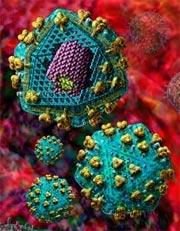

Retroviruses, of which HIV is a modern example, infiltrated our genome long ago.RUSSELL KIGHTLEY / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Retroviruses, of which HIV is a modern example, infiltrated our genome long ago.RUSSELL KIGHTLEY / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYResearchers in France have recreated a 5-million-year-old virus whose remains are now found littered across the human genome. The ancient virus could help us to understand how these genetic remnants contribute to cancer.

The virus is of a type called a retrovirus, which can insert copies of its genetic material into our own DNA. These viruses probably infected eggs and sperm of our primate ancestors many millions of years ago, and pasted numerous copies of their genetic material into the genome. The relics of these copies in human DNA are called human endogenous retroviruses, or HERVs.

Today, copies of HERVs make up some 8% of our genetic code. But these copies have racked up mutations and are largely obsolete: scientists have never found one that can still convert itself into new, infectious virus particles.

Now Thierry Heidmann at the Gustav Roussy Institute in Villejuif and his colleagues, have brought one of these retroviruses back to life. They call it Phoenix, for the mythical bird reborn from its own ashes.

"It's a Jurassic Park kind of experiment to resurrect an old virus," says John Coffin who studies retroviruses at Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts. "It's just kind of cool."

Rising from the ashes

Heidmann's team focused on a particular type of retrovirus that infected human cells less than 5 million years ago and left a legacy of some 30 copies of itself in the modern human genome. These duplicates have all become slightly different over time as they acquired various mutations. By comparing them, the researchers worked out the most likely sequence of the original virus from which they were copied.

“It's a Jurassic Park kind of experiment to resurrect an old virus”

John Coffin,

Tufts University.

The team then used the DNA of two existing HERVs as a backbone and engineered specific mutations into it, to build a duplicate of the original Pheonix. They inserted it into human cells to see what it would do.

The ancestral virus was able to copy itself and manufacture new virus particles, they found. And these particles could infect fresh cells and copy and paste its genes into these cells' genome.

The study suggests that cells acquired numerous copies of this ancestral retrovirus by the same cyclical process: the retrovirus manufactured new particles that escaped one cell and infected eggs and sperm again and again. This may have still been happening just a few hundred thousand years ago.

Dangerous infection

The team also found hints that some of the HERVs in our genomes might still be infectious. They spliced together parts of three HERVs — a process that could occur spontaneously in a cell — and found that they could also produce infectious viruses. Heidmann says that the human genome may even harbour as-yet undiscovered HERVs that are naturally infectious.

The ancient virus might help us understand whether and how retroviruses contribute to cancer, Coffin says. Researchers have found that cells of certain tumours contain retroviral proteins or whole viruses, as if a HERV has reactivated. Armed with the active virus, they'll be able to test whether infection actually accelerates the disease.

The resurrection of an ancient, infectious virus is also likely to raise concerns, which Heidmann acknowledges. Last year, resurrection of the 1918 pandemic flu virus prompted fears about the virus's escape (see 'The 1918 flu virus is resurrected').

ADVERTISEMENT

Heidmann points out that the retrovirus is around 1,000 times less infectious than the famous HIV retrovirus. The group also engineered the virus so that it can only copy itself once and cannot proliferate out of control. "It's not impossible that it could turn out to be a pathogen but I think it's very unlikely," agrees Coffin.

Visit our humanvirus_resurrecte.html">newsblog to read and post comments about this story.

Tufts University.