Abstract

The frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia is a significant neurological condition worldwide. There exist few treatments available for the cognitive and behavioural sequelae of fvFTD. Previous research has shown that these patients display risky decision-making, and numerous studies have now demonstrated pathology affecting the orbitofrontal cortex. The present study uses a within-subjects, double-blind, placebo-controlled procedure to investigate the effects of a single dose of methylphenidate (40 mg) upon a range of different cognitive processes including those assessing prefrontal cortex integrity. Methylphenidate was effective in ‘normalizing’ the decision-making behavior of patients, such that they became less risk taking on medication, although there were no significant effects on other aspects of cognitive function, including working memory, attentional set shifting, and reversal learning. Moreover, there was an absence of the normal subjective and autonomic responses to methylphenidate seen in elderly subjects. The results are discussed in terms of the ‘somatic marker’ hypothesis of impaired decision-making following orbitofrontal dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

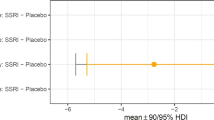

The frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia (fvFTD) is a clinically significant neurological problem that constitutes one of the most prevalent forms of early-onset dementia (Ratnavalli et al, 2002). There currently exist few treatments available for the amelioration of the cognitive and behavioral deficits in fvFTD, in stark contrast to the management options for dementia of the Alzheimer type (Rahman et al, 2000). An initial study by Coull et al (1996) showed that the α2 noradrenergic antagonist idazoxan produced cognitive improvements in patients with fvFTD on tests of planning, sustained attention, verbal fluency, and episodic memory. Idazoxan was thought to increase coerulo-cortical noradrenaline (NA) activity via presynaptic effects. There has also been some interest in using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of frontotemporal dementia, but we have previously found little objective benefit of a chronic dosage regimen of paroxetine (Deakin et al, 2004a).

Previous work has demonstrated that the psychostimulant methylphenidate (Ritalin) improves higher level cognitive function in healthy volunteers, on tests of working memory and planning (Elliott et al, 1997; Mehta et al, 2000). Methylphenidate increases synaptic and extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) and NA (Scheel-Krüger, 1971) via blockade of the reuptake transporters in the striatum (Volkow et al, 1998). There has been historical interest in methylphenidate, as it has been used for many years in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disorders of sleep and arousal such as narcolepsy (Aron et al, 2003; Conners and Eisenberg, 1963). The cognition-enhancing effects of methylphenidate have been investigated in patients with brain injury, with some studies demonstrating improvements (Gualtieri and Evans, 1998; Plenger et al, 1996; Whyte et al, 1997), but others failing to find beneficial effects (Speech et al, 1993; Williams et al, 1998). Methylphenidate has been studied as an adjuvant medication for the treatment of depression and apathy in various disorders (Marin et al, 1995; Chatterjee and Fahn, 2002). Analyses of the neurochemical correlates of FTD based on autopsy tissue have generally implicated deficits in DA and NA neurotransmission (Bettendorff et al, 1997; Francis et al, 1993; Gilbert et al, 1988; Nagaoka et al, 1995; Sjogren et al, 1998; Sparks and Markesbery, 1991). For example, Sjogren et al (1998) reported a significant reduction in the CSF concentration of homovanillic acid, a major metabolite of DA, in a large sample of frontotemporal dementia cases. This indication of DA pathology in fvFTD highlights the therapeutic potential of methylphenidate in this condition.

We originally proposed that the orbitofrontal cortex was a major locus of aberrant function in fvFTD (Rahman et al, 1999; Mendez and Cummings, 2003). Neurocognitive assessment indicated risk-taking behavior in the domain of decision-making and deficits in reversal learning, which resemble the cognitive sequelae of orbitofrontal cortex lesions (Damasio, 1996; Rolls et al, 1994). These reward-based deficits are considered to be one of the main problems that fvFTD patients face (La Coco and Nacci, 2004), in contrast to the episodic memory dysfunction found in the dementia of Alzheimer type (eg Lee et al, 2003). Neuroanatomical evidence for orbitofrontal dysfunction has been borne out in subsequent post mortem and in vivo neuroimaging studies (Ibach et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004; Diehl et al, 2004; Kobayashi et al, 1999). For example, a European multicentre PET study showed that the ventromedial frontopolar cortex was critically affected in every one of 29 fvFTD cases (Salmon et al, 2003).

The ascending mesocorticolimbic DA projection into the prefrontal cortex has a critical role in signaling reward-related information (Hollerman and Schultz, 1998), and a fronto-striatal circuit comprising the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex has been implicated in a range of emotional processes and affective disorders (Alexander et al, 1986; Mega and Cummings, 1994). We hypothesized that methylphenidate would ameliorate reward-based deficits in fvFTD by stimulating dopaminergic transmission in orbitofrontal fronto-striatal circuitry. We have previously reported no significant effects on decision-making cognition in healthy elderly volunteers receiving a single 40 mg dose of methylphenidate (Turner et al, 2003). However, healthy elderly volunteers tend to be more conservative and show reduced risk-taking behavior compared to young adults (Deakin et al, 2004b), whereas fvFTD patients show increased risk-taking behavior compared to age-matched controls (Rahman et al, 1999). The present study sought to explore the cognition-enhancing properties of methylphenidate in fvFTD on a neuropsychological assessment focusing on measures of prefrontal cortical function, including reward-based learning and working memory, and temporal lobe memory function (visual recognition memory).

METHODS

Participants

Eight patients were recruited with a clinical diagnosis of fvFTD according to the Lund and Manchester Groups (1994) criteria. The eight patients are labelled A-H in Figure 1. A full medical history was taken prior to testing by specialist registrar in neurology (PJN). Patient B was female; the rest were male. Patients were all Caucasian, with a mean age of 62.0 years (SD 10.1). Four patients were current smokers (A, B, F, H). The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al, 1975) was administered with an exclusion threshold of 20, which would preclude computerized assessment (mean score 27.0, SD 1.7). Premorbid verbal intelligence was assessed with the National Adult Reading Test (mean 110.7, SD 6.2). Subjects were asked to abstain from alcohol intake on the evenings before test sessions or excessive caffeine intake on the mornings of test sessions. Possible risks and benefits were explained to all patients and caregivers before seeking informed consent for the study. The study was approved by the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee and the Department of Health Medicines Controls Agency. Patients were excluded if the severity of dementia precluded computerized neuropsychological assessment (MMSE <20), or if they suffered from concomitant illness likely to confound the interpretation of findings. Five patients were currently receiving medication: atenolol 25 mg/day (patient H), vitamin E tablets (patient F), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (patient A), chlorpromazine 150 mg/day, fluoxetine 20 mg/day and diazepam 15 mg/day (patient B), and hormone replacement therapy and diclofenac (patient C). A total of 11people were originally screened for the study, of which three were excluded from participating in the study, due to concomitant illnesses, which contraindicated the use of methylphenidate (glaucoma, unstable hypertension, and stable/unstable angina).

(a) Methylphenidate significantly reduced betting behavior on the Cambridge Gamble Task. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean. (b) The reduction in betting behavior in fvFTD patients on methylphenidate normalizes task performance, that is, performance approaches of healthy older adults. *Healthy data from the placebo condition of Turner et al (2003), in 20 male volunteers aged 55–69 years (mean age 61 years). (c) Individual data in the fvFTD group show that the reduction in betting is apparent in every subject.

Procedure

This study followed a double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design. In this design, the performance of each subject is measured twice, once following administration of an active drug and once following administration of a placebo. The two test sessions for each subject were separated by 1–2 weeks and treatment order was fully counter-balanced across subjects. The groups that had taken drug first (A, D, F, H) or placebo first (B, C, E, G) were matched for age, MMSE, and NART IQ estimate (age: F(1,6)=0.215, P=0.659; MMSE: F(1,6)=0.667, P=0.445; NART: F(1,6)=2.48, P=0.166). All test sessions were in the afternoon, with ingestion of the drug or placebo at approximately 1430 hours. A 40 mg dose of methylphenidate was used, with cognitive testing commencing at 90 min after administration (for about 2 h). Peak plasma concentrations of methylphenidate are reached approximately 2 h after ingestion (half-life in plasma 1–2 h, mean systemic clearance is 10 l/h/kg) (Gilman et al, 1980; see also Turner et al (2003) and Muller et al (2005) for older healthy adults). Adverse effects during the session were monitored and recorded, with particular care to identify any nervousness, headache, and gastrointestinal disturbances. Blood pressure was measured using a traditional sphygmomanometer immediately prior to ingestion of the tablet, and just prior to cognitive testing (at +90 min). Visual analog scales (Bond and Lader, 1974) were administered prior to tablet ingestion and just prior to cognitive testing, for the scales alert–drowsy, calm–excited, strong–feeble, muzzy–clear headed, well coordinated–clumsy, lethargic–energetic, contented–discontented, troubled–tranquil, mentally slow–quick witted, tense–relaxed, attentive–dreamy, incompetent–proficient, happy–sad, antagonistic–amicable, interested–bored and withdrawn-gregarious. A restricted threshold of P=0.01 was set to represent a significant difference between scores in order to reduce the chance of a type I error.

Cognitive Assessment

In both test sessions, the patients were given the same assessment in a fixed order, consisting of a computerized assessment including established tasks from the CANTAB battery (www.camcog.com): pattern recognition memory, spatial recognition memory, spatial span, spatial working memory, and ID/ED attentional set-shifting (see Rahman et al, 1999 for descriptions). The one-touch version of the CANTAB Tower of London test of spatial planning was also administered (Owen et al, 1995). Finally, the Cambridge Gamble Task (Rogers et al, 1999) was used to assess decision-making cognition. In this task, subjects are presented with an array of 10 red or blue boxes on each trial. The ratio of red : blue boxes varies across trials in a pseudo-random sequence (6 : 4, 7 : 3, 8 : 2, 9 : 1). The subject is informed that the computer has hidden a token, at random, under one of the boxes, and they must decide whether the token is hidden under a red or a blue box. After making this probabilistic judgment (they should always select the color in the majority), subjects must place a bet on their confidence in the decision. Bets are generated by the computer in either an ascending or descending sequence, with the available bets in percentages of the current points total (5, 25, 50, 75, and 95%). After the bet is placed, the location of the token is revealed and the points bet are either added or deducted from the running total. Subjects perform four blocks of 10 trials in each condition (ascending or descending bets), where at the start of each block the subject returns to 100 points.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were run in SPSS version 9.0 with two-tailed statistics thresholded at P<0.05. In the crossover design, it is the difference between the two test sessions that denotes the effect of the treatment. Given the small group sizes, data were analyzed using nonparametric statistics. Drug effects were tested by comparing the methylphenidate and placebo scores within-subjects using a Wilcoxon signed-ranks test (as described in Howell, 1997). This test is a distribution-free analog for related samples.

RESULTS

Cognitive Assessment

Neuropsychological performance is shown in Table 1. There were no effects of methylphenidate on pattern recognition memory, spatial recognition memory, spatial working memory, ID/ED attentional set-shifting, and one-touch Tower of London tasks. A marginally significant (detrimental) effect on spatial span on the span score (P=0.096) was not apparent on usage errors on this task (P=0.612).

Data for the Cambridge Gamble Task are shown in Figures 1 and 2. There were no effects of methylphenidate on the average deliberation time (Z=−0.280, P=0.779) or choice of the likely outcome (Z=−0.170, P=0.865) (see Figure 2). The difference in betting behavior (Figure 1) in the drug and placebo conditions was statistically significant (Z=−2.38, P=0.017), with patients demonstrating reduced betting on methylphenidate. This was a consistent effect across all eight patients. To further evaluate the changes in betting behavior on methylphenidate, a two (drug: methylphenidate, placebo) × 2 (condition: ascend, descend) × 4 (ratio: 9 : 1, 8 : 2, 7 : 3, 6 : 4) × 2 (order of drug administration) mixed-model ANOVA was performed. There was a significant main effect of drug (F1,6=7.73, P=0.032), supporting the effect in the nonparametric test. The main effects of order (F1,6=0.570, P=0.479) and drug × order interaction term (F1,6=1.37, P=0.287) were both nonsignificant. The main effect of condition (F1,6=1.60, P=0.253) was not significant, although, on average, subjects did place higher bets in the descend condition than in the ascend condition (methylphenidate: ascend mean=58.8 (SD 22.0), descend mean=65.5 (SD 19.8); placebo: ascend mean=66.5 (SD 22.8), descend mean=75.9 (SD 13.0)), consistent with previous studies using the Cambridge Gamble Task (eg Clark et al, 2003; Mavaddat et al, 2000). Similarly, the main effect of ratio was not significant (Greenhouse–Geisser correction F1.42,8.52=2.17, P=0.177), although, on average, subjects placed higher bets at the 9 : 1 ratio compared to the 6 : 4 ratio (see Figure 1). All interaction terms in the ANOVA model were nonsignificant (P>0.10).

Cardiovascular and Subjective Measures

Cardiovascular measures at baseline and prior to cognitive testing are shown in Table 2. Baseline measurements of pulse (Z=−0.632, P=0.528) and systolic blood pressure (Z=−1.20, P=0.231) did not differ significantly between drug and placebo sessions, although the baseline measurements of diastolic blood pressure approached significance (Z=−1.87, P=0.061). There was no overall difference in pulse (ie change from baseline) for the drug condition compared to the placebo condition (Z=−0.943, P=0.345). While there was a general increase in blood pressure after methylphenidate, the differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure for the drug condition compared to the placebo condition approached significance (systolic blood pressure: Z=−1.78, P=0.075; diastolic blood pressure: Z=−1.78, P=0.075). However, these comparisons were nonsignificant when the subject receiving atenolol was excluded from the analysis (systolic blood pressure Z=−1.48, P=0.138; diastolic blood pressure Z=−1.58, P=0.115). For the visual analog scales, the change from baseline score was calculated for each drug session. There was no effect of drug on any of these changes compared to placebo.

DISCUSSION

This study reported the effects of methylphenidate upon subjective mood, cardiovascular activity, and a range of cognitive functions in patients with fvFTD. The key finding was an attenuation of risk-taking following methylphenidate, on a laboratory measure of decision-making (the Cambridge Gamble Task). This was a relatively selective effect: there were no significant effects of drug treatment on tasks of memory function associated with temporal lobe integrity (recognition memory) or executive tasks associated with dorsolateral prefrontal function (planning, extra-dimensional shifting and working memory). In a previous study of methylphenidate effects in healthy older adults (aged 55–69 years, mean age=61 years), we did not detect any significant effects of this medication on risk-taking on the Cambridge Gamble Task (Turner et al, 2003). We infer that the significant effect of methylphenidate on risk-taking in patients with fvFTD is associated with the behavioral disturbance induced by the dementia. This effect also shows some neurochemical specificity: we have shown previously that chronic treatment with the selective SSRI paroxetine did not affect performance on the Cambridge Gamble Task in an independent group of fvFTD patients (Deakin et al, 2004a). The amelioration of risk-taking behavior in fvFTD by methylphenidate carries important implications for rehabilitative approaches, given that neurobehavioral deficits including risky behavior and disinhibition represent a significant barrier for social interaction and everyday functioning within society.

Under baseline conditions, we have shown previously that patients with fvFTD displayed increased betting behavior on the Cambridge Gamble Task compared to matched healthy controls (Rahman et al, 1999). This increased betting was apparent across all ratios of boxes, in both the ascending and descending conditions of the task (Rahman et al, 1999). The action of methylphenidate in the present study was to normalize risk-taking behavior, bringing the fvFTD patients toward the typical performance of healthy older adults (see Figure 1b, with healthy performance taken from Turner et al (2003)). The order of drug administration was fully counter balanced and order did not have a significant effect in the analysis of betting performance. The discrepancy between the ascending and descending conditions on the Cambridge Gamble Task can provide an index of impulsivity or delay aversion. Impulsive or impatient subjects are expected to place high bets in the descend condition but low bets in the ascend condition, whereas a genuine risk-preferent subject would wait in order to place high bets in the ascend condition (see Cools et al, 2003). In the present study, the effect of methylphenidate to reduce betting did not interact with the ratio of boxes, and did not interact with the ascend vs descend betting condition. As such, it seems unlikely that the normalizing effect of methylphenidate results from an ‘antiimpulsive’ action similar to that seen in ADHD (Aron et al, 2003; Tannock et al, 1989).

The beneficial effects of methylphenidate on decision-making in fvFTD may be mediated at the level of the orbitofrontal cortex, the striatum, or the connectivity between these two regions. Neuropathology in the orbitofrontal cortex is a consistent feature of fvFTD (eg Salmon et al, 2003) and is thought to underlie the risk-taking behavior seen under baseline conditions (Rahman et al, 1999). However, the DA transporters that are targeted by methylphenidate are located predominantly within the striatum. The DA projection from the midbrain to the ventral striatum is known to signal reward-related information (Schultz, 2002): specifically, the temporal discrepancy between the occurrence and the prediction of reward (the reward prediction error) (Hollerman and Schultz, 1998). It is possible that neuropathology affecting the DA system in fvFTD (eg Sjogren et al, 1998) may increase reward-driven behavior under baseline conditions. Stimulation of DA neurotransmission by methylphenidate may conceivably normalize these changes. In addition, DA stimulation by methylphenidate appears to modulate orbitofrontal cortex activity: methylphenidate administration significantly increased glucose metabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex of cocaine addicts (Volkow et al, 2005), who also display increased risk taking (Bartzokis et al, 2000). These increases in orbitofrontal metabolism were correlated with methylphenidate-induced changes in thalamic DA binding, suggesting a modulatory role of the mesothalamic DA projection (Volkow et al, 2005).

An alternative explanation is that the effect on decision-making cognition may reflect the action of methylphenidate to produce or modulate central ‘somatic markers’ (Damasio, 1996) via stimulation of the ascending catecholamine systems. Through connectivity with the amygdala and somatosensory cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex may contribute to decision-making by retrieving somatic information associated with the outcomes of similar decisions in the past (Bechara, 2003; Bechara et al, 2003; Damasio, 1996). These somatic states facilitate an exhaustive cost–benefit analysis of decision-making. The amygdala may predominantly mediate the elicitation of emotional responses by conditioned or unconditioned stimuli (‘primary inducers’), whereas the orbitofrontal cortex elicits emotional arousal by thoughts, memories, and hypothetical decisions (‘secondary inducers’) (Bechara et al, 2003). Via dopaminergic innervation of the orbitofrontal cortex (Oades and Halliday, 1987) and amygdala (Fallon et al, 1978), methylphenidate may modulate or mimic these somatic representations in a decision-making context.

Dysfunction in somatic- and emotion-related circuitry may also impair the monitoring of internal state. In the present study, we were unable to demonstrate any significant effects of methylphenidate on subjective mood. This is perhaps remarkable in itself: in previous research, methylphenidate robustly increased subjective ratings of alertness and energy in healthy volunteers (Elliott et al, 1997; Heishman and Henningfield, 1991), including elderly volunteers (Turner et al, 2003). The lack of subjective effects in fvFTD implies that these patients are unable to sense differences in their internal state following drug administration. The cardiovascular effects of methylphenidate were unclear in the present study. There was a subtle effect of methylphenidate to increase systolic and diastolic blood pressure. However, this effect only reached trend levels of significance. In addition, baseline diastolic blood pressure was somewhat lower on the methylphenidate session, and therefore, we cannot rule out a regression to the mean effect. Future research is needed in a larger group of patients to confirm whether there is a genuine dissociation between the subjective and cardiovascular effects of methylphenidate in fvFTD patients.

Economic models distinguish decision-making under risk (when outcome probabilities are explicit) from decision-making under ambiguity (when outcome probabilities are undefined) (Ellsberg, 1961; Smith et al, 2002). Bechara et al, (2001) and Bechara (2003) have recently investigated the effects of a DA manipulation on the Iowa Gambling Task. On this task, subjects make a series of choices from four decks of cards that vary in the magnitude and frequency of winning and losing. Subjects are provided with no information about the differing contingencies of the four decks; consequently, the early stages of the task emphasize decision-making under ambiguity. Bechara et al (2001, 2003) reported bidirectional modulation of choice behavior by the dopaminergic agents dextroamphetamine and haloperidol, but these effects were restricted to the early part of the task when outcome probabilities were not well defined. In contrast, the modulatory effects of methylphenidate on the Cambridge Gamble Task suggest that DA predominantly manipulates decision-making under risk, as this task explicitly presents trial-by-trial probabilities. However, it is possible that the cognitive impairment present in these fvFTD patients may have affected their explicit knowledge of risk on the Cambridge Gamble Task, and as such, these decisions may have also been made under ambiguity.

In the present study, there was no effect of methylphenidate on reversal learning on the ID/ED task. Reversal learning is also robustly linked to orbitofrontal integrity (Clark et al, 2004) and was impaired in fvFTD patients in our previous investigation (Rahman et al, 1999). This suggests some parcellation at a neurochemical level within the orbitofrontal cortex. These data are consistent with accumulating evidence using a marmoset analog of the ID/ED task, showing that reversal learning is sensitive to prefrontal 5-HT depletion but not prefrontal DA depletion (Clarke et al, 2004; Crofts et al, 2001). The lack of effect of methylphenidate on traditional measures of executive function, including working memory and planning, suggests a practical limitation on the use of this agent to treat cognitive dysfunction in fvFTD. It is notable that the level of performance of the patients in the present study was somewhat more impaired than that of the mild patients reported previously (Rahman et al, 1999). Mild cases may stand to benefit more from cognition-enhancing medication. A previous study by Coull et al (1996) showed that idazoxan, an α2 NA antagonist that acts presynaptically to elevate NA activity, produced several instances of cognitive improvement in fvFTD, but impaired spatial working memory. Recent neuropathological findings support the notion that NA neurotransmission is abnormal in fvFTD, with levels reduced by at least 30% in the nucleus basalis, thalamus, locus coeruleus, and amygdala (Nagaoka et al, 1995). It is possible that some cognitive effects associated with DA or NA challenges may be cancelled out by the combined actions of methylphenidate on catecholamine neurotransmission. Future research may utilize more selective DA agents such as the D2 agonist bromocriptine. Some further limitations of the present study are the small number of participants, the use of an acute (ie single dose) study design, and the presence of additional medications in five of the eight patients, which may interact with the effects of methylphenidate. These encouraging findings must be treated as preliminary and require extension and replication in a larger sample size with a chronic treatment design.

References

Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL (1986). Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Ann Rev Neurosci 9: 357–381.

Aron AR, Dowson JH, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2003). Methylphenidate improves response inhibition in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 54: 1465–1468.

Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Beckson M, Rapoport R, Grant S, Wiseman EJ et al (2000). Abstinence from cocaine reduces high-risk responses on a gambling task. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 102–103.

Bechara A (2003). Emotion, decision-making and addiction. J Gamb Stud 19: 23–51.

Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio A (2001). Manipulation of dopamine and serotonin causes different effects on covert and overt decision-making. Soc Neurosci Abstracts 27: 456.5.

Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR (2003). Role of the amygdala in decision-making. Ann NY Acad Sci 985: 356–369.

Bettendorff L, Mastrogiacomo F, Wins P, Kish SJ, Grisar T, Ball MJ (1997). Low thiamine phosphate levels in brains of patients with frontal lobe degeneration of the non-Alzheimer's type. J Neurochem 69: 2005–2010.

Bond A, Lader M (1974). The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. Br J Med Psychol 47: 211–218.

Chatterjee A, Fahn S (2002). Methylphenidate treats apathy in Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 14: 461–462.

Clark L, Cools R, Robbins TW (2004). The neuropsychology of ventral prefrontal cortex: decision-making and reversal learning. Brain Cogn 55: 41–53.

Clark L, Manes F, Antoun N, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2003). The contributions of lesion laterality and lesion volume to decision-making deficits following frontal lobe damage. Neuropsychologia 41: 1474–1483.

Clarke HF, Dalley JW, Crofts HS, Robbins TW, Roberts AC (2004). Cognitive inflexibility after prefrontal serotonin depletion. Science 304: 878–880.

Conners C, Eisenberg L (1963). The effects of methylphenidate on symptomatology and learning in disturbed children. Am J Psychiatry 120: 458–464.

Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2003). L-Dopa medication remediates cognitive inflexibility, but increases impulsivity in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia 41: 1431–1441.

Coull JT, Sahakian BJ, Hodges JR (1996). The alpha(2) antagonist idazoxan remediates certain attentional and executive dysfunction in patients with dementia of frontal type. Psychopharmacology 123: 239–249.

Crofts HS, Dalley JW, Collins P, Van Denderen JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW et al (2001). Differential effects of 6-OHDA lesions of the frontal cortex and the caudate nucleus on the ability to acquire an attentional set. Cereb Cortex 11: 1015–1026.

Damasio AR (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philos Trans R Soc London B 351: 1413–1420.

Deakin JB, Aitken MRF, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2004b). Risk-taking during decision-making in normal volunteers changes with age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 10: 590–598.

Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, Hodges JR, Sahakian BJ (2004a). Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology 172: 400–408.

Diehl J, Grimmer T, Drzezga A, Riemenschneider M, Forstl H, Kurz A (2004). Cerebral metabolic patterns at early stages of frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. A PET study. Neurobiol Aging 25: 1051–1056.

Elliott R, Sahakian BJ, Matthews K, Bannerjea A, Rimmer J, Robbins TW (1997). Effects of methylphenidate on spatial working memory and planning in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 131: 196–206.

Ellsberg D (1961). Risk, ambiguity and the savage axioms. Q J Econ 75: 643–669.

Fallon JH, Koziell DA, Moore RY (1978). Catecholamine innervation of the basal forebrain II. Amygdala, suprarhinal cortex and entorhinal cortex. J Comp Neurol 180: 501–532.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975). Mini mental state: a practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198.

Francis PT, Holmes C, Webster MT, Stratmann GC, Procter AW, Bowen DM (1993). Preliminary neurochemical findings in non-Alzheimer dementia due to lobar atrophy. Dementia 4: 172–177.

Gilbert JJ, Kish SJ, Chang LJ, Morito C, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O (1988). Dementia, Parkinsonism, and motor neurone disease: neurochemical and neuropathological correlates. Ann Neurol 24: 688–691.

Gilman AG, Goodman LS, Gilman A (eds) (1980). Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. MacMillan: New York.

Gualtieri CT, Evans RW (1998). Stimulant treatment for the neurobehavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2: 273–290.

Heishman SJ, Henningfield JE (1991). Discriminative stimulus effects of d-amphetamine, methylphenidate and diazepam. Psychopharmacology 103: 436–442.

Hollerman JR, Schultz W (1998). Dopamine neurons report an error in the temporal prediction of reward during learning. Nat Neurosci 1: 304–309.

Howell DC (1997). Statistical Methods for Psychology, 4th edn. Duxbury Press: Boston.

Ibach B, Poljansky S, Marienhagen J, Sommer M, Manner P, Hajak G (2004). Contrasting metabolic impairment in frontotemporal degeneration and early onset Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage 23: 739–743.

Kobayashi K, Hayashi M, Fukutani Y, Miyazu K, Shiozawa M, Aoki T . et al (1999). KP1 expression in ghost Pick bodies, amyloid P-positive astrocytes and selective nigral degeneration in early Pick's disease. Clin Neuropathol 18: 240–249.

La Coco D, Nacci P (2004). Frontotemporal dementia presenting with pathological gambling. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 16: 117–118.

Lee AC, Rahman S, Hodges JR, Sahakian BJ, Graham KS (2003). Associative and recognition memory for novel objects in dementia: implications for diagnosis. Eur J Neurosci 18: 1660–1670.

Liu W, Miller BL, Kramer JH, Rankin K, Wyss-Coray S, Gearhart P et al (2004). Behavioural disorders in the frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 62: 742–748.

Lund and Manchester Groups (1994). Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57: 416–418.

Marin RS, Fogel BS, Hawkins J, Duffy J, Krupp B (1995). Apathy: a treatable syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 7: 23–30.

Mavaddat N, Kirkpatrick PJ, Rogers RD, Sahakian BJ (2000). Deficits in decision-making in patients with aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery. Brain 123: 2109–2117.

Mega MS, Cummings JL (1994). Frontal–subcortical circuits and neuropsychiatric disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 6: 358–370.

Mehta MA, Calloway P, Sahakian BJ (2000). Amelioration of specific working memory deficits by methylphenidate in a case of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Psychopharmacol 14: 299–302.

Mendez MF, Cummings JL (2003). Frontotemporal dementia and the asymmetric cortical atrophies. In: Dementia: A Clinical Approach. Butterworth-Heinemann: Philadelphia, PA. pp 179–234

Muller U, Suckling J, Zelaya F, Honey G, Faessel H, Williams SCR et al (2005). Plasma level-dependent effects of methylphenidate on task-related functional magnetic resonance imaging signal changes. Psychopharmacology, April 14 [Epub ahead of print].

Nagaoka S, Arai H, Iwamoto N, Ohwada J, Ichimiya Y, Nakamura M et al (1995). A juvenile case of frontotemporal dementia: neurochemical and neuropathological investigation. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 19: 1251–1261.

Oades RD, Halliday GM (1987). Ventral tegmental (A10) system: neurobiology. 1. Anatomy and connectivity. Brain Res 434: 117–165.

Owen AM, Sahakian BJ, Hodges JR, Summers BA, Polkey CE, Robbins TW (1995). Dopamine-dependent frontostriatal planning deficits in early Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychology 9: 126–140.

Plenger PM, Dixon CE, Castillo RM, Frankowski RF, Yablon SA, Levin HS (1996). Subacute methylphenidate treatment for moderate to moderately-severe traumatic brain injury: a preliminary double-blind placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 77: 536–540.

Rahman S, Sahakian BJ, Hodges JR, Rogers RD, Robbins TW (1999). Specific cognitive deficits in early frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 122: 1469–1493.

Rahman S, Sahakian BJ, Gregory CA (2000). Therapeutic strategies in early onset dementia. In: Hodges JR (ed). Early Onset Dementia—A Multidisciplinary Approach. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR (2002). Prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 58: 1615–1621.

Rogers RD, Everitt BJ, Baldacchino A, Blackshaw AJ, Swainson R, Wynne K et al. (1999). Dissociable deficits in the decision-making cognition of chronic amphetamine abusers, opiate abusers, patients with focal damage to prefrontal cortex, and tryptophan-depleted normal volunteers: evidence for monoaminergic mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 20: 322–339.

Rolls ET, Hornak J, Wade D, McGrath J (1994). Emotion-related learning in patients with social and emotional changes associated with frontal lobe damage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57: 1518–1524.

Salmon E, Garraux G, Delbeuck X, Collette F, Kalbe E, Zuendorf G et al (2003). Predominant ventromedial frontotemporal metabolic impairment in frontotemporal dementia. Neuroimage 20: 435–440.

Scheel-Krüger J (1971). Comparative studies of various amphetamine analogues demonstrating different interactions with the metabolism of the catecholamines in the brain. Eur J Psychopharmacology 14: 47–59.

Schultz W (2002). Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron 36: 241–263.

Sjogren M, Minthon L, Passant K, Wallin A (1998). Decreased monoamine metabolites in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 19: 379–384.

Smith K, Dickhaut J, McCabe K, Pardo JV (2002). Neuronal substrates for choice under ambiguity, risk, gains and losses. Management Sci 48: 711–718.

Sparks DL, Markesbery WR (1991). Altered serotonergic and cholinergic synaptic markers in Pick's disease. Arch Neurol 48: 796–799.

Speech TJ, Rao SM, Osmon DC, Sperry DT (1993). A double-blind controlled study of methylphenidate treatment in closed head injury. Brain Injury 7: 333–338.

Tannock R, Schachar R, Carr RP, Chajczyk D, Logan GD (1989). Effects of methylphenidate on inhibitory control in hyperactive children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 17: 473–491.

Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ (2003). Relative lack of cognitive effects of methylphenidate in elderly volunteers. Psychopharmacology 168: 455–464.

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Gatley SJ, Logan J, Ding YS et al (1998). Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry 155: 1325–1331.

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ma Y, Fowler JS, Wong C, Ding YS et al (2005). Activation of orbital and medial prefrontal cortex by methylphenidate in cocaine-addicted subjects but not in controls: relevance to addiction. J Neurosci 25: 3932–3939.

Whyte J, Hart T, Schuster K, Fleming M, Polansky M, Corlett HB (1997). Effects of methylphenidate on attentional function after traumatic brain injury: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 76: 440–450.

Williams SE, Ris MD, Ayyanger R, Schefft BK, Berch D (1998). Recovery in pediatric brain injury: is psychostimulant medication beneficial? J Head Trauma Rehabil 13: 73–81.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and carers for participating in this study, which was funded by a Wellcome Trust Programme grant awarded to TWR, BJS, BJ Everitt, and AC Roberts, and completed within the MRC Centre for Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience in Cambridge. BJS and TWR are consultants for Cambridge Cognition Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, S., Robbins, T., Hodges, J. et al. Methylphenidate (‘Ritalin’) can Ameliorate Abnormal Risk-Taking Behavior in the Frontal Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 651–658 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300886

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300886

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

Nature Reviews Disease Primers (2023)

-

Late-manifestation of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in older adults: an observational study

BMC Psychiatry (2022)

-

Deficient neurotransmitter systems and synaptic function in frontotemporal lobar degeneration—Insights into disease mechanisms and current therapeutic approaches

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Managing the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

Current Treatment Options in Neurology (2022)

-

Pharmacotherapy for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Frontotemporal Dementia

CNS Drugs (2021)