Abstract

Primary sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinomas with eosinophilia (SMECE) of the thyroid gland are rare tumors that can present diagnostic difficulties to the pathologist due to the unusual histologic features. Furthermore, the etiology of these tumors has been debated in the literature, with some authors believing that the tumors arise from remnants of the ultimobranchial body (UBB, solid cell nests) and others proposing that they arise from follicular epithelial cells. Because SMECE often occur in glands with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and UBB hyperplasia, and do not stain like follicular or parafollicular cells, it is likely that the tumors do arise from UBB/solid cell nests. In this study, we provide additional evidence for this relationship, by demonstrating that SMECE stain strongly positive for p63, which is a new marker for UBB/solid cell nests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia (SMECE) is a rare tumor of the thyroid gland that has a unique histologic appearance.1 These tumors exhibit a squamoid, nested growth pattern and have a background of dense fibrosis and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis.

The origin of SMECE has been debated in the literature. Two possibilities have been proposed for the etiology of this unusual tumor: malignant transformation of the ultimobranchial body (UBB)/solid cell nests, or malignant transformation of follicular epithelial cells.1, 2, 3 Overall, however, the histologic, epidemiological and immunohistochemical evidence has favored the UBB/solid cell nests as the cell of origin for SMECE.

Recently, a new group of proteins has been identified in the cells of the UBB/solid cell nests that is not present in follicular cells or parafollicular cells (C-cells) of the thyroid gland. This group of proteins is called p63, and represent homologues of p53. Although there are different isoforms, there is a commercially available antibody that detects all isoforms using a common motif. The p63 protein is also expressed in several other cell types, including myoepithelial cells, basal cells (prostate and breast), and in the basal cells of squamous epithelium.4 Because the antibody is relatively new, the immunohistochemical staining pattern for all organs is not entirely clear.

We sought to characterize the staining pattern of the p63 protein product in SMECE of the thyroid. By demonstrating the presence of p63 in SMECE, we have solidified the link between UBB/solid cell nests and this unusual malignant tumor.

Materials and methods

Cases were selected from the files of the Divisions of Anatomic Pathology of the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Pennsylvania, and the personal consultation file of one of the authors (VAL). Cases with the diagnosis of SMECE of the thyroid were included. In addition, 10 cases with normal and hyperplastic ultimobranchial body rests in normal thyroids and those with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, and two cases of papillary carcinoma with squamoid differentiation were also stained with p63. The hematoxylin & eosin (H&E)-stained slides and all immunohistochemically stained slides were examined and the diagnosis was confirmed.

Blank slides were prepared on standard charged slides for immunohistochemical analysis. A streptavadin–biotin with DAB chromagen technique was used, on a Ventana automated immunostainer machine (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA). Briefly, the slides were deparaffinized and then antigen retrieval was performed in a Tris-EDTA buffer at pH 8.5 in a pressure cooker. The antibody used for p63 was obtained commercially from Neomarkers (Fremont, CA, USA) and was used at a 1:200 dilution. A positive control was performed using tissue from the prostate, in which p63 is known to stain the basal cells. A negative control was also prepared, by omitting the primary antibody and following an identical staining procedure.

The immunohistochemically stained slides were examined in the tumor and in normal follicular epithelial cells. Only cells with nuclear positivity were scored as positive. The staining intensity was scored on a scale of 0 (no staining) to 4+ (intense brown color). The percentage of tumor cells staining positive was estimated.

Results

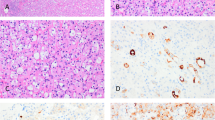

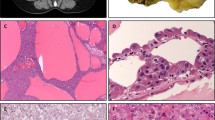

Three cases of sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid were included in this study including two women (aged 37 and 57 years) and one man (aged 64 years). Histologically, all tumors demonstrated squamoid differentiation (Figure 1a), with nests and islands of cells arising in a background of dense fibrosis (Figure 1b). All cases had accompanying lymphocytic thyroiditis with follicular atrophy. Rare tumor cells with mucinous differentiation were present in all cases (Mucicarmine positive).

(a) This photomicrograph demonstrates the nested epidermoid cells of SMECE that are showing focal keratinization (arrowheads). In between the nests of cells, there is a dense infiltrate of eosinophils. (H&E, × 20, original magnification). (b) This photomicrograph demonstrates the background fibrosis that is prominent in SMECE (*). There are strands and nests of epidermoid cells that are infiltrating through the dense fibrosis. (H&E, × 20, original magnification). (c, d) These photomicrographs demonstrates the p63 staining in two of the cases studied (arrowheads). (p63, × 10, original magnification). (e) This photomicrograph shows the positive staining with p63 in the tumor (arrowhead) and negatively staining adjacent atrophic non-neoplastic thyroid follicles (arrows). (p63, × 10, original magnification).

All three cases of SMECE demonstrated intense (4+) nuclear staining of nearly 100% of the tumor cells (Figure 1c–e). The normal adjacent thyroid follicular epithelium did not show any nuclear staining with the p63 antibody (Figure 1e). Positive and negative controls were adequate.

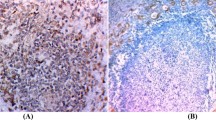

In all cases of non-neoplastic ultimobranchial body rests (normal and hyperplastic in chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis), the UBBs stained positive for p63, and the surrounding thyroid follicular epithelium was negative. In the two papillary carcinomas that had squamoid differentiation, there was no appreciable staining for p63.

Discussion

Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia of the thyroid gland is an extremely rare tumor.5 SMECE shows unique histologic features.1 The tumors have squamoid islands of cells that arise in a fibrotic background. There is usually some degree of mucinous differentiation, although it can be relatively subtle and there may be frank squamous differentiation with keratinization. The surrounding thyroid gland will often have chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis.

SMECE are known to show histologic features that can be confused with several other tumors in the differential diagnosis, including squamous cell carcinoma (primary or metastatic), papillary carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma, and even carcinoma with thymus-like differentiation. Usually, the common histologic features and the characteristic staining profiles of these other tumors will enable the pathologist to arrive at the correct diagnosis, but immunostains can also be helpful (Table 1). SMECE characteristically stain positive for cytokeratins and negative for thyroglobulin and calcitonin.1, 6

The histogenesis of SMECE tumor has been debated in the literature. Because of its characteristic staining profile and its association with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, many authors have proposed that these tumors arise from ultimobranchial body remnants (UBB), also known as solid cell nests, in the thyroid gland.1 However, other authors have suggested that SMECE might arise directly from the follicular epithelial cells, citing rare reports of coexisting papillary carcinoma and SMECE.2, 3

A recent report has further characterized the staining pattern of UBB/solid cell nests. Of particular interest was the finding that the UBBs were positive for p63, which is a p53 homologue protein product.7 We confirmed these results in an additional 10 cases of thyroids with either normal or hyperplastic UBBs. The gene for p63, which is located on chromosome 3q27, is known to harbor germline mutations in rare ectodermal dysplasia syndromes.4, 8 Additionally, p63 knockout mice show extensive epithelial defects in many different organ systems, including skin, prostate, breast, urinary, and gastrointestinal.9 Therefore, the p63 gene expression is thought to play an important role in differentiation of ectodermally derived tissues.10, 11

p63 actually consists of a group of six different isoforms with a common core domain that are all detected by the typically used nonspecific monoclonal antibody that is commercially available.7 The p63 group of proteins is expressed in some ectodermally derived mature normal and some tumor-specific tissues in humans, as detected by immunohistochemical staining. For example, p63 protein has been shown to be highly expressed in basal cells of squamous epithelium, and in the myoepithelial cells of the salivary gland and breast, and basal cells in prostate tissue.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Stromal cells do not appear to express p63.7 Because of the pattern of expression in basal cells, p63 has been proposed to be a marker for stem cells or reserve cells.4

Given the hypothesis that SMECE arises from embryologic remnants of the UBB/solid cell nests, we sought to further establish this pathogenetic link by illustrating the p63 staining pattern in SMECE. In the three cases that we studied, all demonstrated intense nuclear staining in nearly 100% of the tumors cells. Furthermore, this study confirms the presence of p63 staining in normal and hyperplastic UBB/solid cell nests. This marker did not demonstrate positive staining in papillary carcinomas with squamoid differentiation.

The normal follicular epithelial cells did not show nuclear positivity for this marker. The presence of different isotypes for p63 proteins makes it difficult to assess the functional and developmental significance of expression of p63 protein product in mature tissues or stem cells of different organ systems. The nonspecific antibody that we used does not allow us to differentiate between the isotypes. However, with positive immunostaining for p63 protein products in SMECE, it is highly likely that the embryologic origin is ectodermal. It is unlikely that p63 alone will enable distinction between SMECE and the common or rare tumors in the differential diagnosis. For example, typical head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, which can secondarily involve the thyroid, is nearly always positive for p63.13 In the two cases of papillary carcinoma with squamoid differentiation that we examined, the p63 was negative.

The presence of p63 protein in SMECE and non-neoplastic UBB is additional evidence that the two entities are linked biologically and that p63 may serve as a very useful marker for this rare, but challenging tumor in the thyroid gland. By using the histologic findings, histochemical stains for mucin, and a panel of appropriate immunohistochemical stains (p63, thyroglobulin, cytokeratins, calcitonin, and thyroid transcription factor-1), the diagnosis is likely to be established for both common and unusual tumors.

References

Baloch ZW, Solomon AC, LiVolsi VA . Primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma and sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia of the thyroid gland: a report of nine cases. Mod Pathol 2000;13:802–807.

Viciana MJ, Galera-Davidson H, Martin-Lacave I, et al. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid with mucoepidermoid differentiation. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120:397–398.

Arezzo A, Patetta R, Ceppa P, et al. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the thyroid gland arising from a papillary epithelial neoplasm. Am Surgeon 1998;64:307–311.

Reis-Filho JS, Schmitt FC . Taking advantage of basic research: p63 is a reliable myoepithelial and stem cell marker. Adv Anat Pathol 2002;9:280–289.

Sim SJ, Ro JY, Ordonez NG, et al. Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia of the thyroid: report of two patients, one with distant metastasis, and review of the literature. Hum Pathol 1997;28:1091–1096.

Reis-Filho JS, Preto A, Soares P, et al. p63 expression in solid cell nests of the thyroid: further evidence for a stem cell origin. Mod Pathol 2003;16:43–48.

Nylander K, Vojtesek B, Nenutil R, et al. Differential expression of p63 isoforms in normal tissues and neoplastic cells. J Pathol 2002;198:417–427.

Celli J, Duijf P, Hamel BC, et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in the p53 homolog p63 are the cause of EEC syndrome. Cell. 1999;99:143–153.

Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 1999;398:714–718.

Yang A, Kaghad M, Wang Y, et al. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27–29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol Cell 1998;2:305–316.

Levrero M, De Laurenzi V, Costanzo A, et al. The p53/p63/p73 family of transcription factors: overlapping and distinct functions. J Cell Sci 2000;113:1661–1670.

Parsa R, Yang A, McKeon F, et al. Association of p63 with proliferative potential in normal and neoplastic human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 1999;113:1099–1105.

Pruneri G, Pignataro L, Manzotti M, et al. p63 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: evidence for a role of TA-p63 down-regulation in tumorigenesis and lack of prognostic implications of p63 immunoreactivity. Lab Invest 2002;82:1327–1334.

Reis-Filho JS, Milanezi F, Amendoeira I, et al. p63 staining of myoepithelial cells in breast fine needle aspirates: a study of its role in differentiating in situ from invasive ductal carcinomas of the breast. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:936–939.

Shah RB, Zhou M, LeBlanc M, et al. Comparison of the basal cell-specific markers, 34betaE12 and p63, in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1161–1168.

Sniezek JC, Matheny KE, Burkey BB, et al. Expression of p63 and 14-3-3sigma in normal and hyperdifferentiated mucosa of the upper aerodigestive tract. Otolaryngol—Head Neck Surg 2002;126:598–601.

Werling RW, Hwang H, Yaziji H, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction of invasive from noninvasive breast lesions: a comparative study of p63 versus calponin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:82–90.

Preto A, Reis-Filho JS, Ricardo S, et al. p63 expression in papillary and anaplastic carcinomas of the thyroid gland: lack of an oncogenetic role in tumorigenesis and progression. Pathol Res Pract 2002;198:449–454.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hunt, J., LiVolsi, V. & Barnes, E. p63 expression in sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinomas with eosinophilia arising in the thyroid. Mod Pathol 17, 526–529 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800021

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800021

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Salivary-Like Tumors of the Thyroid: A Comprehensive Review of Three Rare Carcinomas

Head and Neck Pathology (2021)

-

Activating BRAF mutation in sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia of the thyroid gland: two case reports and review of the literature

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2019)

-

Thyroid sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of a distinct entity

Modern Pathology (2017)

-

Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2006)