Abstract

The participation rate in a maternal serum screening for trisomy 21 was 84% in the Helsinki trial. Six hundred and twenty-five mothers who had a positive result and a random sample of 245 mothers who had a negative result took part in the opinion survey. Ninety-five percent of the first and 97% of the second group considered the screening tests as very or quite useful. However, 12% of those with a positive result would decide against taking the test if they could reconsider, whereas 100% of those with a negative result would take it again. Too little information about the test, worries and stress, unnecessary in cases of false timing, difficult decision-making, and anxiety while awaiting the results of the chromosome study were the main complaints. More information at all stages, earlier testing, ultrasound timing before the serum test, and fast results were considered essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Screening for fetal chromosome anomalies at advanced maternal age has been offered in all parts of Finland since 1977. During 1984–1988, the participation rate was 65–75% in the southern parts of the country and 45–55% in the northern, more sparsely inhabited parts [1]. An age limit of 37 or 38 years was used in most areas at the time.

Maternal serum screening for Down’s syndrome (DS) [2] has enabled young women to take advantage of prenatal chromosome studies. It is a major challenge to inform all pregnant women about the test and the possible consequences of taking the test, especially if they are not yet familiar with screening by alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). Older mothers are usually aware of their elevated risk for chromosome anomalies before pregnancy. They often have decided in advance to have fetal chromosome studies, whereas a screening result indicating an elevated risk for DS is always alarming in the middle of pregnancy, and further studies cause more anxiety [3, 4].

When a trial of maternal serum screening for DS was begun in May 1990 on a population basis, we decided to additionally evaluate the experiences of the participating mothers. Studies on the opinions of mothers with regard to serum screening for DS has been reported from the Netherlands [5, 6]; attitudes towards prenatal testing [7], knowledge of the serum test [8], and the experiences of 20 women with positive results [9] have been reported from the United Kingdom. Experiences of the medical personnel, midwives [10] and obstetricians [11] have also been studied in the United Kingdom. The main problems that remain are how to inform the mothers adequately about the test and the meaning of the results, and how to minimize anxiety caused by positive screening results.

Materials and Methods

Screening for DS by maternal serum AFP, unconjugated oestriol during the first year, and hCG was started as a trial over a period of 2.5 years in the city of Helsinki. Finns are bilingual in some coastal areas like Helsinki (Finnish or Swedish as their native language), 87% are protestants (evangelic Lutheran), 10% are not members of any religious association. Other nationalities make up less than 1% of the population. Maternal serum screening was offered to all, but those who were 37 years or more could choose amniocentesis (AC) or chorionic villus sampling (CVS) directly as previously. Ninety-nine percent of the participants were under 37 years of age and 92% were under 35. The mean maternal age was 29 years.

The risk calculations were computed using the Alpha program developed by Logical Medical Systems Ltd., London, UK. A risk for DS of equal to or greater than 1/350 at birth was used as the cut-off value. The false-positive rate, including false high AFP results, was 6.3% initially and 4.5% after ultrasound scan.

Patient Information

Information about the screening was given by midwives at the maternity care centres in the form of a leaflet. It explained the general idea of the screening and the details of the procedure, for example how the test would divide the mothers into two groups. Ninety-five percent of them would fall into a ‘normal group’ with a less than 1/350 risk of DS at birth. They could get the exact risk figure by telephone, if they so wished. The other group, 5% of the mothers, would get the ‘at risk’ result with a higher than 1/350 risk for DS and would be offered additional tests. The mothers’ own choice at all stages was emphasised as well as the fact that the ‘at risk’ result as such did not mean that the child to be bora would definitely have some abnormality. The leaflet contained information on the reliability of the test, indicating that 2 out of 3 cases of DS, 4/5 cases of neural tube defects, and probably all cases of congenital nephrosis of the Finnish type could be detected. Finally, it included the telephone number of our department, where the mothers could get more information from our midwives if necessary. Copies of the leaflet are available from us on request.

Screening Procedure

The serum sample was taken at the local health care centre laboratory 15–16 weeks after the last menstrual period. Usually no ultrasound scan was performed before, because screening by ultrasound was scheduled at 18 weeks in the areas concerned.

Test Results

The negative screening results were mailed to the mothers informing them that the result was ‘normal’ (referring to the leaflet), with no indication for further examinations. In addition, our telephone number was given again, in the case the exact risk figure for DS or more information about the test was required.

In case of a positive screening result, the mother was contacted by one of our midwives by phone. She explained the test result and offered ultrasound scan to confirm the timing of the pregnancy, and AC or CVS if still indicated after the ultrasound. If the offer was accepted, an outpatient visit to our department was arranged for the couples, usually for the next or sometimes even the same day. The visit commenced with a counselling session with a midwife. In cases of high AFP, the counselling was done by a medical geneticist. The meaning of the test results and the differences between AC and CVS were explained to the couple. Ultrasound and AC or CVS were performed according to the mothers’ wishes.

The normal AC or CVS results were mailed to the mother, but she could also make inquiries by phone. The midwives telephoned the mothers who had abnormal results and arranged a counselling session with a medical geneticist.

Opinion Survey

All those who had positive screening results got a questionnaire (A) (App. 1) to complete during the visit. It posed questions about the information available about the test, the couple’s knowledge of Down’s syndrome, their opinions on the necessity of prenatal tests, the couple’s feelings about positive screening results, decision-making processes during the entire procedure and their opinions concerning the reliability of the result of the chromosome study and the rapidity with which the results were forwarded to them. Personal remarks concerning disadvantages and deficiencies noted in the screening procedure and suggestions for changes and improvements were also requested.

A second questionnaire (B) (App. 2) repeating the questions about the necessity, disadvantages and deficiencies of the screening and requests for changes and improvements was mailed a few months after the visit. The mother was also asked if she, given the possibility to reconsider, would take the test again.

A random sample (300) of those who got a negative screen result received a questionnaire (C) (App. 3) by mail. It was similar to A, but questions about further studies after the positive screening result were omitted. A question asking the mother whether she had had AC at her own expense was included.

Results

There were 17,200 pregnancies during the study period of 2.5 years. The participation rate in serum screening was 84% (of those who did not have AC or CVS on account of advanced age). Sevenhundred and eighty-two mothers, including those who came because of elevated maternal serum AFP, visited our laboratory for further studies. Six hundred and twenty-five (80%) filled in questionnaire A during the visit. Four hundred and ten (52%) of them also returned the second questionnaire B a few months later. Two hundred and forty-five mothers (82%) of the screen negative group returned questionnaire C.

Answers to the same questions in A and C are presented in table 1. The questions concerning the availability of information on maternal serum screening and the mothers’ decision to participate were answered very similarly by the positive and negative screening results group. Interestingly, when the study period was divided into a first and a second half, during the second half about one fifth had known about the screening test already before the first visit to the maternity care centre. The information had been given during a previous pregnancy (31%), by (often pregnant) friends or relatives (40%) or a private doctor (7%). Some had found out about it from papers or journals (11%), or through their profession (10%).

The leaflet was considered easy to understand by most. Some (1.2%) confessed that they had not read the paper or did not remember what was in it. Nobody considered it to be too detailed. In the comments section more detailed information about DS, the basis of the serum screening test and chromosome studies would have been welcomed.

The decision to have the serum test was easy for 94%, whereas the decision to have the chromosome study in the positive screening group was easy only for 73%, difficult for 14%, and 13% were of no opinion. Twenty-two percent of the mothers with positive screening and 30% of the mothers with negative screening had considered having AC or CVS in a private clinic at their own expense. Nine mothers (3.7%) from the negative-screening group actually had. These represented 9% of the 80 answers from the first half and 1% of the 165 answers from the second half of the study period.

Replies to the questions about knowledge of DS (table 1) differed in the positive- and negative-screening groups during the first half of the study period. Forty-eight percent of the group with positive and 36% of the group with negative screening remembered knowing or having met a person with DS. The numbers (44 and 41%, respectively) evened up during the second half of the study period. Of both groups, only 6% during the first and 4% during the second half of the study period answered that they did not know anything about DS.

The mothers who had a positive screening result were also asked about their reactions on being informed about the result of the serum test. Seventy-two percent got frightened, 18% took it as part of normal pregnancy follow-up, 2% doubted the need for further studies and 6% had actually hoped for the possibility of AC or CVS. In addition, 14% gave descriptions of their reactions in their own words (table 2).

For the mothers, the most important thing about AC and CVS was the reliability of the result (79%), 8% appreciated the low risk of danger to the pregnancy, and 7% the speed with which the result was available. The question about other factors that were appreciated was answered by 6%. Nineteen percent of these said that all the above-mentioned factors were important, 15% valued the swiftness of the outpatient visit, and the information and attention given. However, 66% stated that the test itself and the possibility of fetal studies was important.

Most of the mothers initially considered prenatal screening tests to be very or quite useful (table 3). However, 12% of the mothers with positive screening results said that they would not take the test again if they could reconsider, whereas 100% of the mothers with negative screening results would take it again. Those who considered the test harmful often marked it as very or quite useful as well.

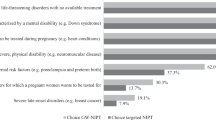

In all questionnaires the participants were asked to mention some disadvantages or deficiencies of the screening, and suggestions for changes and improvements. These comments were found in 18, 58 and 27% of questionnaires A, B and C, respectively (table 4). Too little information about the test, worries and stress, unnecessary in cases of false timing, difficulties in decision-making, and long delays in acquiring the results of the chromosome study were the main complaints. More information at all stages, earlier testing, ultrasound timing before the serum test, and earlier processing of the results were considered to be essential.

Discussion

The screening was well received by the pregnant mothers, 84% of the pregnancies were screened. Ninety-eight percent of the women with positive screening results took an AC/CVS test subsequently. In 10 cases, DS was diagnosed. The couples chose termination of the pregnancy in all of these cases.

The decision to take part in maternal serum screening may be fairly easy. Often a negative screening result seems to be taken for granted, and the positive screening result is unexpected even after adequate information prior to the test. A positive test result causes more alarm than the fact of merely belonging to an ‘at risk’ age group.

The necessity for sufficient information at all stages of the screening cannot be stressed enough [8, 11, 12]. Knowledge of the existence of serum screening spreads very effectively among the population of women planning to have children. During the second half of our study one fifth of the mothers had learned about it before their first visit to the maternity care centre (table 1). The role of friends and relatives was much more prominent than that of doctors or the media.

The leaflet given by the midwife at the beginning of the pregnancy was well received by the mothers (and husbands). It was short enough to be read by most, but consistently the amount of information was not sufficient for all, especially if the result of the serum test was positive. Some mothers suggested the distribution of a second complementary leaflet.

More information is acutely needed when a positive screening result is obtained. Getting a positive screening result by phone from a person who can explain its relevance, arrange further examinations, and answer immediate questions was far superior for the worried mother to getting information by mail. After recovering from the first shock, the counselling by the midwives (often on the following day, before the CVS or AC, with the husband) was experienced as very informative and supportive, as expected [4]. However, it was not sufficient. The role of the obstetrician performing the CVS or AC is important (table 4). It has been noted before that too much routine or hurry was experienced as cold or depressing [13]. Reassurance is required also from the doctor. It helps to cope with a positive screening result during the waiting period for the results of the chromosome analysis.

Even after a false-positive result, 91% considered the test very or quite useful. However, 12% would decide against taking the test if they could reconsider, probably due to the severe stress experienced during the procedure. Thirteen mothers with false-positive results criticized serum screening as being unethical, because it may lead to termination of pregnancy and elimination of the handicapped.

There is a risk that some anxiety about the health of the child remains until the end of the pregnancy [14, 15]. Questions about the meaning of the positive screening result ‘when the chromosomes were normal after all’ may reflect this and the difficulty in understanding the concept of risk due to calculated probabilities [5].

Overall, the serum screening was well received by most mothers, and most coped at all stages. However, it seems inevitable that unexpected psychological problems may be encountered in some cases [9]. These need to be anticipated and dealt with.

In contrast to some reports [10, 16], our experience was that, the personnel in maternity care were almost without exception in favour of the screening. Despite the introductory training given, a lack of knowledge at the local maternity care centres was noted by the mothers. However, the direct contact with our department by phone probably helped in acquiring more information and correcting any mistakes. The midwife at the maternity care centre and a nurse at the laboratory drawing the blood samples were the two local contact persons involved in the screening. In our department, these contact persons were the midwives and the obstetrician performing AC or CVS. Counselling in cases of high maternal serum AFP, and abnormalities in fetal ultrasound, amniotic fluid or chorionic villi was done by a medical geneticist. We feel that too many people communicating between the pregnant mother and the unit performing the screening may confuse and cause unnecessary misunderstandings.

References

Salonen R, Simola K, Harjulehto-Mervaala T, Aro T, Saxen L: Incidence of Down syndrome and prenatal diagnosis during the years 1984–1988 in Finland. Duodecim 1993;109:681–686

Wald NJ, Cuckle HS, Densem JW, Nachanal K, Royston P, Chard T, Haddow JE, Knight GJ, Palomaki GE, Canick JA: Maternal serum screening for Down’s syndrome in early pregnancy. BMJ 1988;297:883–887

Abuelo DN, Hopmann MR, Barsel-Bowers G, Goldstein A: Anxiety in women with low maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening results. Prenat Diagn 1991;11:381–385

Keenan KL, Basso D, Goldkrand, J, Butler WJ: Low level of maternal serum α-fetoprotein: Its associated anxiety and the effects of genetic counselling. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:54–56

Roelofsen EEC, Kamerbeek LI, Tymstra TJ, Beekhuis JR, Mantingh A: Women’s opinions on the offer and use of maternal serum screening. Prenat Diagn 1993;13:741–747

Beekhuis JR, De Wolf BTHM, Mantingh A, Heringa MP: The influence of serum screening on the amnio-centesis rate in women of advanced maternal age. Prenat Diagn 1994;14:199–202

Marteau TM, Johnston M, Shaw RW, Slack J: Factors influencing the uptake of screening for open neural-tube defects and amniocentesis to test for Down’s syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1989;96:739–741

Smith DK, Shaw RW, Marteau TM: Informed consent to undergo serum screening for Down’s syndrome: The gap between policy and practice. BMJ 1994;309:776.

Statham H, Green J: Serum screening for Down’s syndrome: Some women’s experiences. BMJ 1993;307:174:176.

Khalid I, Price SM, Barrow M: The attitudes of midwives to maternal serum screening for Down’s syndrome. Public Health 1994;108:131–136

Green JM: Serum screening for Down’s syndrome: Experiences of obstetricians in England and Wales. BMJ 1994;309:769–772

Vyas S: Screening for Down’s syndrome: Ignorance abounds. BMJ 1994;309:753–754

Green JM: Prenatal screening and diagnosis: Some psychological and social issues. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:1074–1076

Marteau TM, Cook R, Kidd J, Michie S, Johnston M, Slack J, Shaw RW: The psychological effects of false-positive results in prenatal screening for fetal abnormality: A prospective study. Prenat Diagn 1992;12:205–214

Marteau TM, Kidd J, Cook R, Johnston M, Michie S, Shaw RW, Slack J: Screening for Down’s syndrome. BMJ 1988;297:1469.

Marteau TM, Slack J, Kidd J, Shaw RW: Presenting a routine screening test in antenatal care: Practice observed. Public Health 1992;106:131–141

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1

Questionnaire A

Dear participant,

We wish that you would kindly answer the following questions either by marking the alternative most appropriate for you or in your own words.

-

1

How did you learn about serum screening?

-

□ at the maternity care centre during this pregnancy

-

□ earlier how? ____

-

-

2

Did you get the information leaflet? yes □ no □

If you did, was it

-

□ difficult to understand

-

□ easy to understand

-

□ too general

-

□ too detailed

-

□ something else, what? ____

-

-

3

Are these screening tests during pregnancy

-

□ very useful

-

□ quite useful

-

□ rather useless

-

□ quite useless

-

□ harmful

-

□ I cannot tell

-

-

4

Did you find deciding about the blood test

-

□ easy

-

□ difficult

-

□ I cannot tell

-

-

5

Are you familiar with Down’s syndrome or mongolism?

-

□ I have met a person with it

-

□ I know the symptoms well

-

□ I know the main symptoms

-

□ I have no idea of Down’s syndrome

-

-

6

How did you take the offer of further studies

-

□ I got frightened

-

□ I had wished for it

-

□ I doubted the need for them

-

□ as part of normal pregnancy follow-up

-

□ otherwise, how? ____

-

-

7

Did you find deciding about having amniocentesis or chorionic villi sampling done

-

□ easy

-

□ difficult

-

□ I cannot tell

-

-

8

Had you considered amniocentesis or chorionic villi sampling at your own expense in a private laboratory?

-

□ not at all

-

□ yes, a little

-

□ yes, seriously

-

-

9

What do you appreciate most in the further examinations?

-

□ the reliability of the results

-

□ the low risk of danger to the pregnancy

-

□ the speed with which the result is available

-

□ something else, what? _____

-

Please fill in the following spaces, if you can mention

-

1

Disadvantages or deficiencies that you have noticed in serum screening:

-

2

Suggestions for changes or improvements:

Thank you for your help!

We will send you another questionnaire by mail, in three months time to see if your opinions with regard to serum screening have changed after some time has passed.

Appendix 2

Questionnaire B

Dear participant in maternal serum screening study,

We are still bothering you with this additional questionnaire, would you please mark again the alternative most appropriate for you or explain in your own words.

-

1

Thinking back, was serum screening and the further examinations following it to you

-

□ very useful

-

□ quite useful

-

□ useless

-

□ harmful

-

□ I cannot tell

-

-

2

If you reconsidered participating in maternal serum screening, would you still do it? yes □ no □

-

3

How about generally, are this kind of screening studies during pregnancy

-

□ very necessary

-

□ quite necessary

-

□ rather unnecessary

-

□ quite unnecessary

-

□ harmful

-

□ I cannot tell

-

Please fill in the following spaces, if you now can mention

-

1

Disadvantages or deficiencies that you have noticed in serum screening:

-

2

Suggestions for changes or improvements:

Please return the questionnaire to the Laboratory of Prenatal Genetics in the enclosed pre-paid envelope.

Thank you for your help!

Appendix 3

Questionnaire C

Dear expectant mother participating in maternal serum screening study,

The study is new and still developing and we would like to know what expectant mothers think about it. Thus we wish that you would kindly answer the following questions either by marking the alternative most appropriate for you or in your own words.

-

1

How did you learn about serum screening?

-

□ at the maternity care centre during this pregnancy

-

□ earlier how? ____

-

-

2

Did you get the information leaflet? yes □ no □

If you did, was it

-

□ difficult to understand

-

□ easy to understand

-

□ too general

-

□ too detailed

-

□ something else, what? ____

-

-

3

Are these screening tests during pregnancy

-

□ very useful

-

□ quite useful

-

□ rather useless

-

□ quite useless

-

□ harmful

-

□ I cannot tell

-

-

4

Did you find deciding about the blood test

-

□ easy

-

□ difficult

-

□ I cannot tell

-

-

5

Are you familiar with Down’s syndrome or mongolism?

-

□ I have met a person with it

-

□ I know the symptoms well

-

□ I know the main symptoms

-

□ I have no idea of Down’s syndrome

-

-

6

Had you considered amniocentesis or chorionic villi sampling at your own expense in a private clinic?

-

□ not at all

-

□ yes, a little

-

□ yes, seriously

-

-

7

Did you have amniocentesis or chorionic villi sampling at your own expense in a private clinic?

-

□ no, I did not

-

□ yes, I did; was the result normal □ abnormal □

-

-

8

If you reconsidered participating in maternal serum screening, would you still do it? yes □ no □

Please fill in the following spaces, if you can mention

-

1

Disadvantages or deficiencies that you have noticed in serum screening:

-

2

Suggestions for changes or improvements:

Please return the questionnaire to the Laboratory of Prenatal Genetics in the enclosed pre-aid envelope.

Thank you for your help!

Riitta Salonen, MD

Laboratory of Prenatal Genetics

Tel. 471 3605

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salonen, R., Kurki, L. & Lappalainen, M. Experiences of Mothers Participating in Maternal Serum Screening for Down’s Syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 4, 113–119 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1159/000472180

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1159/000472180

Key Words

This article is cited by

-

Maternal serum screening for Down's syndrome

Public Health (1997)