Abstract

This double-blind study investigated the efficacy and safety of rapid-acting intramuscular olanzapine in treating agitation associated with Alzheimer's disease and/or vascular dementia. At 2 h, olanzapine (5.0 mg, 2.5 mg) and lorazepam (1.0 mg) showed significant improvement over placebo on the PANSS Excited Component (PANSS-EC) and Agitation–Calmness Evaluation Scale (ACES), and both 5.0 mg olanzapine and lorazepam showed superiority to placebo on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. At 24 h, both olanzapine groups maintained superiority over placebo on the PANSS-EC; lorazepam did not. Olanzapine (5.0 mg) and lorazepam improved ACES scores more than placebo. Simpson–Angus and Mini-Mental State Examination scores did not change significantly from baseline. Sedation (ACES ⩾8), adverse events, and laboratory analytes were not significantly different from placebo for any treatment. No significant differences among treatment groups were seen in extrapyramidal symptoms or in corrected QT interval at either 2 h or 24 h, and no significant differences among treatment groups were seen in vital signs, including orthostasis. Intramuscular injection of olanzapine may therefore provide substantial benefit in rapidly treating inpatients with acute dementia-related agitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It has been estimated that 5% of people older than 65, and up to 20% of those aged 80 and older, are affected by dementia (Gurland and Cross 1982; Small and Jarvik 1982). Of these, nearly half exhibit behavioral disturbances, such as agitation, wandering, and violent outbursts (Kunik et al. 1994). Agitation has been defined as “inappropriate verbal, vocal, or motor activity not explainable by apparent needs or confusion” (Cohen-Mansfield 1986), and includes both physically and verbally aggressive behaviors such as hitting, biting, and screaming, and nonaggressive behaviors such as pacing, wandering, and continual requests for attention. In nursing home patients with dementia, the prevalence of these disturbances may be as high as 75% (Deutsch and Rovner 1991).

Severe symptoms of agitation may require rapid treatment in the form of parenteral medication when a very rapid onset is required or when patients refuse or cannot take oral agents. In some instances, the use of medication is less desirable than alternative methods such as behavioral intervention. However, occasions arise where a pharmacological intervention is unavoidable and in the best interests of the patient. Lorazepam is commonly used for treatment of acute agitation, and the benzodiazepines are currently among the few agents available in a parenteral formulation for treatment of agitation. Use of orally administered atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine and risperidone has met with some success in treating behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia (Clark et al. 2001; De Deyn et al. 1999; Katz et al. 1999; Street et al. 2000). A parenteral formulation of a second-generation antipsychotic might offer some advantage over their corresponding oral formulations due to faster onset of effect and utility where the patient cannot, or will not, accept oral treatment (Bianchetti et al. 1980; Schaffer et al. 1982). Rapid tranquilization with parenteral typical antipsychotic agents may induce hypotension (Marsden and Jenner 1980; Schwartz and Brotman 1992), cardiotoxicity (Marsden and Jenner 1980; Schwartz and Brotman 1992), and extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) (Foster et al. 1997; Salzman et al. 1991), all of which are of particular concern in an elderly population because of their enhanced susceptibility to EPS (Caligiuri et al. 1999). Until now, rapidly acting, parenterally administered atypical neuroleptics have been unavailable in the United States.

Olanzapine is an atypical neuroleptic agent that has been approved for oral treatment of both schizophrenia and acute mania. A previous study has shown positive results with the use of a rapidly acting intramuscular formulation of olanzapine in the treatment of agitation associated with psychosis in elderly patients with schizophrenia (Wright et al. 2000). The present study investigates the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injection of olanzapine in the treatment of agitation associated with dementia, testing the hypothesis that olanzapine is more effective than placebo in treating agitation.

METHODS

Study Group

Patients in this study were clinically agitated inpatients, hospitalized or nursing home residents, aged 55 or older, who met either National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke—Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association or DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria for possible or probable Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular dementia, or a combination of both (“mixed dementia”). Patients were initially screened on the basis of chart reviews, staff interviews, and recommendations by the investigators and patients' family members. For study inclusion, patients must have scored ⩾14 on the Excited Component of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al. 1986); for description of Excited Component, see Assessments section), have at least one individual PANSS item score ⩾4 on a scale of 1–7, and be diagnosed with clinically significant agitation for which treatment with a parenteral agent is indicated. Patients were excluded if they received benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, or anticholinergics within 4 h prior to the first injection of study drug, if they received psychostimulants or reserpine within one week prior to study drug administration, or an injectable depot neuroleptic within less than one dosing interval of study initiation, if they had been diagnosed with any serious neurological condition other than AD or vascular dementia that could contribute to psychosis or dementia, if they had laboratory or ECG abnormalities with clinical implications for the patient's participation in the study, or if they were judged to be at serious risk of suicide. Prior to participation, all patients or their designated representatives signed an informed consent document approved by the study site's Institutional Review Board.

Study Design

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel study, conducted at 33 sites in the United States, two in Russia, and three in Romania. Study Period I consisted of a screening period to assess patients' eligibility for enrollment. A screening electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed within 6 h prior to the first injection. If it was not possible to obtain an ECG within 6 h prior to the first injection, an ECG which had been obtained within two weeks prior to the first injection was used as baseline. Study Period II began with initiation of preliminary evaluations for the first injection, and continued for 24 h. Randomization was performed in a 1:1:1:1 ratio between IM olanzapine 2.5 mg (Olz2.5), IM olanzapine 5.0 mg (Olz5.0), IM lorazepam 1.0 mg (Lzp), and IM placebo treatment groups. A second and third injection were optional, administered as needed in the clinical opinion of the investigator, but within 20 h of the first injection. Injections 1 and 2 consisted of olanzapine 2.5 mg, olanzapine 5.0 mg, lorazepam 1.0 mg, or placebo, depending on the patient's assigned treatment group. Injection 2, if deemed clinically necessary, was given at least 2 h after injection 1. The doses of injection 3, if deemed necessary, were as follows: the Olz5.0 group received olanzapine 2.5 mg, the Olz2.5 group received olanzapine 1.25 mg, the Lzp group received lorazepam 0.5 mg, and the placebo group received olanzapine 5.0 mg (“crossover” patients), for a maximum drug exposure of 12.5 mg of olanzapine, 6.25 mg of olanzapine, 2.5 mg of lorazepam, and 5.0 mg of olanzapine, respectively. Injection 3 was given at least 1 h after injection 2. If a patient required treatment with another therapeutic agent for agitation after injection 3, that patient was discontinued from the study.

Assessments

Patients' levels of agitation were assessed prior to the first dose, every 30 min for the first 2 h, and at 4, 6, and 24 h post first injection. Assessment scales included the PANSS Excited Component (PANSS-EC; Kay et al. 1986; Kay and Sevy 1990; Lancon et al. 2000; Lindenmayer et al. 1995; Wolthaus et al. 2000), Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI; Cohen-Mansfield 1986; Cohen-Mansfield et al. 1990), and the Agitation–Calmness Evaluation Scale (ACES). The PANSS-EC subscale consists of five items of the PANSS: poor impulse control, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness, and excitement. The CMAI is a 30-item, 7-point rating scale used to rate the frequency with which patients exhibit agitated behavior. The ACES is a Lilly internally developed scale ranging from 1 = marked agitation to 9 = unarousable. This scale has a high convergent validity and high reliability. The degree of convergent validity was explored by investigating the relationship between the ACES and the PANSS-EC and the CMAI. In both cases, a large and significant correlation was found with the ACES (r = −.71, p = .0001; and r = −.59, p = .0001, respectively). During inter-rater testing, a high degree of reliability was found, with an average concordance of 83.6%. Average concordance within one point was 98.7%.

The a priori primary objective in this study was to assess the efficacy of 5.0-mg IM olanzapine compared with placebo in improving severity of agitation at 2 h post first injection, as measured by reduction from baseline on the PANSS-EC. Additional, secondary measures of agitation at the 2-h timepoint included the CMAI and the ACES. Changes from baseline to 24 h post first injection also served as additional efficacy measures, using the PANSS-EC, the PANSS-derived Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorham 1962) total and positive symptomatology cluster, CMAI, ACES, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al. 1975), and Clinical Global Impression–Severity of Illness scale (CGI-S; Guy 1976) for dementia.

As an additional measure of baseline severity of illness, patients were assessed with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory/Nursing Home version (NPI/NH; Wood et al. 2000). The NPI/NH evaluates psychopathology in patients with AD and other dementias, and is based on responses obtained by a trained interviewer from the primary caregiver who was involved in the ongoing care of the patient in the month prior to the study. The NPI/NH consists of 10 behavioral and 2 neurovegetative items, with the score of each item, if present, representing the product of symptom frequency (1 = occasionally to 4 = very frequently) times severity (1 = mild to 3 = severe). For each item, an Occupational Disruptiveness score is obtained and encompasses the work, effort, time, or distress a particular behavior causes the staff caregiver (0 = no disruption to 5 = very severe or extreme).

At screening, medical history, psychiatric assessment, physical examination, electrocardiographs (ECGs), vital signs, and laboratory profile were obtained. Extrapyramidal symptoms were assessed with the Simpson-Angus Scale. Adverse events were detected by clinical evaluation and spontaneous report throughout the study. To this end, observers and staff were trained to report any physiological or psychological change while maintaining patients under continuous observation. ECGs were recorded at screening and endpoint (both 2 h and 24 h post first injection, and/or upon discontinuation after randomization).

Statistical Methods

Patient data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis (Gillings and Koch 1991). For analysis of last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) mean change from baseline to endpoint, patients with a baseline and at least one postbaseline measurement were included in the analysis. In the change from baseline to 24-h endpoint analyses, endpoint scores for placebo patients were defined as the last observation prior to the third injection. All tests were 2-tailed, with an α level of .05. To determine if olanzapine was more efficacious than placebo, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to the mean change in PANSS-EC scores from baseline to 2 h post first injection. The model initially included terms for treatment, country, and treatment-by-country interaction. Tests of interaction were deemed significant at an α level of .10. If the interaction was deemed nonsignificant, the term was removed from the model, and the between-treatment group p value was obtained from the main effects model. Comparisons among treatment groups were evaluated using contrasts of the least-square means. Continuous data of changes from baseline within treatments were analyzed by Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test. Comparisons between patients in nursing home settings and those in hospital settings were made using Student's t-test.

Response rates were calculated from the PANSS-EC score using an LOCF technique. A responder was defined a priori as any patient who achieved at least a 40% reduction in PANSS-EC score from baseline to endpoint at 2 h post first injection. Response rates and categorical data (demographic variables, reasons for study discontinuation, study drug injection frequency, treatment-emergent adverse events, incidence of concomitant drug use, incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms, and incidence of oversedation) were evaluated using Fisher's exact test. To assess treatment-emergent parkinsonism, the proportion of patients with a Simpson–Angus total score >3 during the 24-h study period was calculated from among those with a total score ⩽3 at baseline. This definition was established a priori and has been used in previous olanzapine studies (Sanger et al. 1999; Tran et al. 1997). Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to response on the PANSS-EC during the 2 h post first injection were compared among treatment groups using a log-rank test.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Disposition

In total, 331 patients entered the screening phase of the study, of whom 272 were randomized to treatment. Among the 59 patients who were not randomized, reasons for nonrandomization included Criteria Not Met (n = 43), Physician Decision (n = 9), Patient Decision (n = 5), and Adverse Event (n = 2). Demographics of the randomized patients did not differ significantly among the four treatment groups. Most patients were Caucasian (92.3%), the majority were female (61.0%), and the average age was 77.6 years (SD = 9.7; range, 54–97). The percentage of patients taking at least one concomitant medication was not significantly different among treatment groups. The percentage of patients completing the 24-h post first injection period and not discontinuing the study was roughly equal among the three active-treatment groups (Olz2.5, 94.4%; Olz5.0, 92.4%; Lzp, 89.7%; placebo, 88.9%). No patients withdrew due to an adverse event, and discontinuations due to lack of efficacy were approximately equal among the treatment groups (Olz2.5, 5.6%; Olz5.0, 3.0%; Lzp, 7.4%; placebo, 2.8%). Of the 31 “crossover” patients who transitioned from placebo to a third injection consisting of 5-mg olanzapine, 25 (80.6%) completed the study, 5 (16.1%) withdrew due to lack of efficacy, and one (3.2%) withdrew due to an adverse event (tachycardia).

The overall mean baseline MMSE score was 11.8 (SD = 7.1), indicating moderate cognitive impairment. Patients from nursing homes were significantly more cognitively impaired than those from hospital inpatient settings (nursing homes: 9.0, SD = 8.6, n = 59; hospitals: 12.6, SD = 6.3, n = 185; t = 2.98, p = .004). Mean BPRS total score (possible range: 0–108) at baseline was 35.8 (SD = 10.4), indicating mild psychiatric illness, with nursing-home patients again showing greater debilitation (nursing homes: 39.0, SD = 9.7, n = 60; hospitals: 34.8, SD = 10.4, n = 203; t = 2.88, p = .005). NPI/NH scores at baseline likewise indicated mild-to-moderate levels of psychotic and depressive/dysphoric symptomatology, and moderate levels of anxiety. Measurements of the caregivers' distress, brought about by patients' psychotic and behavioral symptoms, indicated moderate levels of occupational disruptiveness. Overall mean baseline PANSS-EC score was 19.75 (SD = 13.00), ACES score was 2.18 (SD = 0.71), and CMAI score was 6.97 (SD = 6.00), corresponding to moderate-to-severe levels of agitation. PANSS-EC scores indicated that nursing-home patients were slightly but significantly more agitated than hospitalized patients (nursing homes: 20.9, SD = 4.5, n = 63; hospitals: 19.4, SD = 4.1, n = 209; t = 2.35, p = .02). The treatment groups were comparable at baseline on all measures. Measures of adverse events at baseline indicated that many patients had compromised cardiac health: 41.2% had hypertension, 32.0% had some degree of coronary artery disease, including histories of myocardial infarctions, 12.9% had congestive heart failure, and 12.9% had cerebrovascular and/or peripheral vascular disease. In addition, there were 13.2% with chronic respiratory disease, 11.4% with diabetes, and 13.6% with hypothyroidism.

Significantly more patients in the placebo group (31 of 67, 46.3%) required a third injection than in either olanzapine-treatment group (Olz5.0: 11 of 66, 16.7%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001; Olz2.5: 18 of 71, 25.4%; Fisher's exact test, p = .01) or in the lorazepam-treatment group (14 of 68, 20.6%; Fisher's exact test, p = .002). Differences among the three active-treatment groups were not significant. Conversely, significantly more patients in the Olz5.0 group (42 of 66, 63.6%) required only one injection, compared with the patients in the placebo group (28 of 67, 41.8%; Fisher's exact test, p = .02). However, the number of patients requiring only one injection was not significantly greater than placebo for the Lzp (40 of 68, 58.8%; Fisher's exact test, p = .06) or Olz2.5 (42 of 71, 59.2%; Fisher's exact test, p = .06) groups. Differences among the three active-treatment groups were not significant.

Efficacy Results

Two Hours Post First Injection. At 2 h post first injection, patients in both the Olz5.0 and Lzp treatment groups showed significantly greater improvement relative to placebo on all three measures of agitation, while patients receiving 2.5-mg olanzapine showed significantly greater improvement relative to placebo in their PANSS-EC and ACES scores (Tables 1 and 2 ). Differences among the three active-treatment groups on the three measures of agitation were not significant. Patients in all four treatment groups showed significant improvements from baseline (p < .001) on all three measures of agitation. Mean score on the ACES for Olz2.5 at the 2-h endpoint was 4.07 (4 = normal), 4.05 for Olz5.0, 4.35 for Lzp, and 3.18 (3 = mild agitation) for the placebo group, indicating that patients treated with olanzapine and lorazepam did not experience excessive sedation.

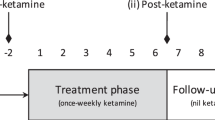

Analysis of variance of the mean PANSS-EC scores within the 2 h post first injection revealed an overall treatment difference that became significant by the 60-min timepoint (F3,266 = 2.73, p = .04). However, differences among the three active-treatment groups, exclusive of the placebo group, were not significant at any timepoint. Olz5.0 was significantly more efficacious than placebo at 30 min postinjection, the first postbaseline timepoint at which the PANSS-EC was administered (Olz5.0: mean −5.09, SD = 5.80, n = 66; placebo: mean −3.29, SD = 5.41, n = 66; F1,265 = 3.86, p = .05; Figure 1 ). This superiority was maintained at all successive timepoints (60, 90, 120 min). Olz2.5 scores showed significantly greater improvement relative to placebo only at the 120-min timepoint (Olz2.5: mean, −7.86, SD = 6.05, n = 71; placebo: mean, −5.27, SD = 6.87, n = 67; F1,266 = 5.14, p = .02), although Olz2.5 showed significant improvement relative to baseline by the first timepoint at 30 min (mean, −4.90, SD = 5.19, n = 71; Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test, p < .001) and at each subsequent timepoint. Improvement with lorazepam became significantly superior to placebo at the 60-min timepoint (Lzp: mean –7.47, SD = 5.59, n = 68; placebo: mean –5.12, SD = 5.76, n = 66; F1,266 = 6.44, p = .01), and this improvement was maintained until the 2-h timepoint. No significant differences were found between patients in nursing-home versus hospital settings on any measures of efficacy.

Visitwise change in PANSS Excited Component score (LOCF) from baseline to 2 h post first injection of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo. Intramuscular administration of olanzapine 5.0 mg was significantly more efficacious than placebo at every post-baseline timepoint (30, 60, 90, 120 min). Olanzapine 2.5 mg was more efficacious than placebo at the 120-min timepoint. Lorazepam 1.0 mg was more efficacious than placebo at 60, 90, and 120 min post first injection. *p ⩽ .05 relative to placebo, analysis of variance.

Clinical response, defined a priori as ⩾40% improvement from baseline in PANSS-EC score, was achieved at 2 h post first injection in 44 of the 66 Olz5.0 patients (66.7%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001 relative to placebo), 44 of the 71 Olz2.5 patients (62.0%; Fisher's exact test, p = .006 relative to placebo), and 49 of the 68 Lzp patients (72.1%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001 relative to placebo), compared with 25 of 67 patients (37.3%) in the placebo group. Differences among the active-treatment groups were not significant.

As an additional post hoc measure of improvement, categorical analyses were conducted based on the incidence rates of the number of patients with at least one PANSS-EC individual item score ⩾4 (at least moderate psychopathology) at baseline and all five item scores <4 (mild-to-none) at the 2-h endpoint. All three active-treatment groups had a significantly higher incidence of improved patients (Olz5.0: 46 of 66, 69.7%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001; Olz2.5: 45 of 71, 63.4%; Fisher's exact test, p = .006; Lzp: 48 of 68, 70.6%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001) at 2 h post first injection than were seen in the placebo group (26 of 67, 38.8%). No significant differences in incidence rates were seen among the active-treatment groups.

Twenty-four Hours Post First Injection. At 24 h post first injection, changes from baseline had lessened for all four treatment groups relative to the 2-h timepoint on all three measures of agitation (Table 2). Changes from baseline on the PANSS-EC were still significantly greater than placebo for the two olanzapine groups (placebo: mean −3.81, SD = 6.20, n = 67; Olz5.0: mean −6.29, SD = 6.75, n = 66, t266 = −2.26, p = .02; Olz2.5: mean −6.44, SD = 6.00, n = 71, t266 = −2.45, p = .02), whereas the change in the lorazepam group was no longer significant (mean –5.75, SD = 5.99, n = 68, t266 = −1.91, p = .06). The improvement seen in ACES scores at 24 h was still significantly greater than placebo (mean 0.63, SD = 1.14, n = 67) in both the Olz5.0 (mean 1.29, SD = 1.49, n = 66, 2-tailed pairwise t266 = 3.04, p = .003) and the Lzp groups (mean 1.07, SD = 1.12, n = 68, t266 = 2.13, p = .03). Improvement in ACES scores for Olz2.5 (mean 0.90, SD = 1.19, n = 71, t266 = 1.26, p = .21) was no longer significantly greater than that for the placebo group, although Olz2.5 still showed significant improvement from baseline (Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test, p < .001). At 24 h, there were no significant differences between placebo and either olanzapine group or lorazepam on the BPRS total, BPRS Positive, CMAI, CGI-S, or MMSE total. Patients in hospital settings had a greater mean improvement in CGI-S scores at 24 h (mean, −0.54; n = 179) than patients in nursing homes (mean, −0.21, n = 58; t214.4 = −3.77, p<.001).

Categorical analyses were again conducted based on the incidence rates among the treatment groups at 24 h post first injection of the number of patients with at least one PANSS-EC individual item score ⩾4 at baseline and all five item scores <4 at endpoint. As at the 2-h timepoint, all three active-treatment groups had higher improvement incidence rates (Olz5.0: 38 of 66, 57.6%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001; Olz2.5: 40 of 71, 56.3%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001; Lzp: 39 of 68, 57.4%; Fisher's exact test, p < .001) than were seen in the placebo group (18 of 67, 26.9%), but no significant differences were seen among the active-treatment groups.

Safety Results

Extrapyramidal symptom scores on the Simpson–Angus Scale were not significantly different among the four treatment groups at baseline, and they did not change significantly from baseline to endpoint. Baseline-to-endpoint changes in the two olanzapine-treatment groups and in the lorazepam-treatment group were not significantly different from those in the placebo group. Overall and within-group categorical differences in the incidence of treatment emergent parkinsonism were not significant.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (Table 3) were not significantly different from placebo in any active-treatment group. MMSE scores, indicative of cognitive state, were not substantially changed from baseline in any treatment group, and no significant differences were seen in mean change scores among the four treatment groups (Table 2). Using the treatment-emergent occurrences of ACES values of 8 (“deep sleep”) or 9 (“unarousable”) as a categorical measure of oversedation, no differences were seen in incidence rates among the olanzapine, lorazepam, and placebo groups at any time, either during the 2-h (Fisher's exact test, p = .84) or 24-h period (Fisher's exact test, p = .81) post first injection. The incidence of the adverse event somnolence was also not significantly different between treatment groups (Table 3), and all instances of somnolence were determined to be moderate or mild.

No statistically or clinically significant overall differences were seen among the treatment groups in any vital sign, including orthostasis, or in any laboratory analyte, including plasma glucose levels. Analysis of electrocardiographic data at 2 h post first injection revealed a significant decrease from baseline in corrected QT interval (QTc) in the Lzp group (−6.18 ms, SD = 20.59, n = 63; Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test, p = .007) which was not seen at 24 h. Similarly, the Olz2.5 group showed a significant decrease relative to baseline in QTc at 24 h (−7.41 ms, SD = 21.80, n = 68; Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test, p = .009), while placebo led to a significant increase in QTc relative to baseline (+5.44 ms, SD = 20.16, n = 64; Wilcoxon's Signed Rank Test, p = .048). In a categorical analysis of QTc, a baseline interval <500 ms followed by a postbaseline interval ⩾500 ms at any time was classified as abnormal (Morganroth et al. 1993). There was no statistically significant overall difference among the treatment groups in the incidence of QTc intervals ⩾500 ms and no statistically significant pairwise comparisons between treatment groups at either 2 h or 24 h. Two patients (3.3%) in the Olz5.0 group, one patient (1.5%) in the Olz2.5 group, three patients (4.7%) in the Lzp group, and three patients (4.8%) in the placebo group exceeded this threshold during the 24-h period. No other potentially clinically significant ECG changes were observed.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of agitation in elderly patients with dementia currently relies on pharmacotherapy with one or more of a variety of different agents, including the benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, and putative mood stabilizers such as β-adrenergic antagonists, carbamazepine, and lithium (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 1990). Of these, the neuroleptics and benzodiazepines are the most frequently prescribed (Devanand and Levy 1995). Benzodiazepines may be most useful for as-needed administration for infrequent agitation or for short-term treatment of agitation accompanied by anxiety (Class et al. 1997). Moreover, the benzodiazepines are associated with a number of risks, such as dependence and tolerance, amnestic effects, high levels of daytime sedation, and respiratory depression. Lorazepam and oxazepam have been the preferred benzodiazepine agents due to their short half-lives and lack of active metabolites (Barclay 1985; Greenblatt and Divoll 1983). Lorazepam, in particular, has been demonstrated to be at least as effective as haloperidol in controlling agitation in psychosis but without the attendant extrapyramidal toxicity of the typical antipsychotics (Salzman 1988; Salzman et al. 1991), to which the elderly are particularly susceptible (Caligiuri et al. 1999). These advantages, along with lorazepam's frequent clinical use, led to the decision to include its IM formulation as a comparator in the present study.

Neuroleptics are by far the best-documented and most commonly used treatment for agitation in dementia (Devanand and Levy 1995). Currently, only the typical antipsychotics have been accessible in parenteral form until now, as no IM formulation of an atypical antipsychotic has been available in the United States. Use of the typical antipsychotics is associated with a number of drawbacks, however, including a greater incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms, endocrine disturbances (eg, prolactin elevations), and, particularly with parenteral preparations, induction of orthostatic hypotension. This is of great concern in treating elderly patients, who may be especially vulnerable to the extrapyramidal and cardiovascular effects of neuroleptics, even at low doses. The availability of an IM formulation of olanzapine may offer safety advantages in the parenteral treatment of agitation. Oral administration of olanzapine has been shown previously to control psychotic symptoms and behavioral disturbances in elderly patients with Alzheimer's disease (Clark et al. 2001; Street et al. 2000), and this drug has been especially recommended for patients with dementia who exhibit “sundowning” behavior (Expert Consensus Guideline Series 1998). Intramuscular delivery of olanzapine provides a rapidly acting treatment for agitation in aggressive or hyperactive patients or those refusing oral medication, and may confer the advantages that have been reported for other parenteral formulations over their corresponding oral preparations, such as rapid onset (Dubin et al. 1985; Schaffer et al. 1982) and higher steady-state plasma concentrations (Kahn et al. 1990; Simpson et al. 1978).

Treatment of agitation in the elderly necessitates a careful assessment of risk benefit. On the one hand, the patient's condition requires prompt and effective action to bring the agitation quickly under control. On the other hand, the fragility of the elderly patient, combined with the greater likelihood of their comorbidity and comedication, requires a cautious approach to dosing, so as to limit drug exposure and minimize risk. The minimum effective dose is best, particularly in view of evidence that higher loading doses do not necessarily bring about greater efficacy (Battaglia et al. 1997). In the present study, the dosing scheme was designed to minimize patients' drug exposure. To this end, ceilings of 12.5 mg of olanzapine, 6.25 mg of olanzapine, and 2.5 mg of lorazepam, respectively, were imposed on the three active-treatment groups. In addition, patients in the placebo group were allowed a 5.0-mg dose of olanzapine as their third injection. Levels of sedation, cognitive state, incidence of adverse events, and an objective measure of extrapyramidal symptomatology all indicated that patients in the active treatment groups did not differ significantly from patients treated with placebo in these areas.

In this study, the three active-treatment groups appeared for the most part to be comparable in efficacy. At the 2-h timepoint, all four groups had improved from baseline. Olz5.0 and Lzp were significantly superior to placebo on all three measures of efficacy, while Olz2.5 was superior on the primary measure of efficacy, the PANSS-EC. These findings are consistent with those from previous studies comparing the effects of IM administration of lorazepam and typical neuroleptics, in which lorazepam was shown to be as effective as its typical neuroleptic comparator, but with fewer associated adverse events (Foster et al. 1997; Salzman 1988; Salzman et al. 1991). Comparative studies involving a placebo comparator have been lacking, however, making interpretation of past results difficult when juxtaposed with the results of studies involving oral administration that show no difference in efficacy between the typical neuroleptic and placebo (Auchus and Bissey-Black 1997). In a metaanalysis of the use of neuroleptics to treat agitation in dementia, Schneider et al. (1990) concluded that no single typical agent was better than another, and that this class of drugs produced only modest improvement of agitated behavior, equivalent to an 18% improvement above placebo. In the present study, olanzapine brought about a 30% improvement above placebo, as measured from clinical response rates (⩾40% improvement in PANSS-EC score). The greater improvement seen here with olanzapine may therefore represent a greater efficacy of the atypical neuroleptics relative to the older typical drugs. However, this possibility remains to be substantiated in further studies of atypical versus typical neuroleptics in the treatment of agitation.

In the present study, the highest dose of olanzapine also appeared to have the fastest onset of effect. Olz5.0 showed significantly greater improvement than placebo on the PANSS-EC by the first timepoint at 30 min postinjection, and maintained this superiority at each succeeding timepoint in the 24-h study. Lorazepam required 60 min to show greater improvement than placebo, and Olz2.5, which improved significantly from baseline by the 30-min timepoint, required 2 h to separate from placebo. Both olanzapine treatments remained effective longer than lorazepam, however, as both Olz5.0 and Olz2.5 were still significantly superior to placebo on the PANSS-EC at the 24-h timepoint, whereas lorazepam no longer was. Unfortunately, little information is available on the immediate timecourse of other treatments for agitation. One study (Battaglia et al. 1997) comparing IM injection of either lorazepam or haloperidol showed the two had approximately equal timecourses in controlling agitation, but combined administration of the two was more effective than either monotherapy by the 1-h timepoint. However, this difference disappeared by the 2-h timepoint.

No significant differences were found in the improvement of levels of agitation between patients from nursing home settings versus those from hospital settings, although patients in the hospital settings showed a greater improvement in CGI-S scores of levels of dementia at 24 h. This is in spite of the fact that the nursing home patients were more severely demented, as shown by lower MMSE scores at baseline. This may indicate that the hospitalized group were temporarily underperforming on the MMSE as a result of their acute agitation. These findings are interesting, as there is little in the literature to indicate differential outcomes between patients in these two settings. On the one hand, cognitive function tends to be more impaired among hospital inpatients relative to nursing home patients (Nagatomo et al. 1997; Teitelbaum et al. 1991), and more dependent patients are more likely to be concentrated in hospital settings (Campbell et al. 1990). On the other hand, activities of daily living appear to be more impaired in nursing home patients (Nagatomo et al. 1997), and these patients show more depression and behavioral deterioration than do patients in hospital settings (Linn et al. 1985). The more severe agitation and psychopathology seen in the nursing home patients in the present study may therefore reflect the greater debilitation in behavioral state that has been seen in other analyses (Linn et al. 1985). Furthermore, the general absence of major treatment differences in the present study may represent the broad efficacy and tolerance of the pharmacological interventions, regardless of setting.

As indicated by Simpson–Angus scores, significant changes in patients' parkinsonian symptomatology were not observed in any of the three active treatment groups. This is a particular consideration in administering neuroleptics to elderly patients with dementia, who exhibit higher than normal incidences of extrapyramidal symptoms, even in the absence of previous exposure to neuroleptics (Girling and Berrios 1990). Another concern in treating the elderly is postural hypotension (Masand 2000), which can lead to dizziness and the risk of injury from falls. In the present study, no increase was observed in the incidence of hypotension or dizziness during treatment with either of the administered agents. The use of the PANSS-EC, CMAI, and ACES scales allowed a distinction to be made between the treatment-emergent sedation and improvement in levels of agitation. Mean ACES scores improved from baseline with each of the three active treatments at both the 2-h and 24-h timepoints to levels that did not exceed mild calmness, indicating that efficacy generally was achieved by both olanzapine and lorazepam without clinically significant sedation. Moreover, as indicated by the absence of any significant change in MMSE score, neither agent had any detectable effect on patients' level of cognition.

This study was not without its limitations. For example, due to the difficulty of discriminating akathisia from agitation, there were no objective measurements made of patients' levels of akathisia, nor were objective measures of dystonia used. The study relied instead on unsolicited reports of adverse extrapyramidal events to supplement the measurements made with the Simpson–Angus Scale. This was a deliberate decision based on the need to limit the number of measurements made over the brief duration of this study. On the other hand, the use of both a placebo and an active comparator is a strength of this study. Moreover, the use of not only the PANSS-EC but also the CMAI and ACES allowed discrimination between the effects of the interventions on agitation versus potential treatment-emergent sedation.

In summary, this report details the findings from the first study of the use of an IM formulation of an atypical neuroleptic in the rapid treatment of agitation in elderly patients with dementia. The results indicated that IM injection of 2.5 mg or 5.0 mg of olanzapine or 1.0 mg of lorazepam significantly improved patients' levels of agitation. The 5.0-mg dose of olanzapine had the fastest onset, and both doses of olanzapine were longer lasting than lorazepam. No significant differences among treatment groups were seen in extrapyramidal symptomatology, cognitive state, levels of sedation, or incidence of adverse events. Results from the analysis of QTc intervals did not demonstrate a significantly increased risk of QTc prolongation in patients treated with IM olanzapine or lorazepam when compared with placebo. No other clinically or statistically significant treatment differences were seen in any other vital sign, including orthostasis, or in any laboratory analyte, including nonfasting plasma glucose. These results suggest that this rapidly acting intramuscular formulation of olanzapine may contribute significantly to the treatment of patients with acute dementia-related agitation.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association

Auchus AP, Bissey-Black C . (1997): Pilot study of haloperidol, fluoxetine, and placebo in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 9: 591–593

Barclay AM . (1985): Psychotropic drugs in the elderly: selection of the appropriate agent. Postgrad Med 77: 153–157160–162

Battaglia J, Moss S, Rush J, Kang J, Mendoza R, Leedom L, Dubin W, McGlynn C, Goodman L . (1997): Haloperidol, lorazepam, or both for psychotic agitation? A multicenter, prospective, double-blind, emergency department study. Am J Emerg Med 15: 335–340

Bianchetti G, Zarifian E, Poirier-Littre MF, Morselli PL, Deniker P . (1980): Influence of route of administration on haloperidol plasma levels in psychotic patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 18: 324–327

Caligiuri MP, Lacro JP, Jeste DV . (1999): Incidence and predictors of drug-induced parkinsonism in older psychiatric patients treated with very low doses of neuroleptics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 19: 322–328

Campbell H, Crawford V, Stout RW . (1990): The impact of private residential and nursing care on statutory residential and hospital care of elderly people in south Belfast. Age Ageing 19: 318–324

Clark WS, Street JS, Feldman PD, Breier A . (2001): The effects of olanzapine in reducing the emergence of psychosis among nursing home patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry 62: 34–40

Class CA, Schneider L, Farlow MR . (1997): Optimal management of behavioural disorders associated with dementia. Drugs Aging 10: 95–106

Cohen-Mansfield J . (1986): Agitated behaviors in the elderly. II. Preliminary results in the cognitively deteriorated. J Am Geriatr Soc 34: 722–727

Cohen-Mansfield J, Billig N, Lipson S, Rosenthal AS, Pawlson LG . (1990): Medical correlates of agitation in nursing home residents. Gerontology 36: 150–158

De Deyn PP, Rabheru K, Rasmussen A, Bocksberger JP, Dautzenberg PLJ, Eriksson S, Lawlor BA . (1999): A randomized trial of risperidone, placebo, and haloperidol for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Neurology 53: 946–955

Deutsch LH, Rovner BW . (1991): Agitation and other noncognitive abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatr Clin North Am 14: 341–351

Devanand DP, Levy SR . (1995): Neuroleptic treatment of agitation and psychosis in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 8 (suppl 1):S18–S27

Dubin WR, Waxman HM, Weiss KJ, Ramchandani D, Tavani-Petrone C . (1985): Rapid tranquilization: the efficacy of oral concentrate. J Clin Psychiatry 46: 475–478

Expert Consensus Guideline Series. (1998): Treatment of agitation in older persons with dementia. In Alexopoulos GS, Silver JM, Kahn DA, Frances A, Carpenter D (eds), The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Agitation in Older Persons with Dementia. New York, McGraw-Hill Publishing, Inc., pp 1–88

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR . (1975): Mini-Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients by the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198

Foster S, Kessel J, Berman ME, Simpson GM . (1997): Efficacy of lorazepam and haloperidol for rapid tranquilization in a psychiatric emergency room setting. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 12: 175–179

Gillings D, Koch G . (1991): The application of the principle of intention-to-treat to the analysis of clinical trials. Drug Info J 25: 411–425

Girling DM, Berrios GE . (1990): Extrapyramidal signs, primitive reflexes and frontal lobe function in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Br J Psychiatry 157: 888–893

Greenblatt DJ, Divoll M . (1983): Diazepam versus lorazepam: relationship of drug distribution to duration of clinical action. Adv Neurol 34: 487–491

Gurland BJ, Cross PS . (1982): Epidemiology of psychopathology in old age: some implications for clinical services. Psychiatr Clin North Am 5: 11–26

Guy W . (1976):ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. Bethesda, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

Kahn J-P, Yisak W, Albaret C, Nilsson L, Zaar-Hedin A, Laxenaire M . (1990): Tolerability and pharmacokinetics of remoxipride after intramuscular administration. Acta Psychiat Scand 82 (suppl 358):51–53

Katz IR, Jeste DV, Mintzer JE, Clyde C, Napolitano J, Brecher M . (1999): Comparison of risperidone and placebo for psychosis and behavioral disturbances associated with dementia: a randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry 60: 107–115

Kay S, Opler L, Fiszbein A . (1986): Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Manual. North Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems

Kay SR, Sevy S . (1990): Pyramidical model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 16: 537–545

Kunik ME, Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Hales RE . (1994): Pharmacologic approach to management of agitation associated with dementia. J Clin Psychiatry 55 (suppl):13–17

Lancon C, Auquier P, Nayt G, Reine G . (2000): Stability of the five-factor structure of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Schizophr Res 42: 231–239

Lawrence KR, Nasraway SA . (1997): Conduction disturbances associated with administration of butyrophenone antipsychotics in the critically ill: a review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy 17: 531–537

Lindenmayer J-P, Grochowski S, Hyman RB . (1995): Five factor model of schizophrenia: replication across samples. Schizophr Res 14: 229–234

Linn MW, Gurel L, Williford WO, Overall J, Gurland B, Laughlin P, Barchiesi A . (1985): Nursing home care as an alternative to psychiatric hospitalization: a Veterans Administration cooperative study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42: 544–551

Marsden CD, Jenner P . (1980): The pathophysiology of extrapyramidal side-effects of neuroleptic drugs. Psychol Med 10: 55–72

Masand PS . (2000): Side effects of antipsychotics in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry 61 (suppl 8):43–49

Morganroth J, Brown AM, Critz S, Crumb WJ, Kunze DL, Lacerda AE, Lopez H . (1993): Variability of the QTc interval: impact on defining drug effect and low-frequency cardiac event. Am J Cardiol 72: 26B–31B

Nagatomo I, Iwagawa S, Takigawa M . (1997): Abnormal behavior of elderly people residing in institutions of medical and social welfare systems. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 51: 53–56

Overall JE, Gorham DR . (1962): The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 10: 799–812

Rao AV . (1996): Fluphenazine decanoate causing atrioventricular block. Indian Heart J 48: 713–714

Salzman C . (1988): Use of benzodiazepines to control disruptive behavior in inpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 49: 13–15

Salzman C, Solomon D, Miyawaki E, Glassman R, Rood L, Flowers E, Thayer S . (1991): Parenteral lorazepam versus parenteral haloperidol for the control of psychotic disruptive behavior. J Clin Psychiatry 52: 177–180

Sanger TM, Lieberman JA, Tohen M, Grundy S, Beasley C Jr, Tollefson GD . (1999): Olanzapine versus haloperidol treatment in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 156: 79–87

Schaffer CB, Shahid A, Javaid JI, Dysken MW, Davis JM . (1982): Bioavailability of intramuscular versus oral haloperidol in schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2: 274–277

Schneider LS, Pollock VE, Lyness SA . (1990): A metaanalysis of controlled trials of neuroleptic treatment in dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 38: 553–563

Schwartz JT, Brotman AW . (1992): A clinical guide to antipsychotic drugs. Drugs 44: 981–992

Simpson GM, Cooper TB, Lee JH, Young MA . (1978): Clinical and plasma level characteristics of intramuscular and oral loxapine. Psychopharmacology 56: 225–232

Small GW, Jarvik LF . (1982): The dementia syndrome. Lancet 2: 1443–1446

Street JS, Clark WS, Gannon KS, Cummings JL, Bymaster FP, Tamura RN, Mitan SJ, Kadam DL, Sanger TM, Feldman PD, Tollefson GD, Breier A . (2000): Olanzapine treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease in nursing care facilities: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 968–976

Teitelbaum L, Ginsburg ML, Hopkins RW . (1991): Cognitive and behavioural impairment among elderly people in institutions providing different levels of care. CMAJ 144: 169–173

Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson GD . (1997): Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 17: 407–418

Wolthaus JED, Dingemans PMA, Schene AH, Linszen DH, Knegtering H, Holthausen EAE, Cahn W, Hijman R . (2000): Component structure of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in patients with recent onset schizophrenia and spectrum disorders. Psychopharmacology 150: 399–403.

Wood S, Cummings JL, Hsu MA, Barclay T, Wheatley MV, Yarema KT, Schnelle JF . (2000): The use of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in nursing home residents. Characterization and measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 8: 75–83

Wright P, Birkett M, Meehan K, Ferchland I, David S, Alaka K, Pullen P, Brook S, Reinstein M, Breier A . (2000): A double-blind study of intramuscular olanzapine, haloperidol and placebo in acutely agitated schizophrenic patients [abstract]. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 3 (suppl 3):S139

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meehan, K., Wang, H., David, S. et al. Comparison of Rapidly Acting Intramuscular Olanzapine, Lorazepam, and Placebo: A Double-blind, Randomized Study in Acutely Agitated Patients with Dementia. Neuropsychopharmacol 26, 494–504 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00365-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00365-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sublingual Dexmedetomidine for Agitation Associated with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder: A Post Hoc Analysis of Number Needed to Treat, Number Needed to Harm, and Likelihood to be Helped or Harmed

Advances in Therapy (2022)

-

Pharmacological Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia

Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry (2020)

-

Subjective Versus Objective Outcomes of Antipsychotics for the Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Associated with Dementia

CNS Drugs (2019)

-

QTc Interval Prolongation and Torsade de Pointes Associated with Second-Generation Antipsychotics and Antidepressants: A Comprehensive Review

CNS Drugs (2014)

-

A prospective study of high dose sedation for rapid tranquilisation of acute behavioural disturbance in an acute mental health unit

BMC Psychiatry (2013)