Abstract

Study design:

Systematic review.

Objective:

To evaluate effectiveness and adverse effects of botulinum toxin (BTX) for treatment of urinary incontinence (UI) due to detrusor overactivity (DO).

Methods:

Randomized controlled trials published in English before November 2006 were included if they enrolled subjects with UI caused by DO and reported incontinence outcomes.

Results:

Three trials totaling 104 subjects with DO refractory to antimuscarinic treatment were included. Two BTX-A trials enrolled primarily patients with NDO secondary to spinal cord injury (SCI) (93%). BTX-A decreased daily UI episodes compared to placebo but the reductions were only significantly different at a few of the time intervals during 24 weeks of follow-up. BTX-A was superior in reducing daily UI episodes in SCI subjects compared to intravesical resiniferatoxin at 12 and 18 months after injections. A small crossover study found BTX-B significantly more effective than placebo in reducing weekly UI episodes in subjects with predominately idiopathic DO. Adverse events (AEs) in BTX-A-treated subjects included urinary tract infection, pain at the injection site, hematuria and autonomic dysreflexia. Four subjects treated with BTX-B reported autonomic AEs.

Conclusions:

BTX may improve UI for subjects with refractory DO. The preferred dose and type of BTX is not known. Long-term efficacy and safety remain unclear and require conduct of larger RCT using standardized and validated clinical outcomes measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a frequent problem adversely affecting quality of life in subjects with detrusor overactivity (DO). DO, involuntary contractions of the bladder detrusor muscle during the filling phase, may be neurogenic or idiopathic. Neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO) is often secondary to neurological disorders such as traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) or multiple sclerosis.1 Antimuscarinic drugs (eg, oxybutynin, tolterodine) are commonly used to treat UI due to DO.2 Vanilloid compounds such as capsaicin and resiniferatoxin (RTX) have been assessed in NDO patients refractory to antimuscarinic treatment.3, 4, 5

Preliminary non-randomized studies have recently investigated botulinum toxin (BTX) injected into the detrusor muscle as an agent to treat NDO.6, 7 BTX is a naturally occurring potent neurotoxin produced by Clostridium botulinum bacterium. BTX type A has been used successfully to treat spasmodic or dystonic neuromuscular diseases including cerebral palsy, hemifacial spasm, blepharospasm and cervical dystonia by inhibiting acetylcholine mediated muscle contraction and symptomatic spasm.8 Additional research has also found an antinociceptive effect that is independent of the neuromuscular junction-blocking action indicating BTX-A may be applied for reducing pain or discomfort.9 BTX is thought to improve UI by inhibiting parasympathetic neural transmission into the detrusor muscle in patients with NDO producing temporary paresis.7 Our goal was to conduct a systematic review of evidence from randomized trials to evaluate effectiveness and safety of BTX for treatment for UI caused by neurogenic or idiopathic DO.

Methods

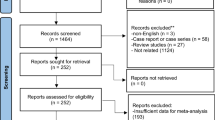

Literature search strategy

A MEDLINE search from 1966 to October 2006 combined an optimally sensitive Cochrane Collaboration search strategy with the MeSH headings ‘urinary incontinence’, ‘botulinum toxins’, ‘botulinum toxin type A’, ‘botulinum toxin type B’, including all subheadings.10 In addition, the Cochrane Library and the Cochrane Urinary Incontinence Review Group specialized registry, and reference lists of identified trials and reviews were searched. Studies were restricted to English language.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they enrolled subjects with UI caused by DO; reported clinical outcomes (eg change in frequency of incontinence episodes based on questionnaire or voiding dairy, pad tests, number returning to continence); randomly assigned participants to treatment or control (usual care/no treatment, placebo or active control); and were published in English.

Data extraction and study appraisal

Study and demographic characteristics, enrollment criteria, efficacy outcomes, quality of life data, adverse effects, number and reasons for dropout were then extracted.

Methodological study quality, the quality of concealment of treatment allocation for randomization, was determined based on the scale developed by Schultz11 (1=poorest quality; 2=unclear; and 3=best quality). We also assessed whether subjects, investigators or outcomes assessors were blinded to the treatment, if intention-to-treat analysis was used and the percent lost to follow-up or withdrawn from study protocol.

Data synthesis

If applicable, efficacy data were pooled and analyzed in the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager (RevMan 4.2) software.12 Weighted mean differences, the difference between treatment and control pooled means at end point, along with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for continuous variables. Relative risks and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated for categorical outcomes. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used if there was evidence of heterogeneity between the studies, based on the χ2-test for heterogeneity and the I2 test.13, 14

Results

Description of studies

Three small trials totaling 104 subjects (range 20–59) previously treated unsatisfactorily with antimuscarinics, met inclusion criteria (Table 1). BTX-A was utilized in two trials,15, 16 while BTX-B was studied in one crossover trial.17 Both toxins have unique immunogenicity and interact with different target proteins, indicating that BTX B may be used in patients refractory to BTX A.18 All administered BTX intramuscularly into the detrusor muscle, avoiding the base and trigone regions, under cystoscopic guidance, generally requiring some anesthesia. For BTX-A, 20 or 30 1.0 ml injections containing 10 U each were administered at different sites. Ten injections at different sites totaling 5000 U were administered for BTX-B. All studies required subject use of (or willing to use) clean intermittent self-catheterization (CIC). BTX was compared to placebo in two studies,15, 17 and to instilled intravesically RTX in one trial.17 Quality of concealment of treatment allocation for randomization was adequate in two trials16, 17 and analysis by intent-to-treat was used for all studies. The placebo-controlled studies were double-blinded.15, 17 Mean study duration was 38 weeks (range 12–78).

Demographic and baseline characteristics of studies

A total of 104 subjects with mainly NDO (84%) were randomized. Mean age was 42 years (range 18–80) and 45% were women. Subjects had an average of 2–5 incontinent episodes per day at baseline. One trial reported racial data and nearly all were white.15 The two BTX-A trials enrolled mostly subjects with NDO secondary to SCI (93%).15, 16 In the trial enrolling only SCI subjects, 68% had concomitant detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia.16 The BTX-B trial randomized predominately idiopathic (85%) DO patients.17 Mean duration of neurologic illness or NDO was approximately 57 months.15, 16

Neurogenic DO primarily related to SCI

In one trial, enrolling 59 mostly SCI subjects (90%), two doses of BTX-A, 200 and 300 U were compared to placebo over 24 weeks.15 All subjects received a single intradetrusor treatment. Statistically significant decreases in UI episodes favored BTX-A 300 U compared to placebo only at weeks 2 and 6 but at no time point beyond (Table 2). BTX-A 200 was significantly superior to placebo only at the end of the 24-week trial. There were statistically significant reductions in UI episodes from baseline for both BTX regimens but not placebo. In secondary analysis, 63% (10 of 300 U and 14 of 200 U) of subjects treated with BTX-A reported no incontinence episodes for at least a single, 1-week period following treatment, versus 24% (5) for placebo (P<0.05). Substantial improvements in the Incontinence-quality of life (IQOL) total scores were reported at all time points in the BTX-A-treated subjects compared with placebo (P⩽0.002). IQOL scores improved for both BTX-A doses (but not placebo) from approximately 45 at baseline to 70 by week 2. Mean differences versus placebo were at least 20 points at week 2 and maintained throughout the 24-week study. There were significant differences between placebo and BTX-A in the urodynamic assessments (maximum cystometric capacity, reflux detrusor volume and maximum detrusor pressure during bladder contraction). No adverse events (AEs) were considered related to the study treatments (Table 3). AEs occurring in more than one subject (combined treatment versus placebo) were urinary tract infections (UTIs), hematuria and pain at the injection site. UTIs were more frequent in the BTX group despite all subjects receiving prophylactic antibiotics. No cases of autonomic dysreflexia were reported and no antibodies to BTX were detected.

In the second BTX-A trial, intramuscularly injected BTX-A 300 U was compared to intravesically instilled RTX 0.6 μM, in 25 subjects with SCI.16 Subjects had the greatest severity of UI among the three included RCTs as measured by daily UI episodes (approximately 5 UI episodes per day). Mean number and mean time between consecutive treatments per patient were 2.1 and 6.8 months for BTX patients and 8.6 months and 51.6 days for RTX patients. BTX-A was significantly superior in reducing (P<0.05) daily UI episodes compared to RTX at 12 and 18 months after injections (Table 2). Both treatments effectively reduced daily incontinence episodes from baseline. There was no statistically significant difference in bladder capacity, uninhibited detrusor contraction threshold or maximum pressure of contractions between RTX and BTX-A. No local AEs were reported for BTX or RTX and antibodies to BTX were not detected. Episodes of autonomic dysreflexia resolved during urodynamics in four and three BTX and RTX subjects, respectively, and no subject reported an episode during everyday life.

Mixed, predominately idiopathic, DO

One small, placebo-controlled crossover trial (N=20) evaluated BTX-B in subjects with predominately idiopathic DO.17 Seventeen subjects had DO of non-neurogenic origin. Ten subjects were randomized to receive BTX-B 5000 international units (IU) and 10 to placebo, crossing over after 6 weeks without a washout period. Short-term, there was a significant improvement in UI episodes with BTX-B treatment compared to placebo. Statistically significant improvements were observed in 5 of the nine domains, including impact on life (domain 2), incontinence impact (domain 3) and incontinence severity (domain 9) of the King's Health Questionnaire of quality of life. Among BTX-B subjects, urinary retention led to the early withdrawal of two subjects and four reported autonomic AEs (constipation, dry mouth, malaise) that were self-limiting (Table 3).

Discussion

The evidence from three small randomized trials suggests that BTX may be an effective and relatively safe treatment option for reducing incontinence and improving incontinence related quality of life in patients with neurogenic or idiopathic DO refractory to oral antimuscarinic agents. In mainly SCI patients, BTX-A therapy significantly decreased daily incontinence episodes as early as two weeks compared to placebo. BTX-A-treated subjects were also more likely to report at least one incontinence free week following treatment and had substantially greater improvements in quality of life scores which may represent clinically significant improvement. Compared to RTX, BTX-A was more effective longer term, with significant differences in the frequency of daily UI episodes at 12 and 18 months. In addition, BTX-treated subjects required fewer treatments on average and with longer intervals between treatments than those treated with RTX. BTX-B improved UI and quality of life in one small study of 20 predominately idiopathic (85%) DO subjects. However, it is unclear whether the statistically significant improvements in several of the quality of life domains represent clinically meaningful improvement. Our findings are consistent with results of BTX in treating UI observed in non-randomized studies in both SCI patients7 and mixed neurogenic and idiopathic DO subjects.19, 20.

AEs in subjects treated with BTX types A and B were generally mild and self-limiting although the safety data from the assessed trials includes only 104 subjects of which 70 were randomized to BTX. Additionally, antibody formation to BTX that could result in tolerance or reaction was not detected. One trial reported nearly twice as many UTIs in the BTX group than in the placebo group although all subjects receiving prophylactic antibiotics.15 Of the four total subjects withdrawing prematurely, one was attributable to an AE on the day of treatment. Two subjects treated with BTX-B developed urinary retention requiring catheterization and did not complete the study.17 The BTX trials had few of the anticholinergic AEs (dry mouth, constipation, dyspepsia, blurred vision) associated with antimuscarinics which can limit dosage, interfere with compliance or lead to withdrawal from treatment.2

The trials, while small, appeared to be relatively well designed and of good quality. Data were analyzed by intention-to-treat in all studies and concealment of treatment allocation for randomization was adequate for two of the trials. However, the BTX-B crossover trial study design presents some concerns. The study did not have a washout period and some treatment effects may have been carried forward.17 Despite the inability to blind to treatment in the BTX vs. RTX trial, no indication that the outcome assessor was blinded to group assignment was noted.16

The need to perform CIC in some individuals will be a limiting factor for the use of BTX-A. Trial results indicate it is unclear whether use of BTX-A can significantly reduce the frequency of CIC following treatment. One trial found a significant reduction of daily catheterizations from baseline16 and the other found catheterization frequency constant throughout the study.15 One non-randomized study of mixed neurogenic and idiopathic DO subjects found most of the patients were unable to void without use of CIC, even in those without significant postvoid residual urine volumes.20 Another non-randomized study noted subjects with DO and inadequate contractility may be at risk for increased postvoid residual urine volumes and the subsequent need for CIC.19 Further studies are needed to determine the optimum ways to administer BTX that would reduce CIC.

Long-term durability, effectiveness and safety of intramuscularly injected BTX are unclear because the trials were short-term study in duration, only ranging from 12 weeks up to 18 months. In the study with the longest follow-up, patients treated with BTX-A received an average of two treatments with a mean time of 7 months between two consecutive injections.16 Although not observed in this trial or reported in other studies, repeated treatments could lead to an increase in drug tolerance,21 drug resistance or antibody formation.18 Administration of BTX is also more difficult than RTX and episodes of autonomic dysreflexia associated with the procedure may occur among SCI patients. BTX application requires either sedation or anesthesia for the patient and a physician skilled with cystoscopy to ensure properly placed injections.16 BTX-B effectiveness may be shorter than BTX-A which would limit its role given the expense and difficulty of administration.

Long-term treatment effects regarding cost and increase of incidence of AEs should also be considered. The cost of treatment is considerable, particularly if the procedure is repeated multiple times. The average cost of BTX-A 300 U ranges from $1100 (200 U) to $1650 (300 U)22 excluding the cost of the cystoscopic application and anesthesia if required.20 None of the included trials reported severe AEs although there are risks associated with sedation and anesthesia. Additionally, weakness, including upper extremity weakness persisting for 90 days in SCI patients, has been reported in case series.23, 24

Conclusions

Intravescial BTX-A may be a relatively safe treatment that provides at least temporary improvement in UI for subjects with NDO refractory to antimuscarinic treatment. BTX-A improved UI outcomes more than placebo although improvement was not statistically significant at all time points. Long term, BTX was more effective than RTX in SCI patients. Additional, large randomized studies are needed to investigate the long-term use of BTX-A. BTX-B was more effective than placebo in improving incontinence in one small short-term study of predominately idiopathic DO subjects. Its effectiveness in treating overactive bladder in the general population and its long-term use remain unclear. A well-designed, long-term, adequately powered study enrolling subjects with non-neurogenic overactive bladder should be initiated to evaluated effectiveness in this population.

References

Jackson S . The patient with an overactive bladder – symptoms and quality-of-life issues. Urology 1997; 50: 18–22.

Chapple C, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Dooley JA . The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2005; 48: 5–26.

de Seze M, Wiart L, Joseph PA, Dosque JP, Mazaux JM, Barat M . Capsaicin and neurogenic detrusor hyperreflexia: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in 20 patients with spinal cord lesions. Neurourol Urodyn 1998; 17: 513–523.

Giannantoni A et al. Intravesical capsaicin versus resiniferatoxin in patients with detrusor hyperreflexia: a prospective randomized study. J Urol 2002; 167: 1710–1714.

Kim JH et al. Intravesical resiniferatoxin for refractory detrusor hyperreflexia: a multicenter, blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Spinal Cord Med 2003; 26: 358–363.

Reitz A et al. European experience of 200 cases treated with botulinum-A toxin injections into the detrusor muscle for urinary incontinence due to neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Eur Urol 2004; 45: 510–515.

Schurch B, Stohrer M, Kramer G, Schmid DM, Gaul G, Hauri D . Botulinum-A toxin for treating detrusor hyperreflexia in spinal cord injured patients: a new alternative to anticholinergic drugs? Preliminary results. J Urol 2000; 164: 692–697.

Hallett M . One man's poison – clinical applications of botulinum toxin. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 118–120.

Sheean G . Botulinum toxin for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain and spasm. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2002; 6: 460–469.

Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C . Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994; 309: 1286–1291.

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG . Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995; 273: 408–412.

Review Manager. [Computer program]: Version 4.1 for Windows. The Cochrane Collaboration: Oxford, England 2001.

DerSimonian R, Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560.

Schurch B et al. Botulinum toxin type A is a safe and effective treatment for neurogenic urinary incontinence: results of a single treatment, randomized, placebo controlled 6-month study. J Urol 2005; 174: 196–200.

Giannantoni A, Di Stasi SM, Stephen RL, Bini V, Costantini E, Porena M . Intravesical resiniferatoxin versus botulinum-A toxin injections for neurogenic detrusor overactivity: a prospective randomized study. J Urol 2004; 172: 240–243.

Ghei M et al. Effects of botulinum toxin B on refractory detrusor overactivity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover trial. J Urol 2005; 174: 1873–1877.

Reitz A, Schurch B . Botulinum toxin type B injection for management of type A resistant neurogenic detrusor overactivity. J Urol 2004; 171: 804–805.

Kuo HC . Urodynamic evidence of effectiveness of botulinum A toxin injection in treatment of detrusor overactivity refractory to anticholinergic agents. Urology 2004; 63: 868–872.

Kessler TM, Danuser H, Schumacher M, Studer UE, Burkhard FC . Botulinum A toxin injections into the detrusor: an effective treatment in idiopathic and neurogenic detrusor overactivity? Neurourol Urodyn 2005; 24: 231–236.

Leippold T, Reitz A, Schurch B . Botulinum toxin as a new therapy option for voiding disorders: current state of the art. Eur Urol 2003; 44: 165–174.

www.drugstore.com (August 2006).

Del Popolo G . Botulinum toxin A in the treatment of detrusor hyperreflexia. Neurourol Urodyn 2001; 20: 522–524.

Wyndaele JJ, Van Dromme SA . Muscular weakness as side effect of botulinum toxin injection for neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 599–600.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Indulis Rutks for his work on literature search and article retrieval. This project was supported by NIDDK R01 DK063300-01A2 the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service and the Minneapolis VA Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. This project was supported by the NIDDK (R01 DK063300-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service, and the Minneapolis VA Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacDonald, R., Fink, H., Huckabay, C. et al. Botulinum toxin for treatment of urinary incontinence due to detrusor overactivity: a systematic review of effectiveness and adverse effects. Spinal Cord 45, 535–541 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102070

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102070

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Current and potential urological applications of botulinum toxin A

Nature Reviews Urology (2015)

-

Prevention of recurrent autonomic dysreflexia: a survey of current practice

Clinical Autonomic Research (2015)

-

Functional electrical stimulation for management of urinary incontinence in children with myelomeningocele: a randomized trial

Pediatric Surgery International (2014)

-

Intérêt et résultats de l’utilisation de la toxine botulique dans l’hyperactivité détrusorienne d’origine neurologique

Pelvi-périnéologie (2009)