Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objective:

To describe a case of pediatric calcified intervertebral disc herniations at the cervical–thoracic junction surgically treated with laminoplasty.

Methods:

A 13-year-old girl with calcified intervertebral disc herniations at C7/Th1 and Th1/2 causing myelopathy was performed with laminoplasty .

Results:

Postoperative course was without complication, and the neurologic examination returned to a completely normal state at 5 years to date after surgery.

Conclusions:

Laminoplasty produced an excellent result and is a consideration for treatment of similar cases of calcified intervertebral disc herniation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcified intervertebral disc herniation in children is rare and its etiology is unknown. The majority of such cases are treated conservatively since spontaneous resorption of the calcified lesion can be expected, and neurologic abnormalities such as radiculopathy and myelopathy are unusual. Surgical treatment is indicated for significant neurologic problems. We present a case with a calcified nucleus pulposus, which had ruptured into the spinal canal, causing progressive myelopathy. This is the first known report on this disease treated by laminoplasty.

Case report

Clinical presentation

A 13-year-old girl presented with sudden onset of neck and upper back pain 7 weeks before the first visit to our hospital. After 1 month she developed neurologic symptoms and signs of progressive paresis and sensory loss at the Th3 level. She progressively lost her ability to stand or walk. Bilateral deep tendon reflexes of the lower extremities were hyperactive. All chemistry and hematology tests were normal. Although there was no history of infection or trauma, she was taking oral medication for bronchial asthma.

Neuroradiology

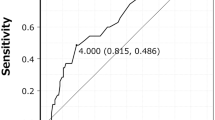

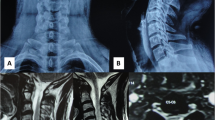

A plain radiograph of the lateral cervical spine demonstrated inability to see the C7/Th1 disc level (Figure 1). T2-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI) revealed a marked compression of the dural sac and spinal cord due to a large extradural mass of very low signal intensity at the C7/Th1 level (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) revealed calcifications in the intervertebral discs and posterior herniation by the calcified discs into the spinal canal from C7/Th1 to Th1/2 (Figure 3).

Surgical management and postoperative course

An expansive laminoplasty from C5 to Th2 was performed 7 weeks following presentation to manage the progressive neurologic deterioration. The procedure according to Kurokawa et al1 was used (ie, enlargement in the spinal canal by sagittal splitting of the spinous process). The calcified portion of the intervertebral discs and the displaced disc lesion was not removed. The postoperative course was without complication, and she was able to walk within 1 month after surgery.

At 5 years to date after the surgery, she has remained symptom free and she had a completely normal neurologic examination. MRI obtained at 5 years after surgery has confirmed mild compression on the dural sac, but no compression on the spinal cord at the C7/Th1 level (Figure 4). CT scan revealed that the old calcifications on the nucleus pulposus at C7/Th1 and Th1/2 level still remained 5 years after surgery. The calcification of the spinal canal was much diminished at C7/Th1, and had disappeared at Th1/2 (Figure 5).

Discussion

Pediatric intervertebral disc calcification was first reported in a 12-year-old boy by Báron in 1924.2 Since then, more than 227 cases have been reported.3 Pediatric intervertebral disc calcification is more common in boys than in girls. The peak incidence has been from 6 to 10 years of age (mean age, 8 years).4, 5, 6, 7 Radiographic evidence of disc protrusion has been reported in approximately 38% of all cases of symptomatic pediatric intervertebral disc calcification.6 In rare cases, rupture in the annulus may occur, with radicular pain or neurologic deterioration.4, 5, 6, 7

The etiology of this entity is not clear, although a mild upper respiratory tract infection or injury may be associated.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Theories explaining the symptoms associated with disc calcification in children include an elevated hydrostatic pressure within the disc, nutritional disturbances in the nucleus pulposus arising from vascular impairment, inflammation of the disc, and protrusion of the intervertebral disc into the spinal canal.9

Plain radiographs are often normal in this disease. Most calcified intervertebral disc herniations are located in the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine, the most common site being at C6/7.6 On plain radiographs, the calcification may be difficult to identify at the cervical–thoracic junction because of the shoulders, so tomography, CT and/or MRI may be necessary.

Intervertebral disc calcification is usually a self-limited process. The majority of patients are symptomatic only, with a normal neurologic examination. In most cases, the calcification disappears spontaneously within a few weeks to months, although in a few cases it may persist.3, 4, 5, 6, 8 In our case with myelopathy, the calcification persisted even after 5 years, although she was otherwise symptom free after laminoplasty.

In general, conservative treatment is recommended, and the prognosis is excellent even when herniation of the nucleus pulposus occurs.4, 5, 10 Surgical treatment is required in patients who develop progressive neurologic deterioration. In rare cases of spinal cord and/or nerve root compression by herniation of the calcified disc, it has been reported that operative removal of the disc is indicated.4, 5, 8, 11, 12 Anterior cervical discectomy with or without fusion has been reported in the literature only in a few cases.4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13 All patients became asymptomatic after the displaced disc lesion was removed. Peck14 and MacCartee15 have reported cases of thoracic calcified nucleus pulposus that had ruptured into the spinal canal, causing signs of cord compression, relieved by laminectomy. Although laminoplasty for similar types of cord compression without the calcification has been reported,16, 17, 18 there has been no report to date on this disease at the cervical–thoracic junction treated by this method.

Surgical treatment is necessary for patients in whom there is evidence of progressive cord compression with neurologic deterioration. The main objective of surgical treatment is decompression of spinal cord and/or nerve root, and is not resection of the calcified lesion. Laminectomy will effectively decompress the spinal cord, but progressive kyphotic deformity and cervical instability are common in children after laminectomy.19, 20, 21 In addition, the surgical scar on the posterior neck has generally gone unnoticed because it can easily be covered with hair. If progressive neurological deterioration occurs, laminoplasty with decompression of the spinal cord should be considered in patients with calcified intervertebral disc herniation.

References

Kurokawa T et al. Enlargement of spinal canal by sagittal splitting of spinal process. Bessatsu Seikeigeka 1982; 2: 234–240 (in Japanese).

Báron A . Über eine neue Erkrankung der Wirbelsäule. Jahrb Kinderh 1924; 104: 357–360.

Ventura N et al. Intervertebral disc calcification in childhood. Int Orthop 1995; 19: 291–294.

Smith RA et al. Calcified cervical intervertebral discs in childen: report of three cases. J Neurosurg 1977; 46: 233–238.

Mohanty S, Sutter B, Mokry M, Ascher PW . Herniation of calcified cervical intervertebral disk in childen. Surg Neurol 1992; 38: 407–410.

Sonnabend DH, Taylor TK, Chapman GK . Intervertebral disc calcification syndromes in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 64-B: 25–31.

Swick HM . Calcification of intervertebral discs in childhood. J Pediatr 1975; 86: 364–369.

Gerlach R et al. Intervertebral disc calcification in childhood – a case report and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir 2001; 143: 89–93.

Heinrich SD et al. Calcific cervical intervertebral disc herniation in childen. Spine 1991; 16: 228–231.

Mainzer F . Herniation of the nucleus pulposus. A rare complication of intervertebral-disk calcification in children. Pediatr Radiol 1973; 107: 167–170.

Oga M et al. Herniation of calcified cervical intervertebral disc causes dissociated motor loss in a child. Spine 1993; 18: 2347–2350.

Schaser KD et al. Mild cervical spine trauma showing symptomatic calcified cervical disc herniation in a child: a case report. Spine 2003; 28: E93–E94.

Coventry MB . Calcification in a cervical disc with anterior protrusion and dysphagia. J Bone Joint Surg 1970; 52-A: 1463–1466.

Peck FC . A calcified thoracic intervertebral disk with herniation and spinal cord compression in a child: case report. J Neurosurg 1957; 14: 105–109.

MacCartee CC, Griffin PP, Byrd EB . Ruptured calcified thoracic disc in a child. J Bone Joint Surg 1972; 54-A: 1272–1274.

Fujimoto Y et al. Pathophysiology and treatment for cervical flexion myelopathy. Eur Spine J 2002; 11: 276–285.

Yoshida M et al. Indication and clinical results of laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy caused by disc herniation with developmental canal stenosis. Spine 1998; 23: 2391–2397.

Yue WM et al. Results of cervical laminoplasty and a comparison between single and double trap-door techniques. J Spinal Disord 2000; 13: 329–335.

Cattell H, Clark Jr GL . Cervical kyphosis and instability following multiple laminectomies in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1967; 49-A: 713–720.

Yasuoka S et al. Pathogenesis and prophylaxis of postlaminectomy deformity of the spine after multiple level laminectomy: difference between children and adults. Neurosurgery 1981; 9: 145–152.

Yasuoka S, Peterson HA, MacCarty CS . Incidence of spinal column deformity after multilevel laminectomy in children and adults. J Neurosurg 1982; 57: 441–445.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, K., Nagata, K. & Park, J. Calcified intervertebral disc herniation in a child with myelopathy treated with laminoplasty. Spinal Cord 43, 680–683 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101755

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101755

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Is conservative treatment a good choice for pediatric intervertebral disc calcification in children?

European Spine Journal (2022)

-

Histologically proven acute paediatric thoracic disc herniation causing paraparesis: a case report and review of literature

Child's Nervous System (2015)

-

Ernia calcifica di nucleo polposo in età pediatrica

Archivio di Ortopedia e Reumatologia (2010)