaining. In all, 21 (48%) of the adenocarcinomas were also positive for mucin; five of these mucin-positive cases were negative for hCG. The combination of mucin and hCG detected 33 of 44 (75%) adenocarcinomas. We conclude that hCG lacks the specificity for malignant cells to be of clinical use in effusion cytology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

While the cytologic detection of carcinoma in serous effusions is often a straightforward diagnosis, difficulties can arise in the setting of reactive or inflamed mesothelium. Numerous studies have been published trying to define an optimal immunostain or immunostain panel to help resolve problematic cases. To date, no consensus has been reached in this regard.1, 2, 3, 4

β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is a hormone normally expressed in human placenta and trophoblastic tumors. Several carcinomas, in addition to trophoblastic tumors, may express hCG, and detection of serum hCG in patients with such carcinomas generally portends a poor prognosis.5, 6, 7 Additionally, detection of hCG in serous fluids using various laboratory assays has been associated with the presence of metastases in these specimens.8, 9 However, to date, no study has been published examining hCG as an immunostain in this cytologic setting.

We investigated the clinical utility of hCG as a diagnostic immunostain to detect malignant cells in the setting of effusion cytology.

Materials and methods

A total of 102 cases were selected from the archives of the Presbyterian Medical Center and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania from 1998 to 2001. Five were subsequently excluded for lack of cellular material, leaving 97 cases studied for this report. Some of these cases have been reported previously.10, 11, 12 In all, 47 cases were diagnosed as benign reactive mesothelium; the remaining cases were malignant. The malignant cases were primarily adenocarcinomas with a small number of other carcinomas and mesotheliomas. The case distribution is outlined in Table 1.

All cases were selected by the following criteria:

-

1

An unequivocal diagnosis of malignancy or benignity. Patients with a benign diagnosis had no history, clinical or radiological suspicion of malignancy. The diagnoses were rendered based on cellular morphology correlated, when possible, with previous surgical pathology material.

-

2

A cellular cell block containing diagnostic cells on the last H&E slide cut from the block with adequate material remaining in the block.

All specimens were fixed in formaldehyde prior to preparation for embedding in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry was performed using the avidin–biotin complex method on an Optimax Plus automated immunostainer (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA). Briefly, 4 μm sections on coated slides were deparaffinized in xylene for 10 min, and rehydrated in 100 and 95% alcohol. All slides were pretreated with an enzyme digestion (Digest-All 3, Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA, USA) for 15 min at 37°C. The enzyme was made fresh according to the manufacturer's instructions and the slides were washed with tap water and phosphate-buffered saline several times afterward. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using a hydrogen peroxide block (Dako, Carpenteria CA, USA) for 10 min. The hCG antibody (1:100 dilution, Zymed) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in a humidified environment. A polymer-labeled secondary antibody (Dako) was applied for 30 min followed by incubation with diaminobenzidine (Dako) as a chromogen and then counterstaining with hematoxylin. Placenta provided by the Co-operative Human Tissue Network (a division of the National Cancer Institute) served as a positive control. Mucin staining was also performed in 46 malignant cases and 23 benign cases using Mayer's mucicarmine staining technique.

Slides were graded by one of the authors (RLZ) in a blinded fashion for granular cytoplasmic staining that was distinct and clearly stronger than background staining. Identifying such staining in at least 5% of tumor cells rendered the case positive. Staining that was not unequivocally distinct from background staining was considered negative, as this was likely residual endogenous peroxidase activity.

Results

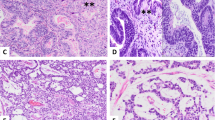

Of the 47 benign cases studied, 23 (49%) exhibited immunoreactivity to hCG in at least 5% of mesothelial cells present (Figure 1). In contrast, 28 of 44 (64%) adenocarcionomas exhibited a similar degree of immunostaining (Figure 2). Each single case of neuroendocrine carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma were negative. Two of four (50%) mesotheliomas immunostained for hCG. A total of 21 (48%) of the adenocarcinomas were also positive for mucin; five of these mucin-positive cases were negative for hCG. The combination of mucin and hCG detected 33 of 44 (75%) adenocarcinomas. No benign cases or mesotheliomas exhibited mucin production. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

The detection of malignant cells in serous effusions carries significant prognostic and therapeutic implications. Of particular concern is detecting cancer cells while a patient is actively undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Unfortunately, mesothelial cells exhibit reactive atypia in response to such adjuvant therapies and may be mistaken for malignant cells. Immunocytochemistry has been studied extensively as a means of resolving this diagnostic dilemma, but there is no consensus regarding an optimal staining combination.1, 2, 3, 4

HCG is a hormone expressed in large quantities in human placenta. Use of hCG as a laboratory test for diagnosing pregnancy, screening for trophoblastic disease and germ cell tumors is well established. Additionally, several carcinomas express hCG in addition to various germ cell tumors. The detection of hCG in serum in patients with carcinoma usually indicates a poor prognosis5, 6 or disease progression.13 Similarly, tumors expressing hCG in colorectal adenocarcinoma suggests an aggressive course.14 Of interest for this study is the observation that normal tissue, for example oral mucosa, does not express hCG.15 Past experiments have also shown that detecting hCG in serous fluids or urine using laboratory methods indicates the presence of malignancy in these specimens.7, 8, 16 Prior reports indicate that 31–42% of malignant effusions will have elevated hCG levels as compared to benign effusions using laboratory methods. The specificity of hCG as a laboratory test for malignant effusions is reported to be over 90%. However, using hCG as an immunostain has not been widely examined as a diagnostic adjunct.

Data presented here indicate that hCG is not clinically useful as an immunostain in effusion cytology. Specifically, 49% of reactive mesothelium exhibited immunoreactivity as compared to 64% of malignant cases. The low sensitivity of hCG to detect carcinoma may be explained by the variability of hCG expression in malignancies. Alternatively, the relatively low sensitivity of hCG may be secondary to the variable glycosylation of hCG in tumors that, in turn, may alter the epitope structure of the hormone.17 Normal tissue is not thought to express hCG, although low levels of hCG detected in benign effusions in this study suggest there may be some expression in reactive or reparative mesothelial tissue. Why hCG would be so nonspecific as an immunostain when it is so specific as a laboratory test is unclear.

Conclusion

HCG has been shown to be a useful laboratory test for detecting carcinoma in serous effusions, but is not clinically useful as an immunostain in this cytologic context.

References

Fetch PA, Abati A . Immunocytochemistry in effusion cytology: a contemporary review. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 2001;93:293–308.

Osborn M, Wenancjusz D . Special techniques in cytopathology. In Comprehensive Cytopathology, Marluce Bibbo, 2nd edn. Philadelphia WB Saunders, 1996, pp 1058–1060.

Queiroz C, Barral-Netto M, Bacchi CE . Characterizing subpopulations of neoplastic cells in serous effusions: the role of immunocytochemistry. Acta Cytol 2001;45:18–22.

Bedrossian CWM . Special stains, the old and the new: the impact of immunocytochemistry in effusion cytology. Diagn Cytopathol 1998;18:141–149.

Louhimo J, Carpelan-Holmström M, Alfthan H, et al. Serum HCGβ, CA72-4, and CEA are independent prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2002;101:545–548.

Syrigo KN, Fyssas I, Konstandoulakis MM, et al. Beta human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations in serum of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gut 1998;42:88–91.

Boucher LD, Yoneda K . The expression of trophoblastic cell markers by lung carcinomas. Hum Pathol 1995;26:1201–1206.

Lamerz R, Stoetzer OJ, Brandt A, et al. Value of human chorionic gonadotropin compared to CEA in discriminating benign from malignant effusions. Anticancer Res 1999;19:2421–2425.

Pavesi F, Lotzniker M, Cremaschi P, et al. Detection of malignant pleural effusions by tumor marker evaluation. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1988;24:1005–1011.

Zimmerman RL, Goonewardene S, Fogt F . Glucose transporter Glut-1 is of limited value for detecting breast carcinoma in serous effusions. Mod Pathol 2001;14:748–751.

Zimmerman RL, Fogt F, Goonewardene S . Diagnostic value of a second generation CA15-3 antibody to detect adenocarcinoma in body cavity effusions. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 2000;90:230–234.

Zimmerman RL, Fogt F, Goonewardene S . Diagnostic utility of BCA-225 in detecting adenocarcinoma in serous effusions. Analyt Quant Cytol Histol 2000;22:353–357.

de Bruijn HW, ten Hoor KA, Frans M, et al. Rising serum values of beta-subunit human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) in patients with progressive vulvar carcinomas. Br J Cancer 1997;75:1217–1218.

Conelly JH, Johnston DA, Bruner JM . The prognostic value of human chorionic gonadotropin expression in colorectal adenocarcinoms. An immunohistochemical study of 102 stage B2 and C2 nonmucinous adenocarcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993;117:824–826.

Bhalang K, Kafrawy AH, Miles DA . Immunohistochemical study of the expression of human chorionic gonadotropin-β in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 1999;85:757–762.

Carter PG, Iles RK, Neven P, et al. Measurement of urinary beta core fragment of human chorionic gonadotrophin in women with vulvovaginal malignancy and its prognostic significance. Br J Cancer 1995;71:350–353.

Kobata A, Takeuchi M . Structure, pathology and function of the N-linked sugar chains of human chorionic gonadotropin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999;1455:315–326.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmerman, R., Fogt, F. The β subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin lacks specificity for malignant cells in serous effusions. Mod Pathol 17, 701–704 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800086

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800086